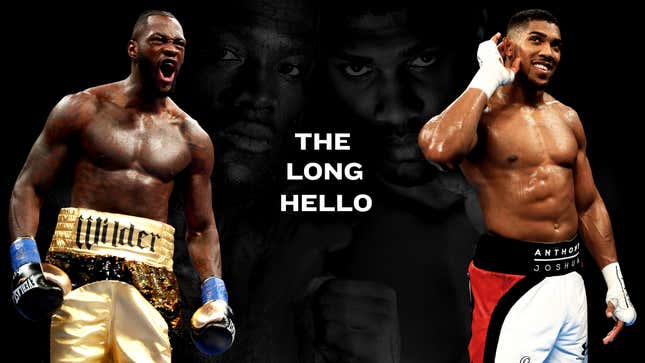

On Saturday, March 3, at Barclays Center in Brooklyn, New York, Deontay Wilder, one of the worst heavyweight champions in boxing history, will successfully defend his WBC title by first-, second-, or third-round knockout of Cuba’s Luis Ortiz, the best and most dangerous heavyweight fighter today. The win will set up a title unification bout later this year against WBA Super World and IBF title holder, England’s Anthony Joshua, who will hold up his part of the deal by taking the WBO belt from its current title holder Joseph Parker at the end of this month.

Wilder’s reward for his win will be the right to be ritually sacrificed in front of nearly 100,000 screaming zealots in the highest-grossing heavyweight title fight ever. He will earn upward of 20 million dollars for his involvement, which should take up under 10 minutes of his time, one-minute rest breaks included.

The end of something is better than its beginning. Patience is better than pride.

(Ecclesiastes 7:8)

But Let’s Back Up a Little Bit: The Fight That Didn’t Happen

Sometime last summer, Deontay Wilder and Luis Ortiz signed for a fight scheduled for November. For anyone who understands the business of boxing, it was evident that the fight would not take place, and that everyone involved, other than Wilder himself, knew it.

Ortiz was, and still is, the ultimate all-risk/no-reward heavyweight opponent. You will earn almost no money fighting him, and in a real fight he is nearly certain to knock you out. In Wilder’s case, you can omit the “nearly.”

So why sign a contract? What would be the point of signing for a fight that, unless fixed, would guarantee that the 32-year-old Wilder would lose out on the chance to finally recoup all of the losses that Al Haymon has incurred with him by misjudging both his marketability and his boxing skills? More significantly, why sign for a fight you have no intention of allowing to take place?

There are a couple of reasons worth exploring. First, there were serious issues in how Wilder was being perceived by the boxing public. Even his most enthusiastic supporters were growing uncomfortable with the quality of the champ’s opposition: things just looked fishy there. If your guy can fight, surely you don’t need to dredge the swamp every time in order to find an opponent he can beat. Why didn’t Wilder’s people have any confidence in him?

Maybe because of the increasingly unsettling reality that Wilder wasn’t running roughshod over the hand-picked third-raters being brought in to make him look like a monster. He was actually struggling—frequently visibly rocked by shots unlikely to have gotten a good heavyweight’s attention, thrown by opponents whose inclusion in the ratings were nothing more than a business accommodation.

Worse: Despite a substantial number of professional fights under his belt, Wilder seemed to be making no progress, continuing to become flustered whenever troubled, often reduced to desperate beginner’s off-balance flailing.

Finally, there were two conspicuous first-round knockouts that, in light of the nature of Wilder’s other wins, seemed oddly incongruous. The Malik Scott kayo was so blatantly staged that Wilder’s defenders still get blank looks on their faces when questioned about it. There’s no way it can be comfortably placed in any Deontay Wilder Feel-Good Story.

Then there’s all the stuff with Bermane Stiverne.

Easier the Second Time Around: The Bermane Stiverne Episodes

Deontay Wilder has had to go to a decision only once in his pro career. He captured the WBC title from Bermane Stiverne in a January 2015 fight where the champion did nothing for 12 rounds, throwing only 327 punches, landing an average of just over nine per round.

