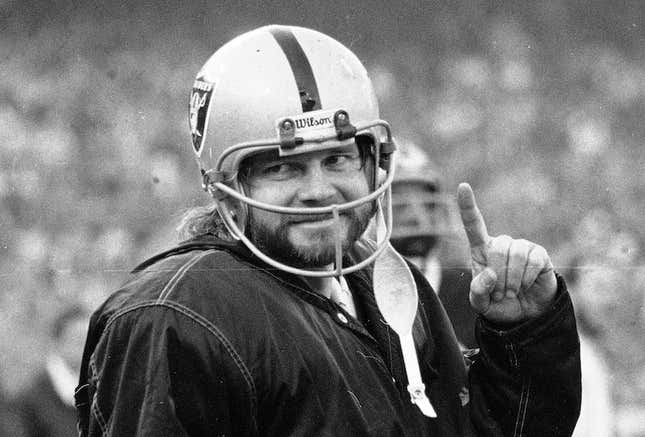

Ken Stabler, the late Hall of Fame quarterback, suffered from CTE and Alzheimer’s before his death; not even the NFL or its lawyers dispute that. Yet Stabler’s family will not collect any money from the NFL’s class-action concussion settlement, which has proven to be a disaster for hundreds of former players and their grieving families.

Stabler was diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in February 2016, seven months after his death at age 69 from complications related to colon cancer—the exact sort of situation the concussion settlement was meant to serve. Yet Stabler’s settlement claim was denied three times—twice as part of the claims and appeal process, and once and for all by the federal judge overseeing the settlement. The outcome of Stabler’s claim was first discovered in court papers by the indefatigable Sheilla Dingus, who runs a newly formed non-profit called Advocacy for Fairness in Sports.

“I guess in some weird, kind of crazy way, we can close the book, you know?” Kim Bush, Stabler’s partner for the last 16 years of his life, told me. “At least now you know definitively, okay, everybody has screwed him that can screw him. Let him rest in peace, put it behind us, and move on.”

Years before the settlement was finalized, Bush said, Stabler had signed on to the class-action against the NFL as a way of lending his name to the cause. Thousands of former players—most without Stabler’s prestige and Hall of Fame credentials—sought compensation from the league for its denial and manipulation of the science of head trauma. The NFL wound up settling with the class members as part of a mass tort, but the claims process has proved to be vexing for many.

According to Bush, and to Stabler’s eldest daughter from a previous marriage, Kendra Stabler Moyes, Stabler exhibited some classic signs of cognitive decline in his later years: repeating himself, getting lost in familiar places, difficulties navigating intersections with four-way stop signs while driving, sensitivities to sounds as simple as listening to music on long car rides or the clanging of dishes and pots in the kitchen.

“His head just thundered,” Bush told me. “I could just look into those beautiful blue eyes and I knew what was going on. He typically would look at me some days and just pull his head back, bounce it against his recliner, and go bang-bang-bang, and just say, ‘It never stops.’ And he clenched his teeth so badly that he broke a bridge in his mouth.”

Bush also described to me, in heartbreaking detail, how she remembered “every morning hearing him ... consciously make the effort to plant his feet a certain way to get out of bed so that the pain didn’t shoot through his body because his knees were so shot.”

Still, Stabler’s settlement claim was always something of a long shot, based on the way the settlement was crafted. CTE can only be diagnosed posthumously, and Stabler had agreed to donate his brain to researchers at Boston University after his death. Even though the BU team found he had Stage 3 CTE—“moderately severe disease,” as Dr. Ann McKee, the BU researcher who conducted the exam, described her findings at the time to the New York Times—his date of death fell just outside the nine-month window for which death with CTE would qualify for payment.

The settlement is clear that only players who died between July 7, 2014, and April 22, 2015, are eligible for a monetary award for death with CTE. Stabler died on July 8, 2015—a little less than three months after that window closed. As a result, his lawyers did not seek a claim based on death with CTE, but rather on a posthumous diagnosis of Alzheimer’s as a result of the BU team’s report, which indicated “a clinical history of progressive impaired memory and cognitive function, and pathological Alzheimer’s changes in the brain.” After an initial denial from the claims administrator last September, the Stabler estate appealed the following month.

