Warmed up and stripped down, 15 blade-thin runners milled on the track, game-faced, gathering themselves. A few words between them, Swahili and English—“20 seconds ... 10 …”—and the amorphous group coalesced into a single-file line, shuffling. Scott Simmons had not finished saying, “Go!” when the first in line clicked his watch, ducked his head, and sprang forward, the same sudden animation rippling down the line.

A lap every two minutes, 25 times, all between 61 and 64 seconds. “Let’s go guys … 58, 59 …” and the train left the station again. After the sixth 400, there was no talking between laps. Breathing. Feet tapped the red track. “58, 59 ...” Laps 19 and 24 were hammer sessions—all out, 51 to 54 seconds per, same rest. A phantom bond between them—keep up, one more. A steeplechaser ran out in lane two, covering hurdles while maintaining pace. All this, in the thin blue air of Colorado Springs.

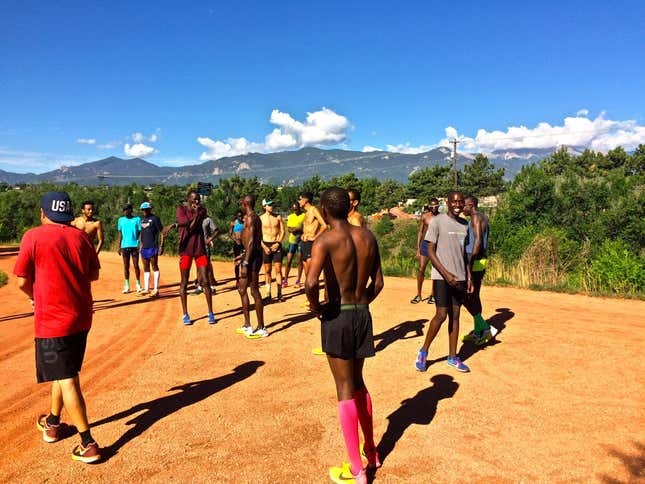

Some of the bodies strewn around the infield after the workout were members of the American Distance Project (ADP), and some were from the Army’s World Class Athlete Program (WCAP). When Scott Simmons established ADP six years ago, the training group was mostly made up of Colorado Springs locals, individual runners looking for training partners and a coach. WCAP, an Army recruiting perk and public relations strategy, had produced only one world class runner since its start in 1997. Neither group had any runners on the 2012 Olympic team.

Over the next four years, ADP and WCAP joined forces and grew, in number and pedigree, and transformed from U.S.-born locals to predominantly Kenyan-American men, runners who’d originally come to the U.S. on track and cross country scholarships. Suddenly, the combined group was a powerhouse in the distances.

In 2016, four WCAP runners made the Olympic team, including Paul Chelimo, who earned a silver medal at 5,000 meters. The last time an American man medaled at 5,000 meters was in 1964. One year later, seven runners from ADP/WCAP earned a spot on Team USA for the Track and Field World Championships in London, more than from Nike Oregon Project, more than from any other training group aside from Bowerman Track Club.

“Now the U.S. won’t be embarrassed, we won’t be lapped anymore,” Chelimo told me. “We don’t need people who quit when it gets hard.”

5-feet-11, 126 pounds of intensity, Chelimo’s earned the right to talk smack. ADP/WCAP has raised the level of competition, and they’ve done so without a war chest of shoe company dollars. U.S. distance running has been dominated by corporate-sponsored groups—Nike Oregon Project, Bowerman Track Club, Oregon Track Club, NAZ Elite, Hoka NJ-NY Track Club, Brooks Beasts, and the like—since the early 2000s. ADP/WCAP’s success comes despite offering little in terms of athlete support—no group-wide sponsorship, no stipends (WCAP members get regular Army pay along with regular Army responsibilities), no housing, no state-of-the-art gym facilities or dedicated medical teams.

So how did it become a powerhouse? I went to Colorado Springs to find out.