[Correction: This article originally claimed that Ronnie Shields was in Stiverne’s corner for the fight. While Shields earlier trained Stiverne, he was not his trainer for the Wilder fight.]

Don King had two crucial tasks in front of him regarding Stiverne, a virtually unmarketable 36-year-old heavyweight champion whose title was doing him no real good, and the WBC belt. To his way of thinking, the more important of the two was to get his foot back in the door for promoting heavyweight title boxing, where Eddie Hearn had overtaken him, and Al Haymon was about to. The other one was to get Bermane Stiverne paid without wrecking his chances for future opportunities.

King was willing to sacrifice Stiverne in exchange for some money and a bargaining chip. It was a sacrifice that suited Stiverne. He was only going to keep his title for one or two defenses at most, and he’d be making peanuts for those. Even his official payday for the first Wilder fight was only about two-thirds of the million dollars the challenger got. You don’t hand over the championship belt of your fighter to another promoter’s fighter for the short end of the stick.

King, a genius at calculating the value of everything boxing-related, parlayed his arrangement with Haymon into four distinct paydays, three of which benefited Stiverne.

In exchange for his lethargy and personal sacrifice, Bermane Stiverne would be presented with a gratuity. What that gratuity actually was, probably only two people can say. Even though Stiverne wouldn’t have been one of them, but he would have been the recipient of a large part of the gratuity nonetheless.

For reasons that might have been hard to fathom at the time but turned out to make a lot of sense, Bermane didn’t go careening around the ring in the first round of the first fight. His refusal to take a knockout loss kept him alive as a TBA entity, ready to be rolled out whenever, in order to do whatever. That came in handy when Luis Ortiz suddenly got popped for a drug violation, caught with two masking agents in his urine. Now would be the time for Stiverne to go careening around the ring in the first round.

King’s providing Bermane Stiverne as a vehicle for Deontay Wilder’s trip to the heavyweight title gave the promoter an opportunity to partner with Al Haymon in the staging of the new champ’s first defense five months later against Don King Promotions fighter Eric Molina, an opponent who may have come honestly by his top-20 rating, but about whom little more can be said.

Molina was an earnest but terribly limited fighter, and Wilder managed to win a genuine knockout in a competitive bout. It’s unlikely that King believed Molina would win, and he was probably just as happy that he didn’t, because Stiverne was still in the bullpen. Had Molina won the title, he would have been a less marketable version of Stiverne. Similarly, he would have to be bartered off; at that point King would have found boxing’s major power players even less willing to work with him than they already were.

The Dissenting Voices of my Colleagues

After I wound up on Twitter a few years ago, the site unexpectedly introduced me to a knowledgeable boxing crowd, including an abundance of first-rate boxing writers with whom I now often bicker in a pleasantly fraternal way.

When Luis Ortiz initially signed to fight Deontay Wilder in the summer of 2017, I perhaps too pedantically opined that the fight would never take place: Luis Ortiz was an infinitely better fighter than Deontay Wilder, and couldn’t be beaten by him in any real fight. I wrote—again perhaps too pedantically—that there may be arguments for making a heavyweight title defense in a fight you have no chance of winning, but none of them include losing for no money as you allow yourself to be humiliated.

A surprising number of people jumped in to voice their emotionally charged disagreements. I found my position contradicted by those who insisted that Deontay Wilder had “devastating power” and “blinding speed.” His “athleticism” would be way too much for Luis Ortiz, whose detractors dismissed him as “too slow” and “an old man.” Many saw Ortiz as a plodder who would be unable to corner his prey, and who’d be a sitting duck for Wilder’s long jabs and unpredictable follow-ups. Some talked about Wilder’s “wingspan” without bothering to make the due diligence visit to Boxrec.com, where they would have learned that Ortiz’s arm length is longer than the champ’s. I was even invited to compare Wilder’s one-round kayo of Malik Scott—the knockout virtually everyone concedes was a fix— to Ortiz’s later wide decision win over him.

