Juanacatlán, Jalisco, sits on the slopes of lush foothills, 20 miles southeast of Guadalajara. To reach the town from the highway, you have to pass through its industrial neighbor El Salto, then cross the Río Grande de Santiago, one of Mexico's most polluted rivers, on a two-lane bridge adorned with a large overhead sign that reads in Spanish, "Thank you for visiting Juanacatlán: Land, forest, friendship and work."

Once upon a time, the swampy river gave Juanacatlán its identity, fertilizing nearby fields and filling the nets of local fishermen with shrimp. Tourists came from all over the world to see a waterfall known as the Niagara of Mexico. These days, the waterfall resembles a spilled glass of water dripping over a countertop. The river is more like a sulfuric moat, isolating the village of about 9,000 from sprawl and the slow creep of development; without it, Juanacatlán would be just another exurban blip on the far edge of Mexico's second largest metropolitan area.

It isn't postcard pretty, but Juanacatlán retains the feel of a pueblo. Horses clomp along the narrow streets and ancient men sit all morning on benches in the central plaza, talking or not talking as the mood strikes them. There is one big church, and no visible small churches. The stucco on the old, colorful houses is chipped and waterlogged. When it rains, as it tends to on summer afternoons, the water rushes down the sloped streets toward the river.

Everybody knows everybody—or else knows his cousin. One afternoon, I see a pickup truck with two bulls strapped standing up into the bed. The driver is leaning out the window and chatting up a police officer, who is lingering in front of the post office. Still, residents here say that Guadalajara isn't as psychologically remote as it used to be. The best jobs are across the bridge in El Salto now. Small businesses have given way to corporate factories. In the 15 years since Santos Álvarez brought his family to Juanacatlán with the idea of opening an ice cream shop, the outside world has crept closer than ever.

All great fighters come from somewhere, and not just in the sense that you and I come from somewhere. Early in their careers, boxers are defined by the place and circumstances of their childhoods as much as by their style and success in the ring. They wear flags on their trunks. Announcers belt out the names of their hometowns and countries as part of the pre-fight ritual. Julio César Chávez grew up in an abandoned railroad car in Sonora. Muhammad Ali was born to a sign painter in Louisville, Ky. Floyd Mayweather bounced between crack houses and boxing gyms in Grand Rapids, Mich. I'm in Juanacatlán because the youngest son of Santos Álvarez, Santos Saúl Álvarez Barragan, also known as El Canelo—the biggest fighter Mexico has seen since Chavez, and the latest in the long line of boxers to challenge the impenetrable Mayweather—grew up here.

Álvarez is the most popular boxer in Mexico by a longshot, and, according to Forbes, the country's highest-paid athlete who is not on a Major League Baseball roster, surpassing even the beloved Manchester United forward Chicharito. He is an unlikely ethnic champion who simultaneously draws eye rolls and misty-eyed loyalty from countrymen inside and outside the boxing establishment. He has red hair. He has never lost. His fights fill arenas and draw tens of millions of television viewers in Mexico. People here think he's got a real chance to beat Mayweather, but they also write him off as a feat of marketing who until recently has been coddled and protected by his handlers at Golden Boy Promotions and overhyped by Televisa, the network that shows his fights and recently announced that they would be turning his life into a telenovela.

Canelo is the youngest of seven boys and one girl. The oldest is Rigoberto, whom I meet in the family ice cream shop on a bright Saturday afternoon in Juanacatlán. Rigo is a dozen years older than Saúl, which still makes him one year younger than Mayweather. He scarfs down a strawberry paleta and invites me behind the counter to grab whatever I feel like. In the car, he tells me that he quit boxing because of what it does to your brain.

