It's been nine years since police in Fairfax County, Va., turned small-time bettor Sal Culosi into a bookie and then killed him, but Culosi's death has been forcibly dragged back into the news, and so has all the unaccountable power-drunkenness that led to it. His killers, we've been reminded, struck again.

Culosi's father, Sal Sr., wrote about the killing of his son in an op-ed that appeared in the Washington Post on Christmas Eve. His piece asked for justice for John Geer, another unarmed man killed by the same force that wrecked his family, and whose case has caused a revisiting of the younger Culosi's death. "I hope that the court in the Geer case resists its traditional inclination of favoring the government," the elder Culosi wrote.

In other words, he wants Geer to get more justice than his son ever did.

Culosi was unarmed and standing in his socks in front of his townhouse on Jan. 24, 2006, when a member of the Fairfax police tactical squad, or SWAT team, gunned him down. The shooter, Officer Deval Bullock, had shown up with other cops seconds before to serve a search warrant to look for evidence of football betting just days before Super Bowl XL.

Bullock's version of why and how he killed Culosi changed over time. A year after the killing, though, the county released a report stating that the shooting was due to a "reflex-like involuntary muscle contraction" in Bullock's right hand, one caused by his car door bumping his left side. The official excuse holds that Bullock's finger was, against department policy, on the trigger of his Heckler & Koch USP semi-automatic pistol and pointing center-mass at Culosi when that contraction occurred, so that a .45 bullet was fired into Culosi's chest. The family never bought that story, and even produced animated recreations of the shooting that they claim show Bullock's version was physically impossible.

The county's report asserted that the use of a SWAT team "was based on a potential nexus between illegal gambling and the propensity for weapons," and that deploying the squad to make an arrest is "intrinsically safer than most other tactics."

That doesn't wash with Culosi's loved ones, either. Cabi Smith, a close friend of Culosi's, says they were part of a circle that met regularly at Fast Eddie's, a Northern Virginia pool hall, beginning in the 1980s. Smith says through the years the barflies bet on everything: pool, cards, darts, and even flip-cup, which is normally just a drinking game.

"It was the pool hall mentality," he says, "where unless there's some money on it, a little sting, there's no interest. The whole idea that a SWAT team would swoop in for that, that they'd frame Sal and turn him into a bookie, well, that's the story."

After a member of the circle got in trouble with management at Fast Eddie's, much of the gang became regulars at the now-closed Thursday's Sports Bar in Gainesville, Va. It was there, in the fall of 2005, that Culosi met David Baucom, an undercover agent who was detailed to the county's money laundering unit and who was working gambling cases at the time.

It's hard for any Virginia official to make an anti-gambling argument on any sort of moral grounds. In 2008, the Virginia Lottery, an independent agency of the state government, spent $26 million marketing its games, including an $840,000 payment to license Howie Mandel's image and "Deal or No Deal" name for a scratch ticket. The state netted $538.6 million in lottery profits for 2014. But the Culosi investigation came during the poker boom, and the detailing of an undercover detective to local sports bars was but one sign that Fairfax police were on a crackdown of non-state-sponsored gambling. A month before Culosi was killed, they raided a poker game at a Great Falls home while decked out in what one source familiar with the event described as "helmets and body armor and automatic weapons and the whole bit." All gambling charges against the homeowner, an occasional poker pro, were eventually dismissed. A month after Culosi's death, "more than 100" officers raided eight locations in Fairfax in one day, going after alleged sports betting operations.

Smith thinks that Baucom homed in on Culosi because he had more money than everybody else in the clique. But, Smith says, all that money came from Culosi's day job—owning and operating optometry clinics—and not from wagering. Not long after Culosi was killed, Smith told me he'd never seen Culosi bet more than $50 on a football game. "I know what big gambling is," he said, "and if you're not laying off bets [with other bookmakers], it's not a business. Sal wasn't laying off any bets."

The county alleged that Baucom placed bets totaling "approximately $28,000" with Culosi over the 2005 football season, and lost about $5,000 on the year. The police never presented any evidence that anybody but undercover cops was betting with Culosi, but the lawmen alleged there was at least one day where Baucom had wagered $2,000, enough for Culosi to meet the state's legal definition for a bookmaker. And enough, apparently, to call in the SWAT team to take him down.