Wilder’s supporters, all devotees of boxing as a sport, failed to take Boxing Business 101 into account: never risk giving something away for free when you’ve got enormous plans that would be scuttled by your loss. The fact that it has happened before (notably by Tommy Morrison, who lost a guaranteed multimillion-dollar unification fight with Lennox Lewis after being blown out in a round by no-hoper Michael Bentt, and by Juan Manuel Marquez, who, in the midst of hardball negotiations for a Manny Pacquiao rematch, made a chickenfeed stop-off in Indonesia, where his title was heisted by little known Chris John) only emphasizes the necessity of the rule.

The Dud on Top of One of the Hills

Al Haymon and PBC seem to understand that they have a problem with Deontay Wilder. They see how, despite the ceaseless “American heavyweight champion” rah rah, the nationalist glory of an Olympic medal, the lossless record, the cartoonish one-punch knockouts, the high-octane interviews that veer from piousness to over-the-edge violence—these things all bundled in with the genuinely heartwarming back story of the champ’s love for his daughter Naieya, whose spina bifida served as the catalyst for his embarking on a pro career—their guy just isn’t selling tickets.

Forget the major venues in Vegas or New York; Wilder can’t put asses in the seats of Birmingham’s small Legacy Arena in his home state of Alabama. PBC has been losing money on Wilder for years now. He’s a dud. With their business in desperate trouble on all fronts, PBC can’t afford to keep carrying him.

Wilder’s career has been a failed lab experiment featuring someone who can’t fight. Ultimately the only way his inventors will be able to recoup the millions spent constructing him and keeping him alive is to sell off his belts to Anthony Joshua for the $20 million or so they can pry out of Eddie Hearn.

Why would a fighter who is in line for the biggest payday of his life—by an order of magnitude—and who has to this point been sedulously steered away from all by the most harmless of opponents suddenly veer off course and take on the most skilled and dangerous fighter in the division?

He would do it if He knew beforehand that he was going to win.

Better Make Sure Your Friends Are Your Friends

Boxing history is replete with double-crosses, so it is often advisable to take one small step before making a giant leap.

In order to do business with Bermane Stiverne or Luis Ortiz, you would first have to trust that they’d do what they agreed to do.

Obviously, Stiverne has come through. He did nothing to cause Wilder any alarm in their first fight, and was all lined up in every possible respect for the rematch. His part in the equation is now over, and he’ll never be heard from again. One hopes that his compensation was sufficient for the fine work he turned in.

With Ortiz, it’s so far, so good. He allowed Wilder to talk tough the first time out, assisted the champ in being able to credibly boast about being willing to accept the toughest available challenger—someone no one else with a belt or a brain would be caught dead fighting—and then got himself removed from the scene through a drug violation that could be overturned quickly without a lot of noise, bringing him back into the Big Picture just in time to jumpstart Wilder’s bona fides in advance of the massive Joshua-Wilder buildup.

This lengthy process from Stiverne 1 to the Ortiz no-go to Stiverne 2 to the Ortiz go may have been lacking in nuance—a heavy-handed progression that’s easy to read if you’ve studied the boxing business—but it has been well thought-out and flawlessly executed to this point, and is nearing its successful conclusion, even if the buildup to the real payoff is only just beginning.

Easier the Second Time Around Again: Goodbye, King Kong; Hello Luis Ortiz

I frequently receive messages from people asking, “Why would anyone throw away the heavyweight title? They worked so hard to get it.”

Let’s look at that. For starters, with boxing titles being splintered by various organizations’ belts, there seldom is a real champion per se anymore. The only intrinsic value in being a “champion” is that you can ransom off your belt to a better champion who has a market interest in unification. If being an ersatz heavyweight champion brings you under a million dollars for each title defense, it’s smarter to earn the $3 to 15 million you’ll be paid for losing the title. Jack Dempsey summed it up best. “There’s only one reason fighters fight: for money.”

