In a lot of ways, getting old is fine. Your body starts doing a bunch of crazy new gross things, first little by little and then all at once, which is especially fun if you’re a fan of Franz Kafka or David Cronenberg. Old habits downshift into dorkier but less damaging obsessions, and you discover that where you were once drunk as a lord on mass transit at 1:25 a.m. on a Wednesday night, you are now really into like making different types of stews and braises. None of this is exactly cool or even especially enjoyable, but also all of it is better than the alternative. If you want to do something wild or dumb or improvident, you can mostly still do it, although you’ll be sore and regretful for seriously days afterwards. But also you can just remember when you used to do things like that, before, when you were younger.

Or, if you’re Al Pacino, you can literally watch yourself doing those things. (This is also true if you’re someone who makes YouTube videos of yourself sitting in your car delivering monologues about national politics or the New York Islanders or Disneyland vacation hacks, but you shouldn’t do that.) For artists, aging doesn’t just mean bearing the indignities of getting older—weirdly hairy earlobes or brain-splitting hangovers or having a lot of photos of stews/braises on your phone. It’s all of that plus knowing that the collected works of your life, even if they are as brilliant as Al Pacino’s, function as a sort of parallel narrative of you getting old.

To look back at Pacino’s filmography is to watch a masterful performer finding and honing and then changing and intermittently almost losing his voice, oftentimes by literally turning up the volume of his voice. The process is not necessarily linear and not really a narrative—no life story is, except in the sense of days following each other in the same direction—but over the course of decades, character by character and performance by performance, it is possible to read Pacino’s back catalog as a story that exists somewhere between biography and autobiography. What I propose, here, is that we not do that, and instead do something far dumber.

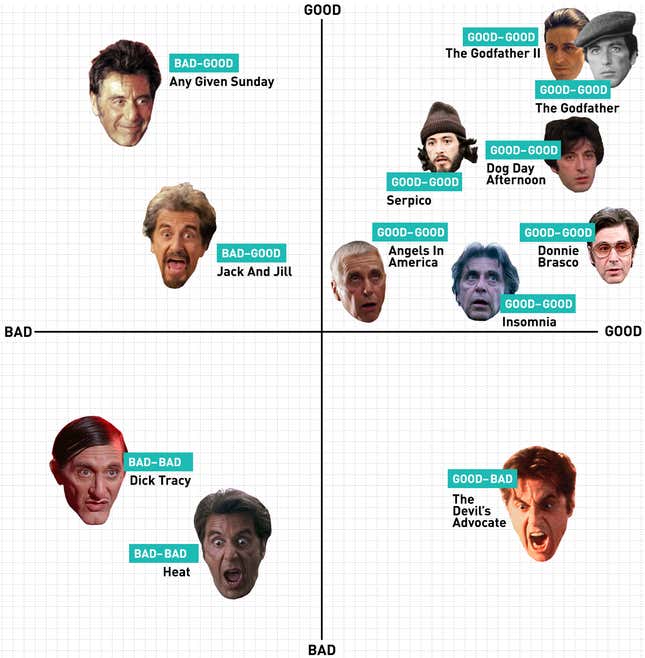

Here is what I propose: over the fullness of his career, which now spans nearly 50 years, it is possible to categorize Al Pacino’s performances in one of four ways. There is Good Pacino and Bad Pacino, yes, but there are gradations within those. There is Good Good Pacino and Bad Good Pacino; there is Bad Bad Pacino, and there is Good Bad Pacino. I have thought about this a decent amount, because as mentioned earlier I am now in the Stews And Braises portion of my dotage and absolutely have the time to do so. Let’s begin.

Good Good Pacino

The most capacious and honestly probably the least interesting category, Good Good Pacino, is also the least surprising. You know most of these performances, because they are the ones that built Pacino’s career and because he gave them in some of the best movies of their time. These performances are heavily concentrated in the 1970's—between 1972 and 1975, Pacino was in The Godfather, Serpico, The Godfather II, and Dog Day Afternoon—and have become progressively scarce since, but they still exist. The more contemporary Good Good Pacino performances are not quite like this, but also and more to the point, there aren’t any other performances like this:

No one can vibrate at quite that high a frequency over the course of several decades—the stews/braises come for us all—but you can find lower-key versions of what’s so galvanic and startling in that Dog Day Afternoon performance, and some of the same strange moments of invention and surprise, in later Pacino roles. In 2003, Pacino was commanding and pathetic and suitably reptilian as Roy Cohn in Mike Nichols’ HBO filming of Angels In America. The year before that, in Christopher Nolan’s Insomnia, Pacino was convincingly haunted and kind of jazzily weird in a role that he could easily have coasted through by deploying a few Pacino Tricks and relying on the fact that he naturally looks like someone who sleeps poorly. His performance in 1997's Donnie Brasco is as good as any he’s ever given, which means that one of the better Good Good Pacino performances and what is by my lights the best Good Bad Pacino performance—his turn in The Devil’s Advocate, about which there is [simultaneously leering and howling now] much more below—were in theaters in the same dang year.

Bad Good Pacino

This one is more complicated. Al Pacino is a really good actor, and as a general rule his performances are more good than they are bad. But what makes Good Good Pacino different from Bad Good Pacino is how he fits or doesn’t fit his performance into the films in which he’s appearing. Even when Pacino was at his zenith as a star in the early-middle 1970's, he mixed in some forgettable movies in which he played a horny-but-conflicted race-car driver; there are no clean getaways in a 50-year movie career, and that includes times when Pacino gave the performance that he wanted to give regardless of whether it belonged in the film or not.

