The internet abounds in cheerful content, and last fall one of its most cheerful stories started like this: In a press release, the University of New Hampshire announced that an elderly librarian had died—and left the school a shocking donation of $4 million.

The librarian’s name was Robert Morin, and though he’d worked at UNH for decades no one knew he’d saved that kind of money. The details quickly went viral. “This beautiful gift is one for the books,” the Huffington Post gushed. “Living a frugal life pays off,” People opined. “He was a librarian with a multi-million dollar secret,” an anchor intoned on ABC’s World News Tonight, “and he left it all to the place he loved the most.”

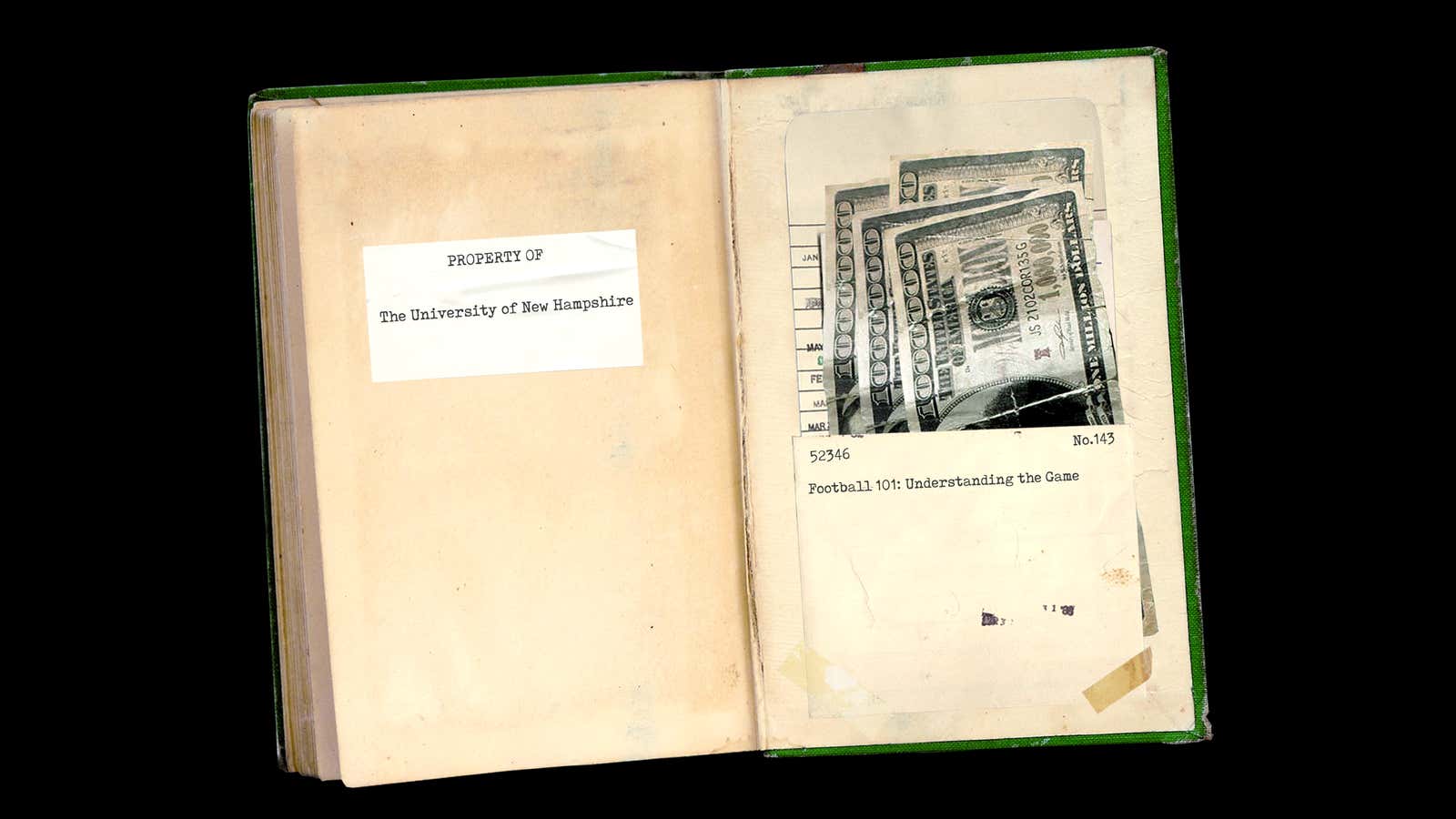

That’s where most people left Robert Morin. A second, smaller wave of coverage focused on UNH’s troubling decision to funnel only $100,000 of his money to the library, even as it committed $1 million of it to a video scoreboard for its football stadium. But the full story is more troubling still. Through a series of interviews and public records requests, Deadspin has uncovered the 17-month backstory to Morin’s bequest. Like so many schools, big and small, UNH spent wildly on its athletic department. The university went a step further in trying to engineer a public relations victory, deceptively connecting a fragment of Morin’s life to its football splurge. The media eagerly repackaged the story as an inspirational fable.

What got lost in this circus, though, was the man who caused it in the first place—a strange and amiable human being whose life was far too eccentric to fit in a press release or piece of digital flotsam.

The basic facts behind Morin’s viral fame are true. He really did work as a librarian for 49 years, he really did amass a fortune of $4 million, and he really did keep that fortune a secret. After Morin found out in 2014 that he had colon cancer, he spent his final months in an assisted-living center. When his fellow librarians came to visit, they fretted he wouldn’t be able to afford the facility.

“I assured them,” says Ed Mullen, Morin’s financial adviser, “that they didn’t need to worry about that.”

Morin’s story didn’t turn shady until the university got involved. UNH administrators learned of the bequest soon after his death on March 31, 2015, and they wasted no time in deciding how to spend it. The school had earned quite a reputation for spending under President Mark Huddleston. There had been small extravagances, including $65,000 for a redesigned logo and $17,570 for a 16-seat table. There had been large ones, including $1.9 million for a student-athlete center and $6.5 million for an outdoor pool. But one of the biggest projects—and a crucial component in the campus’s master plan—was renovating the football stadium. The UNH Wildcats, an FCS team, had played in their 6,500-seat home for decades. In 2014, however, Huddleston announced plans for a $25 million upgrade, financed by $5 million in fundraising and $20 million in loans, that would nearly double the number of seats, nearly quadruple the number of bathrooms, and introduce casual fan-friendly options like an air-conditioned victory club and all-you-can-eat buffet.

