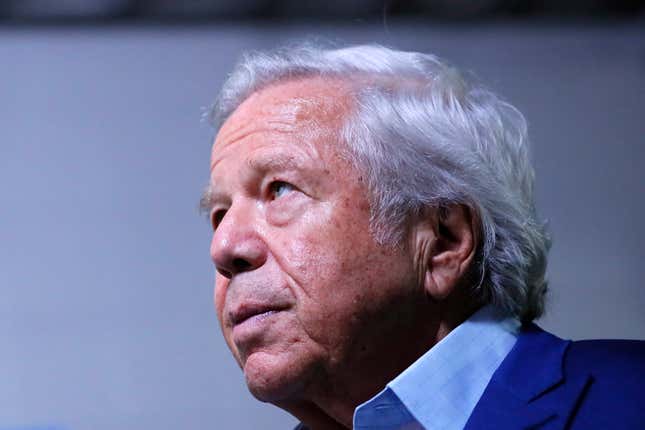

In the photos, Robert Kraft looks every part the billionaire—well-tailored suit, shock of white hair, deep tan, big grin. One of the most powerful men in American football has been seen in recent photos living the glamorous life at the West Hollywood launch party for rocker Jon Bon Jovi and son Jesse’s “premium Rosé,” sitting courtside at a Boston Celtics playoff game and a Boston Bruins Stanley Cup final game, walking the red carpet at the Profile in Courage Award, and posing at a gala for his son Dan’s nonprofit. It’s all handshakes and smiles, with no trace of the scandal, courtroom battles, and embarrassment of the nearly four months past.

Since March, Kraft has been deploying some of the most powerful defense lawyers in the country to misdemeanor court in Palm Beach County to fight two counts of solicitation. Police say Kraft went twice to a massage parlor accused of providing customers with hand jobs and blow jobs in return for payment. According to police in Jupiter, Florida, Kraft received two sex acts in exchange for $100 each, one on the day of the AFC Championship Game between Kraft’s New England Patriots and the Kansas City Chiefs.

So far, Kraft’s decision to turn down a plea deal and fight has paid off. Key video evidence in the case has been thrown out, as has evidence from the traffic stop used to identify Kraft, and the entire case seems poised to fall apart unless an appeals court decides to weigh in.

As the case works its way through the legal system, it seems quite possible that Kraft’s appeal will set a precedent regarding the use of search warrants authorizing secret video surveillance, known as “sneak and peeks,” further building Kraft’s self-branding as a criminal-justice reformer. And it is all happening without Kraft ever setting foot inside a courtroom.

Because of Kraft, what would have been a police blotter entry in local newspapers has made international headlines. The fates of the women named as being at the center of the prostitution sting, meanwhile, have received far less attention, particularly since their status in the eyes of law enforcement and the press changed from human trafficking victims or human traffickers to willing sex workers. But all of the women, including those who allegedly gave Kraft hand jobs, face many more charges than the men who were their clients.

While the prospect of stricter punishments for the women follows a strict reading of the law, it also reinforces the massive power imbalance between the sex workers trying to eke out a living and their male clients. While Kraft can afford the best defense lawyers in the country without blinking an eye, the women arrested have had their comparatively meager savings frozen. And unlike the johns, they face not only criminal charges, but the loss of their livelihood. Meanwhile, their cases have been subject to a heightened level of scrutiny due to the involvement of one very famous man.

“I think that but for Kraft, the case wouldn’t have been covered by the media,” said Paul Petruzzi, one of the lawyers for Lei Wang, who managed the massage parlor Kraft visited. “The attention on Kraft infected this case from top to bottom. Kraft has spent huge amounts of money [on lawyers] and the service list on Lei Wang is greater than people charged [with] murder.”

