Ninety-two years ago, a 34-year-old Chicago man named Joseph Wozniak woke up missing one of his balls, which had been surgically removed by hoodlums.

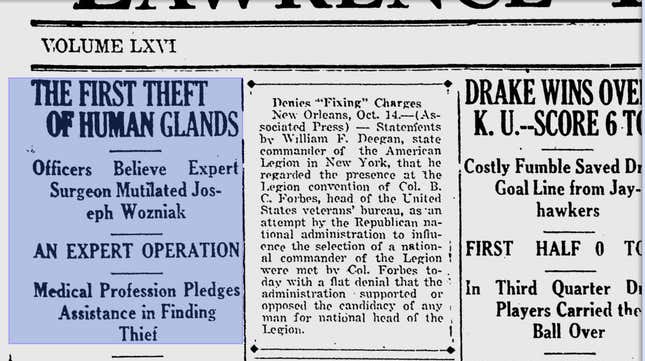

As the Lawrence Journal-World had the story, he was on his way home from the bar when "four men leaped on him, put a bag over his head, and loaded him into an automobile." They then drugged him and stole one of his testicles, presumably "for an experiment in gland transplantation, perhaps for the purpose of rejuvenating some infirm or aged man." This is how the front page of the paper looked on Oct. 14, 1922.

Papers all over the country picked up the story. Readers of the Sunday Morning Star in Wilmington, Del., heard a policeman's warning that Chicago "may be confronted with the same situation that faced the authorities in China 2,000 years ago." The Spartanburg Herald in Spartanburg, S.C., covered yet another victim, who came forward only after hearing of how Wozniak's ball had been robbed. The Fort-Worth Star Telegram reported on the main suspect in the case, "an aged millionaire who is alleged to have paid $100,000 for a pair of stolen glands, on the eve of his marriage to a woman, 25, he being 68 and badly wasted as to health and vitality." Two years later, the Ottawa Citizen informed readers of a new trend in which poor young men were selling their balls so that a Dr. Voronoff could graft them into the scrota of rich old men.

The First Theft Of Human Glands ... Chicago Police Fear Epidemic Of Gland Piracy Following Attacks ... 'Gland Larceny' New Banditry In Windy City ... Police Net Tightening On Aged Millionaire Accused In Chicago Gland Theft... Poor Men Selling Glands To The Wealthy And Aged For Restoration Of Youth ... These are great headlines, evoking both a century-old panic over the possibility of anonymous roughs drugging you up and cutting your balls off, and a time when people who read broadsheets wanted to read about what was happening in the world in plain, direct English. Run anything like that today and you'd have some asshole getting at you the second you hit the publish button.

"'Theft of human glands,'" the asshole would say. "SMDH. Clickbait."

Used as an epithet, the word "clickbait" presents a tautology as a criticism. You published something, and want people to read it, too.

Taken at face value, it's less than meaningless—it's self-negating. It's obscurantist, senselessly treating journalism as if the high modernist values of contingency and complexity were journalism's own. It's moralistic, proposing a false binary between stories that serve the public interest and those cynically presented just because people will read them. It's suspicious, hostile, and patronizing. It confuses decorum with integrity.

In theory, it's a term for something without inherent merit, published principally for the purpose of tricking people into reading it. In practice, it's something else.

Clickbait is stories about testicle thieves and Joe Gould's Secret. It's "The Loser."("Sure, Floyd Patterson is a loser. Esquire trolling for hateclicks, ridiculous.") It's "NSA collected US email records in bulk for more than two years under Obama" and "Mila Kunis: Side Boob Or Butt, But Never Both On-Camera (PHOTOS)." It's any way of presenting a story that doesn't follow the dreary precepts that prevailed in high-end U.S. newsrooms over the last half-century—a period, incidentally, of widespread newspaper consolidation that allowed those newsrooms to be just as self-serious as they liked in the absence of any real competition. It's anything anyone might actually want to read.

Closer to home, it's a story about ESPN commentator Bob Knight drawing a comparison between basketball players being paid for playing basketball and rape ("This isn't an article, it's a word search ... this is just clickbait"), or the relatively low level of play in our domestic soccer league ("This is how your Deadspin soccer fan-click sausage is made"), or how a bad study badly overstates the amount of sex trafficking associated with the Super Bowl ("This is the worst Unworthy click bait EVER!"). It's a term for everything, which means that it's a term for nothing.