One feature the administrators discussed in 2014 was a high-definition video scoreboard, but they decided to nix it when the budget got tight. That changed once they heard about Morin’s donation. It was an enormous sum, of course, but more important, it was an unrestricted sum. Most higher ed philanthropy comes with strings. (I was an actor; give my money to the theater department.) In a recently completed five-year fundraising campaign, UNH collected only $9 million in unrestricted funds, and almost half of that total came from Robert Morin.

Morin’s bequest, in other words, provided a rare and unencumbered chance for Huddleston and UNH to express their priorities. And what they wanted was that previously considered scoreboard. Things moved quickly to ensure it would be ready alongside the other stadium upgrades, just in time for the 2016 season. On September 1, 2015, Mark Geuther of UNH’s Facilities Project Management summed up the latest developments in an email. “President Huddleston received a undesignated gift to the University,” Geuther wrote, “which is being designated for the design, purchase and installation of a video board. . . . The current budget for the video board scope of work is $1 million.”

The scoreboard campaign proceeded on two fronts. The first was construction. By January 2016, UNH had retained a pricey consulting firm that specialized in stadium audio and video; by February, they were reviewing multiple bids. While the bids included at least one cheaper option, the school chose a 30-foot-by-50-foot LED display from Mitsubishi.

The second front involved the publicity operation. Inside UNH’s media relations office, staffers were buzzing—not just about Morin’s gift but about its narrative possibilities. On March 29, Erika Mantz, UNH’s director of media relations, circulated a sample media campaign, an intricate plan of attack that involved at least 12 university employees and mapped their work down to the minute: a press release and coordinated media pitches; separate emails to prospective students and to alumni and parents; and the mandatory social media push.

That plan received an enthusiastic response, though at least one administrator worried about the optics. By this point, Huddleston had finalized the breakdown of Morin’s money: $1 million to the scoreboard, $2.5 million to UNH’s career center, and $100,000 to the library, with the rest to figure out later. “[T]he gift is so large,” Debbie Dutton, president of the UNH Foundation, wrote in an email, “and he worked in the library and only a relatively small amount is going to the library.”

