This week’s must-read on the ongoing daily fantasy sports mess is Jay Caspian Kang’s piece for the New York Times Magazine. It’s sort of a hybrid personal odyssey/news item, beginning with Kang recounting how he gradually slipped into the DFS life by playing against friends, but eventually couldn’t resist entering larger contests, where he found himself consumed by sharks entering dozens of entries to skim their profits from minnows like him.

That’s where the profits are, as we’ve long known: something like 90 percent of the prizes go to just 1.3 percent of users. What Kang’s piece reveals is that DraftKings and FanDuel know its power users are gaming the system through the use of scripts, to enter and adjust hundreds of lineups within minutes. FanDuel claims “anticompetitive” scripts are banned, but admits the company can’t or won’t do anything to detect or discourage them.

Sacco also said that one reason FanDuel allowed some scripting was that the company could not completely stop it. This confirms the suspicions of many in the D.F.S. community who believe that DraftKings and FanDuel do not regulate scripts because they have become so sophisticated that the companies simply don’t know how to detect or disable all of them.

In light of DFS’s rock-fast policy position that it doesn’t need to be regulated, “we can’t stop the cheating” is a pretty big admission.

(Left unsaid: companies that make their money on entry fees have no incentive to stop people from entering as many times as possible.)

These scripts are just another example in the litany of valid gripes with the way DFS is currently run: a select number of users with the time, inclination, and bankroll to gain a competitive advantage over the vast majority of users will take you for all you’re worth. Once again: you will not win money playing daily fantasy.

I did, though.

Kang is still playing, even though he knows the odds are against him. That, I think, underscores a point that a lot of the screaming about daily fantasy from media outlets, including us, fails to acknowledge. For all its shadiness, for all the likelihood you’ll lose money, it’s still an awful lot of fun to play—and money is being paid out. If we’ve accepting gambling as a whole, I don’t know why we can’t accept DFS on the same terms: we know the house is running a con, but because we know it, then the players themselves aren’t necessarily being conned.

I was somewhat late to the DFS party. I had seen and been turned off by the flood of ads this summer, but even after football started, I felt no inclination to play. I had read all the reports, knew about the loopholes that stacked the deck against me, and couldn’t see the appeal. I even wrote about how it was a great idea in theory that was doing nothing but harming this country’s chances at legalizing sports betting.

And then Drew started playing. He did it for “research,” to be able to write intelligently about it. He found what most people do. Intellectually, you know it’s evil, a contraption built to trick you into emptying your wallet. Emotionally, it’s addicting as hell. He kept playing. He kept talking about it in our work chat room. Finally, I got curious enough. I put in a hundred bucks on DraftKings (complete with a “matching” bonus, that at my current rate of play, I won’t be able to fully touch for years), and played against Drew in a head-to-head NFL game for five bucks. He beat me, winning, minus the vig, $9.00. He bragged about it at work the next day. I wanted revenge.

The fun in daily fantasy—at least where I found it—is in everything but the money.

I’m a low-stakes gambler, because I genuinely enjoy the act of gambling. I go to Atlantic City a couple times a year, camp out at the $15 blackjack table, and play until I don’t want to anymore. I’m happy enough going home down a few hundred, because I think that’s a fair price to pay for the entertainment of playing. I know that casino odds are against me, just as DFS’s are, and I’m willing to accept that for the chance to do something fun.

Think about regular, season-long fantasy football. What’s the single most fun part? Drafting your team. Second is watching the games as you follow your team’s stats—your monetary investment, as small as it may be, gives you an emotional investment in sporting events you wouldn’t care about anyway. I love that I can be made to give a shit about some meaningless Bengals-Chargers late game. That’s three hours of my life given meaning.

In third place in the hierarchy of season-long fantasy benefits is actually winning the league, which you probably won’t do, and which will happen just once a year if it does. Daily fantasy’s brilliance is right there in the name. If I’ve got nothing to do tonight, I can throw a few bucks down, have the fun of picking a team and following a slate of games, and maybe—probably not—win something small. The winning barely matters. I get to take part in the most fun parts of fantasy every single day, if I want to.

It’s seductive. While I kept playing Drew and Kyle head-to-head, I started entering the big contests, though always with low entry fees. Five dollars on an NFL pool, say. Then, I expanded to mid-week. Three bucks on a slate of NBA games here, two bucks on hockey there. (I play mostly hockey these days, because I figure my knowledge of the sport is in a higher percentile than it is for any of the others. While I’m confident that’s true, there’s no reason to think the people I’m playing against represent “hockey fans,” which is a very different pool than “people who play hockey DFS” and are going to eat my lunch anyway.)

I would’ve been totally content with that—winning some, losing more, slowly draining my pot until it was gone. Maybe I would have put some more in; maybe I would have decided I’d had my fun and was done. But the daily fantasy operators don’t want to run the risk of you getting bored. They want to keep you coming. So they offer you free shit.

