Originally published in Inside Sports (June, 1980), this story appears here with permission.

Ralph and Steve, chinchillas, live in window cages in New York’s fur district, just down the street from Gleason’s Gym. Steve is wrapped around a stick, training for the day he’ll occupy the same position on mademoiselle’s shoulder. Ralph is asleep, unaware of the excitement a few doors away.

Standing in front of Gleason’s a quartet of three-piece suits, talking about a jump in the Dow, is crowding a kid whose T-shirt sleeves are rolled to display a snake-and-knife tattoo. The front of the line is about 20 people away, all waiting for a glimpse of Roberto Duran, the fighter with the burning eyes, the former lightweight champion challenging Sugar Ray Leonard’s welterweight title.

Don Turner, a local trainer, is standing inside the front door at Gleason’s, helping out today because of the size of the crowd and because he can extend an open palm and say, “One dollar.” Something about the tone of his voice, and the size of his palm, has produced the admission price every time. So far.

“One dollar.”

“Why I got to pay?” The visitor is staring at Turner’s shoulder.

“Everybody pay today. Duran sparring.”

“I just want to use the phone.”

“Okay.” Turner points to the wall. “Phone’s over there. Just gimme a dollar.”

Turner passes the bill to Sammy Morgan, a heavyset man sitting behind a high counter. Sammy doesn’t like to say how many dollar bills he’s holding. Maybe 100, maybe 125. He will say how many people paid on the same day a week earlier, when Duran wasn’t there. “We got three,” Sammy says.

Duran spars in the ring at the far end of the gym, almost directly under a narrow balcony. Most of his audience is pressed against the railing. Others stand on the stairs leading to the balcony. There’s a crush inside the empty ring near the door, some perched on the ropes for a better view. “Off the ropes,” is another thing Turner says. He has more success with “one dollar.”

Latecomers fill the aisle between the rings and the wall. When Duran finishes sparring he jumps rope. His fans push back to give him room, but every few seconds the jump rope slaps against somebody’s shirt and drops. Duran glares. “Fa chrissake,” yells co-trainer Ray Arcel, “get away from him.” Impossible. Packed so tight, the spectators can barely move. Duran folds the rope. The workout is over.

“He likes New York, he likes to train here,” says co-trainer Freddy Brown, “but how can he?” Arcel, 81, and Brown, 71, are the wise old heads who have honed Duran’s skills for the past eight years. Arcel, when he’s not screaming, sounds like the chairman of a college English department. Brown is a white-haired man with a nose that resembles a low flush in clubs. His sentence structure is equally dazzling.

“These people don’t let him train,” Brown says. “They bother him too much. They don’t let him work. Not that they don’t want to let him work. But they want him. They’re right on top of him. They want to hug him, they want to pat him on the back, they want to shake his hand, they want autographs, they want pictures, they want this, they want that. It interferes. He likes it but it stops him from working. He gets into mischief. That’s why we cut his workouts in New York.”

Soon, they’ll be hiking to Grossinger’s, the Catskill Mountains resort that’s two hours from the city. Grossinger’s and Gleason’s: The only thing they have in common are the chinchillas. “Sure, the mountains are better than here,” Brown insists. “Anything’s better than here. But the best place was in Panama. Where the army trained. There was nobody there. Nobody. I had to sleep in a bunk. Duran too. Everybody, the sparring partners, we slept in bunks. The food wasn’t too good, but ya ate it like the army eats it. They don’t give ya nothing good, the army. Duran don’t care. If it’s good steak or bad steak, he’ll eat it. Food, to him, is nothing. He don’t ask for this, he don’t ask for that. The reason his weight goes up now and then is that he cheats. At night, he’ll go someplace, grab a soda, this and that, and come back the next day and he’s heavier. We have it out. So the next day he won’t do it. And the following day he won’t do it. Then he cheats again. In Panama, with the army guys, he got on line in the morning and ate eggs, whatever the army got. Nobody bothered him. He got plenty of work, plenty of rest.”

It’s just before the move to Grossinger’s, and it isn’t the best of times. For one thing, Duran doesn’t have any clean socks.

