Adapted from Monsters: The 1985 Chicago Bears and the Wild Heart of Football (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), available now.

Of all the Bears I spent time with, my favorite was Doug Plank. He was off the roster by '85 yet remained the spirit of the team, the personification of the vicious, hard-hitting 46, the defensive scheme that defined the Bears in the 1980s. We met in Scottsdale, where Plank has lived for the last several years. In his playing days, he was a shade under six feet, a biscuit under 200, a quick, mean safety who roamed all over the field. His hair was surfer blond, his eyes a glazed, happy blue. Every player has a Doug Plank story. He was a maniac. From first play to last, his career was defined by big hits. "I remember his final game," wrote Steve McMichael, a defensive end who embodied the Bear's chaotic spirit. "A big old behemoth pulling guard … came around. Here goes Doug, forcing the play. He came up, the guy didn't try to cut him, so Doug took him on high. Doug took his ass out—boom, hit him as hard as he could. It laid out the guard, but it pinched both nerves on both sides of [Doug's] neck so badly that all he could do was stand there."

"Nah, that's not what happened," Plank told me. "It was a short pass, a curl. I was coming from my safety position cause the pass was only 10 yards. I was breaking on the ball and didn't realize that another one of our players was coming just as hard from the other side. Otis Wilson. As I was getting ready to put my helmet into the receiver, he fell down. At the last second—I don't even know if I really remember this—I saw a flash of Otis coming full speed. We went head first. Next thing I know, I was on all fours with something dripping from my face. My helmet had come down and opened my nose. It was busted, blood pouring out. And next to me is Otis on his back, eyes wide open, staring into oblivion, out cold."

"It was in Detroit," Wilson said. "I had the receiver and Doug—he don't see the ball. He just see the man, torpedoes himself right into people. And he got me. I'm coming this way and he's coming that way. I'm 245, he's 196—so he ain't gonna win. I was pissed off at that son-of-a-bitch. Open your eyes! He was a great guy but he'd knock the shit out of you."

"It was a spinal concussion," Plank told me. "About the only thing I can compare it to is sticking your finger in a socket. I stuck my finger in plenty of sockets when I was a kid so I know what I'm talking about. That was happening in the lower half of my body. Numb. Pins and needles. That feeling in my left leg, it never went away."

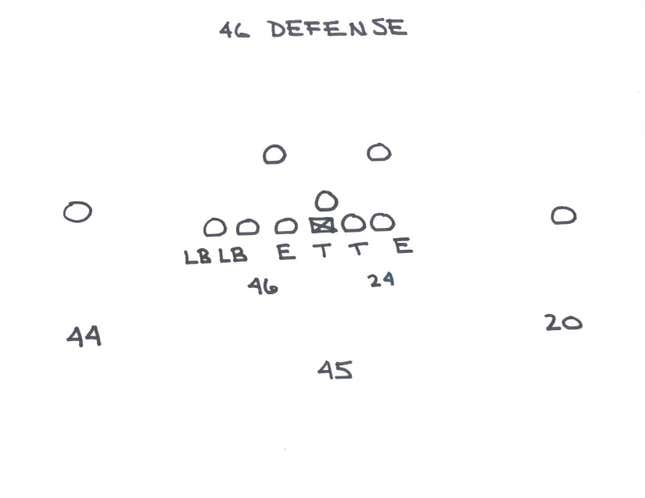

It was Plank who gave the defense its name: the 46. Many fans assume it came from the on-field alignment of players, as with the 3-4 defense and the Cover-2. In fact, 46 means nothing more than we're coming hard, in the way of the man who wears that number, Doug Plank.

The defense was a puzzle, a blizzard of reads and options, but, when I spoke to Plank, he summed it up like this: "We're going to get to know your backup quarterback today."

Plank has slimmed down since his playing days, but is still blonde, tough, handsome, and cool. He's the sort of older kid you meet at camp and follow around all summer. He's not gotten away as clean as some—he's had his knees replaced, and has titanium shoulders. The aftereffects of life as a missile. When I asked what caused the damage, he said, "Every body has a certain amount of hits in it. Mine had 237. Unfortunately, I took 352."

Even when the Bears were bad, there was Payton on offense and Plank on defense. A late hitter? A dirty player? "Well, yeah, you'd look at it and say, 'Gosh, Plank came late and took that guy's head off.' But all I was doing was flying over the pile; what looked like a big collision was just me sailing by. One time, I remember going back and saying to the ref, 'But I didn't even hit the guy.' And he said, 'Maybe not, but you had bad intentions.' And you know what? He was right. I had bad intentions from the moment I walked on a football field."

