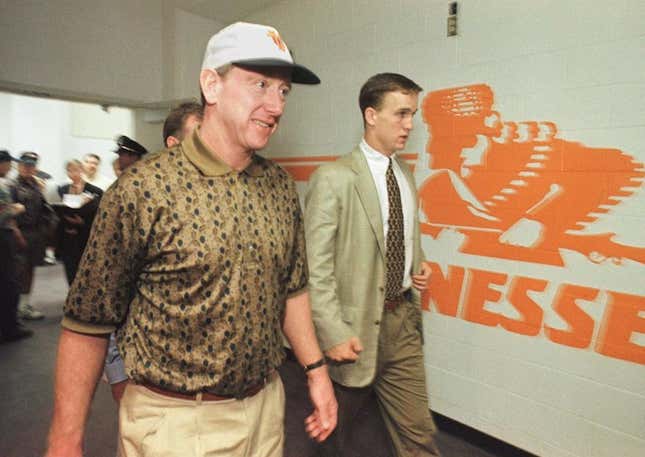

Twenty years ago, the NFL draft was marked by one of the most fateful quarterback choices in league history: Peyton Manning’s decision to stay at the University of Tennessee for his senior year. The Jets, who had the No. 1 pick in 1997, are still reeling from the aftershocks. And it all may have been because Bill Parcells couldn’t commit to what practically everyone else thought was a sure thing.

Manning’s prolific NFL career can be summed up thusly: He’s one of the greatest passers in history. The end. But what set Manning apart as far back as his college days was his status as a fail-safe prospect, a franchise savior. His 17-year career with the Colts and Broncos played out largely the way most observers and fans anticipated it would. But then, as now, quarterbacks were a scarce commodity. Then, as now, front offices thirsty for quarterbacks would panic themselves into believing any old chump at the top of the prospect heap could be molded into Joe Montana or Tom Brady. But Peyton Manning was different. He was that rarest of gems. He had that generational pedigree.

Now consider what could have been had he elected to declare for the draft after his junior season at Tennessee: The Jets, whose franchise history has more or less been a fruitless 40-year search for Joe Namath’s replacement, were up first. In the spring of ’97, the Jets were coming off a 1-15 nightmare that had shoved head coach Rich Kotite into permanent exile somewhere on Staten Island. But they had just hired Bill Parcells, whose handiwork to date included swift, massive construction projects with both the Giants and Patriots. Parcells had just taken the Pats to the Super Bowl, and the Jets had to compensate the Patriots for taking him away. There was some jousting, but in the end that compensation did not include the No. 1 pick in the draft. A Manning-Parcells pairing seemed to be inevitable.

If only it had been that simple.

David Cutcliffe told me he was “convinced” Manning would leave for the NFL after Manning’s junior season. Now the head coach at Duke, Cutcliffe was Manning’s offensive coordinator at Tennessee. He was so sure Manning was a goner that he had begun making preparations for a complete re-do of the Volunteers’ offense.

On the night before Manning held a press conference to announce his decision, Cutcliffe said he was in Atlanta with a few other coaches to meet with Dan Reeves, then the head coach of the Falcons. Cutcliffe was there learn a few new offensive concepts from Reeves. But then the phone at his hotel rang around 1 a.m. It was Manning calling. Cutcliffe described Manning as a “practical joker” who gave off every indication he would be leaving school. So Cutcliffe initially wasn’t sure whether to believe him when Manning said he was staying. Manning soon let him know this was no gag.

“We went back to Knoxville right then,” Cutcliffe told me.

Rich Cimini has covered the Jets—without hazard pay—since 1985, first with Newsday, then with the New York Daily News, now with ESPN.com. He was at the Daily News at the time of Manning’s decision, and he wrote a story the morning of Manning’s press-conference announcement that said Manning was staying in school. Cimini got the info from what he thought was a rock-solid source. But, as Cimini wrote last year:

My heart sank when I got off the plane in Knoxville and saw the front page of the local paper. It screamed with the headline that none of its readership wanted to see: Their favorite son was leaning toward the NFL.

I feared an embarrassing faux pas. My story was wrong; surely, the locals had the inside scoop.