“The socks are in my car,” Luis Henriquez says. Henriquez, an honorary vice-consul of Panama based in New York, represents Carlos Eleta, Duran’s millionaire manager. He makes calls from a desk in promoter Don King’s office. (“My connection to the third world nations,” King says of Henriquez. Exactly how another boxing promoter, now among the missing, once described King.) Very soon, Henriquez says, he’s planning to become an independent, representing fight managers, finding the best deals. I first met Henriquez when Duran won the lightweight title from Ken Buchanan in 1972. He had a question then: “Tell me something about your country. How is it possible that you can kill a man here, plead temporary insanity and they let you off? But write one bad check, goddamn, and they send you to jail.”

Henriquez is driving his brown and tan Rolls-Royce to Duran’s hotel. His conversation is still concerned with money; his, Duran’s. “He owns an apartment building in a middle-class neighborhood in Panama City. With the money from this fight he wants to buy a building in a better neighborhood. Money’s what this game is all about. Too many guys had it and lost it. Stupid. This fight is important because it can put him, financially, where he ought to be. Right now, he don’t have as much as he should. He’s good-natured. He gives too much away. He sees what I got, this car, my clothes, and it used to make him angry. Carlos Eleta finally told him, ‘Never mind what Luis does with his money, he’s working for you.’ He believes that now. We’re buddy-buddy. Those socks I got in my trunk, they called me up and said he needed them. Okay, no trouble, I’m bringing them.”

He glances at his watch. He’s late. “We’re going to go through a few red lights. Don’t worry… I got a diplomatic license.” I’m not worried. Somehow, I’ve always known that my last ride would not be the delivery of a half dozen pair of athletic socks to Roberto Duran.

Duran is sharing a suite at the Mayflower with his 18-year-old brother, Armando, and an uncle, Socrates Garcia. Duran has the bedroom and the two others use the sofa bed in the sitting room. When Henriquez arrives, the three family members are sitting up in Duran’s bed, watching a Spanish-language channel. Domino tiles are scattered on an end table. A pair of athletic socks is draped across a lampshade, drying. Henriquez presents his gifts, removing them from the bag with a magician’s flourish. The fighter isn’t amused. Henriquez introduces me. The look on Duran’s face says he is happier to see the socks.

Almost nine years ago, when Duran made his first appearance in New York, I covered his fight against a journeyman named Benny Huertas. Duran blazed out of his comer and finished Huertas in about a minute. He was awesome. But I couldn’t help noticing that he neglected to shower after the fight. “Duran hardly worked a sweat,” I wrote, “and a good thing too, because he didn’t bother to shower.” Duran, I found out later, hated the line. “I reminded him,” Henriquez is saying now, “that you were the guy who put in the paper he don’t shower. He remembers you.”

And I remember a Duran who destroyed opponents with animal ferocity, the quicker the better. Seventy-one fights, 55 knockouts, 24 in two rounds or less. His one loss, to Esteban DeJesus eight years ago, was avenged twice in title bouts, another pair of knockouts. He made a dozen defenses of his lightweight title. Eleven knockouts. One of them sent Ray Lampkin to a Panamanian hospital. “If I trained,” Duran said, “I would kill him.” One sweet man.

Suddenly, when he took on the 147-pound division in 1978, the knockouts were harder to come by. Duran seems to have lost that ability to overwhelm an opponent. He fought three times last year, winning each bout only after the scorecards were tallied. His followers point to his last two fights, knockout victories, to make the argument that Duran is still a hard guy. But he was fighting passport pictures—Josef Nsubuga, from Uganda, and Wellington Wheately, the Ecuadorian.

Does it bother him that he isn’t putting away the best people? “No,” Duran says. “Why should it? Let them think what they want. What can I do if the other man runs?” The truth is, lightweights run even better than heavier fellows. Running was never a wonderful strategy against Duran.

“He hasn’t been as awesome as a welterweight because these fellas he’s fighting now take a better punch than lightweights,” Freddy Brown concedes. “He’s going up to bigger men. It’s like a light-heavyweight, say Bob Foster, when he fought Frazier and them other guys. His punches didn’t mean nothing. With the light-heavies he was a killer. But when he went into the heavyweights they took his punches like he was nothing. And he got knocked out.”

