This year’s release of the Green Bay Packers’ financials is a bit more revealing than usual. The disclosures include what’s by now become a standard glimpse into the mammoth annual growth of the NFL’s national TV revenues; the NFL has been raking in assloads of money for years, and there’s still no sign of a slowdown. But the truly revelatory stuff is what’s sitting on the other side of the ledger, where the Packers’ spending on players and on the concussion settlement has eaten into a substantial portion of their profits. Still, some context is in order.

The Packers are owned by a publicly held corporate nonprofit, which means they’re required each year to make a portion of their books public. Though the information is largely unique to the Packers, its release does provide as good a look as any at some of the NFL’s overall finances for the fiscal year that ended March 31.

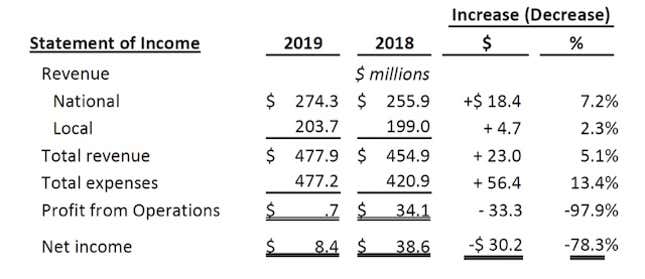

Let’s have a look at some numbers the Packers recently released:

That national revenue figure of $274.3 million tells us that every single team brought in that much money mostly from its television contracts, without having to play a down—that the league hoovered up a total of $8.8 billion from the TV networks alone.* Those numbers represent an increase of 7.2 percent from the previous year, and a jump of 21 percent from just four years ago. The NFL, as ever, is doing just fine. (Update: The Packers also have nearly $400 million in a corporate reserve fund. They’re doing just fine, too.)

But check out those expenses. They went up $56.4 million from the previous year, or 13.4 percent—a pretty sizable jump that left the Packers with earnings of $8.4 million, or a profit margin of just 1.8 percent. And as Daniel Kaplan of The Athletic noted, the Packers’ operating profit was only $724,000. Team president Mark Murphy attributed that increase in expenses to “some irregular” factors: some big-money free agent signings, plus the market-rate contract signed last summer by quarterback Aaron Rodgers. Via the team’s website, Murphy said player signings and the salary cap’s 5.6 percent hike accounted for $30 million of that $56.4 million increase in expenses. Payouts to account for the coaching change from Mike McCarthy to Matt LaFleur and to the NFL’s concussion settlement also factored in, according to Murphy.

A closer look at some of what the Packers did in the past year bears out that they indeed did some atypical spending. Rodgers’ deal included $78.7 million fully guaranteed at signing: a $57.5 million signing bonus plus $21.2 million in roster bonuses. Per league rules, all of that fully guaranteed money had to be immediately placed into escrow. Counting Rodgers’s $1.1 million base salary and a $500,000 workout bonus for 2018, the Packers had to part with $80.3 million for Rodgers in the past year, on a deal with a max value of $134 million.

Then, this spring, GM Brian Gutekunst broke with the Packers’ usual M.O. by being aggressive in free agency. Gutekunst committed substantial full guarantees to outside linebackers Za’Darius Smith ($20 million) and Preston Smith ($16 million); safety Adrian Amos ($12 million); and right guard Billy Turner ($9 million). Including Rodgers’s outlay, that’s $137.3 million the Packers had to cough up on just five players during the 2018-19 fiscal year.

Green Bay’s exact share of the concussion settlement is a bit harder to pin down. The team has not yet released its actual annual report, though it is expected to do so at its annual shareholders’ meeting on Wednesday. (Even then, of course, it’s likely that report won’t include detailed line items.) Some rough math, based on reports published by the settlement’s claims administrator, shows that as of April 2, 2018, some $150 million in claims had been paid out. By April 1 of this year, that figure was at $466 million. That’s a difference of $316 million, or $9.9 million per franchise, though it’s still not known when teams had to start contributing to the settlement fund, or how much they had to pay out during the last fiscal year. And in 2016, as Kaplan wrote for Sports Business Journal, the league’s 32 franchises began tapping a supplemental shared-revenue pool to pay for the settlement, to keep teams from having to pay too much out-of-pocket toward the settlement. Which only muddies the waters a bit more.

Still, it’s significant that Murphy would even mention the settlement as a substantial expense for the Packers: The NFL, through its lawyers, has been working diligently to squeeze claimants to minimize the league’s exposure from the settlement, which is uncapped. The league is also locked in a years-long legal battle with its insurance companies over who has to pay for the settlement. At the same time, the actuarial forecast for the settlement severely underestimated how many ailing players are out there who might file claims. On her blog, Advocacy for Fairness in Sports, Sheilla Dingus broke down just how substantial this undercount has turned out to be in the first 2½ years of what’s supposed to be a 65-year settlement.

In this light, it’s hard not to view Murphy’s inclusion of settlement payments on his list of the Packers’ “unique atypical financial expenses” as a backdoor way of acknowledging the NFL’s fight to limit its financial liability to former players and families who are suffering from the effects of repetitive head trauma.

“It was a unique year,” Murphy said. “We had some irregular expenses that affected our financial performance, but we’re still in a strong financial position.”

* A previous version of this sentence incorrectly stated that the NFL’s network TV contracts account for all of its national revenue.