The biggest chess story of the year is uplifting—and bogus.

On May 31, the Baltimore Sun ran a feature on a seventh-grader whom the paper identified in the headline as a “national chess champion.” According to the Sun’s story, the 12-year-old learned to play the millennia-old board game in a local barbershop and, while representing Roland Park Elementary and Middle School, a K-8 public school in the city system, came back from a Tennessee tournament earlier in the month as “Baltimore’s first national chess champion.”

America is normally apathetic to chess news; so is Baltimore, despite its long history as a chess town. (The University of Maryland Baltimore County was among the first colleges to give full scholarships for chess, and has perennially been among the strongest collegiate chess programs in the nation. The last two women’s national champs—international master Nazí Paikidze and Sabina Foisor, the reigning titleholder after taking Paikidze’s crown last month in St. Louis—are UMBC alums.) The story about the Baltimore barbershop kid turned national chess champion, though, went viral.

The Sun ran at least two more pieces on the 12-year-old, always identifying him as a national chess titlist. The Washington Post ran the Sun’s story on its site the same day. Essentially every Baltimore news outlet, from online publications to network tv affiliates, told the tale of the homegrown underdog conquering the country. The Baltimore Orioles invited the kid to the clubhouse for a media event last week, which MLB publicized, making it a national story. NPR did a segment on the “first national youth chess champion from Baltimore” on Weekend Edition. The 74, an education reform group, was one of many school-centric organizations that promoted the news about Baltimore’s “1st US chess champ.” (The Root, a sister publication of Deadspin, was among the outlets who aggregated the Baltimore Sun’s work, posting two separate stories about chess’s new national champ.)

Great story. Never happened.

“The kid didn’t do anything wrong,” says Francisco Guadalupe, director of events for the United States Chess Federation, “but he’s not a national champion. To say that is incorrect.”

The tale of how reality got checkmated by fiction in Baltimore is not nearly as cinema-ready or heartwarming as the story the Sun told. After well-meaning, chess-naïve grownups turned an unwitting kid into a media star by making him out to be something he wasn’t, nobody who knew the real score—including the news outlets who were told the facts after the fake news about a national champion broke, and chess officials who knew the whole truth the whole time—was willing or able to stop the story’s spread. It seems that the truth, which was plenty heartwarming in its own right, just wasn’t interesting or useful enough to anyone who counted.

“He’s not a K-8 national champion.”

It all began last month at the Supernationals, an event sanctioned by the USCF, directed by Guadalupe, and billed as the largest scholastic chess tourney in the land. According to the USCF, 5,575 school kids—kindergarteners on up from all across the land—played in the tournament, which was broken up into groups by age and chess rating. The 243 top competitors in eighth grade or lower played for a national title in the K-8 Championship category. The Championship grouping, per Guadalupe, had one player rated by the USCF as a Senior Master (a player with a rating of 2400 or above), at least six National Masters (2200+), 21 Experts (2000+), and dozens of Class A, B, and C players.

The Baltimore kid chose not to enter the championship grouping, Guadalupe says, though by age he was eligible. He’d played in 13 USCF tournaments since 2014 and had a player rating of 980, which Guadalupe said is regarded in the chess world as a Class F rating, a beginner classification. Pitting beginners against masters in a chess tournament would be as unwise as throwing yellow belts up against black belts in a martial arts competition, so in scholastic tournaments, organizers often have novice brackets. At the Supernationals, in the Baltimore kid’s age group, there was such a beginners event, called the K-8 U1000 group and limited to players with a rating below 1000.

The Baltimore kid, Guadalupe says, “made the correct choice” by foregoing the championship bracket and instead entering the U1000 event. That spared him matchups against masters and guaranteed games only against players also rated as beginners. According to Guadalupe, choosing the U1000 event also meant he wasn’t competing for a title; only those in the Championship bracket were eligible for the national championship. The U1000 entrants were competing, essentially, for 244th place in their age group.

Thriving against fellow beginners, the Baltimore kid defeated all seven opponents he faced, and was the only player in the U1000 round-robin to go undefeated. The performance got him a trophy—but, again, no national title, says Guadalupe.

“None of the kids who played in the under-1000 could compete in the Championship section,” Guadalupe explained. “It would not be competitive for them to play in that section.”

The USCF news page had an extensive writeup of the final Championship rounds under the headline “Sunday Is For Champions.” The summary includes news about the K-8 Championship bracket, reporting that it was won by a player from Connecticut who learned to play in the Netherlands and whose 2412 USCF rating already has him as a senior master, and specifically calls that kid “national champion” in the age group. There’s no mention of the K-8 U1000 bracket, or any mention of the Baltimore kid, in the USCF tournament summary.

“Not to diminish the accomplishment of [the Baltimore player]—he won all his games, the only one who did that, but in a low division,” said Guadalupe. “He’s not a K-8 national champion.”

“Some say there is a time to lie and others will say a lie is still a lie.”

The truth about what actually took place at the Supernationals should have been enough for the Baltimore media. A local kid leaving the barbershop where he learned to play and beating lots of fellow novices from across the country in a chess extravaganza with well over 5,000 entrants has the makings of a fine feature story.