That can’t happen here, the trainer says. “Moving up hasn’t cost Duran his punching power. When he hits ya, he hurts ya. I don’t care who it is. Take Palomino. Who ever knocks him down? He knocks Palomino down. He’s like a Marciano.” Ah, Marciano. Brown worked with Rocky Marciano in all his title fights. “He’d go along and hit ya, and nothing would happen and all of a sudden he’d hit ya that good one and that was it. Duran’s the same way. To me, Marciano was one of the best one-punch fighters we ever had. Duran’s got that same thing.”

Duran, who turns 29 the week he begins punching at Leonard, June 20 in Montreal, is beginning his 14th year as a professional, a long time to keep the pilot light operating behind those glowing eyes. When he began ballooning to 170 pounds between title defenses, the shift to the welterweight class was inevitable. As champion, he trained hard to lop off the weight; not so hard the last few years.

He explained his failure to score a knockout against Carlos Palomino by saying the weather in New York bothered him. But that fight was held in late June. So, was Duran saying the weather was unseasonably cold? It doesn’t seem likely. And if he meant it was too hot, what’s the point of growing up in sweltering Panama City? (Translation: He didn’t train.)

Last September he went 10 rounds, and was cut, against a stranger named Zeferino Gonzalez. Duran says he was sick for three weeks before the fight and Brown wanted him to pull out and the only reason he fought was that he had already spent the three weeks in Las Vegas. Huh? (Translation: See above.)

“When he was on top as a lightweight, he didn’t know who he was fighting,” Arcel says. “He didn’t know their names, didn’t know anything about them. He didn’t care. And it didn’t matter. Our job is to get him where he was when he beat Buchanan. If he gets that way, mentally, and he’s in shape…”

When Duran began his training in New York—“We’re getting him in the cycle, we’re moving him around, we’re shaking his ass a little,” Arcel says—he was at 159 pounds. Not bad for step one. Mentally? Well, the day he had the close call with the clean socks, he told Henriquez he had a cold and a slight fever. But he went to the gym and beat off the usual crowd. One of his sparring partners was Kevin Rooney, a young pro with four fights. For two rounds, Rooney stayed with Duran, trading, catching, coming back. At the end of two, Brown sent Rooney away and called for another sparring partner. Mentally, this was for Duran’s benefit. Rooney, for his part, was asking for more. Later, when Rooney was punching the speed bag, he talked about Duran. “He’s great,” Rooney said. “And when he gets in shape…”

This was another of those afternoons that proved Duran couldn’t train at Gleason’s and jump rope at the same time.

With the fight still two months away, the Duran camp seems determined to show some early jitters. Arcel explodes when he discovers that three Yankees—Reggie Jackson, Luis Tiant, Ed Figueroa—will be visiting the gym for the urgent business of publicity photos. “I been in thousands of fight camps,” Arcel fumes, loud enough to be heard at Pompton Lakes, “and I handled thousands of fighters. But I never heard of anything like this. Who cares if the ballplayers are supposed to be here? We don’t need them. Screw the ballplayers.”

Then it’s Duran’s turn. After he is told that today he is to buy a suit for the press conference later in the week, Duran remembers he has a cold; that his one-dollar admirers are getting on his nerves and his toes. Maybe it bothers him that young Kevin Rooney didn’t understand he was in with manos de piedra, the hands of stone. Who knows? Could be, he doesn’t like to buy suits. In any case, he isn’t going shopping.

Two hours later, to prove how seriously all this should be taken, Duran is back in his hotel room, smiling, admiring a beige suit. (“We call it copper or light rust,” the salesman says. Henriquez had persuaded the salesman to come to the hotel for this one-suit shopping spree. Along with a tailor. And four other suits for Duran’s appraisal.) Duran decided on the beige silk number in approximately the same time he needed to dispatch Benny Huertas. “How much?” I asked. “Four seventy-five,” the salesman answers. “A special price?” The salesman gives me a strange look.

