Of all the real-life characters in Friday Night Lights, Brian Chavez would surely have been voted Least Likely To Be Caught Brawling After Permian High Football Games Into Middle Age.

Late one fall Friday night in 2009, though—more than 20 years after Buzz Bissinger embedded with the Odessa Permian football team for a season—there was Chavez in handcuffs, sitting on a curb under police lights.

The aging schoolboy jock stuck in his hometown is a standard fictional character: Wooderson from Dazed & Confused, for example, or Al Bundy from Married With Children, or that unnamed speedballer from Springsteen’s “Glory Days.” But those guys didn’t have many options other than sticking around. The Chavez Bissinger portrayed in his acclaimed book, which inspired both the film and the cult TV show of the same name, had more options than a tricked-out Escalade.

He was the kid who used football instead of vice versa, acting like being #1 in his class meant as much to him as being #85 in the game program. Chavez was the strongest guy in the school, benching 345, and captain of the schoolboy football team in a region as obsessed with schoolboy football as any. He also got better grades than everybody else, went to Harvard, and gave up the game that made him famous. The book ends with Chavez just starting out in college, but as he made his way in life, he continued to validate Bissinger’s portrayal, graduating with honors and getting a law degree. A 2009 profile in the Odessa American gushed about how Chavez had “managed to juggle the jock and genius role.” Yankees loved him, too: In an extensive New York Times series on the book, writer Rachael Larimore tabbed Chavez as her favorite and most relatable character because he “embodied nuance.”

Chavez’s being the first player with Mexican roots ever named captain of the Permian football team—and Odessa now being a city with a majority-Hispanic population—gave him even more value as a role model.

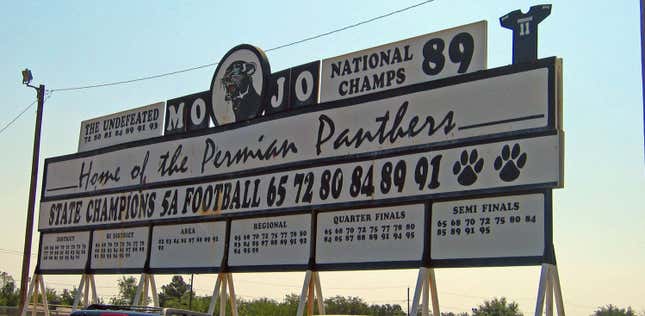

Odessa, Texas, 2004; photo via AP

But then Chavez was arrested after a violent home invasion on the east side of Odessa. The extensive police reports paint a bloody scene that mixed elements of House Party and Gettysburg. Police reports showed that Chavez spent the hours before his arrest attending a Permian football game at Ratliff Stadium, the local high school football shrine and epicenter of his teenage glories. Chavez’s mug shot, featuring him decked out in jailhouse attire, appeared in the local paper alongside the Permian game stories. Stanley Wilkins, a teammate from the 1988 team whose wildness was noted in Bissinger’s book, was named as a fellow invader.

Chavez was indicted and also sued by the victims, with the local media following every step of his downfall. The Odessa American put Chavez’s criminal case and related civil suits filed against him on a list of the Odessa’s biggest stories of 2009, alongside the reunion of FNL stars on the 20th anniversary of their graduation.

Chavez, who turned 40 years old as his future was being litigated, suddenly went from stereotype buster to lame cliché: The former football star, still going to his old high school’s games and still fucking up.

“This was the kind of thing you expect from high school kids, not full grown adults,” says Wes Mau, the out-of-town prosecutor brought in to throw the book at the local hero after some of Odessa’s top lawmen wouldn’t.

Adolescent or not, these actions had very serious consequences. Several tenants and guests of the home Chavez invaded were injured, and witnesses named him as the leading thrower of haymakers. He avoided jail time by pleading guilty to burglary with intent to commit assault, then settled the lawsuits through payments to the victims; the Texas State Bar Association then invalidated his law license.

“That was the darkest day of all,” Chavez tells me of the license revocation. “I took my license down off the wall and drove it to Austin to turn it in, hand delivered it, frame and all. Man, talk about feeling it.”

As the hits to his reputation just kept coming, the moral of Chavez’s saga seemed to be that you can’t judge the guy on the cover by the book.