And heavyweights—putatively, still the toughest fighters in the world—are the only guys who can potentially make retirement fund-level paydays without having to win or without being particularly good. So there is real incentive for older heavyweights to look for insurance policies that allow them to cash out and get on with their lives.

The penny has finally dropped for Luis Ortiz. He has figured out that at 45 or so, his time for making money in the heavyweight division or for getting the title shots that he deserves and would win would no longer exist, if it ever did.

Ortiz had tried a number of approaches to entice the upper-end money fighters to take him on. He’d presented himself as King Kong, pounding his middle-aged guy’s slightly sunken chest, and then effortlessly destroying some of the fighters who had been at least slightly problematic for other top heavyweights. He briefly signed with Eddie Hearn’s Matchroom Sport—a deal-with-the-devil arrangement that would have kept him active, visible, and well paid in exchange for acting as a paladin for, while never challenging, the promotion’s mother lode, Anthony Joshua. He reversed gears from his earlier tactic of terrorizing the division by letting himself look less than formidable, carrying inferior opponents in the hope that others would decide he wasn’t such a bad motherfucker after all. Nothing worked. In the end he has become another foot soldier. We’re going to see him go out on his shield for the greater good.

Bullshit aside, he’s doing this for himself. Having reached the end of his options, he may be making the smartest available choice. In boxing, if you can’t make money one way, sometimes you have to make it another.

The Conversation Stopper

The first time I saw Deontay Wilder, fighting Damon Reed—who seemed to be actively inviting his opponent to knock him out —in June 2011, I felt certain within every fiber of my being that I was watching a fraud. Time hasn’t softened my initial impression. Deontay Wilder can’t fight at all. That’s a harsh judgment, and one that bothers a lot of people, including many who make money in the boxing business.

The rebuttals to my all-in rejection of Wilder—at least the ones that are presented to me in words rather than little cartoon pictures—tend to focus on his putative athleticism and speed, on what a nice guy and fun interview he is, and most significantly on his power.

My response to anyone trying to sell me on Wilder’s power is to ask about Wilder’s first-round knockout of Malik Scott. It’s a yes or no question. Did Malik Scott take a dive?

Wilder’s staunchest defenders grow silent at this point. Everyone else, some with reluctance, owns up to its being a fix. No one with whom I’ve spoken believes that Deontay Wilder actually knocked out Malik Scott.

The fact that Deontay Wilder can’t fight is unimportant in the Big Picture as long as enough people think he can—and some who didn’t think so will change their minds after the Ortiz fight— so that he comes into his fight with Anthony Joshua as a credible B-side. Ideally, he should be credible enough so that, in the Buster Douglas-ish event he actually won, it would make even Hearn’s people pleased with the result. Deontay Wilder will be able to manage that degree of credibility. Most people will never know what it took for him to get it.

The Traveler Blocking the Path and Why Everyone is Happy to See Him

While the Anthony Joshua vs. Deontay Wilder title unification will monetarily be the biggest event in heavyweight history, paying both participants with more money than any of the division’s champions have made in a single fight, for Joshua it will be only a warm-up to the real payday. Tyson Fury, the loose cannon lineal heavyweight champ—many say the true champion—has made it clear that he is back from his peregrinations, consisting of two years spent mostly binge eating, partying, and ricocheting from mania to depression like an penny arcade pinball game on tilt.

Fury’s claim of being the actual champion is valid. He offhandedly beat the same Wladimir Klitschko who had Anthony Joshua no more than a few seconds away from being knocked out. Fury can point to the two fights as Exhibits A and B in establishing a case for himself as being the superior champion. That his win over an entirely unresponsive Klitschko marked a low point in heavyweight title fights while Joshua’s produced the best heavyweight contest in recent memory is beside the point. Joshua had to go through Hell to defend the title; Fury could have been singing his high pitched, out-of-tune croon to the ringside crowd as he was slapping away at Wladimir Klitschko while taking his belt.

