When I thought my son was old enough to understand the concept of "no means no," I said those exact words to him when he appeared unwilling to back away from a confrontation-in-the-making. This kind of situation arose frequently—the playground, a playdate, just being around his younger sister. "Jonny said he doesn't want to play that game anymore," I'd say. "No means no. You can't force your will on him. Find something you can both agree on."

He was three, maybe four when I started using "no means no." I was trying to teach him about respecting the desires of others, even when those desires conflicted with his own. Now that he's 14, I'm fairly certain he had no idea what I was talking about.

As he grew, I emphasized the need to respect others' personal space. It was a shift in focus, from diffusing a potential conflict to preventing a conflict in the first place. "Don't be all up in someone's business if they don't want you there." I didn't say those exact words—he would have laughed in my face if I had—but I talked to him about privacy and autonomy and consent.

Not easy ideas for adults to grasp, much less teenagers.

But I persisted. Even when his eyes glazed over. Even when he mumbled, "Yes, Mom, I get it" as his fingers fiddled on his phone. Even when he tried to escape to his room with the door closed. I persisted because I believed that if I talked about these things with him from the start—and I reinforced them as he grew up—they would feel natural and comfortable to him as moved into his teens, and then adulthood.

And especially when he became sexually active.

I don't want my son to grow up to be a rapist.

Just writing those words is startling. I've never been sexually assaulted or threatened with sexual assault. There's no history of sexual assault in our family. The women in my family, and in my husband's family, are strong, independent, and successful—just the kind of role models you'd want for your sons and daughters. Why would I worry that my son would someday force a woman to have sex with him, against her will?

Because outside our family, he has been and will continue to be bombarded with images and words that encourage boys to view girls as weaker and dumber and less worthy of respect. As objects of sexual desire to be judged by their looks and discarded when no longer useful. He's been told that rape jokes are funny and anyone who doesn't think so just doesn't have a sense of humor. That's why.

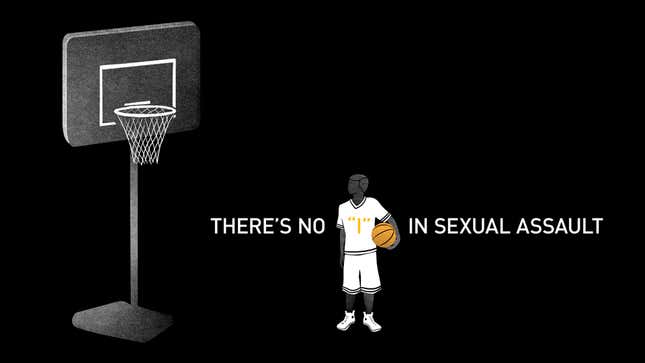

My son is an athlete. Basketball is his main gig, but he also runs track at school and plays flag football in a rec league, because no way in hell would I let him play tackle football. He's a 5-foot-6-inch white kid who hasn't yet had his big growth spurt, but still dreams he has a chance to play in the NBA. Or a European League. Somewhere. Anywhere that will pay him to play basketball.

Left to his own devices, he'd play or watch sports 24 hours a day. He may be on the young end of the ESPN demo, but he's no less a devotee of SportsCenter. And he'll sneak-watch First Take when I'm not around and then try to convince me that Stephen A. Smith has some interesting things to say. (He doesn't.)

My son has watched as women who've accused athletes of sexual assault—backed up by credible, corroborating evidence—have been cast aside by the athletes, their coaches, their athletic departments, and their schools. Time and again, he's seen adults in positions of authority willfully ignore, lie, misdirect, and cover up for athletes to protect their programs at the expense of victims.

What message does that send? It tells my son that if you have a talent that is valuable to people in power, you can treat women however you want. It tells him that he's entitled to sex with or without a woman's consent. It tells him that women's autonomy isn't important and their voices can be ignored.

That disheartening but stark reality undermines everything I've tried to teach my son.

The latest incident hits particularly close to home. Last week, the student newspaper at Duke reported that Rasheed Sulaimon was dismissed from the school's basketball program in January, more than a year after two women students publicly accused him of sexual assault. Neither student filed a formal complaint, purportedly for fear of a backlash by the team's rabid fan base. But the Duke Chronicle also reported that athletic department officials, head coach Mike Krzyzewski, and the Dean of Students learned of the accusations against Sulaimon last spring. Questions remain about what Duke officials knew, when they found out, and what steps they took to address the allegations.

My husband is a Duke Law grad. He was on campus in Durham when Duke won its first national championship in 1991. His closet is filled with Blue Devil T-shirts and caps. He's a proud Duke fan, in an everyone-else-hates-Duke world. He's shared that passion with our son. It was a tough day in our house.

If Coach K knew that two women had accused Sulaimon of sexual assault, he was obligated to report that information to university officials. Title IX legally compelled him to act, but his standing at Duke compelled him even more so.

How are we to teach our sons to treat women as equals who can give and withhold consent, when their stories of violence and violation are silenced by powerful and respected men?

We sit them down and talk about sexual assault. We explain that when a man wants sex and a woman doesn't, and the man forces her to, it's sexual assault. We explain that when a woman seems interested in sex but then changes her mind, she hasn't consented to sex, and forcing it on her is sexual assault. We explain that sexual assault is harmful for men and women, and can haunt you for the rest of your life.

But it's not just about teaching our sons what not to do. We also have to give them room to experiment and develop healthy relationships, sexual or otherwise. We need to provide them with a comfortable space to talk to us about what they experience in their relationships and what they see and hear from friends, classmates, and in the media. We encourage them to stand up and say no to coercive behavior and we admonish them when they don't.

We tell them that if Rasheed Sulaimon forced women to have sex with him without their consent, he was wrong. We tell them that if Duke officials learned about the women's accounts and did nothing—even for a short while—it was wrong. We tell them that what happened at Florida State and Oregon and Vanderbilt and Steubenville High School was wrong.

We tell them that no sport, no team, no player is more important than treating others with respect and doing what's right.

Then we send them out into the world and hold our breath.

Wendy Thurm writes about sports and other things. She practiced law for 18 years but is now almost recovered. She can be found on twitter @hangingsliders.

Image by Jim Cooke.

Adequate Man is Deadspin's new self-improvement blog, dedicated to making you just good enough at everything. Suggestions for future topics are welcome below.