Just in time for the 25th anniversary of Bissinger’s tome, though, Chavez is about to get a chance to prove that his heel turn was only temporary. Officials with the State Bar of Texas recently told him that he was fit for reinstatement. As of yesterday, his law license was in the mail from Austin on its way back to Odessa.

I asked Chavez about the imminent end of his court-imposed hiatus from lawyering.

“It’s like I got my arms chopped off,” he said, “and now I’m going to get my arms back. I’ll be able to fight again.”

The same folks who rooted him on as a kid are now cheering for his role modeling career to pick up where it left off. “Brian Chavez will fight and work hard to get back. I know he will,” says LaRue Moore, Chavez’s former English teacher and the academic Norma Rae of Bissinger’s book. “He’ll do whatever it takes.”

Given the way he undid his good name, his former English teacher would probably point out that both of them are using “fight” metaphorically.

“Brian walked in and hit Jaime in the mouth.”

Buzz Bissinger wrote in Friday Night Lights that Chavez told him he knew that he was “an asshole” whenever he was on the football field.

“But,” Bissinger wrote, “he figured it was better to be, as he saw it, an ‘asshole playing football rather than in real life.’”

On Oct. 2, 2009, according to the evidence, Chavez was an asshole in real life. By the end of that Friday night, he was under police lights, handcuffed and sitting on a curb. And the reputation he’d earned over a lifetime—the one trumpeted in movies and books and the New York Times—had taken a beating.

Lots of Chavez’s fellow Odessans took a beating that night, to go by the police reports.

As those accounts have it, Chavez’s troubles began when his girlfriend, Rosemary Soto, called her ex-husband, Jose Luis Jimenez, from Ratliff Stadium, where she and Chavez were watching a Permian football game. The exes began arguing about who would be taking care of their two children that night. Jimenez told police that when he took Soto’s call he was at a party where everybody was listening to the Permian game on the radio. He told police that the call ended when Soto announced she and Chavez were going to show up at the party, and that he heard Chavez in the background yelling that he was planning to “whip his ass.”

The game was enough to put any loyal Panthers fan in a fighting mood. This was the biggest sports night of the year in Odessa, in which Permian played Odessa High, the other secondary school in town. The annual series, which started in 1959, has long been regarded as Texas’s “biggest high school football rivalry” despite traditionally being one of the most lopsided serial matchups. (After getting shutout in the 1964 game by an Odessa Bronchos squad quarterbacked by future country & western cheeseball Larry Gatlin, Permian went 32 years without a loss in the so-called Rumble in Ratliff, and held a 44-6 advantage in wins heading into the 2009 tilt.)

The 2009 season opened with great expectations for Permian. Gary Gaines, the coach during the Friday Night Lights era, had just returned after two decades away. When he left, following the 1989 season, Permian was on top of the schoolboy football world, having won the fifth of its six Texas state football championships that year and being named the #1 squad in the entire country by the National Prep Poll. He used the accolades as a springboard to college coaching, taking a job as an assistant at Texas Tech. He lasted four seasons in Lubbock, then bounced around the state, going from high school to college and back for the next decade and a half. Gaines never achieved the success at any other location or level that he’d had coaching schoolboys in Odessa.

Gary Gaines works out Permian players, 2009; photo via AP

The last Permian state championship came in 1991, and Gaines’s return inspired hopes that the school would end its title drought. The old coach and several of his players from the Friday Night Lights team—Chavez among them—gathered for a preseason ceremony at Ratliff to mark the coach’s comeback and the 20th anniversary of the book’s release. All that optimism had vanished by the end of the Odessa High game, though. A Lubbock pundit once wrote that the heat from the one-sided rivalry came down to kids on the Odessa High squad wanting to “avenge their fathers’ losses to Permian.” Well, lots of avenging took place that night in 2009.

The Bronchos crushed Permian.

“I have never seen Odessa dominate Permian,” the KHKX color commentator said at halftime, with Odessa leading 19-0. The final score was 26-7, the worst Rumble defeat Permian had suffered since 1963. Odessa High’s offensive star was Bradley Marquez, now a rookie receiver with the St. Louis Rams.

“What a difference 20 years makes,” the commentator said after the final gun.