Other than Dan Browne in 2004, WCAP has had few distance runners, and those few didn’t make much of a ripple at the national, much less international, level. That’s probably because joining the Army—a decision that brings with it a 40 hour-a-week job, infamous bureaucracy, and the very real possibility of front-line action—has never been an attractive option for a U.S. citizen who’s capable of, say, a 3:39 1,500. (That’s the WCAP qualifying standard for 1,500 meters)

That changed in 2009. Joining the Army has always been a path to U.S. citizenship, but that year the Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI) program made it possible for non-citizens with certain skills or language ability to dispense with getting a green card before applying for citizenship, shortening the process to about six months. Due to Army missions in Africa, MAVNI focused on enlistees who could speak English and Swahili, which is to say, Kenyans. Starting with 1,500 spots per year for non-citizens, MAVNI expanded to 3,000 spots in 2015, and again to 5,000 in 2016, then was abruptly suspended in 2017, a victim of the Trump administration’s immigration policies. So starting in 2009, the Army had quite a few soldiers, mostly Kenyans, who could and did hit WCAP’s qualifying standards. All of the distance runners now in WCAP joined the Army through the MAVNI program between 2010 and early 2017.

To be clear, MAVNI enlistees are not “given” citizenship; each soldier is responsible for submitting all of the required paperwork after attending basic training. Once in the Army, acceptance to the WCAP program is neither guaranteed nor permanent, even if the candidate has posted the stiff qualifying standards. And WCAP athletes are not paid to run for the Army in the same way that Galen Rupp is paid to run for Nike. They get more time to train than regular soldiers, but not all day, every day. They’re paid according to their rank, and get time off to train and compete, but are still expected to perform their Army job part-time (Hillary Bor went from the track workout I watched to his job in accounting), attend ongoing military school, and deploy with their unit if necessary. WCAP does confer some immunity to deployment, but it’s not a guarantee. Elkanah Kibet, for example, has served in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and Julius Bor, a sub-four-minute miler, recently returned from a year in Afghanistan. He was training in the base exercise yard when a suicide bomber attacked, killing three of the other soldiers in the yard at the time.

WCAP coaching had been a bit patchwork prior to 2012—on a year-to-year basis they contracted Scott Simmons in 2013 and 2014, but Dan Browne took the reins in the lead-up to the 2016 Olympics. Browne brought Leonard Korir, Paul Chelimo, Shadrack Kipchirchir, and one other WCAP runner to Portland, Oregon, while the rest were working out with Simmons in Colorado Springs. It was confusing.

“The former secretary of the Army went to Rio and was amazed how few people knew we had four Olympians,” said WCAP co-coach Sean Ryan. As a result, changes were instituted: All WCAP runners were brought to Colorado Springs, with Ryan and Simmons collaborating on coaching, and Ryan handling budget, paperwork and PR. He’s a natural for the job. A career Army guy without the drill sergeant demeanor, Ryan grew up in Colorado Springs, ran in high school (the same one that Adam Goucher attended) and college, and eventually posted back in the Springs with Special Forces. Having a dedicated, high-ranking officer who knows something about distance running and can advocate for the athletes, Simmons said, has been vital to WCAP’s expansion and success.

“If Biya [Simbassa] wants to run in Monaco, Scott can call the race director the week before and arrange it,” Ryan said. “That’s not the case with WCAP.” To release the WCAP soldiers from duty, he has to get legal paperwork from the race director saying exactly what they will pay for and what WCAP will pay for, and get that approved on all levels of command. That requires he submit paperwork about a month in advance. “World Cross Country was held in Uganda this year, where Boko Haram is active. You can imagine trying to get security clearance for five U.S. soldiers to travel to Uganda.”

The expansion of WCAP in the last eight months was a concerted effort to build a “powerhouse” team. “I sat down with Scott and said, ‘Where’s our bench?’” Ryan said. In addition to injuries that other groups have to deal with, WCAP soldiers may be taken off the active roster for extended periods for ongoing military training or deployment. Ryan and Simmons’s plan is to build up the team, ideally to three athletes at every distance, so they can cover absences that occur. They’re looking for these other WCAP members amongst the regular Army by publicizing the distance running team, searching their own ranks more aggressively, and promoting from within. “Maybe they missed the [WCAP] qualifying time by a few seconds, then they were deployed or got married, and life got in the way,” Ryan said. “We want to bring those people to WCAP, let them train with the team for 18 months and see what they can do.”