We talk at his aunt's, a two-story house on the edge of town. The living room is decorated with pastel Catholic art, mounted game, and family portraits. Canaries are chirping from a cage in some distant room. When Rigo boxed, they called him El Español, or The Spaniard. It's been a few years since he lost his WBA light middleweight belt to Austin Trout, but he still carries himself like a fighter, holding his shoulders back, bouncing off the balls of his feet, and walking through every doorway with a sense of ownership. That spirit extends to the interview. With almost no prompting, he launches into the Canelo story in a quiet, attentive voice. You can tell that he's done this before. You can also tell why the folks at Televisa want to make his brother's life into a telenovela.

The first episode might begin this way: A teenage Rigo watches Julio César Chávez on television and decides he has found his calling. He makes himself into a boxer by training behind his father's back, skipping out on computer classes to go to a gym in Guadalajara's historic center. Meanwhile, the family is shuttling between Guadalajara and nearby towns, trying hard to find a place where an ice cream shop will stick. They finally settle down in Juanacatlán. Rigo steadily improves. One day, after a year spent training and fighting in Tijuana, he pulls into the family driveway. He's 22 now, on the cusp of turning pro, and he has a gift for his youngest brother, a serious-minded redhead who is all of 10 years old: his own boxing gloves.

The minute young Saúl tries the gloves on, Rigo knows he has found something special. He relishes telling the story for what must be the thousandth time.

"I didn't have the slightest idea that hidden under that red hair there was an enormous talent," he says. "We put on the gloves, started to box, and when I began to see how he defended himself, how he moved his hands, his eyes, the way he began to throw punches with that courage, I swear it surprised me. And I said, 'God, I think this is a gift you've given to our family.'"

Rigo wasn't about to let that gift go wasted. He says that he saw all of it. He saw a future champion of the world. You can almost see the training montage playing out on the screen. After work at the ice cream shop, they would practice in the street in front of their house. They would run high up into the verdant hills outside of town, a pickup truck creeping behind them to illuminate the muddy trails. In three months, Saúl had his first amateur fight. A few dozen fights later, Rigo brought him down to a qualifying tournament for the national Junior Olympics. But the officials there didn't take them seriously. Three times, Rigo and Saúl were turned away.

"'From Juanacatlán? Where's that?' Nobody had heard of Juanacatlán, they wouldn't even bother to look at him." Rigo shakes his head. "They wouldn't even bother to look at him."

Finally, on the fourth visit, Rigo convinces a commissioner to let Saúl fight the best kid in his weight class. This commissioner was a nice guy, Rigo says. He was more understanding. "We'll fight, we'll win, and we'll leave," Rigo says he told him.

Saúl was just 13 years old, a bantamweight.

As Rigo tells it, Saúl dominated the poor kid in the first round, knocked him out in the second. Nobody applauded. The gym was silent. A redhead from a town nobody had ever heard of? A town that didn't even have a boxing gym? An official caught up with them in the parking lot and signed Saúl up for the Olympics. He won silver. The next year, gold. The next, at just 15, he turned pro.

After the interview, Rigo and I drive a couple blocks down to the old family home, which is mostly empty now and has a handwritten "For Sale" sign hung up out front. He spends a few minutes trying to start his truck parked in the driveway, a red Dodge with one of those hoods that protrude to make room for the massive engine. When it starts, the engine rumbles and draws the attention of some neighbor kids who walk by a couple times but don't say anything. Rigo grins like a proud daddy. He has a shaved head and wears loafers. His smile comes more easily than the scowls you always see fighters trying on for the cameras. He seems to get more pleasure out of being a businessman than a boxer; in that regard, he resembles his brother's promoter, Oscar de la Hoya.