Chavez’s night would get a lot worse than his alma mater’s. The police say that after Soto’s call, Jimenez announced to the party, “Brian and Rosemary are on their way and they want to kick our ass!” Soon enough, they arrived at the house of Jaime Castillo, who hosted the high school football listening party. As a crowd of partygoers and neighbors watched, Soto shouted that Jimenez’s current wife, Pamela Jimenez, was a “fat bitch,” then physically brawled in the street with Diedra Orona, a neighbor of the hosts. Witnesses told police Orona had the upperhand in the scrap before Chavez restrained Soto, got her in his SUV and drove away. Other than some scratches, torn clothes and hurt feelings, nobody got hurt. Jimenez called 911, later telling the cops that he was worried that the incident would somehow be used against him in a custody battle with Soto. Chavez was done playing peacemaker.

Before Odessa’s finest showed up at the Castillos’, Chavez returned—and this time he had reinforcements. According to the police reports, about 15 minutes after their departure, Chavez and Soto came back with two more male passengers in his auto and two other pickup trucks full of uninvited guests, all ready to rumble. Reports say that Chavez and the rest banged on the windows and doors of the house as everybody inside cowered. Then Soto forced her way through the front door and entered, yelling, “Where is that bitch that kicked my ass?” One witness told police that Chavez and “at least 9 or 10 men” ran in behind her; one victim said he counted 12 attackers.

The invaders spent several minutes beating the homeowners and their friends. Pamela Jimenez told police that when she looked for her husband, Soto’s ex, amid the melee she saw “two or three men” on top of him, pounding his head not only with fists but also with a “thing with little tea candles” that one of the attackers had grabbed from the living room. Castillo and Jason Orona, Diedra Orona’s husband, also took bad bashings.

“Brian walked in and hit Jaime in the mouth,” Tammie Castillo, Jaime’s wife, told police. Jaime Castillo, the report said, told police that Chavez and others were “punching him on his head until he passed out,” and that “when he regained consciousness his house was destroyed.”

Diedra Orona told police she saw her husband being beaten by the late arrivals as he was “trapped between the cushions on the couch and his face was covered in blood.” She said she dragged him into the kitchen unconscious and bleeding. Jason Orona could only identify Chavez among the assailants, saying he’d “seen him on TV.”

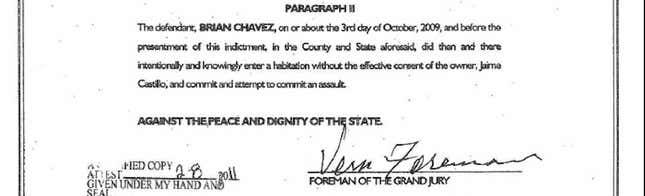

A detail from a 2010 indictment.

Neighbors, several of whom had called 911, told cops that after a few minutes of hearing the donnybrook going on inside the Castillos’ home, they saw lots of men run out the front door, jump into two trucks and speed away. Chavez and two other male attackers waited outside after the beatings, the victims said, while Soto continued cursing at them. Those four were the only invaders still on the premises when a fleet of squad cars and ambulances pulled up.

Police interviewed neighbors while several of the victims went to a local hospital. Officers reported blood in the living room and on all four arrestees.

The juvenile nature of Chavez’s actions became even more apparent when police figured out that one of the guys he brought along for the fight was Stanley Wilkins, a teammate on the 1988 Permian squad. Wilkins didn’t play a major part in Friday Night Lights, but his cameo appearances in the book do something to explain why Chavez would want him as a tag-team partner.

“Wilkins weighs 136 pounds,” Bissinger wrote, “and of all the kamikazes who dominate Permian and are eagerly willing to sacrifice their bodies for the great cause of football, he is the most fearless, or foolhardy.”

The other guy nabbed by the police at the scene was Brian’s younger brother, Jacob Chavez. The brothers, along with Soto and Wilkins, were booked on felony burglary charges; police never did learn who the people that neighbors saw scurrying into trucks and scooting away.

Residents in the region got to see Chavez on TV and newspapers as a result of the arrest. The local NBC affiliate, KWES-9, ran a story with the tease, “An Odessa neighborhood still reeling after a weekend ruckus lands some prominent residents behind bars.” The piece focused on “former Permian football star and Odessa lawyer Brian Chavez.”

Back in high school, after Permian lost, 22-21, to Midland Lee, a rival school from the neighboring and richer city, Chavez came home to find “For Sale” signs had been put in his front lawn by upset Mojo fans.

That was the last time Chavez’s renown worked against him in Odessa. Until this.

“It was like putting a cave man in the modern world.”

“I assure you when I left here I wasn’t planning to come back,” Chavez now says. “Nobody ever plans to come back to Odessa.”

So what brought him back?

“Harvard played a part,” he says. “Being away made me appreciate being home.”

Friday Night Lights makes a great case that he won the war just by leaving town in the first place. Getting out of Odessa, especially for academic purposes, was a near-foreign concept to the typical Permian kid. Bissinger portrayed Bridgitte Vandeventer, a cheerleader, as the most popular girl at Permian. She told Bissinger that the highlight of her life was being crowned homecoming queen. She didn’t bother taking SATs, and had no academic goal beyond maybe getting into the local junior college. And from everything the writer saw, Vandeventer was “clearly a role model” to her peers.

As the parent of a Permian student says about the school in Friday Night Lights, “It’s not popular to be bright.”

Yet Chavez was both. In an interview after the movie version of Bissinger’s book was released, Ken Brodnax, the longtime lead columnist for the Odessa American, said Chavez let everybody know from an early age that he wanted to go to an Ivy League school. That’s not a goal a lot of Permian kids make happen: Chavez was told that at the time he attended, he was only the second student from Odessa to ever study at Harvard.

Bissinger all but accused Permian coaches of hindering Chavez’s attempt to get into Harvard. Nobody from the football staff at Permian, he wrote, contacted the college’s coaches on their player’s behalf, a standard role for high school coaches. And after a Harvard coach requested game film of Chavez, Permian coaches shipped a tape of the only game from his senior season that Chavez didn’t play in.

Not everybody in the book roadblocked the brainy and brawny student. Bissinger wrote that Chavez got support academically from LaRue Moore, an English teacher who encouraged him to chase his dream of getting to Harvard.

Moore understood that writers “did not pack the stands with 20,000 people on a Friday night” or foment civic pride, and knew that, “No one dreamed of being able to write a superb critical analysis of Joyce’s ‘Finnegans Wake’ from the age of four on” as much as they did playing under the Ratliff lights. She was well aware of the wage discrepancy between teachers and coaches, but didn’t mind that the community valued the game more than her discipline. Moore, who had a masters degree and had already been teaching for 20 years by 1988, was making $32,000 a year then. Bissinger said Moore spent “hundreds of dollars out of her own pocket” to buy books for students; Gary Gaines, in his first run as Permian’s head football coach, was getting $48,000, and was promised “a new Taurus sedan” every year.

Odessa, Texas, 2006; photo via AP

Moore, now retired from teaching but still living in Odessa, wasn’t in it for the money. She recalls that Chavez made her love her job.

“When he decided he wanted to go to Harvard, he was going to do anything it took,” she says. “He was a wonderful student.”

The way Chavez now tells it, most of the happiness he got out of Harvard came from just getting there. His admission was only time he felt accepted.

“You could have done a dang anthropology dissertation on me moving over there from Odessa,” he says. “It was like putting a cave man in the modern world. I felt just so different from the people I went to school with at Harvard.”

He says Harvard forced him to be aware of his race “for the first time since third grade.” He was born to Mexican-American parents in El Paso, an overwhelmingly Mexican border town where his ethnicity was never an issue. But that changed when his family moved to Odessa so his father, Tony Chavez—a former police officer who’d just finished law school—could accept a job as a prosecutor in the Ector County District Attorney’s office. He would soon open his own law practice in town. The racial divide between white and in the region in the late-1970s was still as wide as portrayed in Giant, James Dean’s 1956 West Texas epic. In Odessa, though, both of Chavez’s parents had good jobs, so they got to live, he says, on “the white side of town.” It took a while to get his overwhelmingly Caucasian classmates to accept him.

“Not to brag, but in El Paso I was the most popular kid in third grade,” he says. “Then we move to Odessa and for the first time I experienced meanness and ugliness toward me. I didn’t get it at the time, but now I see it was racism. But everybody I had to fight later became my friend, and I only won them over by being better than them at sports and smarter than them, and because my parents had as much money as theirs. I gave them nothing to fit me into that box they had for all Mexicans. So slowly but surely I became ingrained in their culture, accepted in that culture.”

From the start, he embraced the locals’ high school football fervor. He remembers being afraid to ask his new classmates what it meant that “MOJO” and “Permian” were stenciled on all their t-shirts. “I waited a month,” he says, “And they said, ‘That’s the high school football team!’ In El Paso, it was the Dallas Cowboys. In Odessa, it was the high school team. You wanted that. I wanted to play, too. And from then on the boulder kept rolling.”

