The funniest man working for ESPN is most famous for a line that wasn't funny at all. Is that the punchline here? Nobody in newspapering over the past few decades has delivered as many morning-coffee-through-the-nose laugh lines as Norman Chad has in his media and football-betting columns. An unsentimental smart-ass who has, alongside the jokes about failed marriages, kept up a mordant critique of corporatized sports and sports media, he is part of an honorable lineage of waggish sportswriters that runs back through Dan Jenkins and John Lardner. Back when he and alleged funnyman Tony Kornheiser worked at the Washington Post together, it was Kornheiser who, as deadline approached, would occasionally rely on Chad for jokes, not the other way around.

And yet if you know him at all, you probably know Chad for something he said on TV in 2003—something that was almost, yes, sentimental.

"This is beyond fairy tale," he said. "It's inconceivable!"

He was talking about poker. Specifically, he was, in his capacity as the color commentator for the ESPN broadcast of the World Series of Poker, delivering the final verdict on the improbable run of Chris Moneymaker, a 27-year-old accountant from Tennessee who had earned a spot in the WSOP by winning an online tournament sponsored by the internet gambling outfit PokerStars. That qualifying event had a $39 buy-in, which Moneymaker ultimately parlayed into the $2.5 million first prize. Chad's line immediately became poker's "Do you believe in miracles?" and as the sport enjoyed its boom, Norman Chad enjoyed a smaller one of his own.

"Norman Chad doesn't get enough credit," says Matt Maranz, who produced ESPN's WSOP programming from its 2003 debut through 2010, explaining what sparked the golden age of American poker. "Without him, there is no boom."

The poker boom went bust a few years ago, for reasons having nothing to do with Chad running out of lines about ex-wives or players' table attire or Sam Wyche, but lots to do with oddball internet gaming regulations and puritanism. Yet Chad and ESPN remain in the game. On Monday, Bristol began beaming out the WSOP's final table broadcasts from the Rio in Las Vegas, with coverage concluding tonight, and Chad was once again observing the action alongside longtime partner Lon McEachern and looking for giggle room.

Maybe that's the better punchline: The anti-corporate iconoclast with all the jokes about failed marriages has found a happy one with the unlikeliest of partners, ESPN.

Chad's body of work shows his sense of humor is at least as developed as, say, a Yankee fan's sense of entitlement. That makes it pretty rich that he enjoys talking about a time when he lost the ability to make anybody even crack a smile.

"My biggest professional disappointment is how bad I was as a standup comic," says Chad, 56. "I couldn't make anybody laugh."

Yes, his career low points came in front of live crowds. Chad was fresh out of college, copy-editing stories written by a powerhouse lineup of writers at the Washington Post's sports section during the week and chasing a dream at open mics at D.C. nightclubs come the weekends. He performed for tips and laughs and never got much of either. He can't recall any part of his routine that worked, and he promises he hasn't blacked out his good material, because there wasn't any. He says he tried to stay away from "dick jokes and mother-in-law jokes" and standard comic fare, and he didn't yet have any ex-wives to serve as comic props—the woman who would become Chad's first ex-wife, in fact, even helped him set up stages at the open mics he emceed. With masochistic glee he recites his go-to closing gag: "an imitation of a Siberian Husky smoking weed." He kept the stoner-dog bit in his routine long after realizing it always got the crowd to impersonate a field of crickets. His most memorable moment in those three humbling years alone on a stage came when somebody threw an egg at him, and somehow got away, unapprehended.

"I always figured [the egg thrower] was a friend who thought it would help my show," he says. "I was bombing. But who brings an egg to a club? That was an early sign I should get out of that business."

And so he did. But the world's been a funnier place ever since Chad ditched stand-up and took a seat behind a keyboard. He grew up wanting to be a journalist, and he got off to a good start in the field while attending the University of Maryland. He'd risen to editor-in-chief of the school newspaper, The Diamondback, when he was just a sophomore. But Chad's quick rise, it turns out, was more a sign that the paper was imploding than a token of his abilities. The now-defunct D.C. daily, The Washington Star, wrote up The Diamondback's dysfunction, explaining that Chad was the fourth editor that semester alone. One kid was editor "for one edition" before Chad was tapped. Surely it augured something for Chad's career that The Star's story ran adjacent to a piece titled, "Canned Hams Recalled."

After his stint atop The Diamondback, he was hired by the Washington Post. He occupied a spot on the paper's bottom rung during a time when the sports section was loaded with current and future stars—John Feinstein, Tony Kornheiser, Michael Wilbon, Thomas Boswell, and Dave Kindred, among others. (One sign of the talent glut: Current New Yorker editor David Remnick was tasked to cover the USFL's Washington Federals.) Section editor George Solomon never gave Chad any indication he'd ever leapfrog any of them.