Fury, owing to the currency of his outspokenness, and because he won his title in the ring and never lost it, is the only one who may currently be considered Joshua’s near equal as a public figure, although his eventual ceiling is much lower because he’d have to beat Joshua in order to persevere as a cultural icon. He’s not going to be able to do that. Eddie Hearn will still wind up having to pay him his asking price to allow him to try. Simply put, Anthony Joshua must face Tyson Fury.

Until Joshua disposes of Fury, there will not only always be “What If” questions floating around, there will also be corporeal truth of the 6-foot-9, 300-pound, disruptive Traveler himself, placing his sun-blocking lumpy carcass directly in the path of every available video camera and microphone, agitating, haranguing, joking about, mimicking, and challenging the man whose most notable win was over the guy Fury had already beaten more easily when taking his title. Fury may not be much of a fighter—there are a lot of differences of opinion on that—but he is one hell of an entertainer once removed from the ring, and he threatens to upstage anyone else, including Joshua, until someone manages to conclusively shut him down in a prizefight.

The Long Hello

Anthony Joshua is facing a predicament, if it can be said that anyone likely to earn between $60 and 80 million for taking on two pushovers in approximately 10 minutes of work can be said to have a predicament.

After dispatching Joseph Parker in March, his next opponents will be Deontay Wilder and Tyson Fury, probably—and preferably—in that order. The Wilder fight will break all box office records for heavyweight fights, immediately after which the Fury fight will break those records. The problem then is that at that point there will no longer be anyone seen as having a chance of beating Joshua.

In the alternate universe of what could have happened but will never happen, the only fighter who would have a 50/50 chance of beating—and possibly knocking out—Anthony Joshua will be the thoroughly devalued Luis Ortiz, who will be conveniently and conclusively dispatched by Deontay Wilder on March 3. Ortiz’s defeat will exempt Joshua from the risk of taking on the Cuban, a bit of lagniappe that certainly will not have been lost on—and may have been in part orchestrated by—Eddie Hearn.

Anthony Joshua’s career has been engineered to put him on top of the boxing world, which means putting him economically on top of the sporting world. Ambitious as this itinerary is, it pales next to what I think is the ultimate plan for him: to make him the most financially successful fighter in ring history, which translates to becoming the most financially successful athlete in history.

He’s already got things nearly locked up in the U.K., with only Tyson Fury blocking his path to domestic hegemony. The recent tidal shift in boxing’s power structure combined with a revival of homegrown interest within U.K. boxing culture have given Eddie Hearn and Frank Warren opportunities to make enormously successful matches without leaving their shores. As well as they’re doing, there are signs that they may want more, and the timing for getting it might be about right.

The tail is about to start wagging the dog, with high-profile matchups within the U.K. drawing sizable viewing audiences from the U.S. Last month, WBA Super Middleweight Champion (technically the super WBA Super Middleweight Champion, but how stupid can we afford to be?) George Groves beat Chris Eubank Jr. in a fight that drew more interest than any recent heavyweight title fight staged in the U.S.

People not only know the records, opponents, and styles of these fighters, they know their back stories too. They follow what’s happening behind the scenes. The press conferences and weigh-ins matter. They care about the fighters. In large part, this is a matter of regionality: the Brits feel kinship to those fighters who come from their cities and towns. Regional identification, once a major factor in the building of fighters in the States, has diminished appreciably in recent decades.

The emotional investment of fans toward fighters is the most important element needed in order for boxing to again become a relevant sport. It’s something that’s happening in many parts of the world, with the U.K. surging; if the impetus can somehow carry over to the United States, a country steeped in the magnification of scale, enormous results can occur.

The Redcoats are Coming (and they’ve learned to not stand in a straight line)

America’s Choice of a Hero

Very few fighters go from being stars in boxing to becoming mainstream celebrities—public figures whose faces are immediately recognizable to people on the street. Floyd Mayweather made that crossover. He earned more money from boxing than anyone else, but never received the outpouring of heartfelt adulation that Manny Pacquiao received from his countrymen in the Philippines or Saul Alvarez gets from Mexican fans. Seldom has the disparity in investment of the heart more in evidence than when Floyd Mayweather fought Manchester’s Ricky Hatton in 2007.