After Culosi was killed, according to the family, Baucom took Culosi's cellphone and began calling random numbers in it, trying to find others who'd say they'd used the dead guy as a bookie. (They ended up reaching relatives.) This wasn't exactly a sign that the authorities had a strong case against the man they'd just killed.

"My son wasn't a kingpin, thank you very much," says Anita Culosi, Sal's mother. "He was an optometrist."

County officials clammed up while Sal Culosi's body was still warm. Commonwealth attorney Robert Horan, who in his 40-year career as a prosecutor never indicted a single police officer for a shooting, quickly declared that he would file no charges against his shooter, and refused to put the case before a grand jury. The Culosis made requests to Horan, to the police department, and to the board of supervisors for information about their son's killing, but they went largely unanswered; the county wouldn't even disclose the name of his killer for a year. The parents filed a wrongful death lawsuit in 2007, seeking $12 million.

"Unless you sue they won't say anything," says Anita Culosi.

Now the county is facing another $12 million lawsuit for another killing of an unarmed man. John Geer was gunned down in the doorway of his home in August 2013 as his family and friends looked on. Images show him with his hands empty and held above his head just before he was shot. Police waited for more than an hour to move in as Geer lay behind the door, bleeding to death.

Jeff Stewart, who calls Geer his best friend, says they were supposed to go golfing the day of the killing. Geer's wife called police after a domestic dispute, and Stewart showed up after the standoff was already underway. Eventually, Stewart would see helicopters and tanks and lots and lots of men in full combat regalia scrambling all over Geer's property in broad daylight. He says he watched for 40 minutes as three Fairfax officers stood 20 feet away from Geer, talking to his buddy with their guns constantly pointed at him. "I saw John's hands slowly starting to come down, and I thought maybe he was coming out," says Stewart. "And when his hands came to about face level, one of the cops shot him."

Stewart could only say "one of the cops" because he, like the Geer family, didn't know the actual identity of the killer until this week—17 months since the killing. The county had, previously, released basically no information about the case. (By way of disclosure, I grew up in Fairfax County and have friends whose kids played on and against girls' travel softball teams that Geer coached.)

The police in Fairfax County have earned a reputation for stalling after unarmed men die at their hand. Sometimes that strategy pays off, as it did after the killing of David Masters, who was shot from behind while sitting in the driver's seat of his car in November 2009. He'd been stopped on suspicion of stealing decorative flowers from a planter outside a local store. The police department eventually said that Masters had made a "furtive gesture" that forced the officer to shoot him twice from behind. No weapons were found in his automobile. In a piece in the Washington Post announcing that Fairfax police had cleared the officer of wrongdoing, Fairfax County Commonwealth's Attorney Raymond F. Morrogh said the cop thought he was dealling with a car thief, not a flower stealer. Morrogh also told the paper that Masters "was not shot in the back."

"He was shot in the damn back," says Barrie Masters, the victim's father. "He was in his own damn car with his puppies. They lie a lot."

It was a curious denial, since the photo accompanying the story showed the rear passenger window was blown out by the fatal shots and the autopsy report—we've posted it online, if you're interested—shows a bullet entering his shoulder from behind. The county never released the name of Masters's killer; he was identified as Officer David Ziants only when the county attempted to quietly fire him two years later. Squabbles among Masters's family, combined with Virginia's two-year statute of limitations on wrongful death suits, prevented the matter from ever going to court, so the county has never explained Masters' killing.

"I still don't have anything," says Barrie Masters, a retired Defense Department analyst. "They say the law says they don't have to release any information as long as the investigation is going on. They just say the investigation's still going on."

Over time, Fairfax authorities have learned that if they ignore a problem, it'll often go away. Nicholas Beltrante, a former D.C. cop turned police watchdog now living in Fairfax, says area residents are too rich and content to get worked up about the occasional taxpayer-funded slaying. He tried holding a town hall meeting to compel the county to act after the Masters killing. Only six people showed up, as he recalls.

"The citizens of Fairfax County see this happen and they say, 'Oh my god that's terrible!' And the next day they forget about it," says Beltrante. "That's not the case in Ferguson or Staten Island. There, there's an outcry, and they get results."

