A 15,000-word piece about Tim Tebow is such a self-evidently bad idea that you would assume, not having read it, that this Sports Illustrated #longform offers something special to justify its claims on the time and attention of readers: fresh reporting, uniquely elegant writing, original ideas.

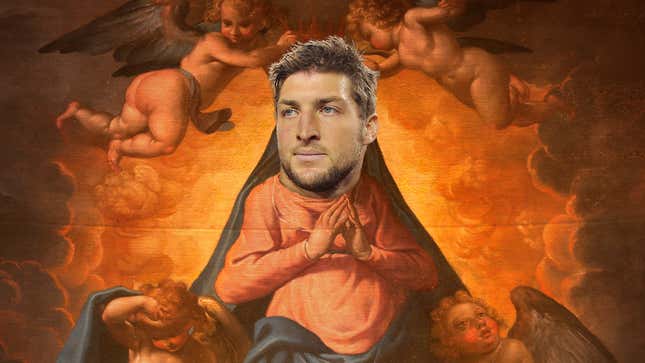

It doesn't, but give it credit for being not just bad but significantly bad, bad in a way that recapitulates everything that was terrible about Tebow's brief run of celebrity to begin with. The most interesting thing about "The Book of Tebow"—seriously, it's called "The Book of Tebow," illustrated with crosses, and broken up into seven sections that correspond to the seven capital virtues, one of which is misspelled—is just how inert it is, how little awareness it shows that the world has long since moved on. The new information on offer, mostly about how college coach Urban Meyer used Tebow as a policeman, could carry a piece perhaps a tenth this long; at its most lyrical, the prose reaches the level of a motivational poster ("Success can be earned, but every sunrise is a gift"), and if there are any ideas at all here, it would take a photomultiplier tube and a quantity of heavy water to find them. It is being sold on the premise that it exists.

Praise-baiting #longreads—rarely read, quite possibly not meant to be read, and laid out in formats that seem one twist of the dial away from a junior high school student's GeoCities page circa 1997—litter the internet like the bodies of dead satellites orbiting the Earth. This one is different, though, less because of its subject or its exceptional length—up there with the gospels, or "The Dead"—than because of its peculiar combination of ignorance and malice, and its general air of revanchist fervor. Seeking to explain Tim Tebow to the world, it just shows how little anyone really wants to engage with who Tebow is, or what he represents.

About 2,500 words into "The Book of Tebow," most of them about a game the Denver Broncos and the Chicago Bears played a few years ago, Thomas Lake, who wrote the piece, lays out his basic argument. He writes that Tebow became "a national Rorschach test" and that the fact that many Christians considered him "a hero, a paragon of virtue in an age of great sin" complicated judgments of his ability as a quarterback, which is so anodyne as to not be worth saying. He then follows on with this:

He was white, male, straight and Christian, so in 21st-century Western civilization you could assail him at no risk to your own standing among the politically correct.

It's hard to know where to start with this—it's a bonfire of all the strawmen—but past the appeal to pure racial grievance, and the use of "politically correct" as a term that has real meaning outside discussions of ancient intra-Communist debates, the fascinating thing about it is the way it sets up Tebow as a negative space surrounded by the bullying forces of secular liberalism. The implication is that no one assails him because they take him seriously—because they find his ostentatious religiosity ridiculous or his views on how God intervenes in the affairs of man vulgar, or even just because they're tired of the press going on at excessive length about a terrible football player—but rather because they want to position themselves as being in line with a certain set of social and cultural values, and do so without irritating anyone whose opinions they care about.

The irony here is that much of the piece's relentless awfulness is rooted precisely in its refusal to take Tebow and his beliefs seriously. As a minor example, take the capital virtues, the Latin names of which tag each section of the piece, presumably indicating that each is meant to relate to or illustrate its corresponding virtue. This not only renders the entire structure of the piece incoherent—in exactly what sense does a 1,500-word vignette about how Tebow played poorly with the New England Patriots have anything to do with caritas?—but raises the question of just what Catholic theology has to do with an aggressively Baptist football player.

Similarly, you have lines like this: "Another thing about grace: The more you receive, the more you can give." This is less a thought than a thought-like object; as vigorously as the various branches of Christianity disagree about grace, the gift of divine mercy is rarely spoken of as something that comes in measurable quantities, or that lousy quarterbacks are capable of bestowing. A line like this can't be taken seriously as anything other than a series of sounds, a way of signaling that Lake thinks about religion and takes it seriously, and so is on the side of Tim Tebow and against the secular liberal forces besieging him.

This insistence that words don't actually mean anything, that what matters is just that they do enough to signify one's cultural allegiances, is pretty much what Lake (generally wrongly) criticizes in Tebow's critics, and leads him into areas worse than dubious theology. In a section with the subhed "Did Tim Tebow Kneel At The Altar Of Political Correctness?"—tied, for some reason, to castitas—he writes this:

Preaching has gone out of style in America. So has telling people what they should or shouldn’t do, and telling them there’s only one way to get to Heaven, and telling them they need to renounce their old ways or they’ll probably go to Hell. Southern Baptists haven’t changed much. They mostly say and do what they’ve always said and done, but those things have become unfashionable in the Age of I’m OK, You’re OK. And being unfashionable is OK with some Southern Baptists. Certainly it is with the Rev. Robert Jeffress of First Baptist Church in Dallas. He’s not afraid to say, No, you’re not OK, and this lack of fear has made him a cultural heretic.

Like the riffs about the persecuted straight Christian white man and those who have enough grace that they can spare some for others, this is so nonsensical that it can only be taken as conveying an attitude, one sympathetic to the moral rigor of the Southern Baptists (if not their occasional excesses), and disapproving of '70s vintage California cokeheads clutching self-help books. The problem is that it isn't actually true. Robert Jeffress is a cultural heretic not because of his lack of fear, but because he's said that President Obama is paving the way for the anti-Christ, that gay people are an abomination, and that Islam and Mormonism are heresies from the pit of Hell. Reducing him to some Tebow-like abstraction is a way of avoiding what he actually believes and wants others to believe, and doing so diminishes him far more than critics do when they take him seriously enough to think that he means what he says.

Expecting any kind of real engagement with anyone's ideas or beliefs here, though, would probably be a bit much. Just as most of the words in this piece seem to serve no purpose but to vaguely signify, so does the piece itself. It's less about Tim Tebow than about the fact that it exists, and that the people who made it proudly practice #longform and so do their part to keep the guttering flame of journalism lit while dimly imagined people who have no respect for the craft of writing try as hard as they can to extinguish it. It's the inevitable result of an interlocking sequence of fallacies that raise form above substance or function, and make it so that if you lay down enough words, you don't have to say anything at all.

Image by Jim Cooke