It was with great hope and trepidation that Ricky Hatton was sent forth to The Promised Land of Las Vegas, Nevada; specifically to the Grand Garden. The weight of concentrated longing from an entire nation was draped over his not too broad shoulders, and many thousands of the Faithful accompanied him on his journey.

Maybe he’d be The One. If he could beat Mayweather, the peerless American—who, if you looked at it closely, had not accomplished so much more in the ring than their Ricky—the sometimes whispered, sometimes keened prayers of his countrymen would be answered.

The British form these types of unbridled emotional bonds with their fighters. But there’s also a long ingrained sense that their boys might not be quite as good as their American counterparts, so until recently the final imprimatur—their elevation from hero to legend—could only be obtained by flying a hero across the Atlantic, preferably to McCarran Airport in Las Vegas in order to beat an elite U.S. fighter at one of the major casinos.

One of the key events in Floyd Mayweather’s transformation from elite U.S. fighter to international superstar was the direct result of Hatton’s failure to beat him. In the end, although he fought aggressively and bravely, Hatton was out-thought, lured onto new and unstable ground, and put away by a tricky Black Code punch that he didn’t see coming. The mystery of that punch—its incalculability to both Hatton and his fans— described a chasm of difference. Hatton wasn’t The One after all. The one who beat The Would-Be One must be The One.

The Hatton knockout was the second and final step in Floyd Mayweather’s ascension from being the B-side of a megafight to the A. He had been the B-side in his fight with Oscar De La Hoya seven months earlier.

Mayweather had fought poorly in that De La Hoya fight—seemingly deliberately so— in winning a split decision that was only split thanks to Tom Kaczmarek’s cooperative pro-big business judging, thus leaving the door open for a lucrative rematch that never wound up taking place and that ultimately Floyd would never need.

Parenthetically, Hatton was given another chance at the Grand Garden a year and a half later, but the feeling among his faithful as to his chances wasn’t the same. On this—his final visit—he was quickly and emphatically sent to Dreamland by bona fide superstar Manny Pacquiao—Dreamland being the place where Ricky and his millions of fans were forced to concede they’d been living for the past 18 months.

The eventual bursting of most U.K. fighters’ bubbles at the fists of their American counterparts created about their fans a kind of embarrassed cringing that stood beside whatever hopes they held out. At least this was the case until recently, when a plethora of champions began to emerge from a number of U.K. countries. Carl Frampton, George Groves, James DeGale, Kell Brook, Billy Joe Saunders, Terry Flanagan, Anthony Crolla, Ricky Burns, Lee Selby have all been recent world title holders. Yorkshire’s Josh Warrington will be taking on Welshman Selby in May in a fight for pride that will do tremendous business in Leeds. Josh Taylor is on the verge of becoming one of boxing’s hottest properties. These are all excellent fighters, many good enough to make names for themselves across the Atlantic.

But Anthony Joshua changes the boxing terrain entirely. No longer is there any need for a qualitative asterisk to be placed beside the name of a world heavyweight champion from the UK. Even arguments about the provenance of genuine title ownership can be legitimately confined to Joshua and Fury, both British-born fighters. For once, not only does England have The One, they have him in the heavyweight division, where it has always mattered most.

Joshua can be the catalyst for boxing’s transition to the billion-dollar era. He could probably get halfway there without ever leaving England, but ultimately that wouldn’t be the smartest move for him, and it certainly wouldn’t be the best thing for boxing. Boxing, with the implementation of some astute business decisions, a number of memorable fights, and a cultural adjustment that takes internationalism into account, is on the verge of a major transition. It requires American fight fans to see fighters first, nation of origin second (or to not see it at all). It requires U.K. fans to inculcate a firm understanding that their guys might not just be better than their other guys, but sometimes better than anyone, anywhere.