A review of court testimony as well as police and state health department records, shows a clear pattern of missteps that led to such a public unraveling. It also shows how unevenly the impacts of those mistakes have been divided between the most powerful man charged and previously unknown sex workers. It looks very likely that Kraft will defeat the charges and—if he succeeds in getting video evidence of his alleged hand jobs suppressed—his life will go on as normal. For the sex workers, who have lost their jobs, their homes, and their reputations, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

The investigation that became State of Florida v. Robert Kraft wasn’t supposed to be about Kraft at all. It began when the Martin County Sheriff’s Office (MCSO) received a tip from a Florida Department of Health inspector, Karen Herzog, about possible prostitution Bridges Day Spa in Stuart. While investigating that business, the MCSO tipped off law enforcement in nearby Jupiter about possible prostitution at the Orchids of Asia Day Spa, a massage parlor in an otherwise anonymous strip mall. In their application for a search warrant, Jupiter police say very little about the details of that tip: “Detectives from the Martin County Sheriff’s Office advised they were working several cases of prostitution and human trafficking at Asian Massage Parlors in their county. During the course of their investigation, information was gained that there was a similar business in the Town of Jupiter.”

Jupiter police opened an investigation in October, according to an application for a search warrant, starting with Detective Andrew Sharp searching online records for who owned the business and taking screenshots of reviews for the parlor on rubmaps.com. Sharp surveilled Orchids of Asia for a week. In his application, Sharp mostly notes the spa’s long hours and predominantly male clientele. Then Sharp asked a Florida Department of Health inspector to do a “routine inspection of the business.”

Hours after the same inspector, Herzog, completed her inspection, Sharp and another detective searched Orchids of Asia’s trash. They found what they described as torn-up customer logs and napkins that “appeared to be covered in seminal fluid” (later confirmed by testing), Sharp wrote. It was evidence of possible prostitution, but hardly proof of human trafficking.

That’s where Sharp made use of Herzog’s inspection. In his application for a search warrant, Sharp wrote that Herzog believed “female employees were living there as there were two rooms with beds, including sheets and pillows.” The application also stated that Herzog found a “refrigerator filled with food and condiments” and medicine. Later in court, Herzog testified that the food in the refrigerator struck her as excessive “because I have two young boys, one is a teenager, at home and it was more food than we have in our refrigerator.”

But at no point does Herzog’s state inspection report say any of that. It’s two pages, dated Nov. 14, and makes no mention of medicine, beds, or excessive food. She attached two photos of a refrigerator that would not look out of place in any workplace kitchen. She doesn’t mention the possibility of trafficking or prostitution or even any criminal activities.

The massage parlor is dinged on just one issue: A “no” for safe and sanitary massage equipment because of “some tables showing wear and tear,” the report says. To the question of if the location was being used as a principle domicile, Herzog wrote “N/A.” (Herzog would later say under oath that she wrote “N/A” because “I was concerned for my safety,” though she did not elaborate.)

“The evidence of trafficking was supposedly the refrigerator and condiments,” said Katie Phang, another attorney for Wang. “We have refrigerators with condiments at my law firm, then I must be running a brothel from the law firm?”

A second trash pull a day later found more torn-up logs and more napkins with seminal fluid, Sharp wrote in his warrant application. Next, Sharp conducted traffic stops with four men after they left Orchids of Asia. According to the warrant application, all four told officers that they paid for and got hand jobs along with their massage.

(Jupiter police and the Palm Beach State Attorney’s Office declined to comment for this story because the case is still open. The Florida Department of Health did not respond to multiple calls and emails seeking comment.)

At this point, according to the documents made public in the case, Sharp had not documented any solid evidence of human trafficking. That posed a problem, because the search warrant he requested isn’t a traditional one, in which officers must appear during daytime hours, knock on the door, and at some point show the warrant. Instead, Sharp asked for a delayed-notice warrant, also known as a “sneak-and-peek,” that would allow him to plant cameras inside massage rooms. Historically, such warrants were next to impossible to obtain except in the most extreme circumstances. Then the Patriot Act was passed.

“Before 9/11, before such things as sneak-and-peek warrants, [traditional search warrants were] how law enforcement conducted themselves for over 200 years, and it’s not like we had a shortage of people being detained or a shortage of evidence against people committing crimes,” University of Miami law professor and former federal public defender Celeste Higgins said. “This had been a tried and true way of being able to search.”

