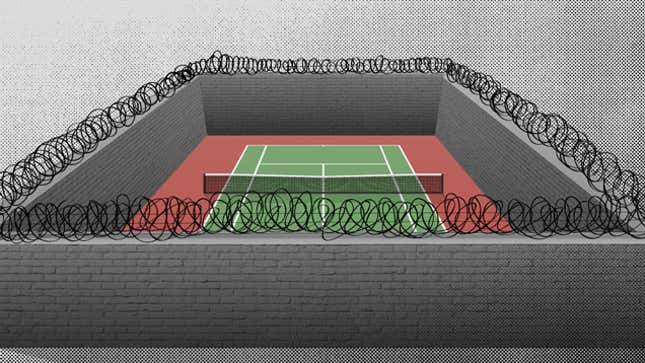

The next time I commit a felony, I think I'll do it in California. It turns out that San Quentin has a fabulous tennis program. The court I played on during my time in the New York State prison system was a total wreck. Two summers at Groveland Correctional Facility (starting in 2009) did improve my serve, but of all the sports to play in the clink, tennis is the one most heavily burdened with issues of class and race. Easier to play basketball or lift weights, believe me.

As far as I know, only that one prison in New York's system has a court, and it is barely even an actual tennis court. Thirty years ago, a progressive warden had the idea of classing up his joint by recycling an unused basketball court after fresh ones had been installed. Paint was applied to the terribly cracked asphalt that had seen a million dunks. The hoops were removed, and posts installed on either side of center court. A volleyball net was strung up between them, and four tennis rackets were bought on sale. Groveland now featured tennis for the inmates.

Whatever intention the long-gone warden had for the court has been forgotten, but the raggedy net and serving boxes survived long enough for me to use them. Playing tennis in prison seemed a luxury to me. I had not held a racket since taking a series of lessons at a public park in New Jersey in the early '90s. But I joined the scene whole-heartedly, playing in our little tournaments and picking up what I could from our star.

Star? Yes, Groveland CF had its own John McEnroe, and he was every bit as ornery. We'll call him Jim, and he was a frat boy gone bad. Bad enough to be on his third trip to prison, this time for a drunken motorcycle accident, previously for cocaine. He came of genteel stock and had played on the courts of the Rochester suburbs for his entire youth, eventually earning himself a scholarship to Colgate. But he also lived the fraternity lifestyle to the hilt—in fact, well beyond the hilt. I met him when he was about 40, and, god, could he play. There was no true game between us unless he kept an eye closed; he even beat me using only his left hand. The only way to get a competitive game with him was to play doubles and pair him with the worst partner—sometimes myself.

Jim and I were not the only enthusiasts. This particular prison was medium security, and it seemed to be one of the safest. As a result, many prisoners who might not have done so well in other places would land there, although I somehow managed to get transferred to Groveland straight from solitary. Jim the Bad Frat Boy may have been our star, but we also had a crooked investor and a violent doctor and a thieving lawyer (shocking, I know)—basically, a crew of guys with upper-middle-class backgrounds who didn't mind buying their own balls (which were rejected by the package room half the time for being "sealed improperly") and playing under the glaring sun on a cracked and worn surface. In truth, it was some of the best fun I had while incarcerated, playing there in the locked-down Wimbledon in my head, and sometimes just watching the grace of Jim's serve was enough.

But that was part of the problem. We weren't there to have fun and work on our backhands. We were there to be punished. In prison, anything the convicts enjoy eventually becomes an issue.

The other problem: Every single person who played tennis, from the pick-up games to our little tournaments, was white.

The graph at left illustrates that the incarcerated population of New York State does not match the racial ratio of the free population in the least, or at least it didn't in 2002, shortly before my own incarceration began. Less than 20 percent of NYS prisoners are white. The reasons for this require another article, or maybe a thousand of them, but in any event, every tennis player was white, and this did not sit well with the community of convicts of Groveland CF. And it didn't help that by coincidence or not, Groveland was reputed to be the whitest prison in the state.

Being savvy to the racial politics of prison, our little tennis scene reached out to the rest of the guys. The Latino handball players had a strong aptitude, and many of the black prisoners were superb athletes, trained and disciplined in sports like football, softball, and basketball. But our efforts did not amount to much. The "guests" we invited to our tournaments found other things to do, and the guys who did show some curiosity in learning the game played by Serena and Venus and Arthur Ashe were quickly discouraged by their friends. Because the word was out: Tennis was racist.