A solution would soon present itself. In that same March email, Mantz wrote, “I have two people to contact tomorrow (per Theresa) who can tell me more about Mr. Morin.” (The reference was to Theresa Curry, another UNH administrator.) One of those people was Ed Mullen, and one of the things he told Mantz was that Morin had taken to watching football at the assisted-living center.

Mantz gathered more details about the media campaign’s star, and they informed the UNH press release that finally broke the news on August 30, 2016. The release provided an inspiring glimpse of Morin: a simple man, a dedicated employee, an alum. It also linked his biography to the newly funded projects. That was easy enough with the library. But the scoreboard required some finesse. “Another $1 million will support a video scoreboard for the new football stadium,” the release said. “In the last 15 months of his life, Morin lived in an assisted living center where he started watching football games on television, mastering the rules and names of the players and teams.”

This was a remarkably cynical bit of marketing. After all, Mantz had said in March that she still needed to dig into Morin’s life—and that was many months after the scoreboard had already been revived. The librarian’s fandom had absolutely nothing to do with the scoreboard, but through a careful and shameless juxtaposition, UNH implied that it had. It made for a tidy, touching story. It also gave the university some cover from any criticism that might appear.

The news of Morin’s bequest traveled farther and faster than anyone could have hoped. In interviews, Mantz volunteered the football connection when the scoreboard came up; the media, even good newspapers that put good reporters on the assignment, nodded along. “The $1 million for a video scoreboard also is linked to Morin’s interests,” the Boston Globe noted. “After he entered the assisted-living center, Mantz said, Morin became a football aficionado—learning the rules and memorizing the names of the players he saw on television.” The same message surfaced in the New Hampshire Union-Leader: “UNH spokesman Erika Mantz said that, in the last 15 months of his life, Morin lived in a Durham assisted-living center where he started watching football games on television. He mastered the rules and names of the players and teams.”

Throughout the first part of September, the tale of Morin’s pigskin obsession continued to spread, with the sloppiest aggregators turning him into a fan of the Wildcats themselves. But in truth, Morin’s late-life turn to football didn’t explain the scoreboard or, really, anything else. In fact, the more you know about Robert Morin, the more noxious UNH’s marketing strategy becomes.

One rainy morning, while Morin was still alive, a UNH student named Sky Gidge visited him at his library cubicle. Morin was an odd but familiar figure on campus—just over five feet tall, just over 100 pounds, someone who was known for his worn-out sports coats and his horseshoe of wispy hair, whom students would often see smoking a pipe outside the library. Gidge decided to profile Morin for a student magazine, and during their interview he asked the librarian if he liked people.

“I get along with people,” Morin replied. “Aristotle found that one of the goods was friendship. He found friendship to be very important. I don’t.”

That exchange was pure Robert Morin—generous, funny, erudite, and stubbornly independent.

Morin was born in Nashua, New Hampshire, in 1938. He was also born with a curved spine and a clubfoot, and he walked with a severe limp his entire life. His parents were working class. (They never owned a house together, or even a car.) His younger brothers were, too. But Morin realized from an early age that he was different. “He was an amazingly bright person,” says Maurice Arel, who used to walk with Morin every day to school. The boys also sat together, and Arel marveled at how his friend could finish a test before everyone else yet still earn the highest grade. Once they got to Nashua High School, however, Arel started chasing girls and playing football, eventually becoming a starter on the varsity squad. Morin didn’t seem interested in either pursuit; he preferred reading or studying alone. The two saw each other less and less, until their relationship was simply saying hi in the halls at school. “He kind of disappeared,” Arel says.

In 1955, Morin graduated from Nashua High as an honor student. The local paper ran his picture, which captured a head full of thick, slicked-back hair, along with the sweet and muted smile he’d flash for the rest of his life. That fall Morin enrolled at the University of New Hampshire, the first and only person from his family to attend college. It took him eight years to finish, mostly because he had to keep dropping out to work. Money had become even scarcer when his parents divorced, and after their split Morin quit speaking to any family member except his mother. Yet something happy did emerge from this period: one of his jobs was a part-time position at the UNH library, and Morin liked it so much he got a master’s in library science, then joined the staff full time in 1965.

Morin’s task was cataloging the new media that swept into the library, which initially meant typing their information onto small cards, until everything switched to computers. His broad knowledge base and reflexive thoroughness made him an incredibly good cataloguer. The toughest items—foreign titles, sheet music—always landed in his cubicle. Everyone who knew Morin says the same thing: the library was his life. But they mean the job more than the people. He was kind to his colleagues; he was happy to make small talk, to tease, to burst into a silly song. But he rarely went beyond that, even if that required him to skip staff meetings or to duck out of deeper conversations about family or politics. He wanted to keep his life simple and free.