Simmons writes workouts for the whole group. His training philosophy is pretty basic—two main workouts and a long run per week; the hard stuff hard and the recovery very easy. Simmons talked about the organization of the workouts, the specificity, the volume and intensity, and the distance of the long run as being what made this training program so effective. But all elite runners train hard and take easy days. They’ve all got a killer workout like 25 x 400, so when members of ADP/WCAP uniformly credited hard work and dedication with their success, I wondered what was different about their hard work and dedication. Isn’t it that the athletes are better, more able to accomplish faster workouts and greater volume, rather than the training program being better?

They all said they’re running more volume, and faster, with less rest between intervals than in their previous programs—whether college or a previous professional group—and that the level of training has further increased in their time with ADP/WCAP.

For example, they hit the 400 workout every month or five weeks, but even earlier this year, the laps were slower, and fewer runners were able to complete all 25. Simmons said earlier in 2017, this same group could not do the workout I witnessed.

“I’ve never seen a workout like that 25 x 400, not at that level,” Simmons said. “But it’s been a progression—as they get better, they train better. I don’t believe these guys are especially talented—they’ve avoided injury and have progressed to that point.”

So there’s a feedback loop—as they get better, they train better. Simmons’s workouts are tailored to continue to challenge the athletes in the group. As their fitness improves, his workouts have become longer, faster, with less rest. And those workouts, in turn, have helped them win races and raise the group’s profile, which has attracted higher-caliber athletes.

Sam Chelanga, an NCAA champion, and Stanley Kebenei, who signed with Nike right out of University of Arkansas, had been training in Tucson with coach James Li. They visited ADP after both failed to make the 2016 Olympic team. Simmons said, after participating in some workouts, they realized the hard workouts they had been doing were not the right kind of hard. To be fair, though, Kebenei said he’d been unable to give Li’s program a chance because it was simply too hot in Tucson.

Haron Lagat, a WCAP steeplechaser, joined the group this past April after training alone for nine years. Though he was a professional runner during that time and no doubt training with intensity, he struggled to stay with the others for weeks after he joined the group, such was the jump in level of training.

Hillary Bor was unequivocal about crediting Simmons’s support and the training program with his Olympic berth. “The key is in trusting the coach and the training process,” Bor said. “The reason I made the [2016 Olympic] team is because of Scott Simmons. He kept telling me I had the ability, even though I’d never run under 8:32.”

Though he was a standout at UNC-Greensboro, Paul Chelimo’s training was interrupted by injuries. He went from good college runner to Olympic silver medalist, Simmons said, because he’s been injury-free for two years. That points to smart training.

Michael Jordan—“Same name, different game”—was a little more specific about what made Simmons’s version of “hard” different from what he experienced at his previous home with the NJ-NY Track Club. “We did 1,000s but with like eight minutes rest in between. I got faster, but then when I got in a race, I was looking for that big rest. Here, I’m running faster with less rest. [This program] makes you grittier, and that’s what it takes to race well.”

Jordan is a testament to the effectiveness of Simmons’s program. He did not grow up in Kenya; he grew up in Gary, Indiana. Shortly after joining ADP, he discovered he’d be training with several Olympians and some NCAA champions. And he’d never been at altitude before.

“I was a D-II guy to begin with, and out of shape on top of it,” Jordan said. “I was like, Are you serious? I can’t train with those guys! But Simmons told me, ‘Do as much as you can. As long as you progress, that’s all that matters.’”

He ran for the first two months with ADP member Elvin Kibet, who is married to WCAPer Shadrack Kipchirchir, then joined the lads, hanging on a little longer before being dropped every week. It took him a while to realize he’d get faster by running super slow on easy days, “like 8:50 for the first mile and 7:50 by the end.”

Nine months ago, Jordan said, he couldn’t have dreamed of doing the 25 x 400 workout. Every workout he’s done this summer has been a personal best, and his steeple time has dropped by five seconds since he joined ADP.

In fact, Simmons said, every member of WCAP/ADP has improved since joining the group, through a combination of better and more consistent training, which is to say, avoiding injury. Improvement, by every athlete, every season, is how he measures the effectiveness of the training. Improvement by NCAA champions and pretty good D-II runners points to a better training program rather than more talented athletes.

Biya Simbassa graduated from the University of Oklahoma before he’d come close to his potential at 10,000 meters. His modest best of 28:42 limited his post-collegiate choices, and the quality of races he could gain entry to. Simbassa joined Team USA Minnesota where he started building his mileage and fitness. Seeking altitude and more training partners, he joined ADP in November 2016. Within seven months, he’d improved by over a minute to 27:45.