After 9/11, then-president George W. Bush signed the Patriot Act, which among other provisions allowed law enforcement to use delayed-notice warrants to fight terrorism, with plans to sunset the act in a few years. When that deadline came in 2005, Congress decided to make permanent a few parts of the Patriot Act, including allowing sneak-and-peeks in any situation where there is reasonable cause to believe that “providing immediate notification of the execution of the warrant may have an adverse result.” With such broad language, the practice began to flourish.

In 2014, the Electronic Frontier Foundation found that the single biggest reason delayed-notice warrants were requested in federal courts were for drug investigations, and that a negligible percentage involved terrorism. The most recent numbers, from 2017, show the same pattern—17,200, or 78 percent of all requests, were for drugs, while just 122 were for terrorism. The same data set shows that 592 warrants requested for offenses classified as “sex,” but it doesn’t go into more details about what kinds of crimes.

“This was supposed to be an extraordinary tool for extraordinary circumstances,” Nova Southeastern University law professor Bob Jarvis said, but now “it’s become commonplace.”

Still, even with the explicit authorization of Congress, sneak-and-peek warrants aren’t supposed to be used for just any crime. Because it involves many potential violations of the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure, the tool is supposed to be saved for major crimes, not more routine prosecutions like prostitution. “Going into your space and checking out your home should be difficult,” Higgins said. “It should have extra hurdles. It should take extra steps. Because it’s your privacy, your house, your business.”

That’s why it was so important for police to make their case about something more than misdemeanor prostitution.

In Sharp’s warrant application, he doesn’t say explicitly that the Jupiter case is about human trafficking, but he does bring up nearby Martin County, writing that the neighboring jurisdiction was “working several cases of prostitution and human trafficking in their county.” After alluding to an unnamed first-degree felony, Sharp explains that in his expert opinion, no other law enforcement tool will work. Interviewing the women is not a good option, Sharp wrote, because women in Asian massage parlors “are very reluctant to speak with law enforcement out of fear and oftentimes will be untruthful if interviewed.”

That might be the stereotype of Asian women, but it’s not true of the women who worked there, said Tama Kudman, the lawyer for Orchids of Asia owner Hua Zhang. (In the application for the search warrant on Bridge Day Spa in Martin County, Detective Michael Fenton referred to a spa as part of the “standard Asian model,” which he described as “a place to operate prostitution under the guise of a massage therapy business.”)

Kudman said she believes law enforcement put the women at risk by relying on racial caricatures.

Law enforcement made “a pronouncement that most of these women in their experience are not citizens and don’t have residency cards, and so they’re afraid to talk to law enforcement, because they’re afraid of being deported,” Kudman said. “Well, at [Orchids of Asia], every [masseuse] was not only either a resident or a citizen, but they were in their 30s and 40s. These were not children. These were women who held multiple massage and cosmetology licenses. [The truth] couldn’t have been further from the stereotype that they were trying to paint when this case first occurred.”

Sharp also wrote that a typical warrant would be impossible because undercover officers would have to pay for hand jobs, breaking the law to investigate the breaking of the law. Higgins doesn’t buy that logic, pointing out that police have investigated drug cases using undercover officers and informants and without consuming the drugs.

“Approach one of the women who you think are being trafficked or go in for a massage and approach one of them and say, ‘Listen, if you are not in a safe space to talk to me, I want to help you. Work with me, and I will try to get you out of here,’” she said. “There is any other number of alternatives and methods they could have used.”

But the police’s objections to more standard tactics were enough for a judge. Palm Beach Circuit Judge Howard Coates signed off on installing cameras as part of a sneak-and-peek warrant on Jan. 15. He said police could record for five days.

Two days later, on Jan. 17, Jupiter police conducted what they called a “tactical rouse” to install the cameras. A nearby pizzeria owner told the New York Times he suspected it happened the night police evacuated the massage parlor due to a “suspicious package and a possible bomb threat.” Joseph Bompartito said he thought it was odd that the officers that night evacuated only the massage parlor, not the other businesses in the strip mall.

Police placed cameras in Orchids of Asia’s lobby, where money was exchanged, and in the massage rooms. They did not put them in kitchens or elsewhere because those areas were “non-criminal in nature,” according to the warrant, signed by Coates.

Phang said basic surveillance would have shown that the women weren’t being trafficked. Instead, she said, it would have shown all of the masseuses opening the spa door with their own keys.

According to police records, the cameras recorded from Jan. 18 to Jan. 22. Kraft visited the parlor twice, on Jan. 19 and Jan. 20, the second visit happening hours before he flew to Kansas City for the AFC Championship Game.

Each time, Kraft arrived in a Bentley with a driver, who waited while Kraft was inside. On Jan. 19, police wrote in a supplemental report that the driver “begins smoking a cigar outside” while waiting for Kraft. Inside, each time, Kraft went into the massage room, undressed, and laid down on a massage table, where one of the women was seen manipulating Kraft’s penis, then wiping it down with a towel. On the second visit, police wrote that “it appeared she was performing oral sex on him,” although the oral sex detail wasn’t included in the later probable cause affidavit. Both times, according to police records, Kraft paid cash and gave the women hugs.

Police executed a traffic stop on Kraft’s Bentley after the first visit. An officer stopped the Bentley for a “traffic violation,” issued a warning for going 55 mph in a 45 mph zone, and identified Kraft, who is described as “very polite and respectful during the whole process” in court records, even asking the officer if he was a Miami Dolphins fan. During the stop, according to the filing, Kraft explained that he was the owner of the New England Patriots and had to get to Kansas City the next day, and even showed a Super Bowl ring.

Despite the traffic stop, Kraft went back to the spa the next day. There, according to police, he paid for another sex act.

On Jan. 31, Herzog completed another inspection report for Orchids of Asia. All of her written answers were consistent with the ones she recorded in November except for the domicile question, which she changed to “Yes=D”. Herzog didn’t write any explanation for the change. The new report also was not signed by a representative of the spa, instead reading, “Representative: Not Available to Sign.”

In her court testimony, Herzog said she had been communicating with detectives between her initial visit and the new report, but said that she made the change based on a request from her manager, not the police.

A few weeks later, similar investigations across Florida’s Treasure Coast concluded, and dozens of arrests were announced. At press conference after press conference, law enforcement in Indian River and Martin counties referred to the women involved as “girls” and painted them as victims of human trafficking schemes—but victims who had no choice but to cooperate with law enforcement. Martin County Sheriff William Snyder said one woman was describing how she was forced into sex trafficking, until her own defense lawyer showed up and asked to speak with her. The woman, no longer being treated like a victim, has been charged with racketeering, money laundering, deriving support from the proceeds of prostitution, operating a house of prostitution, permitting prostitution, and engaging in prostitution.

Meanwhile, the rumor mill started speculating about Robert Kraft. The whispers were persistent enough that questions came up at a Feb. 21 press conference in Indian River County, about 60 miles north from Jupiter, about someone connected to the NFL getting caught in that county’s investigation.

The guessing game ended the next day, when Jupiter police announced they were charging Kraft and about two dozen other men with solicitation of prostitution. At the press conference, Jupiter police chief Daniel Kerr said he was concerned about possible human trafficking.

A few days later, Palm Beach County State Attorney Dave Aronberg announced at his own press conference that his office would proceed with the charges. Aronberg went further than Kerr, calling human trafficking “evil in our midst.” “Human trafficking is the business of stealing someone’s freedom for profit,” he said. “It can happen anywhere, including the peaceful community of Jupiter, Florida. We need to do better to get victims to speak up. If we would treat victims as victims and not criminals, we’d get them to speak out.”

Nobody was charged with human trafficking, but Aronberg said at the press conference that such charges were still a possibility. Yet attempts by law enforcement to get the women to label themselves as human trafficking victims were unsuccessful. One video, obtained by the Associated Press, shows a masseuse enduring a 4-hour interrogation by Fenton and others, where they try unsuccessfully to convince her she was a trafficking victim.

Just a few months after a Times headline declared “The Monsters Are the Men: Inside a Thriving Sex Trafficking Trade in Florida,” prosecutors said in court they do not expect to bring any trafficking charges in the Jupiter case.