This isn’t to say his life was empty. Morin approached his hobbies like he approached his cataloguing, though perhaps it was the other way around. While he’d avoided going to movie theaters for more than a decade, in 1979 he invested in an exciting new technology: the VCR. At home he started watching three or four movies a night and kept it up until he’d seen 21,000 films. (At some point he went back and counted.) His television quit working in 1997, but instead of fixing it Morin flipped to a new pursuit: reading every American trade book that had been published in the 1930s, in chronological order.

Morin was able to practice these hobbies cheaply thanks to his connections in the interlibrary loan department. He did everything cheaply. He didn’t have a credit card. He didn’t travel, preferring to spend vacations at his small ranch home a few miles from campus. While he’d enjoyed routines even as a teenager, the desire intensified as he grew older. Each day, breakfast came from one of the library’s vending machines; lunch was a sandwich stored in the pocket of his sports coat; supper was a frozen dinner.

One byproduct of this rigid and frugal life was that money started piling up. In 1971, Ed Mullen became Morin’s financial adviser and, outside of the library, the closest thing he had to an adult friend. Their relationship began when Mullen, an insurance agent, was servicing a small life insurance policy of Morin’s. (His mother was the beneficiary.) Mullen noticed his client kept his earnings in a checking account and a few CDs. “He wasn’t very savvy with money,” Mullen says.

Mullen offered to help, and the two began meeting regularly—every year or two at first, then more frequently as they mixed some friendly lunches with their financial dealings. Morin started maxing out his retirement contributions (and UNH’s matching funds); he began diversifying his investments; he continued buying life insurance. Through all of this, Morin kept his mother as the beneficiary. But there was one important exception, Mullen says: an older, $100,000 life insurance policy that Morin took out in the late 1980s and designated to benefit the library.

Morin didn’t tell anyone he was becoming a multi-millionaire, and his lifestyle certainly didn’t offer any hints. He drove the sort of car you’d associate with a college student, not a college staffer. He wore the same clothes for decades, until a student worker took him to the mall for a shopping trip. (That same student persuaded him to attend a few of her family holidays.) The only major change came after his mother died in 2004. Morin decided to make UNH the beneficiary of his estate. Mullen asked his client several times if he wanted to alert the university to what was coming or to specify any uses for his donation—some scholarships for the library’s student workers, say. Morin would go home and think about it, but in the end he always declined. “I think I’ll just leave it as it is,” he told Mullen.

One day, in January 2014, Morin’s fellow librarians found him collapsed in his cubicle. The diagnosis was colon cancer, and while everyone was amazed by his resilience during surgery and then chemo, he never improved enough to return to work. Morin moved to Brookdale-Spruce Wood, an assisted-living facility near campus. The nurses fell for him quickly and noticed how much he liked to read. He was up to 1938 in his chronological quest.

Morin’s room at Brookdale included a working TV, among other amenities, and when football season kicked off in the fall of 2014 he started watching games for the first time. Mullen was shocked when he heard this—sports had never come up during their lunches. “I remember going to visit him and he’d be watching some obscure bowl game,” Mullen says, “Eastern Washington or Southern Illinois or whatever.” Morin never talked to his nurses about football. He didn’t follow any particular team. Instead, he immersed himself in the game’s components, in its systems and rules—and, yes, as UNH kept chanting after his death, in the names of its players and teams.

None of this made him a football fan. That was never how Morin’s passions worked. When Sky Gidge, the student journalist, asked Morin why he chose his reading regimen, he could offer only this answer: “Because I like the 1930s.” Morin couldn’t do much better when asked why he liked watching movies or even working at the library. In each case, it seemed mostly about focusing on a sprawling and complicated topic, about fixating on one thing and one thing only until he decided it was time to move on.

The University of New Hampshire made a mistake when it spent $1 million on a video scoreboard, and you’ll find echoes of that mistake on campuses all around the country. Let’s stick to scoreboards: In 2015, Auburn University debuted a high-definition video scoreboard of its own, a 190-foot-by-57-foot LED leviathan whose digital glow could be seen from 25 miles away. The project cost $13.9 million, but that wasn’t even the crazy part. Auburn’s new scoreboard was replacing another high-definition video scoreboard the school had installed only eight years before.