The press conference decided the winner of the fight. We have Ray Arcel’s word on that. After the interviews—Leonard talks mostly about money, Duran only about winning—the Panamanian and his trainer become separated. They meet again in the corridor. Arcel embraces his fighter, keeping his hands tight on Duran’s shoulder, wrinkling the silk, and puts his hawk nose close to Duran’s face. “You won the title right there,” Arcel says firmly. “The other guy was full of crap. He’s scared. As soon as he goes back to his room he’s going to go in the bathroom.”

Duran nods, laughing. He runs off a couple of sentences in Spanish and Henriquez, standing at his side, holds out both his palms. Much joyous slapping. “What he said,” Henriquez says, struggling with his laughter, “he says, where he comes from, in the ghetto, they got a saying: those that blink, blow. Leonard, he was blinking.”

The good mood continues through lunch. “We all invited,” Henriquez says, explaining the pig’s head, with stuffed olives for eyes, sitting at the center of Duran’s table. A sign identifies the monstrosity as “Sugar Ray Lener.” Mentally, Duran is having a splendid time. “Steak,” he tells the waiter. “Well done, bien, bien.” Arcel whispers, “He loves steak. This is a kid who had to steal to live, who fought to eat. Now, he can’t eat enough.”

Does Duran remember his first steak? He smiles and tells the story to Henriquez, who plays it back. “He was an amateur and his manager took him to eat in a restaurant. First time in a real restaurant. The manager wanted a drink and Roberto, he told him to walk over and get it. It was a big restaurant, see, and the manager needed to take a long walk. He tricked the manager. Instead of eating one steak, he ordered two. By the time the manager got back to the table, the steaks were gone. They didn’t last three minutes.”

When this steak arrives, Freddy Brown intercepts Duran’s plate and dumps the french fries. Duran takes the usual three minutes. The waiter is offering dessert. “No dessert,” Brown says. Duran mimes a shrug, points to the pig. The welterweight champion will pay for this prison diet.

Duran wants his translator to make sure I understand one thing: “This fight, this chance to win a second title, is the greatest thing to happen to me. I was dying to fight Leonard. Or Benitez. Or Cuevas. Any welterweight champ. I can’t believe I’m getting this chance so quick. I’m so happy…. I just can’t express that happiness in words. Maybe if you ask me…”

But there is nothing left to ask. Nothing he hadn’t covered in that last intense speech. Instead, he’s offered dessert. Mentally. “Tell me about the one knockout that’s not on your record. The horse.”

Duran smiles. “There was a fair in his neighborhood,” Henriquez translates, “and he was in love with a fine girl but he didn’t have any money. They promised him that if he knocked the horse down they would give him two bottles of whiskey and $10.”

“Did he knock the horse down with one punch?”

“Si. One punch.”

“How old was he?”

“Fifteen years old.”

“How old was the horse?”

“He say, ask the horse.”

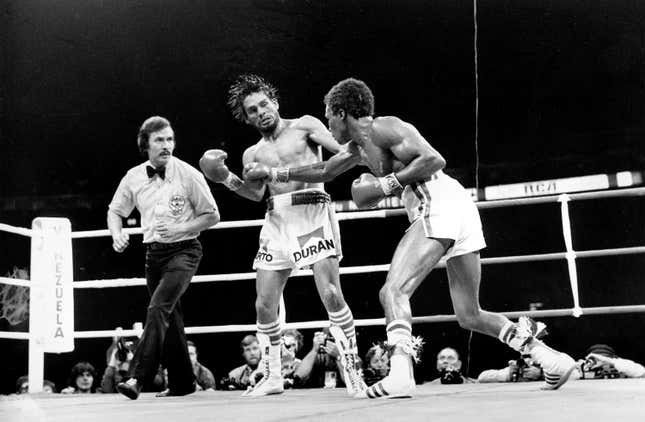

Duran won his fight against Leonard in a 15-round decision. During a rematch months later, Duran surrendered in the eighth round.

The Stacks is Deadspin’s living archive of great journalism, curated by Bronx Banter’s Alex Belth, who also runs Esquire Classic. Follow us on Twitter,@DeadspinStacks, or email us at [email protected].