Baseball giveth, and baseball taketh away. In these perilous times when every little moment is a referendum on whether the game will survive until Christmas, and every act of untrammeled joy comes with two asterisks that scream, “Yeah, but they’ll screw it up because it’s baseball and only old people who will die soon care.” When you spend all your time looking inward and not liking the view, you’re bound to wallow in your own pitiable angst.

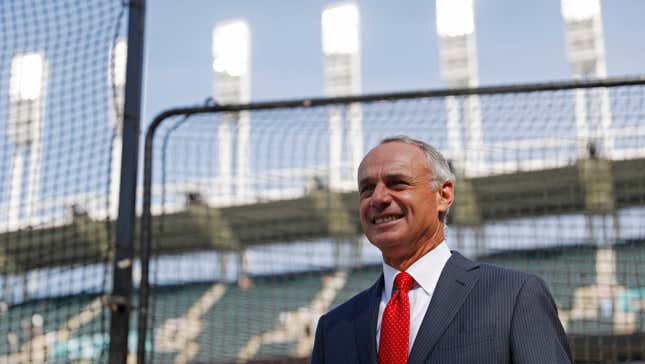

Which is why, after the brief but pleasing vibes of Monday’s Home Run Derby, Tuesday landed with a knee to the head. Bud Selig’s freshly whitewashed autobiography was roundly savaged for his “Barry Bonds Made Me Sad Because I Was Powerless To Stop His Reign Of Terror” excerpt and his brazenly self-serving fiction of the PED era in general, and current commissioner Rob Manfred bleated out of all four sides of his face about the construction and aerodynamics of the ball, saying that fans like the new home run binge while the owners aren’t nearly so enamored because attendance is down roughly nine percent from its last consistent rise in 2012 and ratings remains problematic, which kind of says fans aren’t all that hot for the home run after all.

Oh, and there’s still player-shaming about why they’re not as first-name-only popular as their basketball counterparts, as the Boston Globe’s Julian McWilliams pointed out in referencing the not-household-namey Mookie Betts. Evidently, Betts isn’t doing as many in-house ads as some of the folks in the home office would like, or some such equivalent nonsense.

But while everyone agrees that baseball is gripped in this self-swallowing malaise, nobody has a clue how to explain why this is, let alone why it doesn’t necessarily have to be. This brings us back to the one skill a commissioner should possess and which Manfred doesn’t seem to have at all—making the whole endeavor seem worthwhile.

Commissioners by and large aren’t all that powerful; they are essentially servants to the cabal of billionaires who pay them, and woe betide he or she who strays too far from the pack. Their general effect is largely stylistic rather than epoch-changing. People tend to think that because they have the title that they’re the ones to complain to, which is of course exactly what the owners want and why they pay such outsized salaries to their commissioners. Human shields shouldn’t come cheap, after all.

But there is value in the job if one wants to find it and draft behind and beside it. One of Adam Silver’s chief contributions to the NBA is to emit the sense that being part of the industry is just plain fun, and that whatever problems arise can be ameliorated by stealing here and there from the European soccer model, and applying a little group-think even if that group is just, ick, media. I mean, coach’s challenges are hardly a new thing; soccer across the world has long profited from the fan’s general urge to put down a quid or two on the odd match; an end-of-season tournament for the last playoff spot is merely the Brit idea of making the third-through-sixth-best teams in one level play for the last promotion spot to the league above. Silver stops short of suggesting full relegation because he knows his owners have paid too much money to get into the big show to get kicked out, and there is no evidence that either the G-League or the ACC would accept the Knicks.

Then again, Silver looks like the conciliator he is. He has a habit of leading with “Well, you may have a point there, but let me share with you why I think you might not,” which is a whole lot more palatable than Manfred’s disingenuously pugnacious, “The ball is different but not really, and it isn’t our fault because all we do is buy the things and quality control isn’t our concern, plus Mike Trout is being a deliberate buzzkill.”