Simbassa’s experience highlights a key ingredient in ADP/WCAP’s training success: critical mass. One of the hallmarks of Kenya’s running culture, and a factor in its success, is the sheer number of hopefuls taking part in the Thursday tempo run or Tuesday track session. On any given day on the dirt roads of Kenya, 40, 50, 60 runners show up for workouts. Big names and no names—there’s always someone who will push the pace, always someone faster to chase. There’s motivation to show up and keep up, lots of brethren to share the pain and the victories. At any given time, some will be injured or traveling or taking a break, but there are plenty to take their place.

In the U.S., the few pro runners—and this term is used loosely by some who are only getting $5,000 worth of clothing and shoes in a year—try to separate themselves from amateurs. Individuals and groups, many with less than 10 members, are spread around the country. Corporate-sponsored groups are not generally open to local folks, those who aren’t official members, joining the workouts. With widely scattered, exclusive groups, it’s rare to have six or seven athletes doing the same workout. Then, if some of that number are injured or traveling or on a different schedule, runners end up working out alone. Motivation is tough, and improvement tougher. The proven power of the group is lost.

With 26 core members bolstered by friends, relatives, or Army regulars trying to make the WCAP standards, ADP/WCAP has hit critical mass. There were four marathoners doing a marathon-specific tempo workout when I was there. The seven going to the World Championships pulled each other along, and those doing a shorter workout stayed and cheered on the ones grinding out six or seven miles. Even Joe Gray, the only mountain runner of the group and self-described lone wolf, said he has benefited from having plenty of people to push him in workouts, and “learning not to train when I’m tired.”

Augustus Maiyo, a WCAP marathoner, said this training style is familiar to most Kenyans. “It’s hard, but this program suits most Kenyans because this is what they do in Kenya,” he told me as we talked in his backyard. “Local guys, most of them will get injured because they haven’t done it before. This program isn’t for everyone.”

Simmons chose Colorado Springs as strategically as he plans the workouts: It’s at altitude (no need for altitude tents or expensive travel), there are a plethora of soft trails (easy on the mind and the body), and the temperate weather allows outdoor training year-round (no treadmills or indoor facilities). They do drive the 20 miles up to Woodland for super-altitude training—9,000 to 9,500 feet. Simmons doesn’t advocate much strength work or cross training; he’s not big on gadgets or supplements. None of the group has been found to have asthma or thyroid problems, nor have they filed for any Therapeutic Use Exemptions (a waiver that allows an athlete to use a banned substance if medically necessary).

“They’re successful because they’re American,” Simmons said, not just to be contrarian. “When I was in Kenya, I saw how starkly different naturalized Americans were from Kenyans living in Kenya.” Kenyans living in Kenya, he said, lacked the national infrastructure and discipline to be successful in Kenya. A lot can go wrong in Kenya, and a lot does go wrong—roads become impassable, electricity is not a given, officials take bribes and pocket athletes’ funds. As Americans, members of the ADP/WCAP group all have undergraduate degrees, many have Master’s degrees. They’re making salaries (WCAP) and enjoying a standard of living that, though modest by U.S. standards, is almost unimaginable in Kenya. The discipline and commitment they’ve learned in American universities and in the Army has made them better athletes, Simmons believes. “I don’t mean to sound exceptionalist, but we’re very lucky as Americans to have reliable electricity, clean water, transportation, a high-quality education,” he said.

“We all came for a better life. It’s the land of freedom, of free speech—everybody wants to come here,” said Biya Simbassa, who came to the U.S. at age 14 with his entire family, refugees from the violence and oppression of Oromos in Ethiopia.

The success of the group and the realization of his American dream are closely intertwined for Stanley Kebenei. One of nine children, Kebenei cleaned carpets and bathrooms while going to college and running at his first stop in the U.S.—Iowa Central Community College.

“Now I’m living the dream,” he said. “Despite challenges, I could come here and train and work tirelessly with this group, and win medals for the U.S. That’s been my focus since I was a child.”

