Since 2017, eight women have gone to civil court and said they were sexually assaulted by the Wall Street financier Howard Rubin. One woman has since dropped her claim, but seven remain—six are suing as plaintiffs in one lawsuit in federal court, while another woman is suing on her own in state court, all in New York. While there are differences between what each woman says, certain details get repeated over and over. Each said they were recruited by someone who said they would be paid several thousand dollars to go on a date or do a photoshoot with Rubin. At some point they signed a non-disclosure agreement but were not given copies of it for themselves. Each woman says she was bound, beaten, and sexually assaulted by Rubin.

In the federal court lawsuit, attorneys for the women argue that Rubin’s actions violated federal anti-trafficking laws. Rubin’s legal team deny that their client committed rape. They say all the sex was consensual and the women knew BDSM and rough sex would be involved.

At the time the cases were filed, they often were put in the context of another man accused of sexual misconduct during the MeToo movement following the Harvey Weinstein scandal. Rubin, before the lawsuits, was previously infamous for his role in Merrill Lynch losing $275 million dollars in one quarter in 1987, a loss made infamous in the book Liar’s Poker. But since then, another case has become the national fixation—that of Palm Beach multimillionaire Jeffrey Epstein, who died in prison last month—leaving the cases against Rubin to fade into the background.

I stumbled upon this case by chance while looking into Rubin’s connection to Milwaukee Bucks co-owner Wes Edens, who at one point was subpoenaed in the federal lawsuit against Rubin. Jake Suski, a spokesman for Edens, told Deadspin that the plaintiffs chose not to depose Edens and “[Edens] has no relevant information to provide. Period.”

Now, with Epstein dominating the news, I had a basic question: Whatever happened to these cases? Prosecutors and police in New York City wouldn’t tell me anything, but the civil lawsuits keep pushing forward and, in doing so, expose details about the many tools—the non-disclosure agreements, the financial settlements, the fear and intimidation—powerful people can wield to keep everyone around them silent.

Each of the women have their own accounts of what happened with Rubin. According to the court documents, the women say they were recruited via Instagram or the portfolio website Model Mayhem, or through another person who knew Rubin. Most of them agreed to see Rubin more than once, and several say in their complaints that they were raped more than once. They also say they feared his wealth and influence.

The most straightforward account of how a night with Rubin is alleged to have unfolded comes from the only case filed in state court, by a woman using the pseudonym Julie Parker.

In her amended complaint, Parker said that she met a woman named Nicole Minton while visiting New York City on Nov. 3, 2015. They exchanged text messages, and Parker sent Minton a photo of herself. Minton told Parker that she would be paid $2,000 “to go out to dinner and drinks, with a wealthy man, but that she would not be required to have sex,” according to the complaint. The next day, Parker and a friend went to Washington D.C.

While in D.C., Parker got another text from Minton on the night of Nov. 4, telling her that she would meet a guy named “Howie” for lunch the next day at around 2 p.m. at Manhattan’s Russian Tea Room, per the complaint. That following day, Parker and her friend went back to New York City. After arriving, Parker dropped her luggage at an apartment where she was staying and got ready for her date. She had been told, per the court record, that Howie was a “really nice guy.”

Parker arrived, and a host escorted her to a table. Rubin came later, ordering expensive caviar and two glasses of Don Julio 1942 Anejo tequila, neat, for them, Parker recalled in the complaint. They two talked and, according to her complaint, Rubin kept encouraging her to drink more and get comfortable. Over the course of an hour they ate, drank, and talked about their lives. She told Rubin that she wanted to go to college. Rubin offered to fly her to Miami to watch a baseball or basketball game—if he liked her, the complaint stated. While she was 20 years old at the time, Parker said the restaurant served her alcohol and nobody asked her for any identification.

Later on, a woman called Stephanie came to their table and presented Parker with a non-disclosure agreement. Parker asked Rubin why she needed to sign it, and Rubin told her “it was required because he was married, had kids, and a business,” according to the complaint. In her lawsuit, Parker said that Rubin came across as a “caring adult, with promises of the good life, and that this was simply how things were done with the wealthy.”

