Much like its cousin, the baseball cap, the baseball bat seems pretty simple, at first glance. Take a reasonably cylindrical piece of wood, taper it as necessary, put a little nub on the end so your hands don't slip off, and swing. Hit the ball too low, and you'll pop it up.

Hit it high, and it'll head for the ground.

Swing too early or too late, and it'll go to the left or the right, respectively (may not apply to lefties).

Unlike the baseball cap, the bat seems to have room for some useful improvements. For example, changing the shape of the handle can help prevent hamate bone fractures in the hand and might prevent players from launching the bat into the stands after losing grip during a swing. Intrepid scientist and right fielder Sammy Sosa conducted his own experiments on advancements in bat composition, despite Major League Baseball's frowning upon them:

Other inventors have set their sights on changing the shape of their barrel to accomplish one of a variety of goals. The following are only a few of the many, many attempts at freeing baseball players, major- and minor-leaguers alike, from the tyranny of cylindrically-barreled bats.

Streamlined Baseball Bat Or The Like - U.S. Patent No. 2,169,774

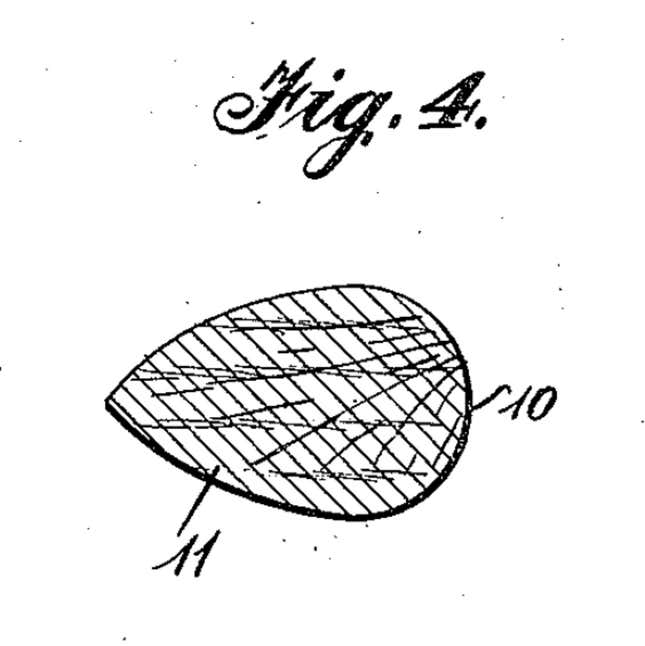

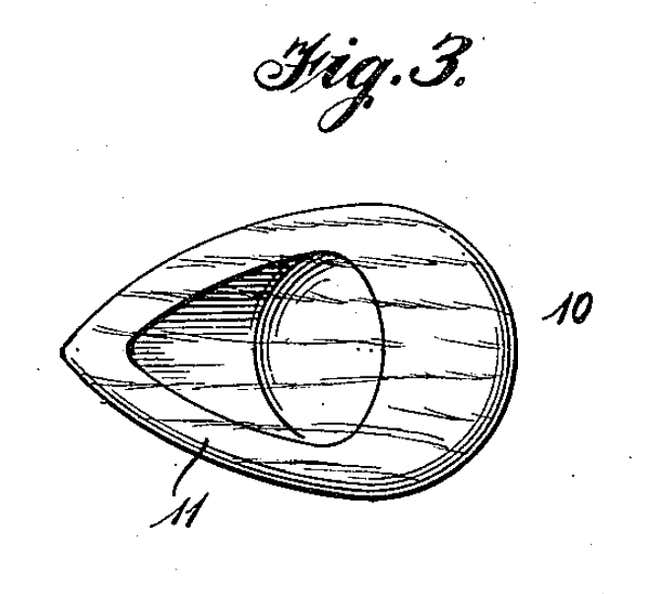

Above is a cross-section from a streamlined bat. The right side is the one that strikes the ball, and reasonably approximates a normal bat surface. The left side, you'll notice, is tapered. To what end, you might ask?

It has been proposed to form golf clubs to simulate a streamlined shape, that is a shape wherein the trailing side of the head of the club is so formed as to avoid the air eddies when the club is swung, which eddies cause the resistance of the air while flowing into the partial vacuum produced by the motion of the club. The principles and effect of streamlining are well understood, having been thoroughly investigated by the air craft industry and in many other arts since the development of that industry. (emphasis added)

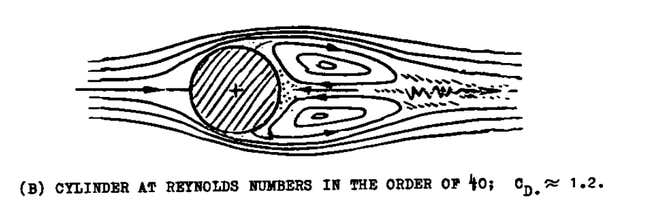

To illustrate this problem, here's a diagram of the airflow over a cylinder:

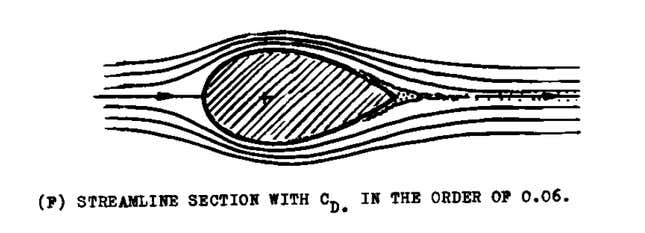

Air is flowing from left to right, so imagine this is showing a bat moving from right to left. Behind the bat, on the right, air is recirculating, and causing drag. Here's the same cylinder, or bat, with a tapered portion on the trailing edge:

[both from Fluid-Dynamic Drag (Hoerner, 1965)]

There's still drag, but it's significantly decreased. With less drag, the bat speed should increase. Six decades after this patent was granted, another inventor would create a bat dimpled like a golf ball in an effort to increase bat speed, and claimed the reduced drag increased bat speed 3-5% (translating to up to 10-15 feet on home runs).

The above picture was of a cross section of the bat. Here's a view from the end:

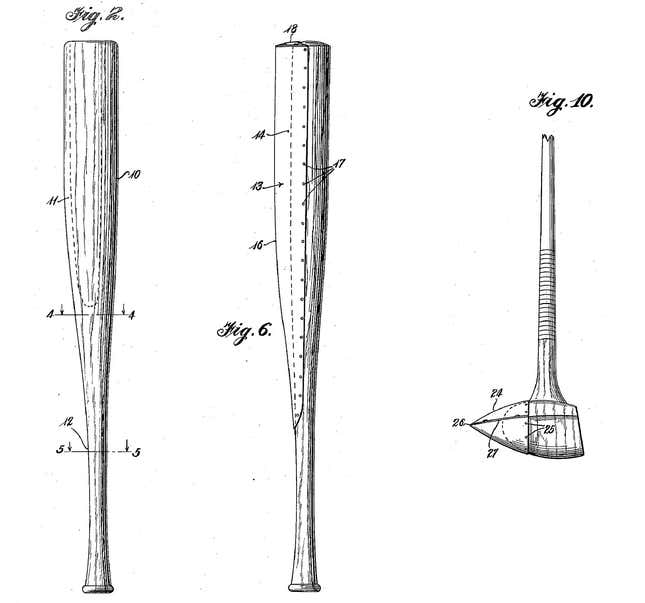

You might be wondering why it doesn't look the same. The answer is that to avoid increasing the bat's weight too much with the added tapered portion, part of the interior of the bat is hollow. Here's the whole bat, to get a better sense of it:

Notice, on the left bat, the U-shaped dotted line: that's the hollow portion. You can see the tapered portion of the barrel sticking out to the left, which is why the handle looks off-center. The barrel is wisely untapered down toward the handle end, so that a player can grip it normally while bunting.

The bat in the center offers an alternative solution. Instead of buying a prefabricated tapered bat, you could simply buy a thin, metal tapered portion and attach it to a bat you already own. The patent doesn't indicate if this would void the bat's warranty, but I can't imagine it would help. For good measure, on the right, you can see the same idea as applied to a golf club.