Chelimo said he loved the U.S., loved the lifestyle and the support he’d gotten in college. His brief experience running for Kenya prior to becoming a U.S. citizen made him appreciate the U.S. even more: He ran in the University Games for Kenya and had to share a singlet with his brother. The best way to repay that debt he thought was to join the Army. He bristled at the suggestion he was not fully American: “I could have gone to any other country and been rich, but I love America. When I put on that [Army] uniform, I’m ready to die for this country. Many people here are not ready to do that.” He said winning medals for the U.S. motivated his 110-percent effort.

Leaving family and moving to another country is by any measure a traumatic experience. Everything is different—the language, the culture, the food, the social structure—and that’s hard. Being around people who share your culture and language, who’ve also experienced the struggles of immigration, is easier. It’s more comfortable.

Though they regularly communicate with each other in Swahili, Simmons downplayed the group’s shared experiences and cultural similarities: “I don’t think familiarity or shared immigrant experience is the draw. It’s helped their transition from a social standpoint. They’ve facilitated their own Americanization, but that’s not what drew them to this group.”

The athletes though, credited their common experiences with a sense of belonging, and a level of comfort that influenced their decision to join and stay with ADP/WCAP.

“There are some things about your culture I don’t understand. Sometimes I’m afraid of saying something wrong, so I keep it to myself,” Augustus Maiyo told me. “With others, we’re careful about what we say because we don’t know the boundaries. With the guys, we can say anything. We can talk freely.”

Biya Simbassa said of his visit with ADP/WCAP before joining: “They’re great runners but humble guys. We all came from the same area; we all went through the same struggle. They know all about brotherhood. We just clicked.”

Haron Lagat said, “My agent encouraged me to go to NOP but they only wanted me as a pacer, so I didn’t want to go there. I knew these guys—joining this group was like coming home. I feel comfortable here.”

“We’re not only friends, we’re like family,” Stanley Kebenei said. We visit each other when we’re back home in Kenya.”

“Racism is part of what we have to deal with. It’s usually anonymous, but it’s there,” Simmons said.

For example, Simmons pointed out, white South African runners Mark Plaatjes and Colleen De Reuck, who became U.S. citizens, weren’t subjected to the African-born prefix, nor was Alberto Salazar referred to as Cuban-born during his competitive days. But ADP/WCAPers are often qualified in the media as Kenyan-born or African-born.

“I have friends who call it the African Distance Project,” Michael Jordan said. “No one calls Kyle Merber Irish-American but they call me African-American, and my teammates Kenyan-American. You’re in this weird place with this label in front of American, like a subcategory of American. Not fully American.” Jordan said the naturalized Americans in the group feel some pressure to prove their American-ness, and have been criticized, usually anonymously, for speaking Swahili.

It’s hard to imagine anyone would care too much about so many Kenyan-born runners finding a place with ADP/WCAP if the group wasn’t having so much success. And success, in such short order, ruffles feathers, as three-time U.S. cross country champion Chris Derrick pointed out: “When things change quickly, there’s always some confusion, borderline resentment. People talk about genetic advantage or that it’s somehow unfair that these guys can run for the U.S.”

Eighteen of the total 26 ADP/WCAP athletes are naturalized Americans, born in Kenya. A quick look at the IAAF world records and world bests year to year for distances 1,500 meters to the marathon will show a preponderance of Kenyan athletes. Although circumstantial evidence for some kind of Kenyan superiority in distance running is strong, trying to scientifically tease out genetic advantage from the many other factors that influence distance running success is a fraught business, for which I turn to South African sport scientist Ross Tucker. He’s written extensively on the subject. Here’s an excerpt:

Within the Kenyan population, and specifically, the Nandi sub-tribe of the Kalenjin tribe (this group, incidentally, makes up 3% of the Kenyan population, but almost half of their great international runners), there will be a higher prevalence of favorable gene variants or genotypes than in a population from another country.

The result is that the application of the same training stimuli, plus the environmental factors and culture, will result in a greater emergence of international caliber runners from this population. For every 100 people, there exists a greater probability that an elite athlete will emerge from the Kenyan population than a similarly aged population in say, Australia or America.

On top of this, add the fact that the environment in Kenya (and East Africa) is uniquely suited to distance running. The people, the culture of running, the history of success, the altitude, diet, economic factors and ‘system’ ensure that in Kenya, the training environment is unlike any other in the world.