There are a great number of films in which Bad Good Pacino enlivens various scenes without ever quite fitting into the broader enterprise. It’s in these films that we can see exactly how interested Pacino is and more importantly is not in the film. For instance, here is a good Al Pacino performance of a decent enough monologue from what is a mostly not-very-good movie. Bear in mind, as you watch it, that Pacino is supposed to be playing a NFL head coach, or anyway the head coach of a team in a professional football league that does not infringe on any copyrights. You are probably familiar with this scene:

And it’s a good scene! He does a good job. There is such a thing as Bad Bad Pacino, and that iteration of Al Pacino would’ve just BOOMED his way RIGHT THROUGH this MONOLOGUE. What we see, instead, is Pacino taking some decent enough language and bringing all the virtuosic tricks he has at his disposal to bear on it. He’s good enough at talking to make some moderately prosaic dialogue inspiring, and more remarkably he’s able to make it seem as if these words are occurring to him in that moment.

But that’s it, that’s where it ends. This is a performance, not just in this scene but throughout the film, that seems wildly unlike any coach that has ever existed in any sport. It’s Pacino giving a Pacino performance, right down to the fact that he appears to be wearing the clothes he’d be wearing out on the street, give or take a few scarves. Obviously you’re not looking for verisimilitude in an Oliver Stone movie; the man has been filming his ayahuasca burps for decades. Stone’s directing of actors, in recent years, has mostly been a matter of getting extremely close-up shots of hideous prosthetic teeth. The good news is that Pacino, when presented with all this, decided to give an actual performance, and hits the notes he aims to hit. The less-good news is that none of this has much to do with, or much benefits, the film around it. It’s Good, but that’s all it is.

(From what people tell me, this is also true of his turn in the Adam Sandler fart-and-wig opus Jack & Jill, but while I have reviewed Pacino’s work in that, I am absolutely not going to watch the whole thing and tell you for sure.)

But you see the point, by now: Good Pacino is good. But context matters, and Bad Good Pacino does not give a shit about that. Given how many weak movies he’s made, it makes sense that Pacino would occasionally just choose to do his thing, and at least “his thing” is good, in this case. There is an alternative.

Bad Bad Pacino

For optimum effect, please imagine that I’m duck-walking around in a billowing suit and screaming every third syllable as you read the following, please.

It is tough to say when Bad Pacino first appeared, but 1990's retrospectively inexplicable Dick Tracy is my guess. It’s an impossible movie, a bunch of Hollywood’s biggest male actors putting on extremely bright suits and playing grab-ass on expensive sets, interrupted periodically by Warren Beatty wolfishly ogling Madonna to the point where awooga sound effects would not be inappropriate. Pacino played Big Boy Caprice, the film’s main bad guy, and it is safe to say that he does not under-do it:

Which, given that he is playing a literal cartoon character, is a perfectly reasonable thing to do. What is stranger is that, like a Method actor stuck too deep in a role, Pacino has been weirdly prone to slipping into Big Boy Caprice in the years since, at moments that do not necessarily demand it. It’s not so much that Pacino makes strange actorly choices in performances like these, although a Bad Bad Pacino performance is full of [absolutely bellowing now] choices. It’s that the choices seem to be the result some sort of malfunctioning algorithm that dictates them to Pacino at random.

This can be fun to watch, admittedly, but it also resolves to watching a great actor roll out all his various virtuosic actor tricks, at max intensity, for reasons that are impossible to parse. There are times during Heat, which is probably the best film with a Bad Bad Pacino performance in it, when Pacino himself seems unsure what he’s doing, or why, and is surprised by it. This is the acting version of Steve Vai making some wow-I’m-surprised-at-this-crazy-riff face during a grandiose guitar solo:

And here he is wailing away before tossing the damn guitar into the crowd:

There’s no reason not to enjoy these performances, honestly. Not every actor is built with a whammy bar, and it’s not Pacino’s fault that he chooses to use his sometimes. It’s just that some of these performances are a lot more fun than others.

Good Bad Pacino

When he feels like it, Pacino can commit to and inhabit a character, and those performances are good. But when he does not feel like that, Pacino can also commit to just fucking blow it all up. This is, again, a choice, but when the Good Bad Pacino Firehose is at full blast it feels like mostly one big choice as opposed to a series of thoughtful smaller ones. If Pacino was only doing this now, the way that Robert De Niro is mostly just wandering through films looking like he needs a Maalox, it would be kind of a drag, if still a lot more fun to watch than the De Niro version.

But Pacino mostly holds his fire on the Good Bad Pacino performances, saving them for films in which what is required of him is not something human or even especially humanesque but instead something more like:

The Devil’s Advocate is, in retrospect, the sort of film that doesn’t get made anymore. Not in the sense that it’s kind of a religious thriller featuring a commanding central performance by the literal fucking devil using John Milton as a fucking alias, although there is that, but in the sense that it’s a total moonshot—a shameless genre movie in a genre that doesn’t exist, with a purely batshit concept, borrowing lustily and at random from the guiding tropes of a half-dozen different genres. It is, in other words, exactly the sort of film that doesn’t just deserve but demands a performance like Pacino’s.

This isn’t to say that it couldn’t have been roughly as interesting with a low-key and thoughtful performance in place of the one Pacino chose to give. But why would you want that, when you could have this instead?