When Cleveland was awarded the 1981 MLB All-Star Game, it was a city in dire need of a boost.

The previous decade, beginning with a fire on the Cuyahoga River in 1969, had battered the city that once billed itself as the “Best Location in the Nation.” In fact, on the day in 1979 the Plain Dealer announced Cleveland had been picked to host the All-Star Game, the story shared the front page with Mayor Dennis Kucinich testifying before the House Banking Committee about the city’s default; it was the first time an American city had defaulted on its loans since the Great Depression.

The All-Star Game wouldn’t fix any of that, but it would provide a showcase for a city that was trying to pick itself up off the canvas—and those showcases had been few and far between for a town that prided itself on its sports teams.

The Steelers had a virtual lock on the AFC Central Division throughout the 1970s, rendering the Browns also-rans. (The Browns did win the division in 1980, before losing to the Raiders in a playoff game that’s known for one thing: Red Right 88.) The Cavs had decamped to an outlying county, but they were spinning their wheels too (under the administration of Ted Stepien, who bought into the team in 1980 and ultimately became majority owner, things would get so bad that the NBA would actually pass rules to limit the effects of his ineptitude). An NHL team came and went in two years. And the Indians? Well, they were a bad team playing in front of empty seats. Between 1958 and 1970, the Tribe was perpetually linked to any city that didn’t yet have a major league team, with plans to move to Seattle, or even play “home” games in New Orleans. It was an era when a sellout crowd on Opening Day at cavernous Cleveland Stadium could account for as much as 10 percent of the team’s total yearly attendance.

“We were absolutely overjoyed to play host to the All-Star Game,” said Bob DiBiasio, who was then just starting out what would be a 40-year career in sports media relations—all but one of those years with the Indians. “The town was struggling a little, to say the least, and we were making a comeback and everybody in town rallied around the All-Star Game to put the spotlight on and show we were on the rebound.

“Then the strike hit, and everyone was deflated.”

On May 29, 1981—the same day that the Indians dropped a 5-2 home game to the Yankees, and the same day the city introduced its new ad campaign, “New York May Be the Big Apple, But Cleveland Is a Plum”—Major League Baseball players authorized a strike. Two weeks later—a month before the scheduled All-Star Game—the players walked out. For the first time in nine years, games would be lost because of a work stoppage. There would be no long-awaited All-Star Game.

“Cleveland was taking a bad rap in those days,” said Dale Kirk, the weekend assignment editor at WKYC, Cleveland’s NBC affiliate. “We felt cheated. We were supposed to have the All-Star Game, the big fanfare of the summer. We felt we had to do something to regain our pride.”

So a bunch of guys from Cleveland staged their own All-Star Game—with dice and card tables. At Cleveland Stadium.

Jon Halpern grew up playing Strat-O-Matic Baseball. Strat-O-Matic, which bills itself as the original fantasy sport, began with a tabletop game in 1961. Two years later, founder Hal Richman added cards representing each MLB player. It’s now available to play on computers, online or on mobile devices as an app. But whatever the medium, the basics of the game are the same: You pick the lineup and roll a total of three dice, using strategy and a maybe a little luck to try to win.

By 1978, there were Strat-O-Matic versions of football, basketball and hockey, but baseball was by far the most popular sport, outselling all the other sports combined.

“Strat-O-Matic was well-established by 1981,” said journalist Glenn Guzzo, author of Strat-O-Matic Fanatics, the definitive history of the company. “It had a spotty retail presence, but it had a good following among baseball fans, including some players and those who ended up in baseball front offices.”

Or broadcast studios. When the staff at WKYC was throwing around ideas for something to do in protest of the strike, Halpern, the producer for the weekend 11 p.m. newscast, came up with the idea of a Strat-O-Matic All-Star Game.

“It was clear [negotiations] were going nowhere,” said Jim Schaefer, weekend producer of the 6 p.m. newscast and Halpern’s roommate at the time. “When it looked like the strike was going to happen, it was his idea. We pitched it to the station, and we got the sports department involved.”

“It was our way of salvaging something and trying to have a little fun,” Kirk said.

