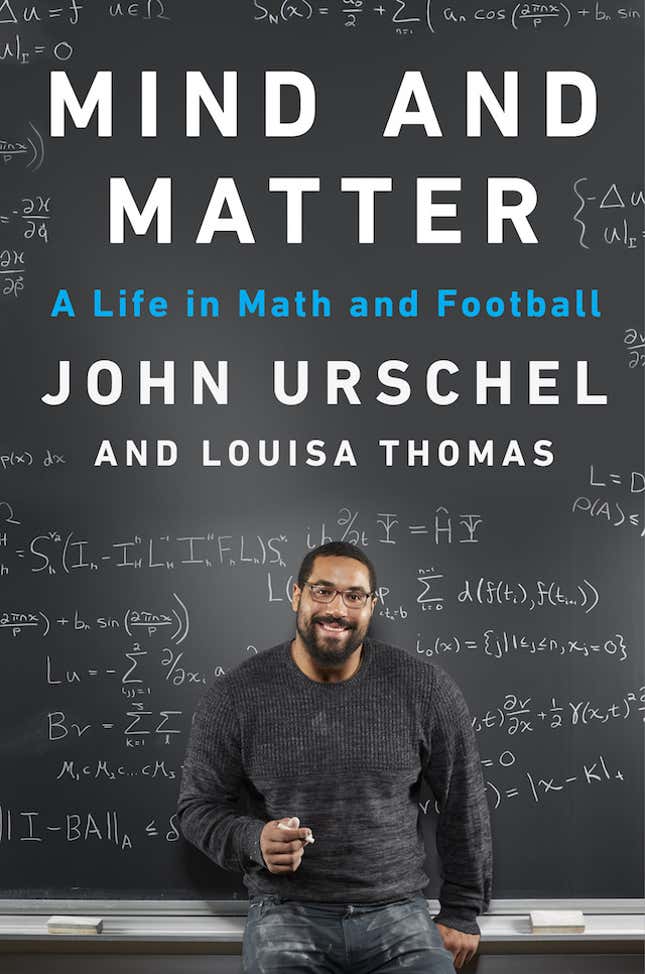

John Urschel spent three seasons as an offensive lineman for the Ravens. He’s also a candidate for a Ph.D. in mathematics at MIT—a pursuit he began in 2016, during his final season in the NFL. He’s also written a book, Mind and Matter: A Life in Math and Football, that’s being released today by Penguin Random House.

Deadspin recently spoke to Urschel by phone. What follows is a transcript of that conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Why write the book? Why now?

I’ve thought about sort of writing a math-type book for some time now. And that was originally what this was intended to be. But the more I talked with Penguin about it, the more Penguin asked for me to put more of myself into it. Just given that they thought it would make of my journey with mathematics more accessible. They thought, “No, John, you know you can’t just write about your journey with mathematics without talking about yourself holistically, and talking about football as well,” and so that’s how this thing sort of grew. I take no joy in writing about myself, but I really enjoy talking about mathematics, talking about my relationship with mathematics, and the beauty of math—and I hope that was conveyed in some way in this memoir. I have to say in my motivation for writing it, the motivation was not talking about football; it was not to tell everyone about myself. It was sort to try to show people the beauty of mathematics through my stories.

Football, though, was a big part of how you you know got to do a lot of the things you’ve wanted to do with mathematics.

Yeah, absolutely. [Football] was a huge part of my life, so it’s not something you can you can really ignore, I think, so it would be quite silly to try to simply talk about my relationship with math without talking about everything else going on in my life.

Louisa Thomas is your life partner, but she’s also your co-author on the book. She’s obviously a very accomplished writer and journalist. I’m curious about the process, then, in putting together a book like this with someone like her.

One thing that should be noted is that this book is a family affair. She’s the best writer I know, and I’m not just saying that because she’s my partner. The way we went about it was I recognized what she’s much better at than me, and she recognized what I’m much better at than her. Her main job, which she did a fantastic job of, was taking the things that I’m saying and making them sound better than they originally were. And my main responsibility was to tell the narrative, to get this out there. Also, Louisa knows nothing of math. All the math sections—if there’s even like a little typo in a math section, that was completely my fault.

I didn’t notice any. I think.

Okay. Good. [laughs]

You once wrote for The Players’ Tribune about how the expected points for two-point conversions is greater than for extra points, but you also touched on how risk-averse NFL coaches are. Despite that, do you think NFL teams should be going for two more frequently than they do?

Oh, Lord. Okay. Let me think about this for a second. So, this is good! First of all, this tells you where I’m at with my life. I remember myself writing something about two-point conversions versus one point, but I can’t remember the conclusion. So let me just go through it again.

I didn’t mean to put you on the spot.

No, no, no, you’re totally fine. I mean, you’re not putting me on the spot—like, a reasonable person would do this. Okay. If your two-point conversion rate is higher than, like, half the time of your one-point conversion rate, then probably I would say in most circumstances, you should go for two. But not in all circumstances.

When wouldn’t it be good?

Well, it depends on what the score is and how much time is left. It’s a nuanced conversation. These people who sort of say, like, “Oh, we’re just going to go for one point all the time unless it’s extremely clear we have to go for two”—they’re leaving something on the table. Because there’s these sort of gray areas where it’s not so clear, but the statistics tell you you’re a little better off going for two. And here, you know, maybe some risk aversion comes into play. But I’m going to tell you: The people who go for two and say they’re going to go for two all the time are perhaps even worse.

Really? Why is that?

Okay. Well, in the following sense. Everyone sort of goes for one; if you’re going for one all the time, except in these special circumstances where you’d have to be a fool to go for one, then you’re doing what you learned—you’re following the herd, in some sense. If you’re someone who goes for two all the time, you are consciously doing something different from everyone else, but just deciding that you’re just going to go for two all the time, even though in some circumstances, going for one might be the right play. And that’s even stupider—well, I shouldn’t say even stupider. That’s stupid. I understand the concept of, you know, this is how you learn to coach football, and you play traditionally—I understand this. But if you’re someone who says we go for two all the time, this is nonsense to me.

Yeah, there was a stretch a few years ago when the Steelers went for two pretty consistently, and then they failed to convert a bunch of times in one game and then more or less did away with that strategy.

It’s a little more interesting than most of the sort of analytic-type problems you face because it’s not so black and white. And the analysis that you have to do to figure out—okay, this is how much time is left, this is what the score is, how the game is likely to result in terms of number of scores, things like this. It’s still what I think is a little bit of interesting math.

In the book, you mentioned that at the combine, one team asked you to list all the things you could do with a paper clip. What was your answer?

Oh. Yeah. [long pause]

You kind of acknowledged that your academic smarts could have been perceived by teams as problematic, since they all expect football to dominate your life. And, as you wrote, you were obviously hyper-aware of any answers you gave at that time.

So, yes. I don’t remember, but I do recall that I answered the question honestly. It seemed like a reasonable question sort of testing your imagination.

How do you think questions like that apply to football, though?

I’m going to level with you. I have absolutely no clue. I mean ... Okay, first of all, if someone can’t list three things maybe this is a red flag, but this sounds more like the sort of question that you would sort of ask of a mathematician. If you’re a mathematician or you’re interviewing on Wall Street or something, that’s a reasonable question—an attempt to sort of test your imagination. Because in some fields—and mathematics being one of them—I think imagination is important. But in football, I have no clue what that’s doing there.

Now, with football analytics there are a lot of variables that are tough to isolate, and it can be tough to know exactly how teams are using the data they might have at their disposal. But are there any trends you’re noticing, or things you see that you think are especially forward-thinking right now?

Great question. First of all, you’re absolutely correct—it is tough to know what conscious decisions a football team is making. Well, at least what sort of more nuanced conscious decisions, because sample sizes are so small in the NFL. And it’s just really tough to tell. But I have to say, I haven’t really noticed anything, and perhaps I should admit that I haven’t actually watched pro football as a fan since I was at Penn State.

Ah. Okay.

When I was in the league, I would watch film, but I would never watch TV broadcasts. And just like when I played in the pros, I only watch college football. This is what interests me.

Did the Ravens share much about how they used their analytics with you as a player, or was it simply a matter of executing what the coaches told you to do?

Yeah, I was aware of some of the things they were doing. I was friends with the current head of sports analytics there, and the previous head. I was closer with the previous head. Yeah. We would discuss things sometimes.

I at least want to ask you about the Patriots. They’re so good at staying ahead of trends. They stockpile draft picks, they manipulate the comp pick system, and they’re very good at adapting within games, much like they did during the last Super Bowl. In the book, you discussed your 2014 playoff loss to the Pats, when you guys were up two touchdowns and Bill Belichick used what John Harbaugh thought was an illegal formation.

Yeah, I mean, if it’s not against the rules, it’s not illegal.

Right. But you presented that anecdote in the book by relating it to game theory, to the psychology of how Belichick threw you guys off your game, and how it’s important to use intuition in addition to numbers. I’m taking forever to ask my question but how crucial is a lot of that stuff to the Patriots’ ability to sustain so much of their success?

It seems to be quite important. I mean, okay, I have to admit that, like I said, I don’t follow the NFL extremely closely. But it seemed to me while I was playing that the Patriots were optimizing what they could do under the rules and what they could do from a strategic point of view in a way that other teams simply weren’t. And, okay, first of all, granted, the Patriots have Tom Brady. This is something we just need to keep in mind. An extremely strong quarterback is a premium in this league, but I think they’ve just done a fantastic job for such a long time in a league that encourages mean reversion.

To shift gears a little, you talk a bit about the risk of head trauma for football players. In the book, you even detailed your own experience with a concussion when you played. Looking back with a full understanding of the risks weighed against all the positives you experienced, would you play again?