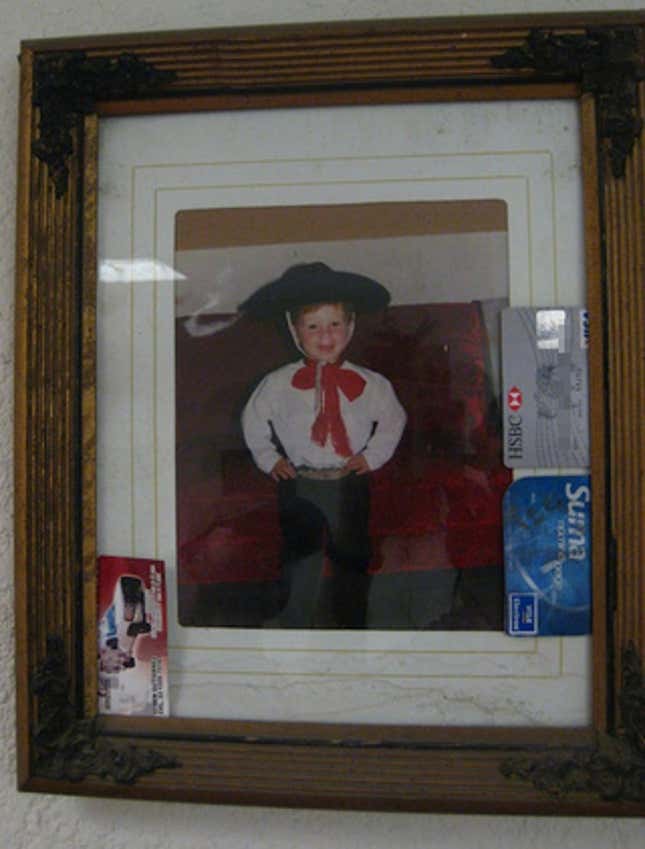

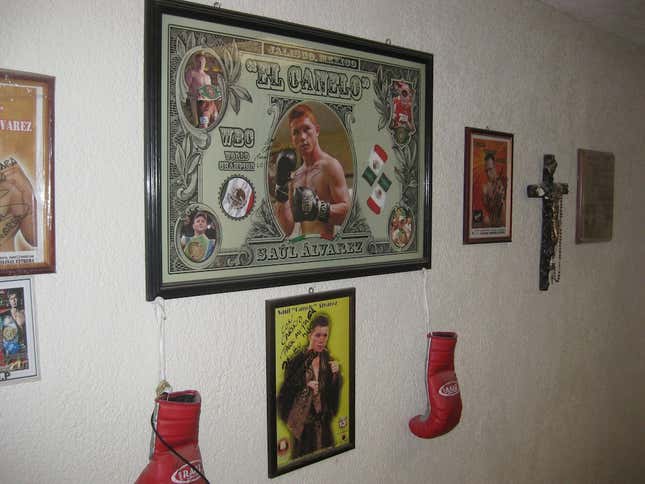

The house is mostly empty now, cool and stale. Scattered memorabilia, old newspapers, boxing gloves, framed photos. Most of the furniture is gone. Rigo shows me some childhood pictures of Saúl. Then he takes me on a tour of the town. This is where Saúl played soccer, this is where he had a carwash as a teenager, this is where we used to run. The guy in that torta shop sparred with Saúl when they were kids, but he didn't stick with fighting. We pass a recently opened boxing gym. "Those guys have nothing to do with us," Rigo said. So they're trying to capitalize on your brother's fame? "Yeah, but it doesn't bother me."

Canelo has moved past this place, it occurs to me . There might be some lingering emotional attachment, but the immediate family, including the daughter Canelo had when he was 15, lives in Guadalajara now. Even the ice cream shop is owned by their aunt. Rigo still comes around a lot. He serves on the town council and says he's trying to put a boxing gym in the community center. But the house is for sale. Saúl hasn't been seen here in years. His presence is confined to television and to whispers around town; it takes the form of reporters like me, coming to sniff around his past. But even from Guadalajara or Big Bear or Las Vegas, Saúl Álvarez remains the most powerful person in Juanacatlán. His importance here can be measured by the weight of his absence.

You might have noticed that Saúl Álvarez exists much the same way in this article. He is the person I am ostensibly writing about, but he is physically absent. When I tried to arrange an interview, his handlers at Golden Boy Promotions told me the following:

"Canelo has already scheduled interviews with serious publications, affiliates, and important media—Sports Illustrated, Time Magazine, ESPN Magazine, TV and radio as well as ESPN websites etc. which one needs for a Pay-Per-View mega event of this magnitude."