His gridiron prowess played a huge role in the Permian community’s embrace of him. It was something he couldn’t take with him to college.

“I was voted captain of the football team, got voted prom king, dated the cheerleader, was named salutatorian,” he says. “I mean, like in El Paso, my ‘Mexicanness’ wasn’t a thing. Then I get to Harvard, the most liberal place on earth, and it was—boom! Back to the bottom rung! So I had to start back up trying to win them over, like I did in third grade. Only I didn’t do that.”

Brian Chavez, second from left, at the 2004 premier of Friday Night Lights; photo via Getty

The fight for acceptance was a lot different this time around. Everybody at Harvard was at the top of their class academically. “And my parents weren’t as rich as these people’s parents,” he says, laughing. “I mean, now I was in school with Roosevelts and Rockefellers.”

Perhaps most profoundly, he no longer had football on his side at Harvard. Chavez went out for the junior varsity team—freshmen weren’t allowed to play varsity—but quit days after his first practice, later telling folks that he’d realized the Ivy League version of college football wouldn’t match up to his Texas high school football career as far as talent level, crowd sizes, and overall intensity.

He always felt alienated. Harvard allows third-year students to leave Cambridge to study topics not offered by the school—the cliched “junior year abroad.” Chavez says he felt like a foreigner his freshman and sophomore years, however, so he spent his sabbatical back in Texas, enrolling in the Mexican-American Studies program at the University of Texas at Austin. He ignored the football games at UT, instead adopting a very Ivy League pastime.

“I played rugby,” he says. “I loved it.”

He went back to Harvard for his senior year, did an honors thesis to meet cum laude criteria, and then accepted a scholarship offer from Texas Tech’s law school in Lubbock, 140 miles to the north of Odessa. He founded the Mexican-American Law Students Association at Tech, then got further in touch with his heritage by spending a year in Mexico after graduation. And all of this set him on a path quite different from the one a reader of Friday Night Lights might have imagined for him.

“I could have tried Wall Street, or a big New York or Houston law firm,” he says, “But our firm basically had cornered the market for Hispanics in Odessa and Midland, and that’s about 240,000 people, because there’s so few Mexican lawyers besides us. So I could make as much money as anybody I went to school with and not have to work like a New York lawyer, and be close to my family. And I’d been away, so I knew what that was like. Maybe being at Harvard and so far away, being so isolated, made me appreciate it or long for it. I just decided from a quality of life standpoint, this was an easy decision.”

After Mexico, he went home.

“I was the big fish.”

The civil suits came first and fast. Less than three weeks after his home invasion arrest, the Castillos, joined by the Oronases, sued Chavez. In their complaint, according to a report in the Odessa American, they claimed that he and his posse “struck Plaintiffs with their fists, kicked them with their feet, struck them with fixtures and statues from within Plaintiffs’ home, and held Plaintiffs down with their bodies.”

“Several Plaintiffs were assaulted until unconscious,” the suit said.

Jaime Castillo told the court that because of threats made against them by Odessans loyal to Chavez, his children were “afraid to be in their own home.”

In preliminary hearings, Daniel Bates, hired by Chavez to defend him in the civil case, told the court that the brouhaha was an example of “mutual combat,” sticking to the story Chavez had told police shortly after the incident—that all the fighting was among consenting adults. But the sides started settlement talks immediately and, because of Chavez’s local fame, the negotiations were far more public than in a typical personal injury case. The Odessa American gave readers extensive coverage of the brawl and related legal cases, which went on for months, and routinely cited Chavez’s back story (i.e., “a former Permian football star [who] was featured in the book Friday Night Lights’”).

In March 2010, Chavez paid a reported $360,000 to those given the beatdown to settle the cases. In return for the cash, the victims signed so-called “affidavits of nonprosecution,” which essentially tell prosecutors that signees won’t cooperate with a criminal case. So after the settlement, Chavez thought he would have no further trouble.

He was wrong.

Director Peter Berg and Permian alums James “Boobie” Miles and Brian Chavez under the lights, 2004; photo via AP

Chavez had friends in high places all over Odessa, including in the local court system. Perhaps if the whole town hadn’t been paying attention, those connections would have helped. Folks were watching, however, and so the case couldn’t just disappear. First, Judge John Smith recused himself, citing his relationship with Chavez. Then District Attorney Bobby Bland begged out of prosecuting the case, also citing a friendship with the accused.