Solomon did, however, give Chad his first good writing gig, as the sports media critic for the Post's "Sports Waves" column in 1984.

That role was in his blood. The archives of The Washington Star contain a letter to the editor that appeared in July 1973 in which a Norman Chad from Silver Spring got pissy with curmudgeonly columnist and local legend Morris Siegel. It seems Siegel had taken a small shot in print at Warner Wolf, the pioneering TV sportscaster whose emphasis on videotaped highlights in the early 1970s changed the way sports were reported on local news broadcasts everywhere. "Warner's excellence on the tube is as clear as Siegel's inability at his job," young Norman wrote. "Grow up, Mo."

At the Post, Chad was a harsher critic of sports media than he'd been as a teen. He was decades ahead of his peers in bashing the crap out of Tim McCarver, who was at the peak of his color commentating renown in 1986 when Chad called him "the most overrated" analyst in network sports. "He can do 10 minutes on the way a grounder hops," Chad wrote. "McCarver creates things to analyze, much the same way an auto mechanic might find unnecessary repairs to give himself more work and income. To McCarver, the hands on a clock don't just move; he'd probably tell us that 'they posit themselves into such an area so as to correctly indicate the time at that given moment.'"

But while the critic's column raised his Q rating around D.C., Solomon kept Chad on the copy desk. After a while it became clear that he was never going to get off it. So he jumped when Frank Deford recruited him for The National, the short-lived but much-beloved sports daily that debuted in 1990 with an all-star lineup of writing talent and the expectation that it would revolutionize sports reporting. When Grantland did an oral history of The National's brief run, Deford, paper's editor-in-chief, belatedly thanked the Post for not recognizing or exploiting Chad's obvious gifts.

"We got Norman Chad off the rewrite desk at the Washington Post," Deford said. "There wasn't a chance for Norman to be himself there. George Solomon, great editor—but what the hell was he thinking?"

Deford turned Chad loose on the biggest names in sports media, though not always the biggest people. As outlined in the Grantland retrospective, Chad at one point called Bob Costas "the 5-foot, 5-inch Bob Costas," only to have Costas's people complain that he was actually 5-foot-8. So Chad began referring to him as "Bob Costas, who was not 5-feet, 5-inches tall."

Chad sold his bosses at The National on his idea for a football-betting column that showed little respect for football or betting. He figured all the touts who picked games each week every football season were full of crap, and he set out to prove it. "I went to my editors and said, 'I bet I could do just as well as anybody flipping a coin,'" Chad told me in 1999.

So each week he'd get a list of games and point spreads, then determine his picks by flipping a 1984 Philadelphia-minted half-dollar for each one. He'd then list his selections alongside a quip that made up for what it lacked in actual football intelligence with utter disdain for Sam Wyche or the institution of marriage.

But then something funny happened: Chad's picks came in. Week after week, year after year. So while The National folded after just a year and a half on the newsstands, Chad kept doing the betting column, first for the Washington Post, then in syndication.

From a Redskins-Ravens game in 1997: "Mayor Marion Barry snaps to attention when the Redskins come with the dime package. Pick: Redskins." Redskins-Cardinals, 1998: "Redskins defensive tackle Dana Stubblefield injured his other knee Tuesday jumping to a conclusion. Pick: Cardinals." Cowboys-Cardinals, same year: "So Deion's found God. Geez, I didn't even know he was looking. Pick: Cardinals." From Cowboys-Steelers, 1999: "Cowboys just announced new Tuesday routine: game film in morning, surveillance video in afternoon .... Pick: Steelers." Giants-Jaguars, 1997: "After throwing seven passes in his first two NFL seasons, Rob Johnson was 20-of-24 for 294 yards Sunday, reminiscent of Burt Reynolds, who barely spoke a line for three seasons on Gunsmoke before starring in Dan August. Pick: Jaguars."

He calls the picks column his "finest work." When he gave it up after 12 years, he'd come out ahead every year but two, including a nine-year streak with a winning record that ended, he says, when "the coin I was flipping finally went into a slump." Chad had never followed the betting advice he'd given to readers. "I don't bet on sports," he says. "You can't beat the house betting on sports."

When The National folded, Chad moved that picks column to syndication and accepted an offer to cover media for Sports Illustrated. That allowed him to move to Los Angeles, where he wanted to give sitcom writing a try. But other than the relocation, nothing about the SI gig went according to plan. Everything, in fact, started to go south as soon as he went west, when the editor who'd hired him got canned. The new regime, he says, hated his style and never failed to let him know it.