To be fair, or as close as I will ever come to it, many of baseball’s issues are well beyond easy fixes. It is the game of history at a time when history is little-valued. It is a game that defies the notion that time is short and precious by disregarding it as a principal framework. It has lurched from too little math and science to almost too much math and science at the cost of enjoying the art of playing. It plays persistently for the short dollar while ignoring the long view. Over the last three decades it has thrown over old statistics for new ones, which is okay as far as it goes, while allowing both old schoolers and new schoolers to shout contemptuously at each other rather than appreciate their shared experiences. This rather makes the generational lure of passing the sport down the line less worthwhile for everyone involved; I mean, who doesn’t get all warm and huggy about a dinnertime argument about wins against win probabilities, other than everyone ever?

In short, there seems to be nobody who can articulate why the game can be just plain fun without degenerating into a tedious argument about bat-flips. There seems to be nobody who will say the game has intrinsic value that transcends the current downturn in measurable interest, and nobody who doesn’t make the game about the ratings and turnstiles alone, as though they aren’t fans but marketing executives, who as we all know rank somewhere between wolverines and four-slice toasters on the evolutionary chart.

It’s as if everyone wants to disparage the future of the game while forgetting why the present is worthwhile. It isn’t about Mike Trout the generational player as much as it about Mike Trout the reluctant commercial tool. Baseball is suddenly less a pleasant way to kill some tavern time than it is a rolling argument about nothing, and like watching an endless loop of the two Cubs fans who carried a brawl past security’s ability to arrest them, it loses its magic quickly.

And that’s where a commissioner comes in, and where Manfred so far hasn’t. Baseball (players, executives, media, et al.) has always had a cultural default about alternate ideas and behaviors by dismissively calling them “horseshit,” and then either walking away in contempt or responding to any further discussion on said topic by repeating the epithet. Manfred’s job, whether he knows it or not, is to slowly but perceptively eradicate that tic. He is currently 5,000-1 against.

Example: Silver’s midseason tournament concept is nearly as loopy an idea as Tampa owner Stuart Sternberg’s idea for time-sharing the Rays with Montreal, but because Silver throws out a lot of ideas (shortening the season without doing the owners’ financial math is always a favorite of his), he wasn’t crushed nearly so much for posing it. Manfred could have encouraged an informal discussion among his national media thinkers on the concept of Les Rays without taking a side, just in the interests of talking about something new. He could have acknowledged baseball’s unpaid debt to Montreal, even though it means criticizing his predecessor. He could have even showed up in a sleeveless Reds jersey to explain the difference between his arms and Derek Dietrich’s. Anything to look like he wants to bat around ideas about the game he allegedly loves.

Instead, he operates in permanent shields-up mode. He rigidly defends a status quo under attack from the indifference of a younger generation he has no idea how to reach. He says he knows nothing about the new snooker-ball consistency baseballs that have helped change the sport in a way that at least for the moment has not roused the customers to visible signs of approval. And encourages the notion he himself spawned that his best players are deliberate obstructionists who are ruining the one idea he is sure can save the game, the sport and the business: centralized marketing.

Two points should be made here. One, centralized marketing is the answer one uses for fixing a problem when that person has no other ideas. Marketing is the equivalent of saying, “Well, tell the lie a little better then,” and we as a nation are already neck-deep in that particular experience.

And two, while we are loath to judge people by their looks given our own considerable aesthetic shortcomings, Manfred looks like an angry undertaker watching his only hearse being repo’d. He givers the impression that he would get less enjoyment talking about the baseballs with Justin Verlander than he would from turning his dog on him.

But that second item does not disqualify Manfred from doing the one job he can’t front off on his owners, or the history-denying man he replaced—how to change baseball’s view of itself, including his own. He has to discover and demonstrate why baseball can be fun to watch and talk about and absorb without referencing demographic charts or marketing trends or equipment manipulation or player shaming. He has to start showing baseball has a future that isn’t just financial but social and cultural. He has to start acting like he’s got a great job instead of acting like he’s got a well-paying job.

Or he can do what he’s doing, collect checks for shaking his fist at invisible enemies and then retire and write a badly received book about all the fun other people ruined while he was hard at work looking like he passing a kidney stone the size of a schnauzer’s head. In other words, he has almost no chance of instigating such a sweeping reconsideration, but he should try his damnedest anyway if for no better reason than avoiding a future reading Bud Selig’s book reviews with his name written over Bud’s.

Ray Ratto is working on his doctoral thesis, tentatively entitled, “How To Hate What You Like: The Next Big Idea In Shameless Careerism.”