Plank was one of the only players to ever knock the great power running back Earl Campbell out of a game. "We watched film of the Broncos' safety Steve Foley trying to tackle Earl," Plank told me. "Generally, with film, you see everyone on the line, then the action, then it cuts to the next play. In this case, we saw Earl break through the line and Foley come to make the tackle. He put his helmet into one of Earl's thighs. But his thigh pads were 34 inches. Mammoth. Think about it. I had a 29-inch waist. Foley got knocked back, then knocked out. Instead of cutting to the next play, the film stayed on the scene as a crew of medics carried Foley away on a stretcher. Buddy [Ryan] turned off the camera and said, 'If any of you guys don't want to play this weekend, let me know.' So I sat there, thinking: 'You know what? I'm not going to hit Earl Campbell in the legs.' He wore metal thigh pads, not the foam rubber type like in Pop Warner. When Earl hit you, it sounded like an aluminum baseball bat: Doinggg, doinggg. So I thought, 'Where is Earl Campbell vulnerable?' Yes, yes, between the legs. So that whole game, I was waiting for the moment I could drive my helmet into the vulnerable area. When I finally got the chance, I put him down."

Plank numbers his own concussions, from dings to who-am-I-and-why-am-I-here blasts, in double digits. He carried smelling salts in his waistband to bring himself around. After an especially big hit, he would shake his head, then look at his uniform. "If it was the dark one, I'd tell myself, 'Go stand with the guys in the dark jerseys.'" He knew the protocol, how to keep himself in a game. "You'd run to the sideline and the doctor would hold up his fingers, how many, how many, but it was always two."

Judged by today's standards, Plank told me his entire career would be considered a penalty, an endless whistle blowing in the canyons of hell. "What's football?" he asked. "It's chess. Tackle chess. And what's the quarterback? He's the king. Take him out, you win the game. So that was our philosophy. We're going to hit that quarterback 10 times. We do that, he's gone. I hit him late? Fine. Penalize me. But it's like in those courtroom movies, when the lawyer says the wrong thing and the judge tells the jury to disregard it, but you can't un-hear and the quarterback can't be un-hit."

Plank wishes every fan could cover an opening kickoff in the NFL, just for the excitement, the rush of running down field with the noise and the color and the scoreboard and the big hit waiting as a beer waits at the end of a long day. Doug Plank represented the regular man, which is why he was so beloved by fans. He was a good high school player, but neither big nor fast enough to attract division one scouts. So he scouted himself, writing up his games at his desk in Pennsylvania, sending these reports to Joe Paterno, the coach of Penn State, where Plank had always dreamed of playing.

The day after his last high school game, Doug was shooting baskets in the gym when Paterno walked in: glasses, blue windbreaker. He called Doug over, then turned to the gym teacher and said, "Coach, OK if we use your office?" Paterno sat Doug down, then broke his heart, returning the letters, complimenting his spirit but telling him he was too small to play big time college football. He offered to write letters of introduction to division three schools.

A few weeks later, Doug was called to the principal's office, where Woody Hayes, the Ohio State coach, was waiting. He said, "Doug, how'd you like a full scholarship to play football for me?"

"It's what I've dreamed of all my life," Plank told him.

Sophomore year, an assistant coach asked Plank, who rarely started at Ohio State, if he ever wondered why he'd gotten that scholarship.

"Yeah, sort of."

"'Cause Woody heard Paterno had been to see you and wanted to screw him up."

After Plank's rookie NFL season, in which he lead the Bears in tackles, Paterno began invoking the story as a cautionary tale. "Keep an open mind," he'd tell his scouts, "one of the little guys might be another Doug Plank."

It was a fluke that brought Plank to the Bears, who took him, for sentimental reasons, in the 12th round, which is like not being drafted. "That's why I played the way I did," he told me. "The good players, the guys with talent, they have an A game, a B game, a C game. They don't feel perfect, it's practice, OK, go with the B game. I didn't have that option. There was only the A game for me—as hard as I could every time or I would not be on the field; that's what gave me such intensity."

"He used to take guys out in practice," McMichael wrote. "I guess that's why our offense stunk back then, nobody was going to catch a pass over the middle. [Doug] used to hit guys so hard he'd knock himself out."

"He cold-cocked me in practice," said wide receiver Brian Baschnagel. "We were just in helmets, no pads. Inside. On a gym floor. I went across the middle, and he nailed me. As he helped me up, he said, 'Oh, Brian, I'm sorry. I didn't know that was you.' Then, 10 minutes later, he does the same thing. This time, as he helps me up, he says, 'That time I did know it was you, Brian.'"

