“All the stuff I’ve done in my career,” Don Ohlmeyer once told an ESPN interviewer, “and that’s what I’m going to be remembered for. It serves me right.”

Ohlmeyer was referring to his decision, nearly 40 years ago, to air a nationally televised NFL game without any announcers. But after he died on Sunday at the age of 72, not one of the major obituaries about Ohlmeyer mentioned the announcerless game. In the end, he was remembered for many of the fingerprints he left behind as a television executive—Monday Night Football, NBC’s 1990s primetime lineup, Jay Leno, his bizarre loyalty to O.J. Simpson, his firing of Norm MacDonald, Dennis Miller on MNF, ESPN ombudsman—but when it came to his loud experiment with silence, there were no words.

The announcerless game was a ratings gambit. In those days, late in the season, after college football took a nap until the bowl games revved back up around New Year’s Day, there would be a national NFL doubleheader on Saturdays in December. CBS, which had the NFC rights, would air one game, while NBC, which carried the AFC, took the other. In 1980, the Jets were scheduled to play the Dolphins in Miami on Dec. 20, the Saturday of the season’s final weekend. But as it became obvious neither team was headed for the playoffs, it was likewise obvious the game would be meaningless.

Ohlmeyer was NBC’s executive producer of sports at the time. As he would tell Rich Eisen in a 2015 interview, NBC in 1980 was for the first time in a real NFL ratings battle with CBS—no small feat, considering the smaller markets that were concentrated in the AFC. Ohlmeyer was by all accounts ferociously competitive; he wanted to win this thing, and he was willing to try anything—even a game without any narration. More, from what he told Eisen:

“I’m sitting there thinking what could we possibly do to get people to tune in to this dog game? And I said, ‘I know, we’ll do a game without announcers because I always felt that announcers talked too much.’ And on the other hand, viewers always complain about announcers, and so here was an opportunity to send a subtle message to the viewer that you’re going to miss these guys if they are not there. Here’s a subtle way to send a message to the announcers that, you know, it could be done. ... See if you really matter or not, you talking head, you.”

At the time, as he and NBC worked to market the game, Ohlmeyer was adamant that his experiment wasn’t a dig at announcers. But it was difficult not to see it that way. And, naturally, the concept was not well-received by the network’s broadcasters. Dick Enberg, at that time NBC’s No. 1 play-by-play voice, was in a panic. “We all gathered together, hoping that Ohlmeyer was dead wrong,” Enberg told ESPN in 2010. “I mean, he was flirting with the rest of our lives. What if this crazy idea really worked?”

The Washington Post sent reporter Stan Isaacs to Miami to cover the game from a production angle. “A view of a man in the pits—I monitored the telecast from a press box set up in the stadium and visited the production truck and walked out to the sidelines—is that the telecast was exciting, provocative, sometimes boring, but a celebration of the technical side of television, and highly entertaining for the sheer novelty of it,” Isaacs wrote.

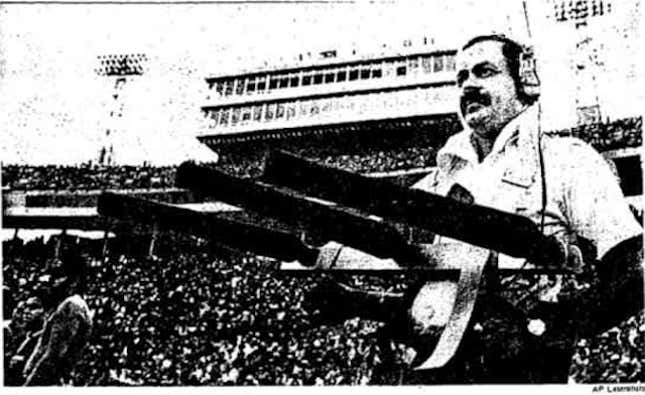

It was something less than entertaining from the viewer’s perspective. NBC tried to replace the announcers’ narration with several elements that have long since become common during football telecasts: additional graphics and stats packages, voiceovers by players and coaches, and the placement of sensitive microphones around the stadium that could pick up the sounds of the action. It was ahead of its time, even as the technology was still awfully primitive, as this Associated Press photo of a microphone technician working the game shows:

NBC tried to get the players mic’d up, but the league wouldn’t allow it. Additionally, the Orange Bowl’s PA announcer was asked to embellish his calls, and those calls could be heard throughout the telecast. And Bryant Gumbel, who did NBC’s pre-game show, occasionally interjected with updates.

All of these innovations required much more technical work than a typical telecast of that era. The graphics that flashed the down and distance sometimes appeared late, or not at all. The microphones sometimes picked up radio frequencies, or sounds that an associate producer later likened to a sizzling frying pan. The pre-packaged player and coach interviews sometimes ran long, or aired without context. Isaacs asked Arnie Reif, NBC’s director of sports technical operations, why the microphones didn’t capture the audio of a screaming coach, even when there was a visual. “We probably should have alerted our sideline audio man to that, but frequently there was too much else going on or the field mikes weren’t close enough to the coach,” was Reif’s answer. “At times we tried to do too much,” Ohlmeyer told Isaacs.

The game can be seen in its entirety on YouTube (at least until it inevitably gets taken down):

As I watched it, if my attention wandered for a bit, there were times when it was difficult to know exactly what was going on. Without announcers to fill in the gaps, it was a reminder that football is one giant stoppage punctuated with occasional action, rather than the other way around. Though, as Isaacs noted, there was some compelling pure visual drama, such as Duriel Harris’s second-quarter touchdown catch for Miami in the back of the end zone. For a few seconds, it wasn’t apparent Harris had scored until he got up and raised his arms:

The announcerless game earned a 13.5 rating, which was close to NBC’s regular-season average that year of 14.9. (The Jets won, 24-17.) Per ESPN, NBC’s switchboard fielded fewer than 1,400 calls about the game, with more than 60 percent voicing their support for the concept. “I can’t believe it’s anything more than a footnote,” Gumbel told ESPN in 2010.

At the time, the final verdict from critics was that the announcerless game put too much of a burden on the viewer. This was from David Israel’s day-after assessment in the Chicago Tribune:

As Marshall McLuhan long ago observed, television conditions us to respond passively, it does not challenge us to think, and here, out of the blue, it was asking us to participate actively, to provide input so that what was on the screen became something more than moving wallpaper. The masses of viewers who were unable to do that were left watching padded humanoids clanking heads.

In their interview two years ago, Ohlmeyer told Eisen he thought an announcerless game could be worth trying again, now that the graphics and the technical production is so much more advanced. His experiment flopped, and it hasn’t been attempted since. But what if the announcerless game was an idea that maybe just came along too soon? Something to remember Don Ohlmeyer for.