It can be difficult to remember given that he routinely appears on television with toilet paper on the soles of both his shoes and at least one of his hands stuck in a big jug of peanut butter, but Donald Trump’s opening position in all things is that he has never been wrong. He has been wronged, and is in fact wronged constantly—by terrible nasty TV actresses and fake cable news anchors and the other antagonists he’s collected over a lifetime of nonstop blowsy public feuding. But that is just the price he pays for always being right and never being afraid to speak out on whatever he has just seen on television. He carries that weight lightly, give or take the fact that he whines about it constantly. There is an entire cable television network devoted to telling this story over and over again, and every day Trump parks his ass in front of it and watches embalmed-looking septuagenarian newsreader types talk about how correct he is and heatedly demand apologies on his behalf, for hours on end. It’s the treatment that he has always believed he deserves.

In a narrow sense, it would be easier for Trump to get away with his ambitious never-been-wrong gambit if he had ever bothered to learn anything about anything or simply opted not to talk about things he didn’t know about. But in the broader and Trumpier sense, it’s actually far simpler the other way around, and not just because he has always relied on a rotating crew of servile factotums to clean up his messes for him. A jarring number of professional political analyst types still persist in seeing some sort of strategy in this, which is both their job and self-evidently ridiculous. There is no deft feinting or tactical distraction involved when Trump returns from a trip abroad and says something like “no one ever knew that there even was such a thing as France, but that’s something that I’ve been seeing and we’re going to look into it.” He is not constructing a Reality Distortion Field or subtly signaling to his base. He just forgot there was a France and therefore just assumed there wasn’t one.

The issue here is not that Trump doesn’t believe in things like truth and untruth; he absolutely believes that some things are true and other things are false, but what makes them true or false to him is grounded entirely in how he feels about them. Once a belief is lodged in the sodden Nerf of his brain it becomes true to him, and remains that way forever. These things tend, if anything, to become more true over time, or at least become larger. There is probably some latent impulse from his days as a real estate huckster that powers this—in the same way that he once added floors to the oafish towers he developed, he now adds years or billions to the oafish tales he tells from the front of his trade war with China. It also cannot be ruled out that the guy just likes saying large numbers. When Trump authors one of his really avant-garde falsehoods, it’s this impulse that’s generally behind it. He just likes things to be big, if possible “much bigger many say than anything that we’ve ever seen” but always and everywhere as big as he can get away with making them.

And then, eventually, even bigger than that. This was a problem last week, when Trump took one of his favorite parts of the presidency—the constitutionally enumerated power to tell everyone about the weather, and how large it looks like it might be—too far. Hurricane Dorian, which is indeed big and terrible, was moving towards the southeastern United States at the time, and the forecast called for moderate-to-large amounts of destruction in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Trump evidently found this insufficient, and so he added Alabama, which abuts an entirely different body of water and is on the other side of Florida from the storm, to his list of states that could be threatened by the storm. The National Weather Service rebutted this assertion, in no uncertain terms, twenty minutes later. You already know that this wasn’t going to be the end of it. We are still a long way from the end of it.

He got upset about it online on Monday.

And then he just kept getting upset about it:

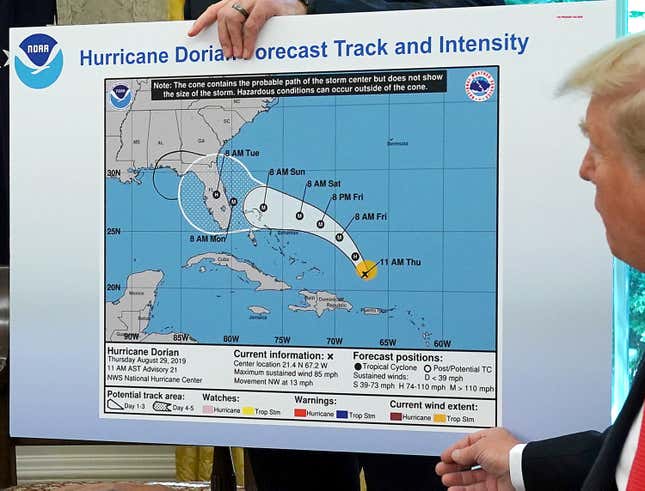

On Wednesday, days after Dorian had flattened wide stretches of the Bahamas, veered back out to sea, and then turned back towards the Carolinas, Trump invited the assembled media into the Oval Office, to show them a map of the storm’s course that a staffer had printed and matted for him. The image is obviously different from the one that the White House showed the public last week from a similar President Trump Points At A Map And Says “We’re Seeing It And It’s Unbelievable” press availability, most notably because someone, it’s hard to say who it might be, just kind of used a Sharpie to draw a second, poignantly misplaced testicle onto the phalloid shape of Dorian’s ultraviolent progress. In doing this, Trump or someone else who is also quite obviously Donald Trump simply corrected the National Hurricane Center’s forecast, which called for the hurricane’s track to pass hundreds of miles east of the Alabama border so that it more closely comported with his Executive Forecast.

Trump, when asked whether someone had drawn that improbable adjunct ball on the map with a marker, Presidentially said “I don’t know” three times in a row; White House spokesperson Hogan Gidley did not elaborate on that statement beyond saying that the media noticing the mark “would be hilarious if it weren’t so sad.” The real news, Gidley pointed out, is that a massive hurricane still threatens millions of Americans in the Carolinas. Which as it happens it actually still does, and which probably explains why Trump continued tweeting about it—the Sharpie thing, and the storm’s disputed imaginary threat to Alabama, but not the hurricane itself—into Wednesday evening. As of Thursday morning, he was somehow still fucking complaining about it.

He has also tweeted about it twice more since I started writing this earlier this hour. In his Thursday tweets on the topic, which feature information provided to state and local governments four days before his original Alabama prognostications and which was issued before Trump himself was briefed on the storm, the President announced that he will accept apologies for the Fake News getting this all so wrong.

Whether it matters to you or not that these projections had all “long been ruled out” by the time Trump was briefed on August 29 depends on a number of factors and your capacity for being outraged by the stupid things that one soggy old dullard does on the daily. That there is a law against lying about the weather under color of the National Weather Service—the penalty is a fine or 90 days in jail—clearly doesn’t matter at all, at least insofar as there are so many more significant crimes than Criminal Executive Storm Inflation on Trump’s docket and also because no one currently appears to be doing much about those. It is clear, though, that this all matters to Trump a great deal. More, certainly, than the progress of the storm itself, or any of the many other issues that might have attracted the attention of more distractible chief executive.

The extent to which this perseverating dovetails with any of Trump’s broader strategic goals—which it does, at least in the sense that he has lately leaned heavily on the idea that the Fake News is trying to convince you that he was wrong about the weather, when in point of fact he has never been wrong about the weather and has a lot of experience with it—is, as usual, purely incidental. The extent to which the fixation reflects a longstanding approach on Trump’s part, which it does in the sense that he has never admitted any error, is notable mostly because everything that Trump does “reflects a longstanding approach.”

Nothing about the man has changed since 1991 or so, but various aspects of his personality have grown, or metastasized. He has always had a taste for big things, and an irresistible urge to associate himself with them. In another universe, Trump would be online claiming to be “very close friends” with Dorian, or offering to broker a deal with the hurricane to prevent it from Doing Hurt to the southeast. In this one, he is just doing what he does—taking some foolish falsehood that he prefers to the truth and insisting upon it, over and over, until it is just him talking to himself, agreeing with himself, congratulating himself, and then waiting for someone to come along and make it true for him.