A New York judge gave a group of insurance companies the go-ahead to seek evidence that the NFL sought to share cover-up strategies with tobacco companies as part of a ferocious, years-long legal battle over which side will pay for claims related to the league’s concussion settlement.

In a 14-page decision, Justice Andrea Masley of the New York State Supreme Court permitted the insurers to add the word “Lorillard” to its list of approved electronic search terms as part of the suit’s discovery process. Lorillard was a tobacco company that had been partly owned by Preston R. Tisch, the late co-owner of the New York Giants. It was purchased by R.J. Reynolds tobacco in 2014. A court-appointed special referee had rejected the insurers’ request in February, but Justice Masley overrode that decision. She even swatted down the NFL’s objection to the inclusion of the search term with a dash of élan (emphasis mine):

The NFL’s objection that searching the term “Lorillard” would result in many irrelevant hits, such as news reports because it is a multinational company, is without factual basis. The databases to be searched belong to the custodians, not Lexis, Westlaw or Google. This request is not speculative. Rather a document that connects big tobacco’s response to the medical conditions caused by smoking and brain disease caused by concussions would be far from tangential, as the NFL asserts. Given the factual predicate here and the significance of positive results, adding Lorillard as a search term is anything but a fishing expedition.

It remains to be seen whether the insurers will discover any sort of smoking gun by poking around on the term “Lorillard.” A March 2016 New York Times story referenced in Justice Masley’s decision insinuates some rather tenuous ties between the NFL and the tobacco industry:

- A 1992 request from Tisch that Lorillard’s general counsel, Arthur Stevens, contact then-NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue about what the Times described as “certain legal matters.”

- Personal correspondence between the league and the tobacco industry that indicated friendships, dinner invitations, and “a request for lobbying advice,” in addition to records indicating that “that the two businesses shared lobbyists, lawyers and consultants.”

- The NFL’s decision, in 1997, to assign a lawyer named Dorothy Mitchell to provide legal oversight to its since-disbanded concussion committee, which would later come under fire for faulty research that downplayed the significance of head injuries.

Mitchell had previously defended a tobacco industry trade group in a second-hand smoke lawsuit, in addition to a smoker’s suit, though she denied to the Times that she was responsible for the legal strategy in those cases. Tisch had also served on that tobacco trade group’s board. An NFL spokesman told the Times that Mitchell did “not have any responsibility or any role in directing the research” of the concussion committee, but Dr. Joseph Waeckerle, a former member of that committee, told the Times that Mitchell would ask committee members questions like this: “How can this affect us? How can this be studied? How should we view it? Is this a legitimate concern, or is this part of somebody’s zeal, and do we need to be concerned?” The league responded to the Times’s story with a lengthy statement that prompted a volley back from the Times.

The biggest takeaway from that initial Times story is that the NFL had fudged its concussion data. What had been known until then was that the league had been using specious logic to make spurious claims. The Times’s discovery was enormous, but it came years after the league had gotten deep into settlement talks with the thousands of former players who had sued it for concealing its knowledge of potential links between football-related head injuries and the onset of degenerative brain disorders. The insurers are still trying to suss out what the NFL knew and when it knew it, and whether or how this might have influenced the league’s decision to manipulate its data, which the insurers argue would cancel their obligation to cover the hundreds of millions of dollars in settlement claims and legal fees.

Per The Athletic’s Daniel Kaplan, who was first to report on Justice Masley’s ruling, the NFL initially sued the insurers back in 2012 to ensure coverage as the players’ class-action gained momentum. The insurers’ suit against the league, which in part alleges that the league settled with the players without conducting any discovery or taking a single deposition, has grown to include more than 30 co-plaintiffs, though some have since settled, including one as recently as last month. The parties have been warring over what to include in discovery, and the NFL has blown off multiple deadlines for submitting discovery materials, which is what led to the appointment of the special referee as mediator. Numerous case filings and exhibits have been redacted or filed under seal.

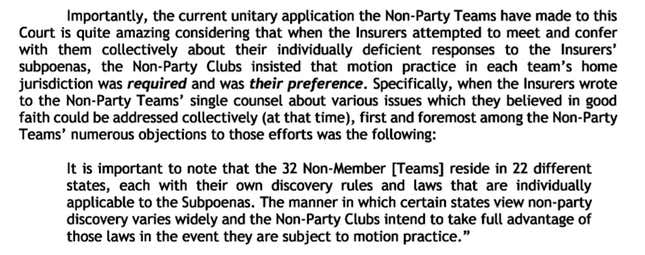

There have also been other indicators of just how nasty this has become. Back in June, per Kaplan, nearly 30 attorneys were present for a contentious hearing before Justice Masley. A lawyer for the insurance side brought a copy of the 2013 book League of Denial into the courtroom and left it on a table facing the judge for the duration of the 75-minute hearing. Frustrated by the league’s stall tactics, the insurance companies in December 2017 subpoenaed all 32 teams, even though the teams are not party to the case. In April, after more inaction from the league, the insurers filed actions in those states to enforce the subpoenas, which resulted in the league seeking a temporary stay, which in turn was granted. But this allegation, outlined in an April 29 letter to Justice Masley from one of the insurers’ lawyers in response to the league’s stay request, is a perfect indication of the sort of circular tactics the NFL has used to delay discovery:

So: The insurers subpoenaed the teams because that’s what the league said it wanted, only to have the league turn around and claim it was too burdensome for teams in 22 different states to answer subpoenas.

The league has claimed, in turn, that it has been also burdened by the extent of the insurers’ discovery requests. At that June hearing, per Kaplan, a league attorney told Justice Masley three million documents had been searched and that 14,000 documents had been handed over. And in Justice Masley’s recent ruling, she noted that the NFL had already forked over 710,000 documents.

Justice Masley’s ruling sided with the NFL by requiring the insurance companies to hand over reinsurance and financial reserve information, since the league wants to be sure the insurers aren’t covering for their inability to assume their risk obligation with the NFL. Likewise, she upheld the special referee’s denial of the insurers’ requests to allow the names “Bennet” and “Will Smith” to be used as electronic search terms. “Bennet” refers to Dr. Bennet Omalu, the neuropathologist who first identified CTE. “Will Smith” portrayed Omalu in the 2015 film Concussion.

Justice Masley’s decision can be read below: