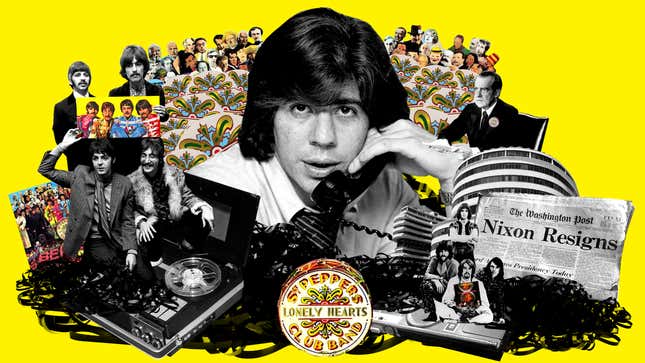

Watergate and the Beatles are multimedia evergreens.

Just last week alone, for example, the History Channel commissioned a documentary series on the scandal that brought down a president, and Variety reported that yet another feature film about Watergate, The Silent Man, is now scheduled to hit theaters in September. And on Friday, special editions of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the 1967 album that brought down the pop single, were re-issued to celebrate/exploit the 50th anniversary of the disc’s original release.

Carl Bernstein had ties to both. His work at the Washington Post during Watergate was what justifiably made Bernstein a household name. But what’s not so well known is that before he became a reporting legend, Bernstein was a critic at the newspaper. A pop critic. And Sgt. Pepper was among his first critiques.

Pop criticism was a new realm. Rock and roll was first noticed by the mainstream press, after all, only after 21-year-old Elvis Presley showed up on The Ed Sullivan Show in September 1956. The Post didn’t even have a full-time pop critic when Bernstein was hired in 1966 and assigned to cover the counter-culture movement. On that main beat, he filed stories on such things as a turf war between aging twentysomething hippies and up-and-coming teen hippies on a parcel of land in Rock Creek Park, and a high-profile D.C. drug bust where police seized 20 pounds of marijuana on property owned by John Steinbeck IV, the famous guy’s son. (Steinbeck got acquitted of running what the authorities termed a “dope pad.”) But, Bernstein really wanted to write about rock and roll, and occasionally the paper let him.

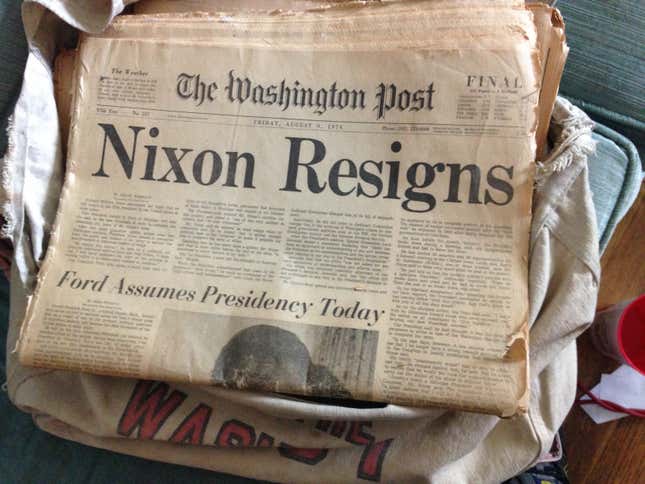

The Beatles and Bernstein were big deals to me. The first records I remember were my parents’ Beatles records; “I Feel Fine” was the first rock song that wowed me. My first job was as a paperboy for the Washington Post starting when I was 11 years old. That was the summer that Watergate climaxed. Watergate made journalism very cool—Beatles-cool, even. I still have my copy of the “Nixon Resigns” edition, the most momentous front page in the history of newspapering, and I keep it in the Washington Post bag that I used for my six years of delivering the paper. I’m pretty sure having that job in that era in my formative years factored into me ending up typing for a living.

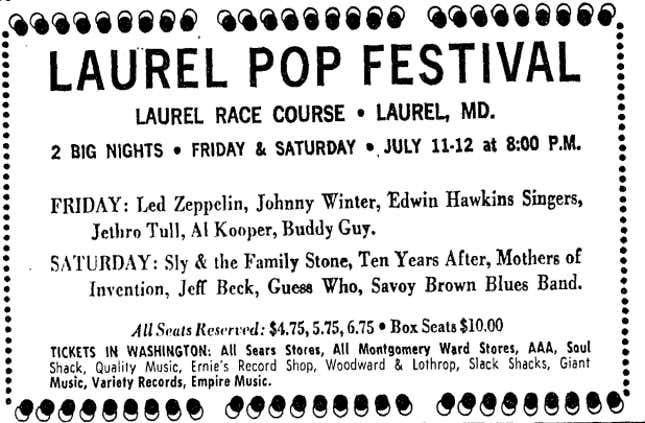

I first learned Bernstein wrote about rock around the turn of the century, when somebody sent me an old and very entertaining Post clip having to do with the Laurel Pop Festival, a big outdoor to-do in July 1969, about one month before Woodstock as outdoor rock extravaganzas were becoming the big thing.

I was joyously surprised to see Bernstein’s byline on it. Not long afterwards, I dove into the Washington Post archives to see if there were other Bernstein treasures that could be unburied.

There was lots to read. He wrote up the Byrds, Janis Joplin, Donovan, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Peter, Paul & Mary when each was at the top of their game. I loved them all; every hip clip showing that the guy who brought down a president was really out there, man!

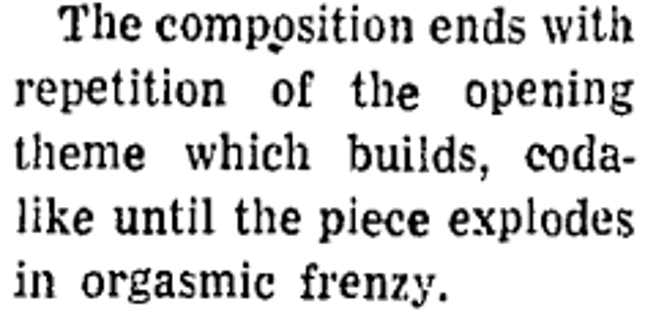

But I learned pretty quickly that history had done a real number on some of his critiques. For example, he loved Iron Butterfly, a proto-Spinal Tap combo, and in a 1969 write-up he went ga-ga praising the band’s 17-minute epical opus, “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida”:

“In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” is held together by a long, erotic drum solo that moves contrapuntally with clapping from the audience. The drum solo is bridged to a driving bass line on top of which is layered a dark organ passage and siren-sounding guitar. The combination works perfectly, allowing each element to be heard on its own and as a whole. The composition ends with repetition of the opening theme which builds, codalike until the piece explodes in orgasmic frenzy.

Contrapuntal orgasms aside, Iron Butterfly is now conventionally accepted as being among the worst rock acts of all-time, and “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” finds a place in lots of polls of history’s worst tunes.

Bernstein’s coverage of the Laurel Pop Festival has also aged poorly. He destroyed “the British would-be blues groups” on the bill, which included Led Zeppelin and the Jeff Beck Group, citing the “disappointing guitar work” (of Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, respectively) and accusing the bands’ lead singers (young unknowns Robert Plant and Rod Stewart) of being “engaged in a latter day version of black face.”

Oh, well.

I called Bernstein up after my archive dive to ask about his critic days. He told me he had loved rock and roll from its infancy—he said he saw Buddy Holly play live, for crissakes—and was excited that the Post gave him the opportunity to see and write about rock records and concerts in a golden age of the genre. He said he eventually grew to see his original assessment of Led Zeppelin as flawed, but meant every word he wrote as he wrote ‘em.

“I get Led Zeppelin now. I love them,” he told me. “But, boy, did I not get that band then.”

Yet he couldn’t hide his shame when I read back to him some of his Iron Butterfly puffery. “I didn’t like Iron Butterfly, did I? Oh, God no!” he said. “’In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida’? I said I liked ‘In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida’? Oh, please!”

But nothing about his piece on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is worthy of contrition or shame. When given his first chance to mull Sgt. Pepper’s place in the cosmos all those years ago, Bernstein nailed it. You can look it up. From his story, which ran in the Post’s June 18, 1967 edition under the headline “There’s Never Been Anything Like the Beatles’ New ‘Band’”:

In their latest album, the Beatles have managed to create a musical infinity through a miraculous metamorphosis of dozens of Eastern and Western musical ideas, some centuries old, others from our own era and more than a few from the future.

When combined with John Lennon’s perceptive lyrics (and honed wit), the Sgt. Pepper metamorphosis becomes a wildly contemporary continuum—structured pop music with a beginning, middle and end linked by riotous sounds, words, colors, images and musical tension. It is a bit fantastic, and certainly unprecedented.

Not everybody got it right. Richard Goldstein of the New York Times was never allowed to forget the haymakers he threw in his Pepper review, in which he cited an overall “shoddiness in composition” plaguing an “undistinguished collection of work.” And while Bernstein was using his out-there-est prose to warn readers that they were about to be hit by something totally new and different and utterly fabulous—all of which holds up just swell—the Sgt. Pepper write-up that ran in the Post’s rival daily, the Washington Star, now shows us how much growing up the rock criticism field still had to do a half-century ago:

To add to the furor over their new album, Paul admitted taking LSD. Incidentally, you might check the lyrics on one of the album’s cuts, “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”–then glance at the title of the song– pick out the main words “Lucy, “Sky” and “Diamonds”– the initials spell out LSD.”

President Richard Nixon’s minions broke into the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters at the Watergate about five years after Bernstein nailed the place of Sgt. Pepper in history and two years after the Fabs broke up. (Iron Butterfly drummer Ron Bushy said Ringo Starr confessed to him after the big breakup, but before the big break-in, that the drum solo on “The End” from the last album the Fabs ever recorded and the only solo Ringo ever put to vinyl, was stolen from...“In A Gadda Da Vida.” Yup, a Beatle and Bernstein were of like minds.) Bernstein once told me that in between the Beatles review and his partnering with Bob Woodward to become the Lennon/McCartney of investigative journalism, he got peeved at the Post because the paper had hired its first full-time rock critic, and didn’t give him a shot at the gig.

So he applied for a job at Rolling Stone magazine, far and away the major leagues for music writers at the time. But he never made it there.

What happened? I asked him.

“Watergate happened,” he said.

Oh, right.