The replacement judge brought in Wesley Mau, an Austin-based prosecutor from the state attorney general’s office. Mau says his only previous trip to Odessa had come a year earlier, when he was tasked by the state to prosecute a murder case that dated back to 1994. The jury accepted Mau’s recommendation to give the death penalty.

“I knew from experience that after a settlement with [affidavits of nondisclosure], the criminal case gets dropped,” says Chavez. “That’s how it is. But when I heard the state was taking over the case, I knew I was in trouble. They don’t mess around.”

Reached at his office, Samuel Sanchez, the Fort Worth attorney who represented plaintiffs in the civil suits against Chavez, declined to answer questions about the case “because of confidentiality agreements.”

Mau ignored the agreements signed by the alleged victims and brought the case to a grand jury.

“I understood there was a settlement,” he says. “But that doesn’t have anything to do with me.”

The victims cooperated with Mau, and the prosecutor now says he thinks he eventually got a straight story from Chavez about what took place after the game.

“He had lied to the police, but not to me,” says Mau.

Chavez had told police that the brawl started outside the house; Mau didn’t buy it. And whether the brawling was consensual became inconsequential, the way Mau saw things, once Chavez entered the Castillos’ home without permission. In the eyes of the law, when Chavez and his posse went through the front door, they crossed a legal line. The grand jury indicted him for burglary of a habitation with intent to commit assault, a felony. He faced a punishment of 20 years in jail and a $10,000 fine.

Mau says that he took into account that Chavez had never been arrested before. He offered him a deal with no jail time, but the maximum fine, 340 hours of community service, and five years of supervised probation. Mau also told Chavez that if he took the deal, the state would not pursue various other charges that had been hanging over his head since the ruckus, such as witness tampering and making a false report to a police officer. And while Mau still believes witness and victim testimony that Chavez had lots of help pounding partygoers—“It was eight or nine guys,” Mau tells me—he only prosecuted Chavez and the three others arrested with him on the night of the brawl (Wilkins, Soto, and Jacob Chavez). All defendants were offered similar deals.

On Dec. 16, 2010, Chavez copped the plea. The others followed suit.

“I was the big fish,” he says. “I was the guy they wanted to get. I had too much to risk, and I didn’t want to put my friends at risk either.”

As the settlement was filed with the court, his attorney, Mike McLeaish, told the media that Chavez was sorry and that his client had suffered enough.

“Until this indictment, no person that I know of had led a better life than Brian Chavez,” McLeaish said. “He was well-known and well-liked at Permian and at Harvard University and Tech Law School. He is a nice guy.”

The message didn’t take. The Texas bar’s disciplinary board took up the Chavez case and determined that his offense met the legal definition of both an “intentional crime” and a “serious crime,” which rendered him eligible for permanent disbarment. As it was, the board moved to suspend his license for the length of his probation—until, that is, Dec. 15, 2015. In its ruling, the bar association ruled that if for any reason his probation was revoked, then “Brian Jose Chavez should be disbarred.”

Chavez still has hard feelings for the plaintiffs, who, he says, took his money and “went back on their word.” But he thinks it was right to take Mau’s deal. If he went to trial and got convicted, he says, he thinks it likely that he would have been permanently disbarred. And he knows that he wasn’t all that innocent.

“I think it all got exaggerated, to tell you the truth,” he says. “But, basically, we whupped ’em, and got punished for whupping ’em.”

“Nothing is like high school football, especially at Permian.”

As it worked out, the kid who came off in the book as the most eager and prepared to get out of town is the only one who ended up there. Not one of the other five Permian players that Buzz Bissinger used as main characters still lives in Odessa.

Even the Permian kid that the book painted as most inert, Bridgitte Vandeventer, got away and stayed away. According to a story in the Odessa American about the Class of ‘89, Vandeventer married a South African, and, when he got homesick, moved with him to Johannesburg. He bought her a ranch to show his appreciation for leaving West Texas, and then discovered diamonds on the property. Vandeventer, the class’s homecoming queen and cheerleader, told her old hometown newspaper that she “accidentally” ended up a diamond mine owner.

