ESPN's earliest days—as documented by Bill Rasmussen's Sports Junkies Rejoice; Michael Freeman's ESPN: An Uncensored History, and James Miller and Tom Shales's Those Guys Have all the Fun—are usually viewed as part of a generally accepted narrative. It goes something like this: The charismatic and recently fired New England Whalers communications director Bill Rasmussen, with some help from his similarly exuberant 22-year-old son Scott, had an inspired and unprecedented vision for a cable network devoted entirely to sports. They first planned to focus entirely on the Connecticut region, that seething hotbed of sporting action that included the pre-Auriemma/Calhoun era University of Connecticut, the short-lived World Hockey Association's Whalers, and the AA Bristol Red Sox.

The Rasmussens quickly realized that it would cost about the same amount to distribute their content nationally via satellite. They secured funding from the Getty Oil Company, struck a deal with NCAA czar Walter Byers, compelled Anheuser-Busch to sign the largest-ever contract in cable TV history, recruited NBC producer Chet Simmons, and voila!—the birth of a cable network that Forbes would eventually name the world's most valuable media outlet.

But there's another name from ESPN's pre-history that's gone virtually unnoticed. When doing some research for a book I'm now writing called ESPN Culture—which will take a look at how the "Worldwide Leader" builds credibility and authority in different media and cultural settings—I came across Bob Beyus's name a few times. Beyus, a telecommunications engineer by trade, started the Cable Promotions Company with insurance agent Ed Eagan in early 1978. They were developing a sports magazine program for syndication to regional cable outlets and took a meeting with the Rasmussens to gauge the Whalers' potential interest in the show. Beyus and Eagan rightly thought Bill's flair for sales and his industry contacts would come in handy. Shortly after that first meeting, the Rasmussens joined forces with Beyus and Eagan to start what they initially called the E.S.P. Network. It is at this point that Beyus's name disappears from popular records of ESPN's history. The Rasmussens claim he was discouraged by the initially tepid reception E.S.P. received from potential clients and bailed. Their account seems reasonable enough, but I found it curious that none of the ESPN books included Beyus's voice and figured I'd give him a buzz. A few weeks later I received a message from a grandfatherly man who claims he "agonized" over whether to return my call. He caught me off guard given that my intention was not to uncover anything, but simply to gather some basic facts about the days before ESPN's every move was newsworthy.

Though friendly and soft-spoken, Beyus brashly claimed to be the "father of ESPN" and to "own its birthright." He also argued that Eagan and the Rasmussens "conned" him. He said that he bankrolled the endeavor's initial operations—from phone bills to office supplies—and that he was "squeezed out" by partners who considered him a mere placeholder while they were sniffing around for someone with deeper pockets and better technological resources. Beyus left, he said, primarily because he was running out of cash and his partners were bleeding him dry. He claimed he wound up losing his home as a result of his investment in E.S.P. When asked why he had never pursued legal action, he said he worried that ESPN parent Getty Oil would have kept any lawyer he retained tied up in court until his resources ran dry. When asked why he decided to tell me this story after more than three decades, he simply said he thought it was time for his perspective to be made public.

Beyus's tale is not the only new counter-history circulating about ESPN. Bill Rasmussen's estranged brother Don—who invested $10,000 in the project and worked for the company until 1980—recently self-published the humble-braggingly titled Just a Guy: An Autobiography of the Quiet Founder of ESPN, which asserts his apparent centrality to the company's history. I told Beyus he could likely do the same and make a few bucks, but he said he wasn't interested. "There was never any offer to reimburse me for my expenses with E.S.P.," he wrote me recently. "I never signed away my rights to that corporation. It is my hope that someone still has a conscience and will do what is right."

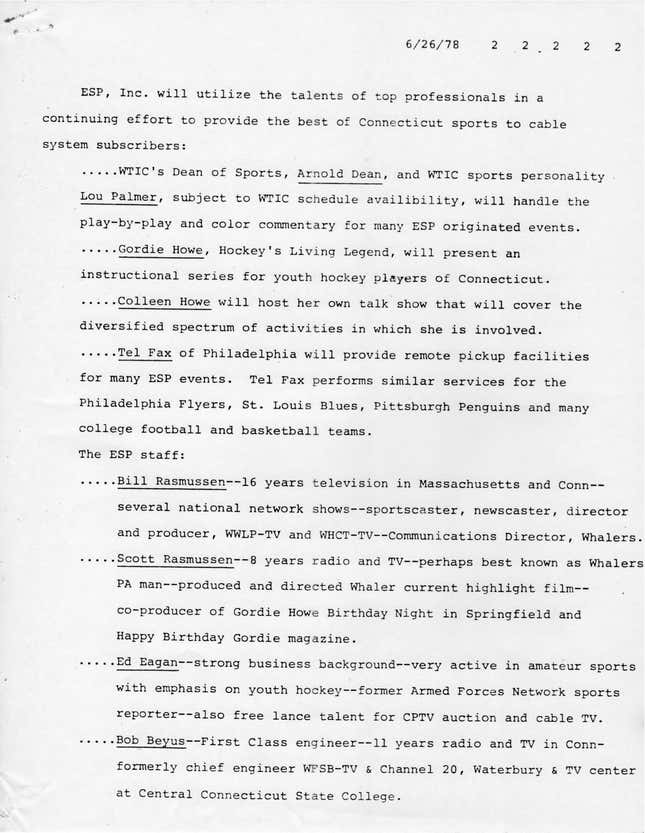

Beyus shared a copy of E.S.P.'s first press release with me. It seems to be the first company document in ESPN history. It's never been seen before, as nearly as I can tell. I'm no lawyer, but the document doesn't seem to prove that Beyus was conned. Really, it's just a historical curiosity that has been filed away since the late 1970s along with the aging New Englander's boxes of yellowing tax records and utility bills. This has tremendous value for those of us who care about sports history and realize the importance of ESPN to that heritage. What's more, it suggests that ESPN's pre-history is messier than we know, and that Beyus's place in that history likely warrants more than a mere footnote.

I've annotated the document down below. Click on a number below each page to highlight an annotation.

Travis Vogan teaches Journalism and American Studies at the University of Iowa. His first book, Keepers of the Flame: NFL Films and the Rise of Sports Media, will be published by University of Illinois Press in March 2014. He is currently working on a book titled ESPN Culture.

Art by Jim Cooke