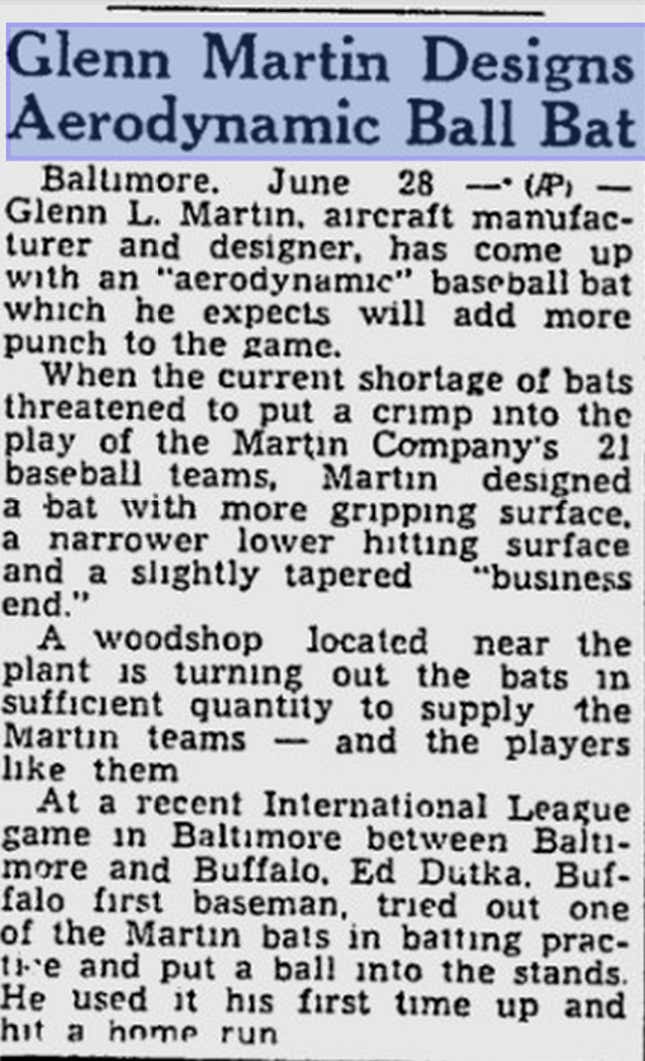

In his patent, the inventor notes that this principle of streamlining was "thoroughly investigated" by the aircraft industry. In fact, it was so thoroughly investigated that Glenn L. Martin, the founder of the Glenn L. Martin Company (which is now the "Martin" in Lockheed-Martin) worked on an aerodynamic bat during World War II:

They weren't just for the Martin Company's 21 (!) teams, either. The majors actually had a shortage of bats during World War II, and Martin, an avid Washington Senators fan, stepped in to help. As George Case, a prolific base-stealer for the Senators, explained it:

Glenn Martin was an avid Washington Senator fan and when he read in the papers that we were having bat problems he had his engineers design a bat for us that looked like an airplane wing. It was tapered at the hitting end, and actually the principle of it was very sound. The swing weight was excellent. I don't know why none of the bat manufacturers ever followed up on that. Martin made us ten or twelve dozen of those bats and we used them. They did break easily, which was one of the problems.

It's unclear from these descriptions if the "slightly tapered hitting end" is similar to the design shown above, but it's a reasonable guess.

The idea of a business mogul devoting much—perhaps too much—time and effort to his interest in baseball should sound familiar, but this endeavor didn't work out quite as well. I asked Stan Piet, Lockheed-Martin's archivist, if he had any more information, or photos of Martin's bat in action, and got this in response:

We're familiar with the bat story but we've never seen anything concrete that substantiates it in any of the Martin documents we hold. Conversations with former WWII Bombers team members confirm its development and usage but they've all passed on now. What I can relay is that they saw no value in the design and it was quickly dropped from usage.

This was probably for the best: given a few more years, Martin might have come up with a bat that was invisible to radar and cost the government $312,000 each.

So what if you wanted a baseball bat that was neither aerodynamic, nor a particularly good idea?

