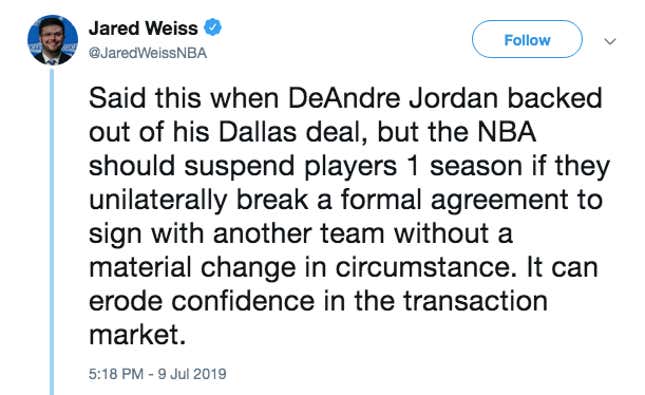

Here is some weapons-grade stoogery, from The Athletic’s Jared Weiss:

That’s in reference to the developing Marcus Morris Mess. If you haven’t been following, a recap: Back on July 6, Morris, an unrestricted free agent, reportedly agreed on a two-year, $20 million deal (with a player option for that second year) with the San Antonio Spurs. Then, yesterday, in light of news that the New York Knicks were backing out of an agreement to a two-year, $21 million deal with free agent Reggie Bullock, and thus would have more money to spend under the league’s salary cap, Morris reportedly reconsidered his options; it now appears he intends to withdraw from his agreement with the Spurs in favor of a one-year deal with the Knicks. The apparent rationale is that either deal would allow him to re-enter free-agency next summer, but the Knicks can offer him a much larger salary between now and then, and that’s an acceptable trade-off for giving up the insurance policy represented by that optional second year.

This appears to have messed things up for San Antonio. According to all the available reporting, the assumption that Morris was a done deal is what prompted the Spurs to trade forward Dāvis Bertāns to the Washington Wizards as part of the wheeling and dealing that enabled the team to sign yet another free-agent forward, DeMarre Carroll. If the organization had not been operating under the assumption that it was on the hook to pay Morris, it might have just signed Carroll straight up, without the need to clear cap space by trading Bertāns. Now it doesn’t have Bertāns, and it doesn’t have Morris, and the pool of possible free-agent replacements for either of them got pretty shallow during the four days its braintrust thought it had Morris.

That’s a tough break for the Spurs, one of the stablest and most widely admired shops in all of American professional sports, and particularly so while it’s still operating under the long, dark shadow of its unscheduled breakup with former presumptive franchise cornerstone Kawhi Leonard. Leonard, you’ll recall, sat out virtually the entire 2017–18 season, reportedly over dissatisfaction with how the organization handled his leg injuries, then forced his way out of town via trade the following summer, then won a ring and a Finals MVP award the very next season. So you can imagine that another player unexpectedly withdrawing a previous agreement to play for the team, leaving it suddenly shorthanded and without many obvious avenues for replacing him... well, it might smart a little extra.

But it’s very telling that to this point the media (and professional dogwhistler) handwringing over the broached sanctity of the noble “agreement” (and that The Athletic doofus up there isn’t the only one doing it, or doing it publicly; even ESPN’s Adrian Wojnarowski sloppily used the word “committed” to refer to Morris’s agreement with the Spurs) has focused on Morris’s situation, and not on, say, Bullock’s. Let’s revisit that.

Bullock, a 28-year-old wing who spent last season with the Pistons and then the Lakers, had an agreement in place with the Knicks by the end of the day on July 1, nine days ago, for two years and $21 million (with a team option for that second season). Now, because of an unspecified issue apparently related to his health—Woj calls it “an emerging situation”—the Knicks have withdrawn from that. The organization is “reworking the terms down to a lower financial commitment,” again according to Woj, because that suits the organization better, and because the organization has the leverage to do so.

I bet Reggie Bullock would have liked for that initial agreement to have functioned as a binding and enforceable commitment! He’s going to lose many millions of dollars because it wasn’t one. I wonder if he made any plans or purchases, in the nine days between the time the Knicks organization agreed to pay him $21 million over the next two years and the time it made the unilateral decision that, actually, it would prefer to pay him a small fraction of that. So far as I can tell, nobody at The Athletic or anywhere else has called for the Knicks organization to be banned from the NBA for a year over this.

Believe it or not, the NBA actually does have a mechanism in place to make a formal, binding, enforceable version of the handshake agreement between a player and an organization. That’d be “a contract.” Both parties sign it, and then they have to abide by its terms until it expires. If a player backs out of it—like, for example, by withdrawing unilaterally from his agreement to play for the team—he can even be suspended. Presumably this would satisfy even Jared Weiss’s desire to see the players brought to heel. The Spurs and Marcus Morris, like the Knicks and Reggie Bullock, simply hadn’t signed one yet. And until they did, neither party had any contractual obligation to the other.

Who can guess why they hadn’t gotten around to it? NBA player contracts, like any others in major pro sports, can be fantastically complex legal documents; presumably it might take a while to draw one up and get the parties together to review and sign on all the various lines in it. It’s nothing new for lots of business to get done in the interval between a publicized agreement and the actual signing of the documents, based in part on the presumption that the terms of that agreement are in place. But if, on Sunday evening, some unforeseen hiccup in the CBA had suddenly made it possible for the Spurs to sign Joel Embiid into the cap space they’d set aside for Morris’s contract, you can be sure they were not going to tell him, “Sorry, Joel, we’ve already made an informal agreement to pay that money to Marcus Morris.”

More to the point, if that did happen, the Spurs would get pilloried for it. An artifact of modern basketball coverage, a vocation now more than ever largely done by aspirational dweebs all but nakedly auditioning for front-office jobs in the league, is that all smart analysis must assume the priors of general managers; the players, in this framework, are abstract fungible assets and damn well better act like it. When the Knicks snatch years and millions out of their previously agreed-upon deal with a mysteriously compromised player like a dickhead father-in-law performatively retracting dollar bills from the tip each time his water glass gets empty, that’s anodyne basketball business; if any part of it comes in for criticism, it’s the team not having done its due diligence in the first place. When Marcus Morris backs out of an unconsummated agreement with one team in favor of a better deal from another, that’s A Violation Of The Sanctity Of Uh Confidence In Uh The Uh “Transaction Market” Or Whatever.

Along these same lines: The only reason the Spurs had to sacrifice Bertāns to afford their agreed-upon deal with Morris in the first place is because of a salary cap that the owners themselves continually insist upon. Was the existence of the salary cap, and the kind of hard, binary choices it forces upon front offices, a problem for the various Transaction Market Respecters when the Spurs were unilaterally deciding to ship Dāvis Bertāns from the NBA’s best organization to one of its very worst, 1,600 miles away, to make room for some other guy they liked better? Ultimately the criticism of Morris boils down to “This guy allowed a system designed and routinely deployed to screw players out of money and autonomy to screw a team, for once, and is a uniquely bad guy for it.”

In every relevant respect Morris’s decision is just as sensible as the Knicks’. More importantly, it’s every bit as square with the rules of the league, which up to now rightly have treated only contracts like contracts, and non-contractual agreements like exactly the non-binding nothings they are. Morris just happens not to be making that decision from the seat of institutional power in the sport. In the reaction to that, in the ludicrous call for players to be punished for seeking the best deal in the absence of one as in all the various simpatico qualming about the supposedly new horror of independent and mobile players who like the idea of getting to pick where they live and work, you can see the contours of exactly on whose behalf a whole lot of NBA reporters and analysts do their jobs—informally anyway, and at least for now without a contract.