Absolutely. No question. I absolutely loved my time playing. My favorite time playing football was playing football at Penn State. Playing college football at Penn State was such an amazing experience. And when I got to the league I came to realize that not only is the league sort of different from college football in many ways, but my experience in college football was very different than most of my teammates’ experiences in college football. At Penn State, we really had something special, and I didn’t realize this until after I left, but guys at other colleges were not as close as we were. And maybe this has a lot to do with the things we went through. [Ed. note: Urschel was at Penn State during the Jerry Sandusky scandal and its aftermath. He explains in the book what it was like to be a football player with no connection to the underlying crimes and institutional failures, while repeatedly taking care to note that he was not trying to compare his and his teammates’ experiences to whatever Sandusky’s victims have been through.] Me and all my teammates, these are my best friends in the world. It’s something special.

You had the opportunity to leave during the Sandusky scandal, to go to Stanford. Did the decision to stay bring you closer with your teammates?

Yeah. I mean, listen, thank God I stayed. Looking back, I can’t imagine what my life would be like if I left. That would have been probably one of the worst decisions of my life. And that wasn’t so obvious then, but it’s very obvious now.

Now, if you were to have a son would you let him play football?

Yeah. Yeah, I would, but not till high school. I have very mixed—okay, my feelings aren’t that mixed, but I’m not a fan of like Pop Warner, those sort of things. But I am a fan of youth flag football.

A lot of the research is trending in that direction, that it may be a safer alternative for before high school.

I mean, I’m going to level with you here. I don’t need to see research articles and double-blind studies to know that flag football is better for people than regular football, especially before you get to high school. It’s just my opinion. People love to talk about concussions these days. But the focus I think is really in the wrong area. There’s a lot of focus on pro football players, but I think there’s not nearly enough focus on youth football—very, very young kids without fully developed brains, often without proper coaching, without proper technique going at it with each other. Maybe my opinion is wrong, in the sense that it seems to me like the focus has really been on professional football, and sort of high-level football. Maybe it seems that way because I was in professional football, in high-level football, and this is all I see. But it seems to me like that has been more of the focus with respect to concussions and head injuries than say, kids who are, like, nine years old.

What do you make of football’s labor structure, the way the league treats its players?

It’s certainly different than some other leagues. It’s different than the NBA. I think this is largely due to a number of factors that don’t allow us to have a strong players’ union. One, careers are quite short. Two, there are large rosters. And three, we really lack a secondary league, a secondary market. I think all three of these things are serious barriers to improving that sort of situation from the players’ perspective.

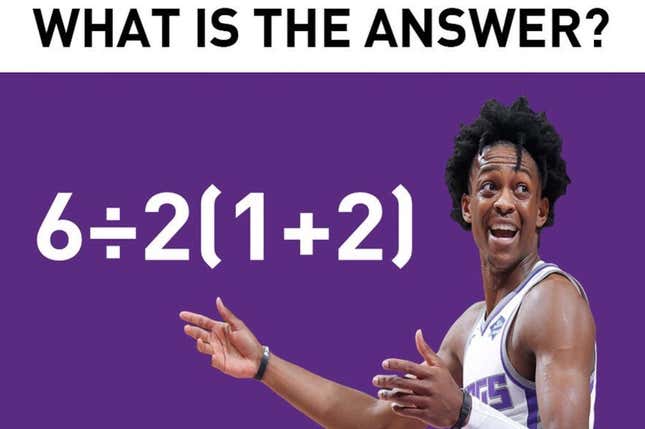

One last question. I don’t know if you were on the internet last week, but there was a dumb math problem that the Sacramento Kings put out on Twitter that was really a trick question. I don’t know if you’d seen it.

No, I haven’t.

Okay. They tweeted it and it became a discussion here among the staff at Deadspin, because we’re idiots. I’ll do my best to describe the equation, but it was six, division sign, two, and in parentheses two plus one, end parenthesis.

Yeah, first of all, I don’t know why the internet loves these. Two, I don’t know what this really has to do with math. I want you to know, like, never at MIT are we standing around the blackboard discussing, like, “No, this is the order of operations, no, that order of operations is right.” But, yeah. So you said six divided by two parentheses two plus one, right?

So the question is, is the answer nine, or is it one?

Yeah. You’ve got to do the parentheses first. Okay, so then you get six divided by two, times three. And then you just go left to right. Like, you don’t do multiplication before division; it’s just left to right. But I have to say, again, this argument is incredibly stupid, because it’s not arguing about math, it’s arguing about notation. Which is sort of, like, quite a silly thing because who decided this is the way the order is going to be?

Right. It really did launch a very stupid discussion among the staffers here. We even did a post about it, in fact, just to articulate how stupid it was. When I knew I was getting you on the phone, I had to ask you about it.

Oh, yeah. No, of course, no, that was funny. I’ve seen many of these. Many people have sent me such things, and, uh, yeah.