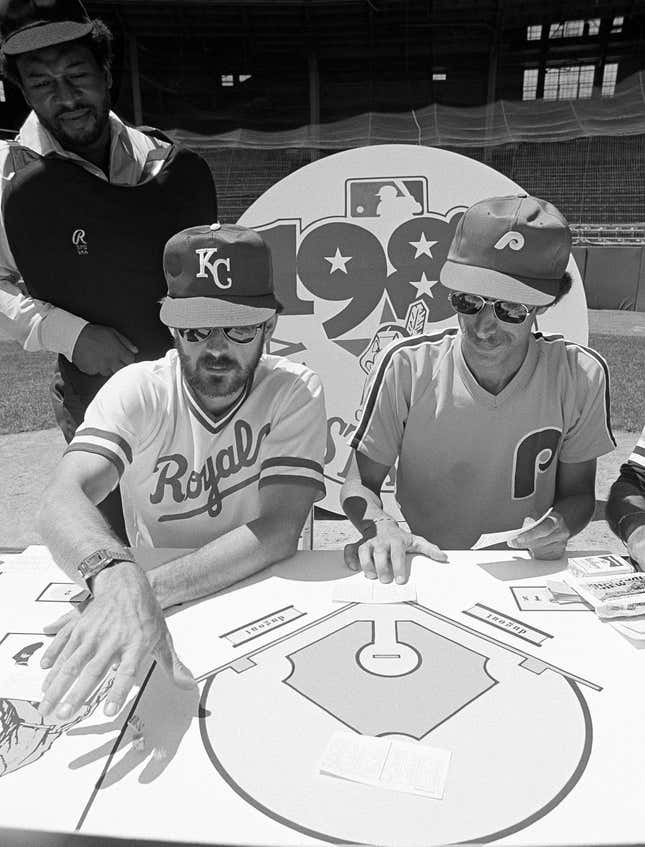

Halpern was a Phillies fan, and feeling pretty good about that, since his team was the defending World Series champs. He’d be thrilled to manage the National League team. Schaefer had grown up all around the Midwest, but he had taken to the Indians since coming to Cleveland in 1974 (and you really had to love the team to be a fan in those days). He’d skipper the AL.

Schaefer said that like ballplayers themselves, he and Halpern went into training. “We played about 25 games before the actual All-Star Game,” he said. “Jon was much more proficient at it than I was, but I’d followed baseball stats closely.”

And so, on July 14, the day the real All-Star Game would have been played, Cleveland threw its own. And even if it wasn’t a “real” baseball game, it had all the bells and whistles Cleveland fans had come to expect.

Halpern and Schaefer got Rocco Scotti to sing the national anthem. It wasn’t an official sporting event in Cleveland unless it led off with Scotti, a construction worker turned opera singer, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” He was a regular at Indians games, and sang at four other Major League ballparks, as well as the Football Hall of Fame inductions in Canton and the Knights of Columbus track meet. But his status to sing at the real All-Star Game had been in doubt. In the book Split Season: 1981, author Jeff Katz said Scotti wasn’t quite famous enough for Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. But he was famous enough for Halpern and Schaefer. His national anthem was accompanied by accordion, not an organ, prompting Franz Lidz to write in the next week’s Sports Illustrated, “This was the first All-Star Game that sounded like an Italian wedding.”