Zhang’s attorney says that law enforcement implied, without evidence, that Zhang—a 58-year-old Chinese-born grandmother who has a master’s degree—was operating a human trafficking ring alongside the 39-year-old manager, Wang. Wang and Zhang were each charged with 26 misdemeanor counts of soliciting another to commit prostitution, one felony count of deriving support from the proceeds of prostitution, one misdemeanor count of renting a space to be used for prostitution, and one misdemeanor count of maintaining a house of prostitution. Zhang’s total bond initially was set at $278,000 and Wang’s at $256,000, although they were later reduced enough that both were released on $5,000 bail.

The Martin County Sheriff’s Office is attempting to seize Zhang’s home, as well as the homes of her son and cousin, her lawyer said, because prosecutors alleged that they were all part of the massage parlor business. In fact, Kudman said, Zhang occasionally stayed at her cousin’s home to babysit. Zhang spent a few days in jail before being released.

Wang spent six weeks in jail, where her lawyer said fellow inmates pointed at her picture on the TV and asked, “Is that you?” Wang’s home was targeted for forfeiture, and detectives seized Wang’s sister’s jewelry from the safe in her home, as well as passports for Wang’s sister and nephew, according to Phang. The jewelry and passports still haven’t been returned.

“Do I think it’s overcharged? The answer is yes,” Phang said. “Do I think it’s overcharged because Kraft is involved? I don’t know.”

In April, two more masseuses were arrested: Shen Mingbi, 58, who massaged Kraft, and Lei Chen, 43, who did not. Both were charged with deriving proceeds from prostitution, a felony, as well as eight misdemeanor counts of offering to commit prostitution. Mingbi had $43,800 seized from her safety deposit box, and police froze $2,900 from Chen’s bank accounts, according to police records.

Because Mingbi allegedly gave a hand job to one of the wealthiest men in America, Mingbi’s (and Chen’s) fates became entwined with Kraft’s. Their faces were splashed across websites alongside the two other women who were charged. Details of the sexual acts they performed on Kraft became fodder for late-night comedy shows.

All four women have pleaded not guilty. They have each surrendered their passports, and they are banned from working in massage or spa establishments. They each face up to 15 years in prison for the felony charge of deriving support from the proceeds of prostitution. Zhang’s and Wang’s 27 misdemeanor charges each come with an additional maximum penalty of a year in jail. Zhang and Wang face 28 misdemeanor charges, 27 of which come with an additional maximum penalty of a year in jail.

The 25 men arrested for soliciting sex at Orchids of Asia, meanwhile, were charged with misdemeanors. Their bonds were set at $500. Prosecutors offered the men a plea deal. If they admitted they would have been found guilty if the case had gone to trial, they’d receive no jail time. Instead, the men would have to pay a $5,000 fine, perform 100 hours of community service, take a course on prostitution, and undergo testing for sexually transmitted infections.

Kraft didn’t spend a day in jail. He was charged but never arrested (he wasn’t in Florida, and charged with a non-extraditable offense), and he immediately hired himself a very good and very expensive defense team. His lawyers included William Burck, a “Washington superlawyer” who also happens to love the Patriots, and Alex Spiro, a favorite lawyer of Jay-Z whose clients also have included Naomi Osaka, Thabo Sefolosha, Matt Barnes, and Aaron Hernandez. Kraft put out a press release in which he said he had “extraordinary respect for women” and that he was “truly sorry” but did not admit to doing anything illegal. He has yet to set foot in a Palm Beach County courtroom.

“I don’t know if they’re out to get my client because of the Robert Kraft angle, but I think by default we’re all collateral damage,” said Wang’s lawyer, Katie Phang. “I think even the johns get that much more scrutiny and that much more attention.”

Kraft’s legal team reportedly turned down an offer of a plea deal, instead contesting the charges by focusing on on the constitutionality of the search warrant and the lack of human trafficking charges.