It’s not news that power-conference schools are making insane investments, especially in football, the sport with the fattest costs and fattest rewards, but the same thing is happening at smaller schools, where it’s arguably worse. At least Auburn brings big money in. Smaller schools don’t, which means they must quietly swindle their students. A couple years back, the Huffington Post and the Chronicle of Higher Education teamed up to analyze the “student athletic” fees charged by so many universities. They found that only 21 of the 201 Division I athletic departments they studied broke even or turned a profit. The other 180 depended on a staggering $10 billion in student fees and other subsidies to cover their ever-expanding athletic budgets.

UNH is a particularly egregious example. Jeff Smith, who teaches at the University of South Carolina-Upstate, crunches the numbers on athletic department subsidies. “[UNH] is easily in the highest 15 percent for subsidizing,” he says. The school exists in a state of perpetual budget crunch. (One reason is, well, its state: New Hampshire ranks dead last in spending per college student.) It charges one of the highest in-state tuition rates of any public four-year college. To keep its sports teams afloat, though, the school slaps one of those additional “student athletics” fees on every full-time undergrad. Multiply the fee—$1,075 for the current academic year—by the school’s 12,000 or so students and you’ve got a $13 million annual subsidy. And it’s not clear the students want big-time college sports; last year, even with the upgraded stadium and a good team, UNH couldn’t crack the FCS’s top 30 in attendance.

But none of this seems to matter. UNH’s administration has fetishized football, just like pretty much every other administration has fetishized football, and now even the meekest programs seem desperate to spend. When UNH was first considering a video scoreboard, back in 2014, the school’s architects dug up the price and construction details on a similar one from the University at Albany, one of the Wildcats’ Colonial Athletic Association conference mates. It cost $1 million. Never mind Auburn—UNH is trying to keep up with Albany, and that’s bad enough.

The University of New Hampshire also made a mistake in its handling of Robert Morin’s memory. The best place to see this isn’t the money; after all, Morin didn’t seem to care how the school spent it, mostly because he didn’t care about money at all. (More than one person can tell a story about discovering a drawer full of his uncashed checks.) Besides, UNH’s scoreboard—and its stadium, and so much else—was dumb no matter how it got funded, whether by unrestricted donations or slimy student fees. Money was never a good index of Robert Morin’s values, even if it seems to be an awfully good one of the values of university administrators.

Morin’s life suggests he cared far more about something else: respecting other people. While he worked hard at maintaining his privacy, he still acted decently and kindly toward co-workers, students, and strangers. Even those who knew him only briefly saw this. “We really enjoyed him while he was here,” says an employee at Brookdale, the assisted-living facility. “He was a very sweet man.”

It was on measures like this that UNH cheated Morin by treating him less like a human being than a marketing prop. This treatment had started early, of course, during those initial PR huddles, and it only got worse once a real backlash to the scoreboard emerged. The outrage peaked around September 10, 2016, the date of UNH’s first game at the new stadium. Instead of whistling at the scoreboard, alumni were writing angry blog posts. New Hampshire’s Speaker of the House was lobbing zingers—“UNH is spending $1 million to tell us what the score is”—though he might have had a stronger case if he and his colleagues did more to support higher education.

At first, UNH responded with its previous routine. Huddleston, the university president, invoked Morin’s fandom in an email to the trustees: “Mr. Morin was an avid football fan. . . . [T]his use was certainly consistent with one of his major demonstrated interests.” Dutton, the UNH Foundation president, repeated the fan link in an interview—and then, in what was surely the low point in the whole affair, suggested that Morin’s old insurance policy, the $100,000 outlier that had specified the library, was actually evidence that he wouldn’t have wanted his colleagues to receive any extra cash. “We felt like he was clear,” Dutton said. “$100,000 for the library.”

It was one last attempt to bend Morin’s quirks until they matched the university’s preexisting priorities, to jam a generous man’s life into a campus master plan. But before long something shifted. The university seemed to realize that their feel-good story had soured, and on September 20 UNH media relations sent out a new set of talking points. They encouraged staffers to note that the scoreboard was an “important investment,” that the stadium would host the Special Olympics, that UNH actually had its own history of frugality. What the talking points didn’t mention was Morin’s interest in football. In fact, they barely mentioned him. The librarian had given his university a fortune, then failed to give it some good news. Now that both transactions were complete, he didn’t seem to matter at all.