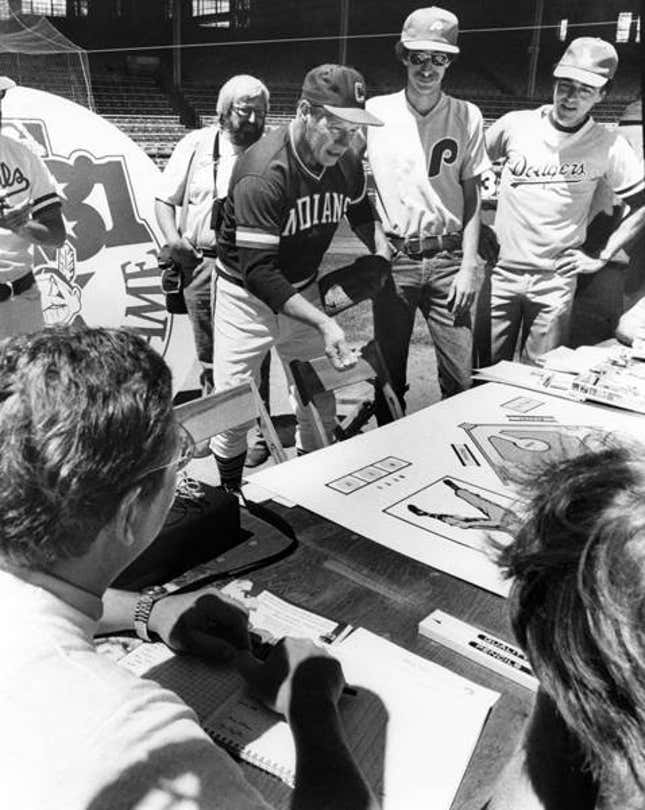

Bob Feller threw out the ceremonial first dice. “We had the idea we needed a celebrity and he was the obvious choice,” Schaefer said. “He was a trooper and always a loyal Indian.”

Feller was an Iowa native, but had made the Cleveland area his home following his Indians career. He was a regular on the rubber chicken circuit and signed so many autographs he once said a baseball without his autograph was worth more money because it was rarer. All they had to do to get him to the Strat-O-Matic game was ask.

“It was a delight to meet him,” Schaefer said. “He came into the locker room and started putting on a jockstrap and then he said, ‘Wait, I don’t need a jockstrap for this!’”

The game was at Cleveland Municipal Stadium—which rankled MLB officials. And they weren’t shy about voicing their displeasure.

“I got my ass chewed out by Major League Baseball for allowing that ‘game’ to happen,” DiBiasio said. (We spoke on the phone, and he made it a point to say he was putting air quotes around “game.”) “But I couldn’t do anything to stop it. They contacted Bob Feller on their own. They contacted Rocco Scotti on their own. I found out about a couple hours before the game!”

As the name indicates, Cleveland Municipal Stadium was owned by the city. But in 1973, Browns owner Art Modell formed the Cleveland Stadium Corp. to lease the stadium from the city and handle operations. Stadium Corp. was the Indians’ landlord—and quite frankly, gouged them. (It’s no coincidence that the Browns moved to Baltimore when Modell no longer had the Indians as a tenant.)

“They actually let us use the scoreboard and the PA system,” Schaefer said, noting that they were able to use the stadium for free. “WKYC was behind us on this, so we weren’t two random guys asking to use the stadium. We had some institutional weight behind us.”

Also on hand was the Baseball Bug, the Indians’ fuzzy mascot introduced a year earlier. The Bug, portrayed by Ron Chernek, then a graduate student at Cleveland State, was still making appearances on behalf of the team, so he wasn’t quite as idle as Indians players (the front of the sports section the day after the Strat-O-Matic game showed pitcher Wayne Garland pumping gas because he needed to make ends meet during the strike), but he didn’t have a lot going on.

“I probably would have gone anyway,” Chernek said. “It beat doing nothing.

“I was supposed to do my usual shtick. There were maybe 30 people in the stands, but they were into it. If you’re going to volunteer to be there, you’re probably going to be enthusiastic about it.”

The Plain Dealer’s Dan Coughlin, who was the game’s official scorer, said he counted 58 people in the stands—in a stadium that seated nearly 80,000. Kirk said it was “the first time I ever sat in the front row at Cleveland Stadium.”

The starting lineups were picked via fan calls to Sports Phone. In an era where not just results but live audio and video are at your fingertips, it seems almost medieval to recall a time when a dial-in line providing sports scores and information was regarded as cutting-edge. But that’s what Sports Phone did, and it was. With the MLB strike coming in the middle of the summer, Sports Phone had been hit just as hard as Cleveland was by the lack of games, and thousands of fans called in to vote.