The other day, our Tom Ley wrote a story about an international trade union federation's report on the abuse of migrant workers who are building $100 billion worth of soccer-related infrastructure in Qatar for the 2022 World Cup. The report, using a fairly conservative methodology and relying on figures reported by two embassies, concluded that at least 4,000 laborers will die of causes related to these construction projects.

NGO reports on abuse of Nepalese migrant workers generally aren't the stuff of viral content. Knowing that, we chose a provocative headline that compared the number of people Qatar's World Cup is expected to kill to the number of people killed on 9/11. We drew on the emotional resonance of the 9/11 attacks to make two points: a) a lot of people are expected to die making this World Cup, and b) those people are no less important than the people who died on 9/11, and their deaths are no less tragic. Doing so, we figured, would draw attention to the story and impress the gravity of the report's findings on readers. It worked; the story has about a quarter of a million pageviews, around seven times as many as a similar story drew a month ago under a more neutral headline. It also attracted a fair number of comments like this:

In the initial report the use of 9/11 imagery struck me as an odd choice, more so done as click-bait more than anything ...

It's so obvious that it's embarrassing to have to spell it out, but, yes, we used that imagery because we thought it would make people click on the story and read it. The idea was that people would say, "More deaths than 9/11?!" and then read an article they might otherwise not have, about workers having their passports stolen and being forced to drink saltwater and dying in huge numbers. Some of them, we hoped, might draw a connection between something they understood on a gut level and something happening in a far-off part of the world. We published something, and we wanted people to read it.

Raising the cry of "clickbait" is a healthy response to the world as it is. (You are the product, not the customer; Darren Rovell exists, etc.) Using the word is a way of saying, I know you want something from me, because the Internet is the cleverest mechanism ever contrived to get people to want, buy, and be interested in things, and I'm not having any of it. It's lazy and cynical and still better all around than accepting that because the imperatives of the market have given primacy to animated images of household pets, their value should be taken as a given.

Where it doesn't work, though, even when intended as something more—or at least other—than a simple "A=A" proposition, is in its imputation of motive. The wised-up Internet consumer, surveying a world of constant demands on his attention and omnipresent media and wanting to express his awareness of how the scam works—You're just baiting me to get those clicks—ends up essentially adopting the language and prissy airs of the pseudo-academic media critic. There are thousands of Jeff Jarvises now, willing to laud your book-length post on the history of black quarterbacks in the NFL as a clever bit of affiliate marketing and bet on search. There are tens of thousands of imagined Poynter Institutes, every one employing an army ready to scour the press to hold it to a certain standard of decency. There are hundreds of thousands of people who have learned a knowing, insidery tone, to view journalism through the prism of clicks and circulation, and to use and think in terms that sound like, even if they aren't, those of the trade. I know you get paid for those clicks.

This is, in the strictest sense, a paranoid mentality, and carries with it all the vagueness and generality usually associated with paranoia. The citizen media critic, trained to suspect dark and cynical motives, loses the ability even to articulate specific criticisms. An article isn't covering dumb, useless subject matter—it's clickbait. A headline isn't misleading—it's clickbait. A reporter isn't clearly compromised by her intensity of feeling about a subject—she's just churning out clickbait. A universe of concerns, each one as specific and unique as what it's addressing, is entirely subsumed into a single meaningless word that functions as nothing more than the expression of an attitude of superiority. I'm too smart for that to work on me.

If journalism were as easy as tricking people into pushing buttons, it would have been automated by now. It's a trade, and the art is in satisfying a bewildering variety of competing interests by working not only in service of all the impossibly interesting stories in the world—some of them very important, some not very important at all—but also the impossibly busy people who might read them. Some are interested in celebrity breasts, some are interested in NSA spying, and most are interested in both and other things, too. You go out and find stories that might appeal to them, you point them to other people who have found such stories on their own, and you try to get their attention, just as Darren Rovell and brand marketers and the Poynter Institute and the New Yorker are. If you find one about people getting mugged for their testicles, you run it as big and as loud as you can. This is how it's always worked. You publish something, and you try to get people to read it.

Illustration by Jim Cooke

The Concourse is Deadspin's home for culture/food/whatever coverage. Follow us on Twitter:@DSconcourse.