If you’ve been on the internet this month, you’ve definitely been exposed to the most successful ad in the history of Twitter. Millions of people and countless media outlets have propagated the heartwarming story of a giant corporation buying a priceless amount of advertising for close to free. If you, like me, are one of the apparently few people who thinks it’s gross to willingly help a multibillion-dollar company expand its brand reach without them even paying you to do it, then I have some good news: You actually don’t have to do that.

On Tuesday, Nevada teen Carter Wilkerson was finally rewarded for his incredibly successful efforts to spread awareness of and goodwill toward multinational fast food chain Wendy’s. Some cheeky Twitter banter between Wilkerson and the brand’s account a month ago led to this tweet in which the then-anonymous Wilkerson sought help from his fellow Twitter users to reach the 18 million retweets Wendy’s had demanded in exchange for a year’s worth of free chicken nuggets. Just over a month later, Wendy’s awarded Wilkerson his year of nuggets right around the time the tweet became the most retweeted tweet in the history of Twitterdom—surpassing Ellen DeGeneres’s three-year record-holding, star-studded Oscars selfie that featured some of the most famous people in the world.

More than three and a half million accounts have retweeted Wilkerson’s message, which put it into exponentially more timelines—including, I bet, yours. News organizations from the New York Times to the Verge covered the story, pushing it out to even more potential consumers. In exchange for an ad with that kind of reach, a year’s worth of chicken nuggets—let’s say Wilkerson actually orders some every day, which he won’t but would still have a value under $1,000—is quite the bargain.

Wilkerson and Wendy’s are not alone. This kind of native viral advertising is all the rage now. Just check out a recent article from Indy100, the Upworthy-esque content farm cousin of respectable British paper the Independent, about a similarly cheeky if lower stakes back-and-forth between one Twitter user and a number of brand accounts. “Social media seems to be the new way to get free things,” the article starts, right away stating the issue in the exactly wrong way. These people #engaging with the #content of a #brand aren’t getting free things; they are being paid (poorly) to advertise those products. And everyone—from the people tweeting the brands, to those liking and sharing those tweets, and the outlets earnestly covering the ads in search of cheap traffic—is complicit.

Let’s look at the ads Indy100 wrote about. (And let’s not mince words: these are ads. What else is a publicly shared message featuring a consumable product positioned in an effort to make that product and, by extension, the brand look good if not an ad?) That story started with this tweet by artist and social media presence Hector Janse van Rensburg, also known as Shitty Watercolour:

This is either a funny tweeter’s sendup of the very phenomenon at hand—that social media is not always what it appears or purports to be, and is overflowing with pseudo-candid pictures and messages that in reality are unlabeled paid advertisements, playing off that strange mix of authenticity and commercialism endemic to this kind of internet microcelebrity—or it is a calculated attempt by a man fluent in paid brand strategizing. It can be both; it doesn’t matter either way. What does matter is that the soap brand reached out to van Rensburg, sent him some “free” products, no doubt out of appreciation for his trenchant satire, which led van Rensburg to do another, even more popular tweet playing off the same gag, this time incorporating an additional brand:

The soap brand engaged with the car brand, and the car brand sent van Rensburg a comedic gift—he asked for a car so they sent him a toy one, ha-ha!—happy to carpool on this viral motorway. All of this cost each company, what, 20 or 30 bucks? To reach millions of potential consumers. No traditional ad has ever had that kind of return.

Man tweets at brand. Brand sends man product. This, you may be saying, is not a story. Or at least not one anyone would want to read. So, in an effort to juice the return on their coverage of this at best mildly entertaining scenario, Indy100 stuck on top of their article an intentionally deceptive headline: “This artist got a free car thanks to Twitter and some shower gel.” I’m sure the writer needed a whole bottle of Hip Brand’s Super Sudsy Shower Gel to wash away the shame—a bottle which Hip Brand would be all too willing to provide for free, naturally.

This whole nasty business is a perfect reflection of the online sharing economy that is fucked up and stacked against you. It’s wild how readily real live human beings—often smart ones, too, who would generally express skepticism for this exact kind of corporate intrusion—will accept the presence of and even participate with brands on social media. The only requirement is that the brand be savvy enough to mask the corporate interests driving them with effective internet-speak. It was fun to laugh at at and shame inept brands tweeting about how their pancakes are “on fleek,” or Wendy’s itself tweeting Pepe memes, back before brands learned how to effectively engage with regular Twitter users. The “How do you do, fellow kids?” nature of it all provided an easy target for ridicule. But only the bad guys seemed to have learned any kind of a lesson from all of this.

A subtle, with-it meme reference here, a jokey reply to a customer there, and a few random freebies sent every once in awhile to incentivize user engagement with the added bonus that the story might blow up into the next #NuggsForCarter viral hit, and you’ve got yourself an effective, nationwide advertising strategy for just the cost of a couple cheap social media managers. Once scorned for their tone-deaf social media presences, the brands have adapted and are swim undisturbed alongside the real people online.

People on the internet, meanwhile, haven’t learned a thing. Though these sorts of engaged social media users skew young and nominally leftward, they don’t actually distrust corporations, or understand that those corporations’ interests are not their own. What the average person is most put off by isn’t naked revenue maximization, but instead by failed imaging. Most people using and writing about the internet desire nothing more than to be successfully marketed to. This is not a worldview that believes Brands Are Bad. Instead, it’s one where there are Good Brands and Bad Brands, and when a Good Brand that you root for does something cute and shareable it’s perfectly fine to join in on the fun, but when a Bad Brand does something similar, only then is it time to be critical and assail the brand for the same shameless self-interest that the Good Brand gets away with thanks to its prettier packaging.

Case in point: Aston Martin is seen as smart and cool for piggybacking off Radox’s ad with van Rensburg; United Airlines is immediately called out for being dumb and bad for doing the exact same thing with the Wendy’s campaign. “How do you do, fellow kids?” is funny not only because it’s a cop trying to infiltrate a high school—a horrific thought on its own—but because he’s incompetent at it. There is the objectionable act itself and the presentation of the act. The internet welcomes the invasion of cops into their inner circles, just so long as the cops give them a knowing wink.

So who benefits from this? The brands, obviously; they get free exposure and permission to lower their ad spends. Wilkerson won, too, in his smaller way; he gets his nuggets and a cool story. But that’s it. Consumers should remember well that when they’re not paying for a service—reading blogs or using social media—they are the product.

Ultimately, it’s the media’s role in this process that’s the most disturbing and self-defeating. Journalism as an industry depends on two factors in order to survive: advertising and public interest. A Wendy’s or Radox ad showing up in a paper or on a blog in itself isn’t notable. But in the modern economy, where traditional advertising efforts have proved of questionable efficacy and newspaper and magazine circulations are forever down, outlets find themselves directly chasing readers and counting on those numbers to be monetized eventually.

The problem comes when journalistic outlets publicize Wilkerson’s tweet or van Rensburg’s tweet or a sweetened water company’s Derek Jeter ad or Tom Brady’s Stretchy Workout Stuff—in other words, run advertisements—outside the traditional advertising process. Wendy’s didn’t pay the Verge for the publicity their credulous article gave the company, just as Tom Brady didn’t cut SI.com a check to shill his pseudoscientific workout gear. Yet publicize these ads they did, not for the direct payment they would’ve received had Wendy’s bought a banner ad, but for the easy traffic promised by glibly positive, shareable stories. And like Wilkerson’s payout of a year’s worth of nuggets for all he’s done for Wendy’s, the media is cutting itself a raw deal.

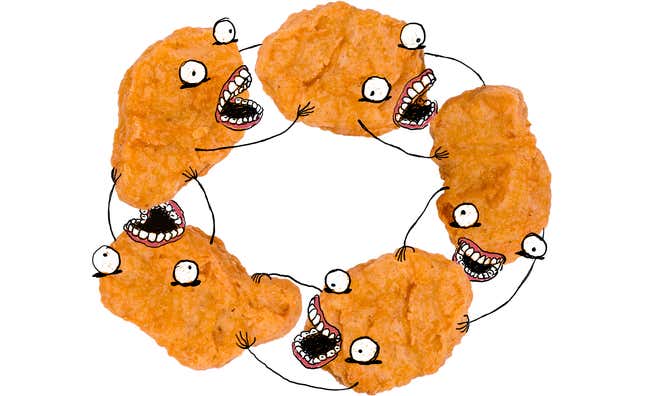

The fact is, new media hasn’t yet figured how to effectively monetize traffic, at least not as efficiently as the old system worked. It’s why Twitter hemorrhages money; it’s why independent news sites of any scale quickly glom on to VC money or fold. (N.b. this site’s original parent company, which declared bankruptcy because it couldn’t afford the process of appealing a judgment against it.) Web traffic is nice but it isn’t sustainable, and without the dependable, significant revenues previously offered by traditional print advertising, a lot of media outlets simply can’t afford to spend their limited money on doing compelling, original, or investigative work, the sort that would make them appealing to advertisers. Instead those outlets chase the cheap traffic, and nothing is cheaper or more guaranteed traffic than sharing life-affirming stories of Good Brands doing Good Things. These stories undercut traditional advertising even more—why should Wendy’s hire an agency or do banner ads when one smart young social media manager can do so much more?—which then even further limits options for the media outlets. The snake is not just eating its tail; it’s shitting chicken nuggets into its own mouth.