DraftKings ran a Christmas-themed promotion, part of which was free entry into a few low-stakes contests. Why the hell not? I entered, and didn’t win any, but by dint of accepting three of their four offers, I was given a free entry to a Christmas Day NBA pool, with a $1 million top prize.

I don’t know shit about basketball, but this was bigger stakes than anything I’d played before—the entry fee is regularly $20. So I picked my team based on, well, not much. I’ve heard this guy’s name a lot recently, maybe he’s a steal. Oh, he’s playing against a weak defense, maybe he’s undervalued. Hey, it’s Chris Paul, he’s really good. That sort of thing.

And then I mostly forgot about it. I checked in on the Heat/Warriors game for a while, zoning out whenever Andrew Bogut was off the floor. Looking at the day’s scores later, I half-noticed that some of my low-cost draftees, like Enes Kanter and D’Angelo Russell, had had pretty darn good afternoons. One of my expensive players, Kawhi Leonard, had a monster statistical game. In retrospect, it was the ideal DFS lineup—some hidden gems, and projection-beating performances from the known quantities.

By that evening, I was checking the app on my phone pretty regularly, since it updates your potential winnings in real time. (DFS is made for killing time on your phone. I bet 30 percent of lineups are drafted from the shitter.) I was in the money. I think I was sitting at around $80—sometimes slightly up, sometimes slightly down—and I was psyched. I still had Chris Paul to play in the late game, but I didn’t really care enough to stay up for it. After all, me watching wouldn’t influence his performance. So I went to bed.

When I woke up, I showered, made my coffee, and read the news. I had forgotten all about my team. When I turned on the computer, there it was: the morning-after email. Every time you win, DraftKings emails you. (Subject line: “Valued customer, you won!”) I wonder what their return rate would be if they emailed you every time you lose.

I clicked on the email, and I had won $2,000. Chris Paul had had a good game.

I texted just about everyone I know that I thought would care, and even some people I knew wouldn’t. I hopped into the work chat to see who was awake at 9 a.m. the morning after Christmas. No one was. I announced it anyway. I didn’t want Drew to have to wait one extra second to know that I’m good at this thing he’s not good at. (Yesterday, Drew revealed that his DraftKings account is down to 40 cents.)

And that’s about when I panicked, because money in my account and money in my bank are two very separate things when it comes to internet gambling. I had a very brief phase in college when I was playing blackjack and even slots online. Always for low stakes, until one drunken night, a series of events that remains blurry in my memory led to me sitting on $10,000 in profit. At that age—at any age—ten grand would have no-shit changed my life. I tried to take it out, and the site—shady and semi-legal—made that as difficult as possible. I don’t remember all the hoops I’d have to jump through to withdraw that money, but I remember it would have taken weeks to be released. So I decided to keep playing. That same night, my $10,000 profit disappeared completely. My cheeks still get hot with embarrassment and regret when I think about it.

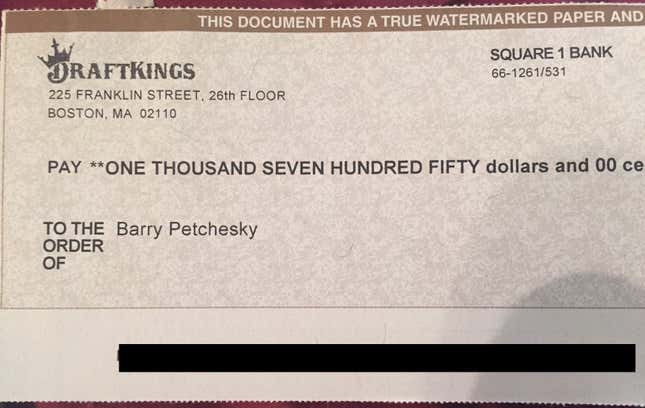

DraftKings made it easy. I filled out a W9, answered a few questions to prove my identity, and the money was mine. They refunded my initial $100 deposit to my credit card, and mailed a check for the rest.

You will notice I left some money in my DraftKings account. Every good gambler knows not to walk away from the table when you’re up.

I’m still playing. Still two- and three-dollar games, though perhaps slightly more often than before. It’s still fun to have that low-level, background-noise sort of awareness that I have stakes in sporting events. But I’ve made my big score, and given my rate of play and various attorneys general’s looming crackdowns, I don’t think DraftKings will exist long enough for me to lose it all back. That’s only because I’m lucky, though. If I had a less healthy relationship with betting, I could easily see upping my antes, using my newfound bankroll to chase higher and higher prizes that I’d almost certainly never win. For every person like me whose number comes up and immediately cashes out, there are others who pump it right back into play. Daily fantasy worked for me, but that doesn’t mean I don’t know how it works. I won big, but the house wins bigger.

Image by Sam Woolley.