Kenyan dominance...is the result of BOTH genetic and training related factors, but it is unlikely to be a unique gene that is found only in Kenya. The rest of the world therefore is not destined to be beaten (as Galen Rupp and a number of Americans have shown), but they have to work a lot harder on a system-wide level to identify those athletes with the potential to be competitive, and to expose them to the right environment (without a host of other distractions, which arguably compromise the success of runners).

[...]

There is evidence for early life factors [in Kenyan running success], and one of them is multi-generational ancestry at altitude. It’s not enough to just be born at altitude yourself. There’s some advantage, it seems, from having parents whose parents whose parents were born and raised at altitude too. So even sending a batch of US kids to live at altitude for fifteen years may not bridge the gap to Kenyans.

Not all Kenyans are talented runners, but the Kenyans that American sports fans see—in the NCAA, in road races, and the Olympics—are. Those who earned a scholarship to a U.S. university demonstrated significant talent for running, but the high-profile successes of a few have imbued all Kenyan athletes with an aura of invincibility. Stanley Kebenei talked about the Kenyan reputation: “Other athletes haven’t actually said, You’re just good because you’re Kenyan, but I think some feel that way. You know what? That person has lost to me by thinking that—he’s weak mentally.” Kenyans, he said, can be challenged, but competitors have to think they can do it.

Chris Derrick has been racing the ADP/WCAP runners since his days at Stanford. “This question lingers over running specifically—are Kenyans so genetically superior that no one can compete with them?” he asked. Though he’s aware of the circumstantial evidence that keeps the idea of genetic advantage alive, Derrick’s own experience doesn’t support it. He feels his record against the ADP/WCAP runners has been good, and that he has lost to them more in the last two years because he struggled with injuries during that time while they were healthy and training consistently. “I don’t plan on retiring because these guys are running well,” he said.

Derrick also doesn’t buy into the idea that athletes switching national allegiance is unfair. “When you drill down, the whole structure of the sport is unfair,” he said. In 2012, he ran 27:31 for 10,000 meters and 13:19 at 5,000, had the Olympic A standards, and still didn’t make the Olympic team. He was fourth. There are only five or six countries in the world, he said, that would have that kind of depth at the distances, and the U.S. is one of them. “If I’d been born in almost any other country, I’d have made the Olympic team with those times. It’s not fair but that’s the way it is.”

He does think athletes switching allegiances is an image problem for a sport that gets most attention at Olympic or World Championship events, competitions based on nationality. “If it becomes too common to switch countries, just because it’s easier to make an Olympic team, fans become cynical. It might harm the sport as whole. You’ve got Bahrain and Qatar explicitly buying athletes who never set foot in the country. To the casual observer who doesn’t know the specifics, WCAP may look the same,” he said. (IAAF announced a ban on changes of allegiance in February of this year while they review their policies).

Kebenei saw the infusion of Kenyan athletes as an integral and healthy part of the American melting pot. “I think we’re doing something positive in this country; ADP/WCAP has lifted all of American running,” Kebenei said. “Now everyone is working hard.”

Simmons coached college level track and cross country for 21 years before establishing ADP, and built a reputation for shaping non-existent programs into national title winners, average runners into champions. Because of this history, or in spite of it, he’s inordinately optimistic—he responded to my sarcastic description of his post in Minot, North Dakota as a vacation destination with startling sincerity: “Yeah, it was great!”

Simmons is a purist. He looks for people who want to run for the love of running, just as he wants to coach for the love of seeing people improve. He said he’s never recruited in his entire career. “If you do a good job, athletes will want to be part of the program. With this group, the opportunity to train with the best is motivation; there’s no need to recruit.”

Not recruiting is fine; NOP and Bowerman TC don’t recruit either. But unlike most elite training groups, ADP offers little aside from coaching, training partners, and an ideal location. Again, Simmons has purist ideals. “Too much in our sport is about getting compensated for what you’ve done in the past,” he said. “A lot of people who ran well in college come to training groups asking for shoes or a contract. ‘Can you give me housing or travel?’ They’re asking for things in advance, and then are not motivated once they get there.”

Simmons’s philosophy of neither recruiting nor offering many perks attracted runners from two ends of the post-collegiate spectrum: Those who had, for whatever reason, under-performed in college and couldn’t get sponsorship or support from a sponsored group; and those with a college or post-collegiate record impressive enough to score a shoe company contract such that they were self-sufficient.