It's for the better, I think. The outward-facing Canelo is not a personality so much as a sum of his marketing; he exists in flesh and blood, but to most people in Mexico he is a character on television and in tabloids, a vessel for collective pride and anxiety. (The telenovela thing is not a stretch.) His main attributes—and this is confirmed by every single person I speak to in Guadalajara and Juanacatlán except his mother, who says "happiness"—are seriousness and quietness. Interviews with Canelo don't produce revelations; they hardly even manage to produce clichés.

Of course being quiet and serious and closely guarded is not an inherently bad thing. Canelo's job isn't to yap or lay bare his emotions. (If anything, his solemnity presents a marketable contrast to Mayweather, who talks impeccable shit as if by reflex, in long, perfectly formed sentences.) Canelo's job is to show up at promotional events and put his face close to Mayweather's and grimace. It is to be Canelo. Then, on Saturday, his job is to try and win.

My job is to chase him down, figure him out, and explain something about why he matters. But it's hard to chase down what amounts to a projected image, a hologram. One way to look at Canelo's short life so far is as an evolution from person into product. He was raised in Juanacatlán, and he was bullied because of his red hair and freckles, and he has seven older siblings. The story remains. And somewhere in there, under the layers of legal paperwork and media expectations and other people's braggadocio, so does the man. But in the meantime, Canelo the product has assumed a sort of placelessness. He resides in the corporate state that transcends physical borders; he is like all those trillions of invisible dollars that are constantly moving around the globe on wires from bank account to bank account—there is a disconnect between the idea of the thing and its actual physicality. It makes sense that ESPN's profile of him ahead of the fight is set largely on a private jet. This is the world in which he now lives.

The one place where the real Canelo exists, and forcefully so, is in the boxing ring. There's a reason he is undefeated. There's a reason why his fight against Mayweather is such big news. He's undefeated because he possesses the kind of preternatural boxing skills that make Rigo's story about thanking God for Canelo's talent sound only mildly, adorably far-fetched. The fight is such big news because unlike almost everybody who steps in the ring with Mayweather, Canelo actually has a chance to win.

Canelo has the kind of power that causes people to mistake him for a brawler in the mold of Julio César Chávez, but what defines him in the ring is his steadiness. He tends to apply constant pressure with hard, repetitive body shots; he's willing to mix it up and trade punches, but more inclined to keep his hands up, roll his shoulders, and defend himself. Canelo may not have Mayweather's quickness or fluidity or genius, but one thing I hear over and over again from boxing people who have been around him is that he's smarter than he gets credit for. He's a student of his sport, capable of making adjustments mid-fight.

Then again, when I ask Rigo about his brother's strategy, he shrugs his shoulders and smiles and says, "Golpearlo." Hit him. The general feeling in Canelo's camp is that Mayweather has never faced anybody this strong.

For most of his career, "hit him" has been all the strategy Canelo's needed. When he outgrew boxing practice in the front yard in Juanacatlán, his brother brought him to Guadalajara to train with Chepo Reynoso and his son Eddy in a tiny gym called Gimnasio Julian Magdaleno in an unremarkable working-class area called Sector Libertad. I show up there on a Monday afternoon. In the tradition of boxing gyms everywhere, there are three guys working out and about a dozen, mostly teenagers, sitting around bullshitting. Every inch of wall space is covered with murals, newspaper clippings, pictures of Canelo, of Ali, of Jesus Christ. The heavy bags are wrapped around with so much duct tape that you wonder if there was any leather there in the first place.

The kids at the gym are quietly optimistic about Canelo. Most come from the neighborhood, and even though they're working out where he worked out, and even though they've shaken his hand, watched him spar and skip rope, I get the sense that they still feel a million miles away from his world. Instead of saying much about the fight, they defer to their trainer, whose name is Marcelo Lopez. Lopez had a short pro career. He's known Canelo since back before Chepo and Eddy gave young Saúl the nickname ("canela" is Spanish for "cinnamon").