"They just stopped running my stuff," he says. "I'd turn a column in every Sunday, and then it wouldn't run. I think I turned in 26 columns in a year, and 16 of them ran. Now, 16 for 26 might be an OK percentage for a pro quarterback, but not a columnist."

He didn't come back to SI for a second year. Instead, he supplemented the income from the syndicated picks column by publishing a book in 1993, called Hold On, Honey, I'll Take You to the Hospital at Halftime (Confessions of a TV Sports Junkie), that was both a memoir and a compendium of his sports media columns. Chad was as rough on his former employer as he was on McCarver. SI at the time was the king of the sports media heap, and Chad accused the magazine of thinking "advertiser first" in every situation.

He wrote about an incident in which a column of his was killed because he'd made fun of Chris Berman. "Why not?" he wrote in the book. "ESPN advertises weekly." Sponsors were so coddled at SI, Chad alleged, that he wasn't allowed to say in his company bio that he liked Rolling Rock beer because "higher ups" at the magazine wanted only Anheuser-Busch beverages named. He declined to rewrite the bio, so it was done for him: "His current likes run from poker to Rolling Rock" had been edited to "His current likes run from poker to the beers of Latrobe, Pa."

"Herein lies a key problem to the Sports Illustrated of the nineties: It is firmly part of the institutional, corporate nature of big-money sports," Chad wrote. "Heck, SI's in bed with so many people, the magazine is converting offices into guest rooms."

In 2001, after pulling the plug on the picks column, Chad took up where the book had left off, dubbing himself "The Couch Slouch" and getting back into media criticism with a weekly column for AOL, which he then took to syndication. Like "Sports Waves" at the Post, Chad's AOL column was often a display of precision knifework. In 2009, he took on CBS college basketball commentator Clark Kellogg and his annual McCarvering of March Madness:

For Kellogg, the shortest distance between two points is a circumlocutious statement. He favors multisyllabic words, like "perimeter" and "interior" and "circumlocutious"; heck, he's got to love "multisyllabic" because, well, it's multisyllabic.

In short, Kellogg butchers English, obfuscates the obvious and makes simple points seem elaborate — all for our entertainment value! Frankly, he might call himself a "mangled linguistic savant."

Here now are excerpts from, as Kellogg would say, his "body of work." All of the words between quotations are Kellogg's, unexpurgated; all the words after are mine, unenthralled:

"Duke has done a masterful job of controlling pace and tempo." "Pace and tempo" always go together, you know, like "Tango & Cash."

[...]

"The speed and length of LSU has really caught Butler off-guard." LSU is faster and taller than Butler.

"He gets a little pseudo-penetration." It's the illusion of penetration.

"They've got to turn that turnover funnel off." In my house, that's next to the circuit breakers.

[...]

"At this point of the season, it's more about execution than about experience." For me, it's more about the mute button.

"We call that 'rim-running' in basketball jargon." Oh, I didn't realize he ever used jargon.

He kept hammering away at the bigwigs, too. During a fairly positive critique of NBC's Sunday night NFL coverage, Chad blasted the network for "foisting" SI's Peter King on viewers as a football "insider," saying King "hasn't had a big scoop since he was at Baskin Robbins." (The Washington Post's editors cut that line from the version of the "Couch Slouch" column that ran in the slouch's former paper.) In that same column, Chad disclosed to readers that at that point in his career, the poker broadcasts left him conflicted out the wazoo for a media critic: "Dear ESPN," he wrote. "I'm on the payroll—you guys are great!!!"

He's been in bed with ESPN since 2003, when the network got into the poker business.

The criticisms Chad had leveled at SI some 20 years ago sound a heckuva lot like what latter-day media critics lob at ESPN, which became the unrivaled giant in sports media shortly after Chad got out of the criticism biz.

Mark Shapiro was vice president for programming and production at the time. He upped the ante on Bristol's poker coverage. Shapiro was behind some of the network's greatest ratings successes—Pardon the Interruption and Around the Horn among them—yet also stands as one of the most polarizing figures in its history. He contracted a New Jersey firm, 441 Productions, to put on that year's World Series of Poker. Neither of 441's co-founders, Matt Maranz and Dave Swartz, had a sports or poker background. Documentaries were their bailiwick.

Maranz admits he and Schwarz were flying blind. "There was no blueprint for what we did," he says. "There was no sport that was covered the way we could cover poker. We couldn't watch the NFL and steal from that. We were starting from scratch."

Shapiro, who had become friendly with Chad from other projects, hooked him up with the 441 honchos and asked him to bring them up to speed on card playing.