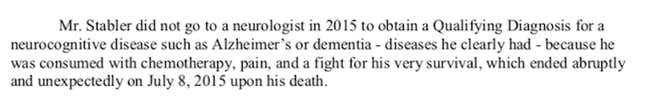

In that appeal, Stabler’s lawyers noted that Stabler had been diagnosed with colon cancer in February 2015, which they said prevented him from seeing a physician who could pinpoint his declining brain functionality while he was still alive:

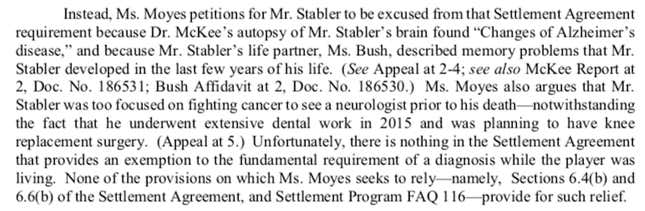

In response, the NFL hit back aggressively. The league’s lawyers drilled down on the fact that the settlement requires an Alzheimer’s diagnosis be made while the player is living. The league also doubted the Stabler estate’s contention that he was too busy fighting cancer to see a neurologist because Stabler had seen a dentist in June 2015—never mind that it was to repair the teeth he had been clenching on account of severe headaches:

The NFL conceded that the settlement empowers the claims administrator with the “discretion to review and decide” whether to grant exceptions, while adding that such leeway is “intended to apply to scenarios where documentation may be lacking but there was a diagnosis of the retired player while he was living.” The league also stated in a footnote that had the claims administrator excused any lack of a diagnosis without its consent, it would have constituted a breach of the settlement. In other words, the league was determined to fight any consideration of the unique circumstances surrounding Stabler’s claim.

Stabler’s appeal was denied in December, which prompted another appeal and additional opposition from the NFL. That appeal was finally denied June 13 by Senior Judge Anita B. Brody of the U.S. Eastern District of Pennsylvania, who cited the posthumous Alzheimer’s diagnosis as “insufficient,” according to the plain language of the settlement agreement.

This would be the same Judge Brody who remains convinced the settlement has been a smashing success, even though hundreds of claims are being appealed, stuck in audit, or denied despite seeming to meet the qualifying criteria. When Judge Brody has been inclined to listen to objections to the settlement’s parameters, it’s been to hear the NFL’s and even lead class counsel Christopher Seeger’s allegations of fraud against the players. In May, Judge Brody approved a new set of physicians’ guidelines that other plaintiffs’ lawyers say will make it even more difficult for players to get compensated. And just before Memorial Day, Judge Brody fired the other co-lead class counsels, leaving Seeger entirely in command—even as multiple plaintiffs’ attorneys remain frustrated that he has not been adversarial enough toward the league on behalf of ailing players and their families.

Tuesday afternoon, Seeger sent an email to members of the settlement class that was forwarded along to me. That email, in part, said (bolded emphasis is mine):

I do, however, want to take this opportunity to alert you about some essential aspects of the application submission process that will have an impact on your receiving an award if you are eligible. All the information you provide in your claim package must be absolutely complete and accurate. This includes the Claim Form, medical records, third-party affidavits, and information you provide to medical professionals. Remember that many of the awards are very, very substantial and you must assume that the NFL is doing its own research to check the validity of the information you submit, including any statements you make to your Diagnosing Physician about your daily activities, such as driving or employment. To avoid delay in the processing of your claim as well as possible denial of your claim, again, the information you provide must be complete and accurate.

The circumstances that took down Stabler’s claim, which boil down to the exact wording of the agreement, are not unlike what has kept the family of former Steelers center Mike Webster from getting compensated. Webster was the first former NFL player found to have CTE, but he died in 2002, and players who died before Jan. 1, 2006, aren’t included in the settlement. Last year, the New York Times noted that Seeger had written in court papers in 2015 that “[h]ad the plaintiffs not secured this provision, claimants on behalf of all deceased class members would have had to show that their claims were timely.”

Stabler’s daughter told me her dad’s claim was less about the money than about some kind of recognition from the NFL for the sacrifice that was made.

“I mean, yeah, compensation would be nice, but the point is, for them just to not acknowledge and kind of push these guys to the side, [by] making them jump through hoops and making it so difficult to get any sort of compensation,” Stabler Moyes said. “I just think it’s really, really unfair.”

Bush, Stabler’s partner, said she still loves football despite what she knows and what she’s seen. She said she plans to attend two Raiders games this fall, though those trips will be more about seeing old friends.

“I feel like a complete hypocrite about it,” she told me. “And yet at the same time I guess I’m willing to be hypocritical for the people that I love and care about.

“It’s just preposterous that that he was not awarded a part of that. The whole freaking league was built on the back of those guys, who are the pioneers of the league. There is damn proof of what he endured and what his brain took for playing the game, and it’s just almost like a slap in the face. I just think it’s so unfair to his memory, to his contributions to the game, and to all the guys out there.”