When I ask if he's surprised that Canelo has reached these heights, Lopez shakes his head. "He had a physique that was out of the ordinary," he says, and goes on to tell a story about how a teenage Canelo calmly held his own with a fully grown Javier Jáuregui, who was not far removed from an IBF lightweight title belt.

In the cramped gym, surrounded by trophies and memorabilia, I find myself starting to believe for the first time in Canelo Álvarez. Maybe it's the smell of sweat and Vaseline and the fact that everybody around me is so serenely confident and yet so far removed from the Golden Boy/Showtime/Televisa hype tornado. Maybe it's because before showing up I hadn't realized just how good, just how serious they are about boxing in Guadalajara. Before, I thought of Canelo as some sort of mythological character, sent by his village to defend them courageously but futilely against a wrathful and petty god; it felt almost sacrificial to match him up against Mayweather. I still don't know if he's merely a big fish in a smaller ocean. Nobody will until the fight. But faith is contagious, and here I am thinking maybe a knockout is not so farfetched.

"In the end, in boxing, it's the punches that matter," says Lopez. Boxing is a simple sport and, perhaps because of that simplicity, an endlessly complicated one. Just because something has never happened before doesn't mean it can't happen now. So far, those punches have carried Canelo a lot farther than most people go; farther than his brother Rigo or Javier Jáuregui or Oscar Larios or any other of the world champions who have trained here. In fact, they've carried him out of the building entirely, to a brand new gym a dozen blocks away with high ceilings and shiny floors and mean dogs keeping guard on the roof.

The 12 blocks between Gimnasio Julian Magdaleno and Escuela de Boxeo Saúl Álvarez are, in and of themselves, fairly dull. You pass some convenience stores and some soccer fields and many unassuming apartment buildings. But the metaphorical distance is greater. The gym is a physical manifestation of Canelo's arrival as an international superstar fighter. It opened in June 2012, about a month after he beat Shane Mosley. Now when a boxer in the Reynoso stable has outgrown Julian Magdaleno, he or she is sent here, where there are more fighters actually training but zero people socializing. If not for the Canelo-themed décor—including a gigantic wall-sized poster advertising the Mayweather bout—Escuela de Boxeo Saúl Álvarez could be anywhere. It has the calculated sterility of every MMA or CrossFit gym in every city.

The Starbucks where I meet Canelo's mom and sister could also be anywhere.

People say that Guadalajara is the most Mexican city in Mexico, capital of Jalisco, the state responsible for tequila and mariachi. If that's true, then the new development Andares is the least Mexican place in the most Mexican city. Far removed from the day-to-day lives of the people who adore Canelo, Andares is the ultimate corporate non-space: perfectly in line with the shiny opulence of contemporary boxing, it is the physical manifestation of the idea that newness equals status, Guadalajara's most exclusive shopping mall, residential complex, and business center all rolled into one complex.

We sit outside on some luxurious patio furniture. Music pipes in, loud enough to cancel out the nearby traffic but not quite loud enough to be heard. None of us orders anything and nobody seems to mind. Saúl's mom, Ana Maria, and his sister Ana Elda are both excited to talk about him. They tell stories about what a feisty and caring child he was, what a mature young man he has become. Young Saúl liked to ride horses and hang out at this farm and always smelled terrible. He got in trouble once for bloodying the nose of a much older boy. At one point, Ana Maria catches a glimpse of a newspaper with Saúl's face on it. She tears up. "There's my beautiful son. I say that with great pride. My baby."

Ana Maria and Ana Elda could be any mother and sister in Mexico, inordinately proud of her son or brother's accomplishments. It helps that their own lot has improved, but it doesn't necessarily matter. I ask if their lives have changed much since Canelo became a phenomenon.

"Considerably," they say.

What about Saúl? Has he changed?

"He's still the same."