Mattie Suver, Michael Jordan, and Biya Simbassa fell into the first category. They’ve cobbled together part-time jobs and prize money to pay the bills while they work to get to the level at which they can score a professional contract.

Suver, a charter member of ADP, said, “The big draw for me was the passion Scott had, and the other athletes had, for running. Everyone was there because they wanted to be there, not because they were getting paid.” She’s still sold on Simmons’s coaching and his idealism: She improved dramatically, and within three years, she and her husband were able to buy a house in Colorado Springs.

Those in the group who have more to share, do so—a rent-free place to stay, shoes, clothing. Simmons doesn’t ask those who are less financially secure to pay him for coaching.

Sam Chelanga, Stanley Kebenei, and Joe Gray all arrived at ADP with professional contracts—coaching, a favorable location, and top-notch training partners were all they required.

Simmons’s philosophy means that he too doesn’t expect to be compensated for past achievements. He makes a modest living from various sources—the Army contract, books, DVDs, coaching clinics, occasional grants, and at one point, a craft beer taproom. He paid his own way to the U.S. Olympic Trials and to the Rio Olympics, and was only allowed a coaching credential to get into the Olympic stadium when Chelimo and Bor made the finals of their respective events.

WCAP runners, with their Army paycheck and health insurance, gear from Nike (until a recently signed contract, the Army purchased Nike singlets and applied the Army logo after market) and some travel expenses, are a self-sufficient bunch. All they needed was coaching and an Army fixer to manage travel.

On paper, ADP/WCAP’s selling points look slim compared to state-of-the-art fitness facilities, first-class accommodations in Park City and St. Moritz, salaries, housing, contracts, dedicated physio and medical teams that other training groups offer, and yet, the group has managed to attract two NCAA champions—Chelanga and Korir—three college standouts—Chelimo, Kipchirchir, and Lawi Lalang—the 2016 World Mountain Running champion—Joe Gray—and two up-and-comers—Stanley Kebenei and Biya Simbassa.

To Biya Simbassa, a shoe contract, stipend, housing—none of those were factors in his decision. “When you can train at altitude, be outside all year, and have good teammates, someone to push you every day—what more can you ask for?”

“When I graduated, ADP/WCAP had very few athletes and almost no profile,” said Chris Derrick, who joined Nike Oregon Track Club right out of college, and now runs with Bowerman TC. “It’s only in the past 18 months, with the WCAP athletes, that it has produced athletes competing at a high level on the track. This is really the first college class that has graduated with ADP being a big name, and getting proven results.”

When WCAPer Shadrack Kipchirchir made the World Championship team in 2015, ears perked up, mostly non-U.S. citizen ears. Then Bor, Kipchirchir, Korir, and Chelimo made the 2016 Olympic team, and magnetically, the group attracted Haron Lagat, Susan Tanui, and Lawi Lalang to WCAP, but also non-Army arrivals Simbassa, Chelanga, Jordan, and Kebenei.

“I didn’t think about joining another group because this is the best,” Kebenei said. “If you want to get better, you go with the best. I wanted to be part of that—that’s why I came here.”

As the 2017 crop of collegiate runners became post-collegiate hopefuls looking for a winning team to join, ADP/WCAP showed up at the U.S. National Championship and filled seven spots for the World Championships. They looked like winners. Top NCAA graduates who used to look to the Portland area—NOP, Bowerman, Oregon TC—suddenly have another viable option.

Kipchirchir recently posted a personal best 27:07.55 at 10,000 meters. That makes him the third fastest U.S. 10,000 meter runner of all time. In the same race, Lenny Korir ran a personal best 27:20.18, making him the fifth-fastest U.S. 10,000 meter runner of all time. Chelimo won a bronze medal at the 2017 World Championships. Nine of the top 10 U.S. steeplechase times have been run by Evan Jager, with Bowerman Track Club. The lone interloper in the top 10 performances is Stanley Kebenei, with ADP. The top three places at Peachtree 10K U.S. Championship were taken by WCAP/ADP runners. Joe Gray placed fourth at the World Mountain Championships in July. That drumbeat of success does not go unnoticed.

Army programs, Scott Simmons’ idealism, 26 athletes, and the American dream came together to create a different model for a training group. As a result, distance running in this country looks different. It looks more competitive.