When I asked Plank what makes someone a hitter, he thought a moment, then said, "Try running into a wall. A normal person will slow down at the last moment—a hitter will accelerate. When people say I was great in my day, I say, No, I was just able to control my mind for those few seconds before impact. I never slowed down. I sped up. That's what makes a hitter. Not size, not speed. It's the ability to suppress your survival instincts. We've all known big physical players that just don't want to hit. We've seen people that you look at and go, no way, but they put a uniform on and become a terror. If you can convince yourself that what you're doing on that field is not going to hurt you, you'll be capable of anything. It takes practice. You have to develop the mental capacity to keep moving those legs even when you know pain is coming."

"When I played, I played angry," he added. "It sounds childish, but I would trick my mind into believing that the person on the other side had done something to me or my family and now it was time to deliver justice. It sounds shallow, but you have to work yourself up into a fury. I never went to the Super Bowl. I never played in a Pro Bowl. But here's one thing I did do: hit as hard as I possibly could every time I possibly could."

To me, Doug Plank was a revelation. Not only because he was smart and funny but because he has considered and reconsidered every moment of his career. He's thoughtful. What's more, he typifies the Bears' mentality. "You get to Chicago and you look around and see all the incredible history," he told me. "Halas, Butkus, the defenses, the Hall of Famers, and you feel like you have an obligation. When I first got there, people told me, 'Doug, win or lose, you'd better be tough and physical, you better play like a Bear.' I remember my mindset going out on to the fields in those first years: If we were not going to beat the other team, we were at least going to beat them up." He was a throwback, a perfect example of an old time player; in him, you recognized the energy and gleeful anger that made football the national game. What is baseball when you can watch Doug Plank seek frontier justice on a Sunday afternoon? He could have played with Jim Thorpe, or Red Grange, or Bronko Nagurski—he could still be playing today. He's the foot soldier, the cannon fodder, the grunt, the sort of player who has lit the boards from the beginning. It was hard hitters from the grim coal towns that made the game worth watching. In Doug Plank, you see the spirit and history of the Chicago Bears, and the game itself.

I sometimes wonder about the legacy of big hits—not just the damage it does to the body and brain but the way it affects the psyche. Once, in a high school hockey game, I was caught behind the net with my head down and a kid named Oscar hit me so hard it did not even hurt. I found myself a few seconds later sitting ten feet from the puck, thinking about a spider web I had seen the previous summer in Eagle River, Wis. I was in a daze and I stayed that way for a week. I kept playing hockey but never again played the same way. I had realized that I could break.

"I recently had the opportunity to meet a player that I forced out of the National Football League," Plank said one afternoon as we drank coffee beneath an acacia tree. "And I have to tell you, it isn't a good memory. This was a receiver running a deep end route, a dig route—he dashes 15 or 20 yards down the field, and crosses the middle. I remember this once—don't ask me why—I made a decision to hit him low. I tore his cartilage—his ACL, his MCL. It was over for him in an instant. He lay on the ground in agonizing pain. And I could hear this groan—it came from the deepest part of his person. I remember not feeling good about that. Then, about two months ago, I ran into that person. Here, in town. It was so hard. It would have been easy to duck in a corner. I knew he was there. But I thought, You know what? I want him to know how I felt that day. I never hit a person low again. If I hit a guy from waist up, OK, they might get a hip-pointer, break a rib, get knocked out. But they're coming back. You're not tearing up their career. I walked over to him and said, 'I want to tell you how sorry I am.' Well, I got to tell you, two grown men broke out in tears right there. He goes, 'You don't know how much I thought about you over the years, wondered who you were, what kind of person, and why you do this to me.' And I told him I felt the same way and often thought of him. It's not one-sided. You do something, you walk away and forget it. It's not like that. You live with these things for a very long time."

Rich Cohen, a New York Times bestselling author, grew up on the North Shore of Chicago, where he died with the Cubs and was reborn with the Bears. He has written 10 books and a host of magazine articles for, among other things, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper's Magazine, and Vanity Fair, where he's a contributing editor. Cohen has won the Great Lakes Book Award and the Chicago Public Library's 21st Century Award, and his essays have been included in The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing. He lives in Connecticut with his wife and three sons, but is plotting his return to Chicagoland.

Monsters: The 1985 Chicago Bears and the Wild Heart of Football is available on Amazon. Top image by Jim Cooke.