When Anthony Joshua knocks out Deontay Wilder somewhere around the end of 2018, the American will be a minor player in the drama. Wilder will make a ton of money, and he’ll have his adherents, but everything about this event is geared to a turning on its head the notion of who comes first. The ultimate goal is for Anthony Joshua’s smiling face to be as omnipresent in U.S. advertising and on TV late night talk shows as it currently is in Great Britain’s. The pay scale for his services ought to increase by 1000 percent from this transition. He just needs to make sure not to abandon his U.K. fan base. He can come to America, he can make his biggest money in America, but he can’t ever afford to “go American.”

Selling the Product or Merely Delusional?

Below are some recent statements from Deontay Wilder. He manages to combine ignorance and arrogance in a way that closely mirrors the style he has in the ring. It’s a toxic gumbo of technological misconceptions as they pertain to boxing, stunning lack of self-awareness, and cultural disrespect for his forbears. If what he said—idiotic as it is—could help him at the box office, I’d be all for it. Mike Tyson’s saying he’d eat Lennox Lewis’s children probably did both guys a world of good.

“Me vs Tyson in ‘86, I’d kick the hell outta that guy,” said Wilder. “Listen, I’ve got to keep it real, I know people always go back to the Old School or look at the New School and there’s no school where I’m not No. 1 on earth.”

“My hand speed, I’m too long, I’m too tall, my athleticism, my foot work, all that gives me an advantage, it plays a big part.”

“No disrespect to Mike Tyson, in his era he was the best but this is a new era. No Old School fighter should beat a New School fighter. Look at the technology we have.”

“Nobody has a natural killer instinct as I do, ain’t anybody could ever knock me out. I’m very confident in what I say and I speak what I do.”

These are some bold assertions. Fucking demented ones, to anyone who knows shit about boxing.

Primo Carnera believed his fights were real too. Everyone around him assured him that they were.

Back In the Alternate Universe

Could They Really Be That Stupid?

Still, what if Deontay Wilder isn’t the only one in his organization who believes his foolishness? It seems inconceivable, especially taking into account the ultra-careful matchmaking and fixes staged on Wilder’s behalf. But not everyone involved in boxing these days, even at the upper echelons of the business, knows anything about the game. Could Team Wilder have developed a genuine but totally unfounded confidence in their fighter at the exact moment when it can least be afforded?

All the work. All the preparation. The caution. The side deals. Years of maneuvering and millions and millions of dollars spent. A Long Hello; a process visualized from a great distance, moving closer step by step. Could that all be the product of anything other than cynicism?

Something to think about. Wilder is a big favorite. Ortiz could make more money double-crossing everyone, betting his purse and whatever else he can lay his hands on on himself, and letting the chips fall where they may, than he will for cooperating. He’d also wind up holding the WBC heavyweight title, for whatever that’s worth. Back when wiseguys still controlled much of boxing, they’d have known what to do.

The bell rings at the two-thirds sold out Barclays Center and Deontay Wilder leaps out of his corner throwing blindingly fast jabs into thin air. Luis Ortiz, as his critics have noted, does look glacially slow as he inches forward. He watches Wilder quizzically. Wilder snarls and grimaces, adds wild hooks and overhand rights to his jabs. Not solidly planted, his feet leave the round with one of the hooks. Ortiz moves his head, shrugs his shoulders slightly, shuffles ahead. He’s looking for the perfect spot. Luis Ortiz has always been a patient man. He knows the shot will come.

Charles Farrell has spent most of his professional life moving between music and boxing (with a few detours along the way). He has managed five world champion boxers and has 30 CDs listed under his name. His essay “Why I Fixed Fights” is included in the boxing anthology The Bittersweet Science: Fifteen Writers in the Gym, in the Corner, and at Ringside, edited by Carlo Rotella and Michael Ezra, and published by the University of Chicago Press. He is featured in the 2016 film Dirty Games, directed by Benjamin Best.