And by this point, according to her complaint, Parker was intoxicated. She signed the NDA, but said she never got a copy of it for herself.

Rubin’s legal team filed a document in court this week that they say is the release form that Parker signed. Rubin’s lawyers have asked for the document to be admitted as fact, but Parker’s lawyers have not yet responded to the filing, or accepted or denied the document’s authenticity. But documents fitting the NDA’s description have been entered as exhibits in the federal lawsuit against Rubin. One dated Oct. 12, 2015, signed by a woman suing him using the pseudonym Macey Speight, is two pages long, and titled “confidentiality agreement and release.”

It reads: “In return for the payment of an agreed upon fee, I have voluntarily agreed to engage in sexual activity with (Rubin) including Sadomasochistic (SM) activity that can be hazardous and on occasion cause injury to my person ... This agreement covers each of the dates in question and a new agreement is not required for each subsequent date.” It later states “I freely assume all associated risks.”

The confidentiality clause reads: “I agree and promise that: The existence of this Agreement; the terms and provisions of this Agreement, including, but not limited to, the amount of money exchanged; the underlying facts to this Agreement; the identities of the parties or any of Rubin’s friends, relatives, or associates or colleagues; any information that can lead to discovery of the identities of the parties or any of Rubin’s friends, relatives, associates or colleagues; and all events and communications related to this Agreement (collectively ‘Confidential Information’), will not be disclosed by me to anyone, at any time in the future.”

The penalty for disclosing “confidential information covered by this agreement” is returning to Rubin “all monies previously received in connection with this agreement” as well as paying Rubin $500,000.

According to the complaint, the unknown woman named Stephanie left the Russian Tea Room once Parker signed the NDA.

Rubin already has been forced to address the NDA in the federal lawsuit against him. Portions of his deposition have become public by being attached to public filings in the case. During his deposition, from October of last year, Rubin was asked why he used NDAs. Part of his answer is redacted, but in the part that’s visible Rubin responds “and I also had seen online an NDA form that Justin Bieber had used for women that visited him, and that gave me the idea that I needed or wanted an NDA release form to use for myself.”

(A document obtained by TMZ in May of 2013 was reportedly given to people to sign before entering Bieber’s mansion. The penalty for talking about what happened in the mansion was $5 million. A later Bieber NDA, also obtained by TMZ, reduced that figure to $3 million.)

Rubin and his legal team don’t always call the above document an NDA. In the public snippets of his deposition, Rubin calls them a “consent and release form.” Rubin said he kept copies of them inside his apartment in a safe.

Can you sign away your ability to sue someone forever or report a crime? Brooklyn Law School professor Minna Kotkin broke it down into what she called categories of secrecy. One is a non-disclosure agreement, which, name aside, functions like any other contract a person signs.

“What they are designed to do is protect things that are supposed to be secret, like trade secrets, or to keep people from saying bad things about the company they worked for, or to not reveal the marketing techniques and things like that. That’s what they were designed to do,” Kotkin said. “They weren’t designed to hide legal violations. You find that someone is doing something fraudulent or embezzling or cheating on government contracts, or whatever. NDAs were not designed to address those situations. You’re supposed to be able to report legal violations regardless of any NDA.”

She added: “They are enforceable, to an extent, but not with regard to crimes.”

Another option is a confidential settlement, where a person agrees not to sue another person in return for an amount of money. Settlements don’t function like NDAs because they are agreed to after the events in questions, while NDAs look forward to something that hasn’t occurred yet. But they do have the same effect of keeping things secret.

Then there’s the general release. In a general release, you give up your ability to file a lawsuit because you are releasing all of your civil claims, Kotkin said. But even those do not guarantee that a lawsuit can’t be brought, she said, because a court will scrutinize the release to make sure certain requirements of a good contract are met, like: did the person know what they were signing, did you have legal advice, was there consideration, and did the person receive anything in return for signing the release?

Without an exchange, Kotkin said, “It’s just a promise and doesn’t have any legal effect.”