"I was the only compulsive gambler Mark knew," says Chad.

They had some avant-garde ideas on how to make poker more watchable. Though five- and seven-card stud were more popular in basement poker games, no-limit Texas Hold 'Em was the game chosen for the big telecasts. It allowed the producers to plant mini-cameras in the table that would show the viewing audience each player's "hole cards"—the two cards dealt facedown to each player. No American audience had ever seen poker from that perspective.

"The viewers at home know more than the players they're watching on TV," he says. "That means you know a guy's going to lose all his money before he does. That's very important."

From discussions with Chad, Maranz decided that they'd focus more on a player's personality than on the technical elements of the game.

"When you break it down, poker is nine guys sitting at a table staring at each other," Maranz says. "It's not real exciting. The strategy's interesting, but you can't see inside the players' minds. So the idea was to have fun. We're going to talk about the players, and have fun with that."

Maranz was already a big fan of Chad from his days at The National and from his syndicated football columns. Shortly after they met, Maranz became convinced that his team needed more than ideas from Chad; they wanted him to work the telecasts. But when he called Chad to hire him as a commentator, Chad was characteristically oblivious.

"Norman couldn't tell I was offering him a job," says Maranz. "So I'm saying, 'It would really be great if we had somebody who knew poker, somebody who also knew television, somebody who had a sense of humor ...' I'm going on and on and all I'm hearing from him is, 'Yeah, yeah, if only you could find that guy.' Finally, I had to say, 'Norman, would you want to fucking do this?'"

Chad took the job. He now says he went into ESPN's first year of WSOP broadcasts thinking he'd borrow from Mystery Science Theater 3000, the cult show in which a panel of oddball hosts cracked wise while watching bad cinema; Maranz, in turn, says he'd envisioned Chad becoming the "Howard Cosell of poker." The fledgling production team was gifted the storybook tale of Chris Moneymaker, leading to Chad's famous line, and soon enough Chad had the respect of the pros. He knew he'd penetrated their ranks when Phil Hellmuth, the 1989 WSOP main event winner and among the most successful and popular players of all time—and a man with all the personality of a Hollywood agent's answering machine—ascribed his reputation as the "bad boy" of poker to the WSOP commentator's on-air remarks about him. "The guy [Chad] has probably made me $10 million," Hellmuth told Bluff, a magazine for hardcores, "all while turning me into the bad boy of poker—and I love being poker's bad boy."

"I compared him to the bad boy of tennis, John McEnroe, and bowling's Pete Weber," Chad says. "I cast him in the black hat early."

Chad downplays his part in the mainstreaming of poker. He attributes the boom to the storytelling abilities of Maranz and Schwarz. In an interview with Bluff, Chad said "Pee Wee Herman, Pat Paulsen, or Kato Kaelin" could have taken his place on the 2003 telecasts and the game would have gotten just as big.

"I'm just a passenger in the getaway car," he said.

But Maranz says Chad was a vital component to the success of the event. "There were a lot of components to this 'perfect storm' for poker in 2003," he says. "Being on television, having internet poker growing, having Chris Moneymaker win at that time, take away any one of those and it wouldn't have been the same. And I think Norman's right there with them."

In any case, the boom was on. In that first year of ESPN's WSOP, Moneymaker topped a field of 839 players; just one year later, the same tournament attracted 2,576 entrants going for a $5 million top prize.

And by 2006, there were 8,773 players chasing a $12 million payday.

Then came the bust. The feds started peeing on poker's parade in October 2006, when President George W. Bush signed the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA), which banned financial institutions from handling most online gambling transactions with U.S. residents. Fantasy sports were specifically exempted, and horse racing was exempted from the regulations that grew out of the vaguely written statute. But the biggest upshot was that Joe Blow could no longer play poker at his computer with real money at stake. The impact on the WSOP's Main Event was immediate and devastating: 6,358 players entered the 2007 WSOP, or 2,415 fewer than had the previous year, stopping a growth streak that reached back to 1992.

A few poker companies cited the lack of clarity in UIGEA's language while continuing to offer online accounts to U.S. bettors. But the feds quashed the holdouts big time: On April 15, 2011, the founders of online gambling outfits that took U.S. accounts—PokerStars, Full Tilt Poker, and Absolute Poker—were indicted en masse for UIGEA violations. (It didn't help that Full Tilt had misused players' funds so egregiously that it was functionally a ponzi scheme.) That day became known in gambling circles as Black Friday. Since then, the online poker industry has shown signs of a reawakening. Three states (Nevada, New Jersey, and Delaware) have passed laws that allow their citizens to play online poker. But John Pappas, executive director of the D.C.-based advocacy group Poker Players Alliance, says he's not hopeful anything will happen on the federal level to restore the right to his favorite form of online gaming anytime soon. "We've fought this for a number of years now," Pappas says, "but we're dealing with a Congress that's incapable of passing anything." Pappas group is funded mainly by PokerStars, which, because of the U.S.'s government's unfriendliness toward online poker firms, is headquartered in the Isle of Man.