One day, we found that all of the balls in the recreation shack had been knocked as far away as possible, with only the fencing around the prison saving them. Another morning, we showed up to discover a racket that had been deliberately smashed. And then there was the constant smell of piss on the court, not to mention all the little brown starbursts of spat-up chewing tobacco covering the surface. The good ol' boys, it seems, weren't too fond of the game, either.

If this had been the extent of the problem, it could have been dealt with. But there was also the matter of the guards. These men spent more time with us than with their own families, and they knew each prisoner by name and habit. Their backgrounds were mostly local: sons of fathers who ran the local dairy farms and quarries and lumber yards and construction companies. While some were attracted to the job because of the opportunity for sanctioned sadism, most simply appreciated the hefty overtime and full benefits. At Groveland, the guards had little to do, since it was so safe, which meant that they had plenty of time to watch us play tennis from their tower.

And to hate it. Every interaction with the guards regarding the tennis court was an exercise in humiliation. When rackets broke and we needed new ones, when the old volleyball net ripped (accidentally?), when the lines needed a fresh coat of paint— every request was met with a sneer and delay. All around us, fresh basketball hoops were going up, and new gloves for the softball league were sprouting on the hands of the players, but getting a new racket took a month.

It wasn't hard to see what was going on. All the submerged class and racial anxiety surrounding tennis in the world beyond my prison walls lay exposed on the surface within them. Inside, where we spent so much time looking at one another, these visceral issues bubbled up in many ways, including through the sports that convicts chose to play. Jut as Foucault once wrote, prison is the most convenient microcosm for looking at a society.

The prisoners I knew were not as attuned to the dynamics of class as they were to those of race, but the guards were pretty clear on who was who. Everyone they watched playing tennis over a volleyball net on that cracked court had better educations than they did, had probably been to Europe, had probably slept with more refined women. As a result, our overlords were not looking to do the tennis scene any favors.

In one particularly unpleasant incident, we were reminded of the powers of violence that they held over us. During a game of doubles, we were arguing a point; this often happened, as the cracks in the asphalt made the balls bounce strangely, and the court boundaries were hazy. Jim was a loud one; I held my own; the crooked doctor mumbled his protests; and our nefarious accountant suddenly turned into a fire-breathing dragon. We had been in the sun for a while at this point.

In no time at all, a whole squad of correctional officers descended upon us. With my face squashed against a brick wall, I was told that "tennis-playing motherfuckers" like myself "need to be taught a lesson." Then the guy suggested that I take my hand off the wall—had I done so, he would've had carte blanche to beat me down with his club. Similar things were happening to the other three guys. Eventually, a sergeant came and defused the situation. Once things were calm enough for me to speak up, I questioned the reason for any of it. Turns out the guards in the tower had called in a "gang assault" that we were obviously initiating on the tennis court. Not one person in that tense room really believed a word of this, but it was a message from the the cops: They did not think that incarcerated criminals should be playing tennis right under their tower.

The cops may not have liked tennis—and most of the other prisoners agreed—but we sure did. We did not let the incident with our "gang assault" hold us back, as prisoners often acquire a perverse pride in tiny gestures of defiance. Jim the Bad Frat Boy was the face of the scene, and luckily he was brave and pugnacious enough to defend the sport against the accusations of racism. He would bring up Venus and Serena, marvel at the basketball players' dunking, and invite them to try and learn the game. Still, the tinge of elitism and racism never quite went away, and the tennis players were held at arm's length by the more radical and resentful prisoners. The guards never did reconcile themselves to it. They hoped for rain every day, gleefully sending us all inside at the first sign of a drizzle. It was to protect us from lightning strikes, they said, but somehow the guys playing softball did not require as much protection.

Things aren't so fraught in San Quentin, where, I recently learned, there are beautiful courts and real tennis pros coming in to play the guys who've practiced for 20 years while doing their time for murder. In the California penal system, it seems that the game is more tolerated and less burdened with America's bloody history of racism and class division.

In truth, tennis has a lot to say to all classes of incarcerated people, if only they'd let it. It's a sport about self-control, about succeeding within prescribed limits, about the lively variations that can grow out of narrow routine. And the outfits are much more flattering. Tennis may seem aspirational for some, but it could be inspirational for many. Trying to return the doctor's tricky serve, I could forget for a moment that I was locked up. No wonder the prisons tend to hate tennis.

Daniel Genis was incarcerated in 2003, and released in February of 2014. He's the author of the novel Narcotica and many translations from the Russian. Previously, he wrote about prison weightlifting for Deadspin.

Image by Jim Cooke.