[UPDATE, 02/22: While Strat-O-Matic Fanatics said Sports Phone votes were used to pick the lineups, Jim Schaefer told me they used the last released All-Star Game vote counts to select starters.]

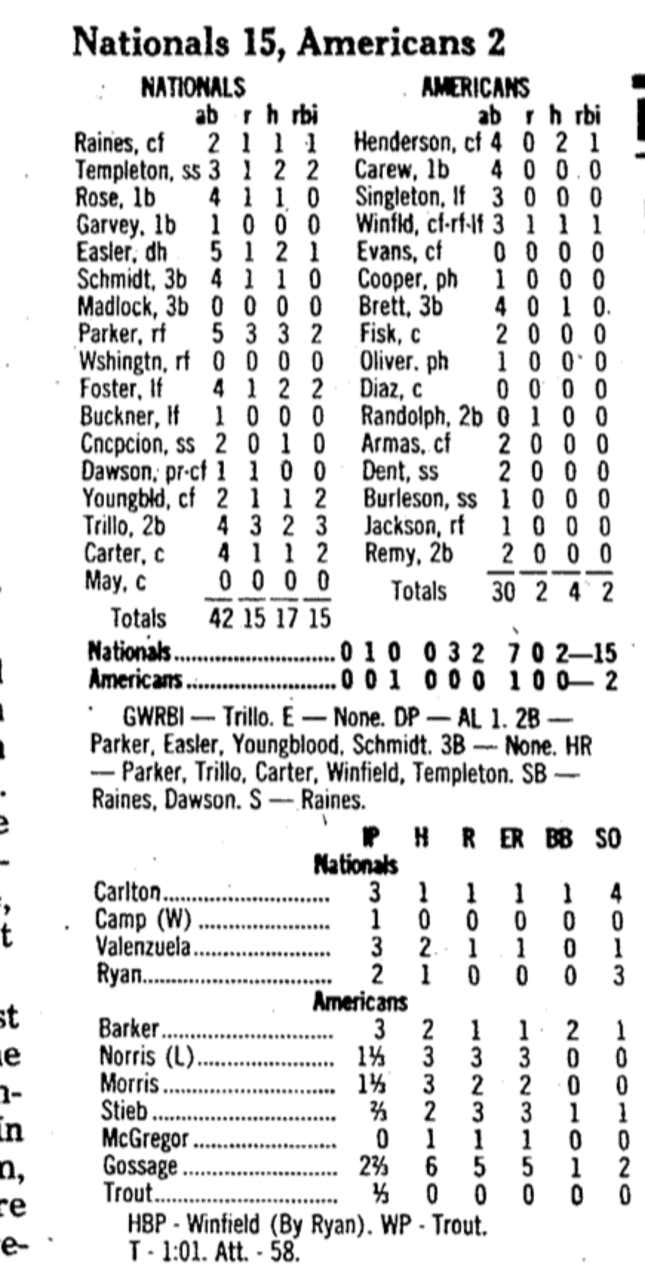

Large Lenny Barker, just two months removed from his perfect game at Cleveland Stadium, got the start for the American League team. Dave Parker got the National League on the board in the second inning with a home run off Barker, but the American League tied it up in the bottom of the third. The National League took the lead for good in the fifth, and blew the game open in the seventh, scoring seven runs on the way to a 15-2 rout.

“Except for the fact the managers used dice and cards instead of balls and players, the rest of the proceedings resembled most of the All-Star games of the last two decades—with the American League falling flat on its face,” wrote Thomas M. Burnett of United Press International.

After they left Cleveland Stadium, Kirk figured that was the end of it.

“We all went out and had some beers after that and had a good laugh over it,” he said.

One of the reasons the MLB All-Star game gets as much attention as it does is because there’s usually nothing else going on at the beginning of July. The NHL and NBA seasons are over. NFL training camp hasn’t started. There aren’t really any college sports.

Fact is, when a bunch of TV guys were coming up with the idea to play Strat-O-Matic Baseball at home plate at Cleveland Stadium, there were a lot of other journalists who were just as annoyed by the strike, and just as bored.