Pappas's main foe is Sheldon Adelson, the hyper-conservative multi-billionaire and casino owner, who last year told Forbes he'd "spend whatever it takes" to increase prohibitions on online gambling.

Dan Ochs, director of programming and acquisitions at ESPN, says the network is "pretty happy" with the ratings for the network's poker broadcasts in the post-boom era.

"The last three years we've been flat, which is a decent story for us," says Ochs.

Even in its wounded state, World Series of Poker telecasts on ESPN still attract more viewers than WNBA, MLS, or NHL games.

Ochs says the network is buoyed by last year's final table broadcasts, which drew 1.2 million viewers, an audience 50 percent larger than the one that watched 2012's show. Ochs attributes that increase to a format tweak—for the first time, the first night's broadcast continued until there were just two players left, instead of the traditional three—as well as dumb luck. "That set up a head-to-head matchup with two entertaining guys," Ochs says, referring to Jay Farber, a colorful Vegas nightclub host, and Ryan Riess, who wore a Calvin Johnson jersey all the way to winning the top prize of $8,361,570.

The field of 6,683, which was culled down to the final nine players in July, did its part to deliver at least one very interesting storyline heading into this week's prime-time telecasts: Southern California-based Mark Newhouse, a favorite among pros, made the final table for the second year in a row. One number cruncher put the odds of his reaching consecutive finals at 524,558-1.

The ESPN cast is calling the action from a booth on location at the Rio in Las Vegas. WSOP telecasts other than the final table are on tape. In fact, for the preliminary rounds of this year's event, Chad didn't even need to be on site while the cards were being dealt. No matter where those events were held, the voiceover for ESPN telecasts was added at a later date in New York or Los Angeles studios. He and McEachern get to view the action before adding commentary, meaning Chad's witticisms needn't be spontaneous; they just needed to sound spontaneous. While working a 2005 tournament, McEachern dropped in a Kenny Rogers line about how important it was to "know when to walk away, and know when to run." Chad's response: "You know, Lon, my first ex-wife walked away. My second ex-wife ran." Was it scripted or off-the-cuff? Only Chad knows.

In any case, scripting won't fly this week. This year's WSOP final table is being marketed as a live broadcast, and for Chad and the others calling the action some 30 yards from the table, as well as for the audience at home, the event indeed appears to be live. Yet in reality, ESPN's on-air crew doesn't see the action until 30 minutes after it happens. The delay is strictly for security reasons. For the first time at a WSOP final table, viewers get to see the hole cards while they see the hand being played, an advent that all involved describe as a huge boon to the broadcasts. But showing hole cards during play creates a whole new dilemma. A top prize of $10 million is up for grabs this year, and producers feel the integrity of the event would suffer a mortal wound if insider info somehow found its way to a player at the table. So only a handful of people will have access to the hole-card camera feed, and those folks will be locked away in a production trailer with armed guards outside.

Still, every gag coming out of Chad's mouth goes out to a million households and change as soon as he delivers it. He gets no chance to preview the action. No mulligans, either. For a guy who after several decades as a standup bomb still dwells on those nights when he last worked this live and tells anybody who'll listen of all those nights that he couldn't make a couple dozen people laugh, it would seem as if the pressure is on. But Chad's not worried he'll come away with egg on his face this time.

"I'm better at my job now than I was then," he says.

He's not joking.

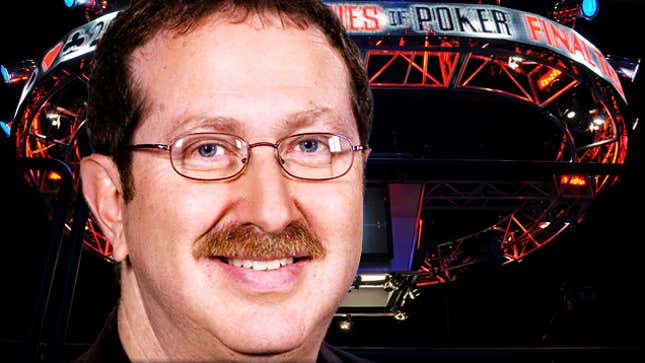

Image by Jim Cooke