Chavez sort of struck gold after losing his lawyer’s license. He founded a trucking company and bought up Odessa real estate to take advantage of the biggest oil boom to hit West Texas since the 1980s, then invested in a restaurant and a ballroom. He also got engaged to Soto.

“I look at it as kind of a blessing in disguise,” he says of the break from lawyering, “I’d put all my eggs in the lawyer basket. It was good to diversify.”

The state bar told him that he was eligible to practice law as of this week. On Thursday, the clerk’s office of the Texas Supreme Court mailed out his bar card and law license—frame and all, just like he delivered it. To prepare for this day and those yet to come, Chavez ordered a passel of suits from the Men’s Wearhouse in Midland. “It’s been a while since I had to wear one,” he says.

He still pays attention to Permian football, like everybody else in Odessa. He followed the squad with more emotion this season than he had since he played. His nephew, Anthony Chavez, was a senior defensive back and special teamer for Mojo. Brian Chavez coached Anthony on youth leagues all the way up to high school. “He wore my jersey number all the way growing up,” says the proud uncle.

An extra walks in front of a stand full of dummies as Friday Night Lights is filmed, 2004; photo via AP

Permian was supposed to contend for a state title this fall, which marked the 25th anniversary of Friday Night Lights. The squad had 19 seniors starting. Mojo was undefeated through nine games, including a 57-7 spanking of the Odessa Bronchos in the Rumble in Ratliff. But Permian’s season ended in the second round of the divisional playoffs, with an upset to Amarillo Tascosa, which heading into the contest had lost 16 games in a row to Permian, a streak that dates back to the 1960s.

Chavez didn’t get in any trouble after that loss. “I was just a big cheerleader,” he says.

The Odessa American wrote up the season-ending game like an obituary, and accompanied the story with a photo of Permian players holding hands and crying, much like the scene Bissinger captured after an upset loss during Chavez’s senior year.

“We can never go back to high school football,” safety Jax Welch, who will graduate this year, told the newspaper after the Amarillo Tascosa defeat. “Nothing is like high school football, especially at Permian.”

A lot of things about Bissinger’s book still hold, and among them is this: football remains the king in Odessa. The income gap between those teaching literary classics in a classroom and those putting kids through the Oklahoma Drill on a practice field has only widened in the years since Friday Night Lights was published. Current head coach Blake Feldt, brought in after Gaines left under pressure, was lured to Permian by a base salary of $110,399, plus a $7,200 car allowance. (The Permian coach always gets perks from the booster club, too.) Feldt had been a football coach for 13 years; a teacher with that same amount of experience at the time got $49,734, with no transportation subsidy, and, alas, no booster bonuses.

In 2013, the school board approved installation of a $2 million, 50 foot-by-26-foot video scoreboard for Ratliff Stadium.

No matter what the rest of the world thinks about misplaced priorities or lack of perspective, Chavez, at 45, still believes in the Permian way. It turns out the guy so admired a quarter century ago for not putting all his eggs in football’s basket sees nothing tragic in those who do.

“What made the Permian program, what’s so great about it, is that in Odessa, as a third grader you idolized the Permian middle linebacker or safety or receiver. That’s who you wanted to be,” he says. “And that’s a goal you can actually attain! How great is that? A goal you have in life is actually attainable! All you have to do is you just keep playing with your buddies and your friends and you actually attain your goals! In Odessa, you can do that! But, you grow up somewhere else, wanting to be Troy Aikman? You’re never going to be Troy Aikman.”

There are signs that Chavez has had an influence on those who followed in his cleat-steps—and not just because latter-day Permian players are no doubt aware of Friday Night Lights. (The locals have been complaining about their portrayal since the book was hot off the presses.) In 2013, Permian’s captain, Jorrion Wilson, who ran for 2,700 yards and scored 38 touchdowns as a junior and senior, graduated at the top of his class, and with all the college options Chavez had 25 years ago.

He turned down lots of football scholarships to accept admission to Harvard.

Chavez, the last Permian player to make it to Cambridge, won’t take any credit for Odessa’s latest export. But he will admit having a hand in his nephew’s decision-making about life after Mojo. Anthony Chavez is deciding on a college. He’s told his uncle that he plans to stay in Texas, and that he’s done with football.

“He thinks,” says Chavez, “he’s going to play rugby.”

Know something we should know? You can reach the reporter at [email protected]. Illustration by Jim Cooke.