No matter what, a person cannot sign away their right to report a crime against them, and a subpoena from a government body overrides an NDA. And NDAs aren’t magical. As Kotkin put it: “Outside of an employment situation, which is a little bit different, they’re just regular contracts.”

There aren’t many key cases establishing legal doctrines about NDAs. Kotkin said one reason is people are careful, and another is the threat of suing people for violating one often is enough. Fights about NDAs rarely go to court. But, in a way, that’s the point; it’s not a truckload of legal principles that make NDAs powerful. It’s the fear they inspire. And it works.

Parker’s lunch date with Rubin continued, according to her amended complaint, with Rubin telling her more about his wealth and adding that he had an apartment in the building next door, the Metropolitan Tower. According to Parker, Rubin went on about how he dated famous models, including Playboy playmates, and had his picture taken with them. He kept a book with their photos and signatures. He even had photos of some of the playmates hanging on his walls. Rubin then asked Parker if she wanted to see his home on the 76th floor, per the complaint. She said she would.

Inside, Rubin fixed Parker another cocktail while she admired the penthouse. As he had said, inside there was a book of famous models and Playboy playmates, and photos of some of the most famous models and playmates decorated the walls. Parker drank her cocktail, and soon afterward began to feel lightheaded, according to the complaint. About 10 to 15 minutes later, Rubin told Parker that he wanted to show her his toy room—a small room, about 200 to 300 square feet, with ropes and toys for tying people up, as well as an electrocution device and “other devices and things that Ms. Parker had never seen before in her life,” per the complaint. Then Rubin asked if he could tie up her wrists, according to the court document, “for fun.”

Parker allowed him to tie her up, and Rubin told her that he would go easy on her. He also, per her complaint, gave Parker a safe word, “pineapples.”

(In a public portion of his deposition from the federal lawsuit, Rubin said he had two safe words. One was yellow light, which meant “it’s okay but slow down,” and the other was red light, which meant “stop immediately.” He also said that the room required a code to get in and just two people had it: him, and his assistant, Jennifer Powers.)

According to Parker’s complaint, Rubin lightly tied up her wrists and gently slapped her across the face. Rubin asked if this was okay, and Parker said yes. Rubin then tightened the ropes, making them very secure, forcing Parker to “totally relinquish control,” the complaint stated.

What followed was, according to her lawsuit, “the most hellish encounter of her young life.” Rubin smacked her face, hard. She yelled “pineapples” and asked Rubin to stop. He continued. He ripped off her blouse, exposed her breasts, and attached a device that clamped down on her nipples, then pulled on them. When she begged him to stop, Rubin punched and smacked her with his fists. Rubin called her “a piece of shit, and a whore, and he kept saying that Plaintiff was just as bad as the other whores,” the complaint stated. Parker tried telling him to stop, but Rubin told her that begging would only make it worse.

When it was over, Rubin told Parker that she was a “whore” and needed to clean herself up, per the complaint, then thanked her for a “pleasurable experience” and said he’d like to see her again. When Rubin left, he told Parker that he had to meet his wife and children for dinner.

Parker grabbed her clothes and left Rubin’s place as fast as she could, going back to the apartment where she had been staying, according to her lawsuit. She called a friend, screaming and crying, and asked the friend to grab her belongings and meet her downstairs, in the apartment lobby. Parker then told her friend what had happened, per her complaint, and she recorded a short video to document her injuries.

(Parker’s face and her voice have been altered to protect her identity.)

Parker’s friend submitted an affidavit to the court, saying that Parker called her immediately after she left Rubin’s apartment. She said in the affidavit that Parker was “in a frantic and distraught state, crying, screaming, and upset, and in a great deal of physical pain, and emotional distress.” When Parker got back to the apartment, the friend said in her affidavit that “she was extremely upset, and it was clear that she had been crying, and had just been through a very traumatic incident.” Parker then “explained to me in graphic detail what Rubin had just done to her.”

In her original complaint, Parker said she was paid by a man who knew Rubin and whom she also was suing. That man was later dropped from her lawsuit. Parker said she never contacted Rubin again.