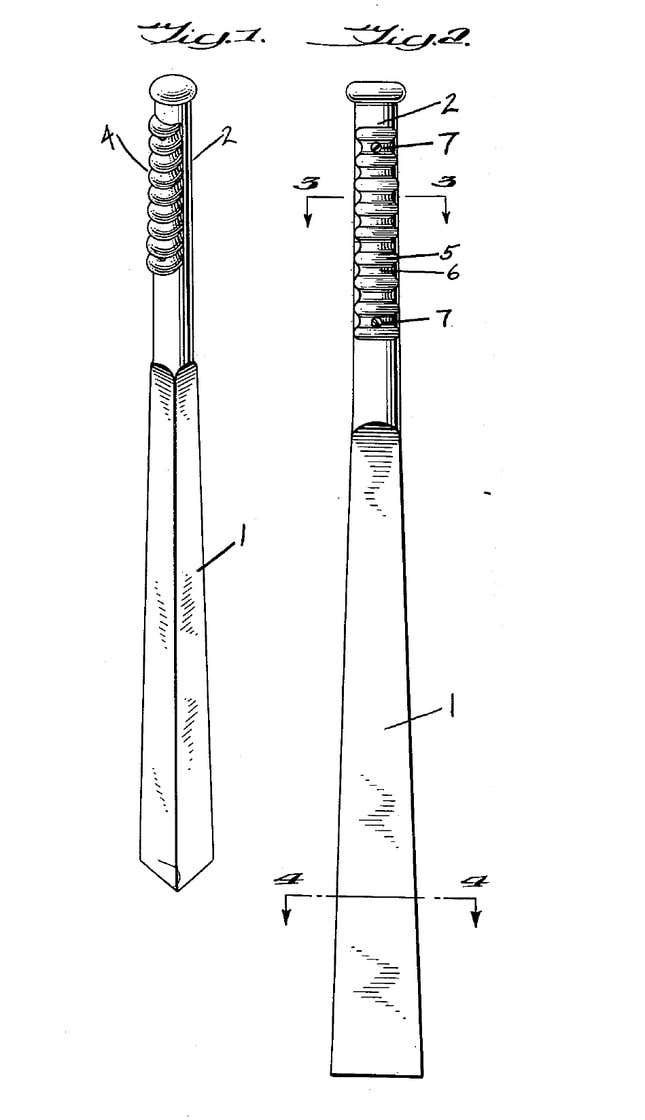

Baseball Bat Comprising a Square Cross-Sectional Hitting Area - U.S. Patent No. 3,104,876

Just in case you were confused as to what a square looks like, there is a helpful picture of a square cross-section

You should be wondering why this exists. If you're not wondering why this exists, please go look at the bat again. Here is the inventor attempting to explain why this exists:

The "prior-art" baseball bat having a circular cross-section along its entire length provides a curved striking face to the ball. Because of this curved striking face a large number of "foul-balls" are hit during each game. It is an object of my invention to provide a baseball bat having a flat face on the striking part of the bat whereby the batter is able to hit the ball with more control.

Thus in a baseball game where all batters use the fiat-faced bat the number of balls lost during a game is considerably reduced[.]

So, the problem is that too many foul balls are being lost...? I suppose this might stop foul balls that go straight back, but I don't see how this would prevent foul balls from going left or right. And unless you're playing Little League at a park with a piranha-filled lake directly behind home plate, it doesn't seem like lost foul balls are so much of a problem that you have to use a bat that looks like the Washington Monument.

In experiments using the baseball bat embodying my invention it has been found that an average batter will be able to improve his hitting accuracy remarkably.

Inventor: "Here, baseball player. Try this square bat."

Baseball player: [throws bat, hitting the exact center of a garbage dump]

Inventor: [shrugs, puts comically-exaggerated check mark on clipboard]

The large grip does serve an actual purpose, however:

In a preferred embodiment of my invention I have provided a finger-grip 4 on the bat handle 2 to assist the batter in holding the bat properly so that one flat surface of the striking portion will be presented to the ball during the batter's swing.

This is smart: otherwise a corner edge might hit the ball, which would either make the ball leave the bat inaccurately, or slice it in half, depending on whether or not it's the steroid era. Fortunately, this bat never caught on, and foul balls have remained the restaurant-destroying, child-endangering, lady-terrifying menaces we've grown to love.

*Thanks to Prof. Alan M. Nathan of the University of Illinois for the first two gifs, from his great Physics of Baseball site, and to Stan Piet for looking into the Martin baseball bat.

Bring Back Anthony Mason is a patent attorney in New York. Rest in peace, Mase. / Image by Sam Woolley.