But the stall tactics that served Fairfax officials so well in the past have backfired horribly in the Geer case—because at the same time Geer's family and friends were getting nowhere with their pleadings for officials to tell them who killed their loved one, the world changed a bit. Ferguson and Staten Island happened. And all of a sudden, police killings of unarmed citizens were the front-page news they should have been all along.

For reasons New York mayor Bill de Blasio is coming to understand, the state, local, and federal politicians who represent Geer's neighborhood have remained content to let the police close ranks, just as they allowed the police to withhold information after Culosi's killing. It took an outside lawmaker to shine a light on Fairfax. No doubt because of the tumult around the country in 2014, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA) is threatening to make a federal case out of Geer's death. In November, Grassley started asking questions of Fairfax County officials. He sent a letter clearly laying out many of the unresolved questions surrounding the case to police chief Edwin C. Roessler, asking him to "please explain why FCPD refuses to disclose even basic information."

And now, there's movement. On Dec. 22, a judge in Fairfax County Circuit Court gave the county government 30 days to release just about everything they and the police know about the Geer case, including the name of the officer who killed Geer and the names of civilian witnesses to the killing. Grassley remains peeved by the failure of the county police department, board of supervisors and county attorney to do anything to resolve the Geer case. "Transparency and accountability are sorely lacking in this case," Grassley says. His staff has been whispering that he might call a hearing on the matter when he takes over as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee this week. Grassley's involvement, plus the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, a long way from Fairfax County, guarantees that Geer's case will get the attention that Culosi's never did.

On Monday, around the time Grassley was haranguing the county once more, Fairfax released the name of Geer's killer: PFC. Adam Torres. In the same statement, police said for the first time that Geer "was displaying a firearm that he threatened to use against the police." Stewart says he never saw any weapon. Video of the standoff doesn't show one, either.

A rally is scheduled for Thursday at the Fairfax Police headquarters. It's being organized by a group called Justice for John Geer, which claims more than 200 people will attend. Beltrante is dubious that many locals will show up. "I hear it's going to be cold," he says.

The police are being represented in the Geer case by Assistant County Attorney Kimberly Baucom. Her husband, David Baucom, was the Fairfax County undercover cop who bet taxpayer money on football with Sal Culosi and called in the SWAT team that killed him.

The shooter, Bullock, is now retired. David Rohrer, the police chief during the Culosi debacle, got moved upstairs: he's now deputy county executive. In 2011, five years after Culosi's killing, Fairfax County paid his family $2 million to settle the lawsuit.

Anita Culosi says she's following the Geer case closely even though it "just opens up old wounds." She likely won't be at the Geer rally, and says she's wary of being tagged as anti-cop. Her brother, also named Sal, was a New York police officer killed in the line of duty in 1961. She named her son after her brother, she says.

Anita visits her son's grave every Tuesday, because he was killed on a Tuesday. She writes to him on the 24th of every month, since he was killed on the 24th of January, and on holidays. Her posts appear on a memorial web site she pays to keep online.

She used her Christmas Day entry to update her dead son about the Geer case. The punctuation is hers.

Dad commented on a newspaper headline...that referenced a judge's ruling...that ordered the FCPD ...to release information...they have been withholding...from another victim family...whose unarmed loved one...was killed by a FC police officer...in Aug. 2013. The family has been waiting...since then...for their questions to be answered...so I don't think...the FCPD has learned anything since 2006...and the shame is on them ...once again.

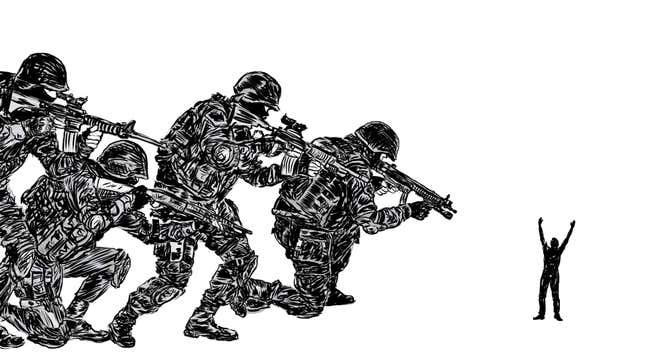

Illustration by Jim Cooke