Parker eventually enrolled in college and started taking classes, but “her life and emotional stability began to fall apart,” according to the complaint. She started drinking to excess and doing drugs. In 2016, she started having anxiety and panic attacks. Parker’s court documents include medical records from Cedars-Sinai saying she suffered palpitations, substance abuse, and anxiety.

“Our client was a young and vibrant 20 year old with a promising future. The horrific and violent encounter she experienced with the defendant, as detailed in the lawsuit, is something no one should have to endure,” Parker’s lawyer, Kevin Landau, said in a statement. “We hope that her courage in coming forward will help other victims to be strong in the face of adversity.”

Julie Fennell is an associate professor of sociology at Gallaudet University, where she studies the pansexual BDSM subculture. Fennell explained that it’s important to understand that there is kink inside the pansexual BDSM subculture, aka “the scene,” and then there’s kink outside of the scene—the difference being that part of being in the scene is agreeing to follow very specific rules. With kink that happens outside of the scene, there’s no guarantee that people are following the same rules.

Fennell compared it to the various levels of baseball; there’s Major League Baseball, with its many rules that people at that level agree to follow, and there’s the baseball you play with friends after work or on the weekend, where the adherence to MLB’s standards probably isn’t the same.

Without knowing if Rubin was in the scene, there’s no way of knowing what rules he believed he should be following. But, at least within the scene, Fennell said, safe words are seen as a final recourse. There are other ways to communicate that you want someone to stop, and those methods should work.

“Usually, they are used as last resorts and the idea of that last resort is that, by gosh, you’re supposed to follow it. If this person uses their safe word then you are supposed to stop doing whatever it was that you were previously doing. That’s the whole point of having a safe word,” Fennell said.

Fennell said it was “pretty rare” for people in the scene to be accused of violating safe words.

“I think that everyone who understands what BDSM is, i.e. consensual kink, and to most people the phrase consensual kink is redundant. Right?” Fennell said, “In order for it to be kink, it must be consensual. Otherwise, it’s just abuse. You have to have a negotiation with somebody that makes it reasonably clear that you both want this thing.”

In a portion of his deposition, Rubin discussed his BDSM rules. He said he talked to the women beforehand about what to expect. He said he used safe words. And Rubin talked about how he felt BDSM participants should communicate that they wanted someone to stop: “Certainly verbal communication would be the number one—the number one methodology of stopping BDSM play. I think there could be facial expressions. There could be body language. But by far, the number one methodology was verbal.”

A lawyer asked Rubin if he would stop when told to stop. Rubin answered, “I would always stop.”

Most of the women suing in federal court didn’t mention safe words in their complaint, but questions about them come up in later court documents. One woman, using the pseudonym Lauren Fuller, said she recalled being a given a safe word by Rubin, but she didn’t remember the exact phrase. During Fuller’s deposition, a piece of which was attached to a court filing, she said Rubin did stop abusing her but only after she said the safe word several times. Another woman, using the pseudonym Rosemarie Peterson, said in her deposition that she did recall Rubin having a safe word but “he never stopped, even if you used it.”

During Peterson’s deposition, a lawyer asked her: “Mr. Rubin had told you repeatedly that if he had encounters with you, that you could expect to be bruised; isn’t that right?” Peterson answered, “Yes. And I also could expect that if I said stop, that there would be stopping. But he would always continue, even if you wanted to slow down or whatever.”

Rubin’s response to Parker’s lawsuit admits to meeting with Parker, and giving her an NDA, but the answer filed with the court says he “did nothing that would cause Plaintiff to scream or cry.” It goes on to say that the video “evidences no such condition of Plaintiff.”

In the federal lawsuit, Rubin’s lawyers have argued that all the women “consensually engaged in BDSM, or rough sex, with Mr. Rubin for money, and that not one was forced, tricked, or deceived into doing so.” They lean heavily on friendly and flirty text messages the women sent Rubin, and that several of them visited Rubin more than once. In one document, filed with the court, attorneys for Rubin call the women’s legal filings “shameful” and “malicious attempts to extort Mr. Rubin into settlement to avoid humiliation.”

Here is how Rubin’s lawyers summarized their arguments in a memorandum of law seeking summary judgement:

The record shows: (1) Plaintiffs understood they were meeting Rubin to engage in rough sex for money; (2) Rubin was “upfront” with the women, forthrightly explaining in detail the nature of the encounters, and providing “safe words” to terminate any encounter; (3) following their meetings with Rubin, each Plaintiff, with one exception, repeatedly expressed that she had enjoyed her time with him, and wished to engage in BDSM sex with him again; (4) no Plaintiff indicated in any way—either to Defendants or anyone else—that she had been raped, assaulted, battered, falsely imprisoned, traumatized or seriously injured; (5) several Plaintiffs aggressively and explicitly solicited Rubin to engage again in rough sex; (6) three Plaintiffs encouraged close friends to have rough sex with Rubin; and (7)all but one Plaintiff returned for multiple visits with Rubin, over a period of months or, as to some, years.

The motion also points to the documents the women signed, saying “the second paragraph of the document states unambiguously that the parties would engage in potentially injurious rough sex for which the women would be paid.”

Rubin’s lawyer, Ed McDonald, issued the following statement to Deadspin: “Mr. Rubin emphatically denies the allegations. All plaintiffs were adults who fully consented to engage in all the activities about which they now complain. Mr. Rubin looks forward to clearing his name in his day in court.”

Rubin’s personal assistant, Jennifer Powers, is a defendant in the federal lawsuit. They first met when he visited a nightclub where she worked back in 2007, then dated “on and off” for about three years, then broke up in 2010, followed by her going to work for Rubin in 2011 as his executive assistant. Powers also has given a deposition, and in the portions that have become public she talked about her job and how it worked. Her duties included responsibilities like doing Rubin’s gift shopping and making reservations for him at restaurants; she called them “day-to-day tasks.” She did not introduce Rubin to women—Powers said other people did that—but because of her job she did help get the women to New York and then back home.

“Well, I was his assistant,” Powers said while answering one question. “So oftentimes he would text me and say hey, so and so is going to come to New York, here’s her number, would you mind booking her a flight.”

Afterward, Rubin would send Powers a message on WhatsApp telling her how much to send to the woman via PayPal, and Powers would do just that. She recalled Rubin telling her to pay the women anywhere from $1,000 to $5,000. Powers also said she was the person who presented women in the federal lawsuit with their NDAs, which they signed with her. When asked if Rubin was ever with the women when they signed the NDAs, Powers said “no.”

Powers also was involved in maintaining the apartment. She bought toiletries and “basically made the apartment as homy as I could. Everything that anyone could want while they were staying with us in New York.” She arranged for a cleaning service for the apartment. She bought BDSM sex toys and furniture for it. Asked who stayed there, Powers said during her deposition that she recalled it just being Rubin and the women who were flown to New York to meet him.

Documents in the federal lawsuit contain reams of friendly seeming messages between the women and Powers—dated both before and after the dates when the women say they were raped. Rubin’s defense team argues the messages prove that everything that happened was consensual.

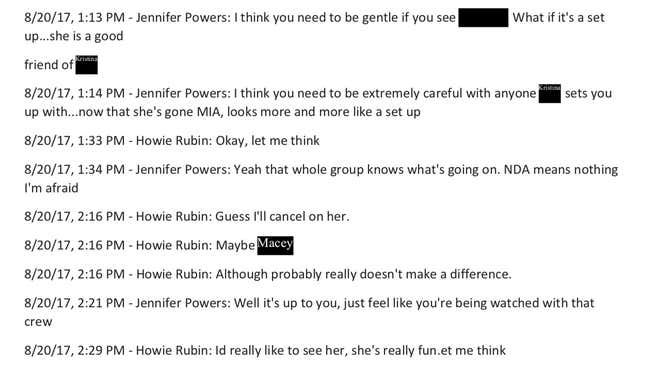

But then there’s this exchange. (All the names of the plaintiffs have been redacted and replaced with their pseudonym.)