They got their victory about a month later, at a lengthy March hearing about Kraft’s request for the court to prevent the video from being released under Florida’s public-records law. During the arguments, questions arose about whether the masseuses who worked at the spa were considered victims. Prosecutor Greg Kridos spoke up to offer some answers, telling the court: “There is no human trafficking that arises out of this investigation.” Kridos did try to couch that, saying the case when it first arose “had all the appearances of human trafficking” but, he said, after going through dozens of boxes of evidence, authorities had “no evidence to charge anybody with human trafficking.”

Kraft’s attorneys hammered at that point a month later at a days-long hearing to debate the constitutionality of the warrants and if the evidence gathered under them should be allowed in court. They argued that Kraft had a reasonable right to privacy inside the rooms, that the warrants never should have been issued given the lack of evidence of human trafficking, and that law enforcement didn’t take enough precautions to avoid recording people who were there just to get a massage. They spent hours going back and forth with Herzog on the details of her inspection. They spent a huge part of one day going line-by-line over police documents with Sharp.

Jupiter officers insisted they didn’t watch innocent people who just got a massage. They determined this, Sharp said, by checking to see what a man did with his underwear. Boxers on meant they were getting a massage. Off meant they were getting a hand job.

The underwear system was not enough to satisfy County Judge Leonard Hanser. Like judges in the other counties, he found the warrant wasn’t good enough. In his ruling, Hanser took issue with how little was done to avoid surveilling activities not related to crimes. The warrant didn’t discuss how to minimize watching and recording women, who weren’t suspected of paying for sex acts, and “more than one woman had a significant portion of her Spa time viewed by a detective-monitor and the entirety of her spa time recorded and placed in Jupiter Police Department records,” Hanser wrote. Recordings of men who didn’t receive sex acts showed another “serious flaw in the search warrant,” the ruling said. And no written standards were crafted for the detective-monitors, who “were simply left to their own standards and devices to satisfy the minimization requirement.”

The issue also has resulted in a separate civil lawsuit filed in federal court, which alleges that the recordings of people receiving legal massages violated their Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure. The latest version of the lawsuit alleges that at least 31 people were recorded while they were undressed and getting a massage. Sharp, Aronberg, and the town of Jupiter all filed responses saying the lawsuit should be dismissed, arguing that no constitutional rights were violated. Aronberg also asserts he has prosecutorial immunity, while Sharp says he has qualified immunity as a police officer. Jupiter argues that any violations of privacy were minor and not due to a specific town policy.

But for now, neither the evidence gleaned using the warrant—the video—nor the traffic stop used to identify Kraft can be used in court. Without those, the case against Kraft appears to be over. Judges in other counties threw out the video evidence in their jurisdictions too, and the videos also have been tossed from the cases involving the women. For now, any hopes for the state winning the fight for the video evidence, and likely the Kraft case itself, rests with Florida’s Fourth District Court of Appeals, which has been asked by prosecutors to review Hanser’s decision. From there, it could be appealed to the Florida Supreme Court.

Even when a case dissolves, it causes collateral damage. The men caught in the stings—the ones not named Robert Kraft—had their names and photos blasted across the internet. Two men were falsely accused; one of them said he thought about suicide. Unlike Kraft, many of them will not have highly paid PR professionals to shield them with press releases. They can’t charitably donate their way back into good graces. They can’t smooth things over with Super Bowl rings.

The women who were arrested, meanwhile, have been treated as criminals. They have had mugshots taken, served time in jail, and lost their jobs, their property, and their reputations. Even having their charges dropped won’t restore any of that.

As for Kraft? A few years from now, this will be little more than another thread of his narrative—a hurdle he overcame, a challenge to his impeccable character, a patch of darkness before he returned to the light. Perhaps Kraft will say it inspired him to further his work on criminal-justice reform, call it a teachable moment. When you’re rich and powerful, anything can be turned into a positive.

“When you start using slogans like human sex trafficker, prostitute, john, these [terms] have a lasting effect on the people that they’re used against,” Kudman said. “And we should really reserve [them] for people who’ve been proven guilty of those things. And our state attorneys and our sheriffs have to be more careful with their allegations before they destroy people’s lives.”