“We got a lot of coverage,” Schaefer said. “Sportswriters were looking for something to cover. It had a long wire story, and it made all the network news programs. CBS News covered it that night!”

“I was supposed to go on ‘Good Morning America,” Chernek recalled. “But I got bumped because of something going on in Northern Ireland. I still got to be on Nightline, though.”

WKYC’s coverage earned a local Emmy, Schaefer said. Alas, most of the footage, in those heady days of Betamax, appears lost to history.

Schaefer and Halpern had to make a trip to Cooperstown. The Baseball Hall of Fame wanted the board and cards from the game, and displayed it for the next couple years.

The game was also a boost for Strat-O-Matic itself. Richman was worried that fan resentment would hurt sales of the cards, but he estimated that the mock All-Star Game got him millions of dollars in free publicity. “It helped save the year for him,” Guzzo said.

On July 31, players and owners reached an agreement, and baseball would return. But what would happen to the All-Star Game? The 1982 game had already been awarded to Montreal, but the Expos seemed receptive to the idea of pushing back their game so Cleveland would get theirs. As it turned out, it wasn’t necessary.

“We felt the town would still generate the kind of revenue it was looking to generate from this type of event,” DiBiasio said.

The MLB All-Star Game—the real one—was played Aug. 9, the very first game back from the strike. It’s still the only All-Star Game to date played in August, and the only one on a Sunday. “Everyone who was there was glad to see baseball again,” Schaefer said.

Like the Strat-O-Matic game, the National League won. Dave Parker was the MVP of the Strat-O-Matic game, going 3-for-5, but Gary Carter took the honors in the real game (both Parker and Carter homered in the Strat-O-Matic and the real thing).

And if there was any fan resentment, it couldn’t be found on the lakefront in Cleveland. The 72,086 in attendance is still the largest-ever crowd for an All-Star Game.

A lot of the guys at WKYC moved on. Halpern died about 10 years ago, Schaefer said. Dale Kirk still lives in the Cleveland area, leaving briefly for Columbus before returning. He can be found playing trumpet in a local band, Shout!

Bob Feller died in 2010. Virtually up to the end, he could be found at Progressive Field, and his seat in the press box is a small shrine to him. Rocco Scotti died in 2015 at the age of 95.

Schaefer left for the Washington D.C. area, but he remains a Cleveland fan—as do his kids, who were all born in Cleveland. He and his son came back in 1993 for the Indians’ last weekend at Cleveland Stadium, and his son was offered a ticket to Game 7 of the 2016 World Series...the day before the game. Of course, he made the trip.

Bob DiBiasio was at that Game 7. He was also at the Game 7 in Miami in 1997. He was also at Cleveland Stadium in October 1993. DiBiasio’s the senior vice president of public affairs for the Indians. He’s seen a lot, but nothing quite like what he saw at Cleveland Stadium on the day the 1981 All-Star Game was supposed to be played

“I can’t imagine something like this will ever happen again,” he said. “You have to have the right scenario in place. The team has to be a tenant in the stadium, and that doesn’t happen in the truest sense.”

The Baseball Bug’s brief life lasted through the end of that season, when it was squashed and supplanted by Tom E. Hawk, the mascot of the radio station that carried Indians games. The Bug is now generally remembered as “one of the worst mascots in baseball history.”

Ron Chernek, who as the Baseball Bug had been formally protested by George Steinbrenner and polkaed with Steelers running back Rocky Bleier, was offered the chance to be Tom E. Hawk, but he’d graduated college and gotten a job, so he couldn’t do it. He’s now a lawyer in the Cleveland area. He’s got a bunch of pictures from his days as the Baseball Bug, and in most instances, he needs them as proof—but especially for the day he danced in front of a crowd of dozens at a Strat-O-Matic baseball game at Cleveland Stadium.

“People still don’t believe me that this really happened.”

Vince Guerrieri is an award-winning journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He likes Lake Erie perch sandwiches, Jim Traficant and long walks on the field at League Park. His website is vinceguerrieri.com, and you can follow him on Twitter @vinceguerrieri.