Matt Paré, a catcher with the San Francisco Giants’ Single A affiliate in Augusta, Ga., doesn’t seem to mind sharing a two-bedroom apartment with three other guys. “Since half the time we’re on the road, it’s only 15 days a month,” he says. On the road, he shares a hotel room with just one of those roommates. This lack of personal space isn’t especially tragic, but it’s a far cry from the glamorous lifestyle you might imagine a professional athlete to lead.

While big free-agent contracts and first-round signing bonuses get the headlines, for most players the reality of playing baseball is very different. There isn’t a lot of money to be made playing in the minors—monthly salaries can be as low as $1,100—and the problem is getting worse over time. (Once inflation is accounted for, minor-league salaries have lost more than half of their value over the last 40 years, during which time major-league salaries have increased by 2,500 percent.) Take into account that something like 17 percent of draftees and even fewer international signees ever make the majors, and you end up with a bunch of dudes out there playing professionally and subsisting on shockingly low salaries.

Thanks to a still-pending class-action lawsuit filed by former minor-league ballplayers in 2014 and an outrageous bill recently proposed in the House of Representatives, more and more people are taking notice of all of this, but it can still all seem rather abstract. In an effort to better understand these salaries have on real people—and lightly inspired by Refinery29's Money Diaries—we talked to a real minor leaguer.

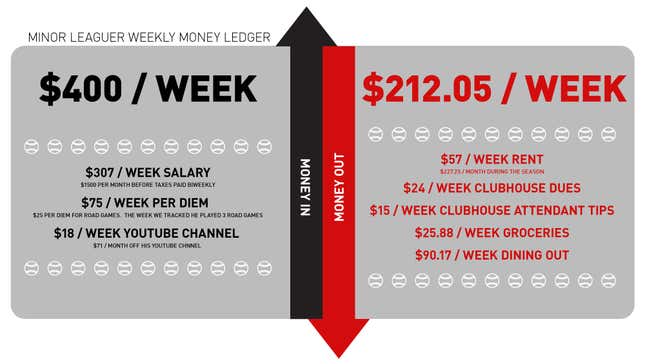

Matt Paré, a 26th-round pick in the 2009 draft who’s currently catching for the Augusta GreenJackets, tracked his spending for one week recently. It was a representative one, during which he played three days at home and three days on the road, and had one off day. Here’s what we learned:

Income

Like most Single-A players, Matt makes $1500 per month. After taxes are taken out automatically, that works out to $614.25, paid twice monthly. Players are not responsible for paying for health insurance. Paré is only paid during the season, not for the offseason or for spring training. As a relatively low pick, Matt got a $1000 signing bonus which he says ended up around $600 after taxes. For road games, he and the other Single-A players get $25 per diem.

Matt also has a Youtube channel that he’s trying to monetize. Right now, he brings in $71 per month through a crowd-sourcing site tied to the channel.

Housing

During the season, Matt lives with three other teammates in a two-bedroom apartment in Augusta. Two of them share a room, one guy gets his own room, and Matt sleeps in the living room. They split the rent equally, each paying $227.25 per month, but the housemate with the single room covers Internet and cable.

“I didn’t want to pay more,” Matt explains. “I said I’d gladly take the living room.”

Sometimes, though, the extra cost is worth it. When we spoke, Matt’s girlfriend was visiting from out of town. “I helped pay for some of the cable bill this month,” he said, “so I could take my roommate’s single room, so we’re not sleeping in the living room together. Just so we could have a little more privacy.”

This past offseason, Matt moved to San Diego from Boston, where he went to school. In Boston, he taught baseball in the offseason but “was kind of just sick of the cold.” For his first offseason in San Diego, he lived with a cousin, who let him stay for free in exchange for help training her English bulldog.

This year, Matt and his girlfriend plan to get a place together in San Diego, where he’ll need a more formalized offseason gig to make rent. He says he’s “definitely” concerned about contributing to their shared household expenses, but that he’s going to be able to do so.

“I’ve looked into a bunch of things to do this offseason,” he says. “Dog walking, being a substitute teacher, there are so many different things you can do in the offseason for a job. Be an Uber driver. Do Postmates, or something else that’s less stress on your car. Or teach baseball lessons.”

Clubhouse Dues

The cash demanded of most minimum wage minor leaguers to cover the clubhouse attendant’s salary isn’t an issue for Matt, at least not at home. “The Giants are actually really good about this,” he says. “For the first time this year we don’t have to pay clubhouse dues at home.”

He still tips the clubbie—$10 for every home series—both because it’s accepted standard practice and because it ensures he can have early dibs on the leftover food from the catered spreads on game days. On the road, he still owes $8 per day in dues in addition to a tip for the local clubbie ($5 at the end of the series).

Matt credits the Giants’ concession on this issue for a future trickle-down impact on the overall farm system.

“That’s how you get the homegrown talent.”

Food

In addition to getting rid of home clubhouse dues specifically, Matt praises the Giants’ treatment of minor leaguers generally. And with salaries so low, this primarily refers to providing free food.

“I feel like we live like kings when we’re at home,” he says. “We get two meals per day that are catered by Whole Foods. And there’s a lot of leftovers, so I’ll wait around till after everyone’s eaten—I’m not gonna take food when everyone hasn’t eaten—and I’ll grab a couple things that I can use for breakfast in the morning. That way I don’t have to go out for a meal before I go to the field.”

When he’s at home in Augusta, Matt eats five eggs with whatever leftovers he snagged the night before (“quinoa or vegetables”) for breakfast. For the week he tracked his spending, the eggs were already purchased—he and his roommates buy eggs in extreme bulk to accommodate the roughly 65 eggs they consume each homestand—and lunch and dinner were provided by the team. For the first two days of the week, he spent no money at all.

On the third day, he went to Whole Foods for lunch, and to stock up on ingredients for bulletproof coffee, requiring him to splurge $34.88 for stir-fry, MCT oil and butter.

His off day cost $28.93 for lunch at a Mexican food restaurant and a 70th birthday for the team’s bus driver.

Without the Giants’ careful catering, road trips are much more expensive, although offset by his per diem: a $16 lunch, a $17 late night pizza delivery, another lunch at $11.24, and $8 towards a team getaway meal at the end of the series.

Total

All told, Matt spent $155.05 over seven days. Add in a quarter of the month’s rent, and that brings us to roughly $212.05 for the week. And that’s how you make it as a minor leaguer.