For whatever reason, though, the real tale wasn’t impressive enough for some adults back home. And so through no fault of the young player, local folks made up a national championship out of thin air and handed it to a kid who’d only beaten fellow beginners. Suddenly, it was as if the kid who finished first in a Fun Run was being hailed as a Boston Marathon champion.

The story began going off the rails on May 15, a day after the Nashville tournament, when Alec Ross, a Baltimorean who recently announced himself as a candidate for governor of Maryland, tweeted out congratulations to the local player “who just won the National Chess Championship.”

Ross did not respond to requests for comment for this story. But a source from his campaign told Deadspin that Ross’s son also plays chess on the Roland Park squad that traveled to Nashville, and that the candidate was merely repeating “National Chess Championship” after hearing it from another team parent, never expecting the tweet to go viral. Ross’s Twitter account, alas, boasts 365,000 followers, and the errant tweet reached and was retweeted by Baltimore thinkfluencer and activist Deray McKesson. The Undefeated, ESPN’s black-interest site, ran Ross’s tweet as a graphic on its site a day later. Soon enough Ross’s original tweet had almost 2,000 retweets, and Baltimore was buzzing about its “National Chess Champion.” Mayor Catherine Pugh scheduled a medal ceremony at City Hall to honor the new national titlist.

Then, on May 31, the Sun put the kid on the front page, and the paper’s erroneous Supernationals story—which was also tweeted out by McKesson and U.S. Senator Chris Van Hollen, among many others—went into high gear on the misinformation superhighway.

Readers who commented on the Sun’s site and posted on the Twitter feed of Luke Broadwater, the reporter who wrote the original story, tried alerting the newspaper and the writer of the mistakes.

Despite their efforts, the Sun issued no correction. But at some point after commenters on Reddit and elsewhere accused the Sun of misleading readers, the paper added a clause to Broadwater’s story, saying that the kid had not played “in the event’s highest division.” All the national chess champion references—really the only thing wrong with the story, but also, as presented, its reason for being—were left alone, even in the headline. The Sun’s addendum was not only too little, it was also too late. The story was republished by the Washington Post, with all the errors but without the slightest caveat. And soon enough the story was aggregated all over the internet.

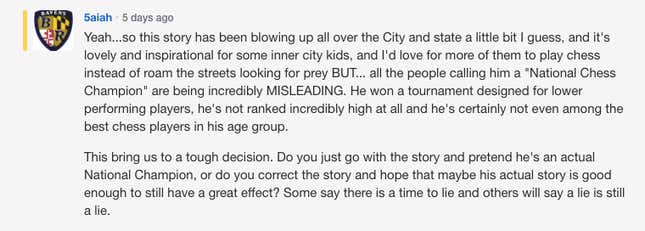

Some folks who knew the truth, while acknowledging that the fake story about the new national champ was hard to resist, tried to stem the false tale’s spread. A poster on Bossip, for example, expressed a natural conflict between being happy to see a kid who deserved it being celebrated and knowing he was being celebrated for something he didn’t do, rather than what he did:

A Reddit commenter to a thread about the Sun’s chess piece seemed sincerely bummed that an article he loved had collapsed under inspection. “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story,” wrote drunkmasterflex. “I was happy to read about something other than murder and corruption out of Baltimore for a minute.”

But in the end, the facts were no match for the feel-good.

“It just got taken out of proportion.”

Susan Polgar, a former chess wunderkind and long one of the most active advocates for scholastic chess, lamented that an inaccurate story got scads more notice from the mainstream press than real and real good news on the American chess scene. Polgar pointed out that the Baltimore story got more media hype than the U.S. national team did for winning the gold medal in last fall’s Chess Olympiad, even though that marked the first time in the history of the nearly century-old biennial event that an American squad finished first when the Russians or Soviets weren’t boycotting. She was also bummed that the faux title tale got more coverage than the actually amazing ascension of Wesley So, a 23-year-old from Minnesota who is now ranked second in the world, behind only world champ Magnus Carlsen.

“That’s sad,” Polgar says. “On one hand, I’m very happy for the young man that he got all the attention and publicity, and that it’s a big thing for him and his city. At the same time you have to put it in perspective: It’s not being a national champion. It just got taken out of proportion.”

The dissatisfaction that chess’s powers that be feel about the amount of publicity their favorite pastime gets explains why nobody from USCF even tried to correct the Baltimore story. Guadalupe admits that the federation was aware that a false narrative of what took place in Nashville had taken hold, but nobody wanted to get in the way of the story as it spread.

“The more articles that appear in the newspaper in Hometown, USA, the more good publicity that we get for chess,” says Guadalupe. “It’s not accurate, but we’re not going to call each and every family and newspaper and say, ‘That is not correct!’

Meanwhile, the Connecticut kid who was the actual K-8 national champion got namechecked in the third paragraph of the Boston Globe’s chess column. That’s it. The Red Sox or any mayor never called.

Broadwater did not respond to Deadspin’s requests for comment; Baltimore Sun city editor Eileen Canzian said the paper was sticking by its stories about the chess kid, national chess champion references and all.

“The heart of the story is that a little boy in a barbershop learned how to play and stay off the streets and is doing well,” Canzian told Deadspin. “That’s the essence of the story. Are you saying that’s not right?”