One possible explanation for the fact that Canelo hasn't been back to Juanacatlán lately is that many people think his brother Victor killed a guy there last year. The story goes that Victor Álvarez and Luis Enrique Gama Partida had some drunken words over a girl down by the river. Words turned into fists, and fists turned into gunshots. If it sounds like a Bruce Springsteen song, well, that's because it's a lot like a Bruce Springsteen song. Victor disappeared for a while; he was even called a fugitive in news reports. (Many papers and channels covered the story, with the notable exception of Televisa). Then the charges disappeared. The news reports disappeared, too.

It's not hard to draw conclusions about how those charges disappeared. The family of the victim accused the state attorney general of Jalisco of offering privileges to Victor. The A.G. said he offers privileges to no man and would not hesitate to pursue the case. But nine months later, Victor is with Saúl at training camp in Big Bear, and Juanacatlán is still whispering about the case, which remains unresolved.

Nobody I speak to in the village doubts that Victor had something to do with Gama Partida's death, though there are various theories about the exact sequence of events. Neither does anybody seem surprised by the fact that no charges have been filed. This is life in a small town in Mexico, which closely resembles life in a big city in Mexico. It doesn't matter exactly what happened before and after the murder. The stunning thing is the quiet force with which power is wielded, or at least assumed to be wielded, and completely accepted as the status quo.

For example: I ask one guy what he thinks of the Álvarez family. "As athletes or as people?" he responds. After we talk a little about the murder and the town and the brothers, he asks me not to use his name. "They'll pay me a visit," he says. When I ask him if he's rooting for Canelo in the fight with Mayweather, he says of course he is. But he also thinks the fight is fixed.

None of this should actually prevent Canelo from returning to visit. After all, he is not accused of anything himself, his brother Rigo is still a prominent citizen, and his relatives still live here. If anything, he would be welcomed back as a hero. Few people from anywhere, much less a small town in Jalisco, reach the heights he has in any field, much less a highly public field like boxing. (I did hear rumors that he comes secretly, in the middle of the night, to party with his buddies in the hills.) The real reason Canelo hasn't returned has less to do with the town than with his own ascent. Juanacatlán might draw much of its identity from its most famous son, and its residents might still be susceptible to his influence, but Canelo Álvarez has transcended geography.

Well, not quite. Canelo might exist in a world of Ferraris and armed bodyguards, but the ring announcer will still introduce him on Saturday as the WBA and WBC light middleweight champion from Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. The family is there, the gym is there, even the ice cream shops are there. Rigo and their dad Santos have eight of them. The short-term plan is to rebrand the shops in order to capitalize on the family name. The long-term plan is to move out of ice cream all together, and into boxing. I meet Rigo in front of one of the shops in Guadalajara's main bus station. He's texting on two cell phones at once.

Rigo sees himself as a promoter, he says, and the Álvarez family as a boxing dynasty. He's already started a company called Canelo Promotions, which is modeled off of De La Hoya's Golden Boy, leveraging one fighter's fame to attract talent and investors. (He hasn't asked his brother for permission to use his name; he feels like he doesn't need it.)

"Things are moving forward," Rigo says. "For example, the family, the way I see it, our future, we're going to be a family, beginning with myself, the pioneer, we're going to be a boxing family. We're going to transcend in this. Maybe one day a nephew or a grandson will be a champion of the world."

Meanwhile, the current champion in the family cruises above all this on a cloud, or a private jet. He may upset Floyd Mayweather, and he may not. His countryman Márquez, the Mayweather victim who thinks he won't, has also said it doesn't much matter: "If Canelo wins, it is a great triumph for Canelo and for all of Mexico," Márquez said back in May. "If he loses, he still wins because of the experience he gains from the fight."

A Guadalajara sportswriter I spoke to put it another way. All Canelo has to do, he said, is not embarrass himself. If he fights a hard fight, he remains a hero. The telenovela is already written.

Eric Nusbaum lives in Mexico City. He is a co-founder of The Classical and his work has appeared in Deadspin, Slate, Outside, The Daily Beast, and The Best American Sports Writing. You can reach him on Twitter @ericnus. Top image by Sam Woolley.