Powers asked to be dismissed from the Trafficking Victims Protection Act portion of the lawsuit, arguing that she didn’t know about any of the alleged coercion.

Lawyers for the women fought that request, saying Powers knew about it and profited from it. In their filing asking to keep Powers on, lawyers for the women highlight two text messages, which their court documents quote. One is a message Powers sent saying, “You beat a hot girl and got laid! What’s there to be upset about!!” (The court filing doesn’t make clear who received the message.) Another message is described as Powers responding to a picture sent by Kristina Hallman (another woman suing Rubin) of another woman’s breast injuries after Rubin beat her. In the message, as described in court records, Powers wrote: “[emoji][emoji][emoji] I know. Speaking to her now Thank you for being a good friend . . . She’ll be OK, don’t worry. [emoji] . . . Are you with [Caldwell] now? . . . I need her address, want to send her some stuff I’ve found to be helpful.”

Earlier this month, U.S. District Judge Brian M. Cogan denied Powers’s request regarding the Trafficking Victims Protection Act portion of the lawsuit. Cogan wrote: “This text message has high probative value because a reasonable juror could infer from the message that women were injured during their encounters with Rubin, which makes it more likely that Powers knew about or recklessly disregarded plaintiff’s lack of consent than if she did not send this text message.”

Powers’s salary working for Rubin was $15,000 a month. Powers said she stopped working for Rubin around 2017. When asked why, she responded, “This lawsuit was a big part of it.”

Lawyers for Powers issued the following statement to Deadspin: “Ms. Powers denies the remaining allegations against her and looks forward to clearing her name.”

Rubin has tried, but hasn’t been able to get the lawsuits tossed. Manhattan Supreme Court Judge Doris Ling-Cohan denied Rubin’s motion to dismiss in February. In her ruling, Ling-Cohan wrote that Rubin’s arguments were “without merit” and both of Parker’s actions would proceed. That lawsuit, according to its docket, is going through the discovery process, where each side gathers evidence.

Lawyers for Rubin and Powers each filed motions for summary judgement in the federal lawsuit, and the rulings on those motions were sealed. But the case as a whole was not tossed. Future courts dates are still being scheduled, and a pretrial conference is set for October.

Because the women are describing crimes that happened to them in Manhattan, I reached out to law enforcement in New York: Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Geoffrey Berman, and the New York Police Department. I asked if their offices were aware of the cases and, if so, if they were looking into possible criminal charges. Everyone declined to comment. Dawn Dearden, spokeswoman for Berman’s office, said in an email: “Sorry, I can’t confirm whether or not we are investigating a specific case or individual.” Naomi Puzzello, spokeswoman for Vance’s office, said: “We will decline comment, as we do not confirm or comment on investigations.”

The NYPD responded with a statement that didn’t address my questions at all: “The NYPD takes sex crimes and sexual assault very seriously and encourages anyone with information about such a crime to report it to police so perpetrators can be prosecuted and justice can be secured for survivors.”

Justice for survivors has been a popular phrase since MeToo began. But that’s rarely what the ensuing events have actually looked like. For a while, the conversation was about power. Look at the power Harvey Weinstein had, look at the power that Kevin Spacey had, look at the power that Louis CK had, look at the power Larry Nassar had, and look at how little power the women and men speaking out against them were able to wield. From there, the public narrative shifted to what would happen to these powerful men. Would they be redeemed, if they should be at all, and what might that look like? What would happen to the people who came forward, and what that justice done under their names would look like, didn’t garner as much speculation, maybe because it’s human nature to avoid an uncomfortable conversation without easy answers. Or maybe it was just the same old biases.

But those battles, like these lawsuits, have gone on, peeling away at the layers that exist but rarely make front-page news: the assistants who protect their bosses from the messy details, the NDAs that scare people in silence, and the fear that’s been baked into the subconscious for so long it’s hard to know when it began, and if there will ever be an end.

There’s no way to predict how the Rubin case will end. But what’s already known lays bare how power works, if you feel like listening.

Correction: Sept. 19, 9:42 p.m. ET: An earlier version of this article referred to motions for summary judgement as motions to dismiss. It has been corrected.