The headline Cimini saw splashed across page Page A-1 of the Knoxville News-Sentinel on March 5, 1997, read: “Manning’s moment; Grid decision: Insiders expect him to go pro.” But the actual story was more nuanced; it cited separate sources saying two different things. As Cutcliffe’s story demonstrates, it was clear Manning had kept his true feelings close to the vest. Manning even set up his announcement by delivering what Cimini described as “a 30-second preamble in which he made it sound like he was leaving school” before he finally said he was staying. Manning’s stated rationale was that he only got to be a college kid once, and he wanted to milk the experience for all it was worth—a not unreasonable stance, even for a guy who risked sacrificing millions in the event of a catastrophic injury.

“I’m having an incredible experience as a student-athlete at Tennessee,’’ Manning said that day. “But if I’m good enough to play in the NFL, as many experts say I am, then I can only be better after one more season.”

As obvious as it seems now, in hindsight, that Parcells was going to take Manning and place the Jets on a path to prosperity, Parcells never articulated his intentions to Manning’s camp—and that reticence may have influenced Manning into staying.

Because Manning had not declared for the draft, NFL teams were prohibited from having contact with him. There was nothing, of course, to stop Parcells from talking to Manning’s father, Archie, a former NFL quarterback, or to keep Parcells from denying any such contact took place. In an interview last year with Gary Myers of the New York Daily News, Parcells even said the league office was watching the Jets “like hawks” for any possible tampering with Manning.

But just before the draft, a few weeks after Manning announced he was staying in school, his mother, Olivia, told the New York Times:

“I think Peyton kept waiting for something to hit him, and when it didn’t happen, he wanted to return to school.”

She said that no one from the Jets made direct or indirect overtures.

“Peyton wanted to get it all done by April 4, when college practice started,” she said when asked whether the Jets might have been able to get him if they had tried. “He kept waiting.”

Myers reported that Archie had even called Parcells twice prior to Manning’s announcement—at Peyton’s request. More Myers:

He wanted to play for Parcells, he wanted to play for the Jets, he wanted to play in New York, but he didn’t want to declare for the draft and then be concerned that Parcells would trade the pick.

[...]

Archie told Parcells he thought there was a good chance Peyton would stay in school. That was an adjustment in Manning’s thinking because throughout his junior year he later said he was pretty intent on leaving. Around the NFL at the time, the consensus seemed to be if Parcells committed to Manning, he would leave Tennessee.

“I’m telling you, he’s pretty torn,” Archie told Parcells.

Parcells didn’t tell Archie his plan.

“If Bill had come out and said, ‘Peyton, you’re my guy, I’m going to pick you,’ it may have made it a little bit harder,” Archie said. “But I swear he wanted to be a senior.”

That last part squares with what Cutcliffe told me. Manning, according to Cutcliffe, had consulted with future NBA star Tim Duncan before making his decision. A year earlier, Duncan had chosen to stay for his senior year at Wake Forest rather than declare early for the NBA draft. “Peyton’s an unusual individual,” Cutcliffe said. “He kept saying he only had one chance to be a senior. It was all true.”

One matter Cutcliffe insisted did not influence Manning’s decision was the sexual harassment and employment discrimination lawsuit against the University of Tennessee that had been filed in the summer of 1996 by one of the school’s athletic trainers. Manning was among the athletes accused in the case, for which the trainer was paid a settlement in August 1997. The trainer later sued Manning for defamation, a case that ended in 2003 with an undisclosed settlement.

Parcells, for his part, told Myers he “knew” Manning would stay in school. And in a conversation three years ago with Cimini, Parcells hedged a bit more:

The Hall of Fame coach hasn’t revealed too much over the years about that chapter—some believe he would’ve traded the pick to accumulate extra draft choices—but he strongly hinted he would’ve selected Manning.

“Obviously, we had an interest in a quarterback, so, had he been available, I’m certain he would’ve been very, very strongly in the mix,” said Parcells, claiming he always had a “gut feeling” that Manning would stay at Tennessee.

Why might Parcells have been hesitant about picking Manning, given Manning’s bona fides? The Jets’ quarterback at the time was Neil O’Donnell, who was just two years removed from a Super Bowl appearance with the Steelers. Parcells also might have been tempted to trade down for additional picks because of how barren the Jets’ roster was. After Manning decided to stay in school, Parcells wound up trading down twice. The Rams ended up with the No. 1 pick and selected offensive tackle Orlando Pace, a future Hall of Famer. The Jets, at No. 8, picked linebacker James Farrior, whose rather solid career was spent mostly with the Steelers.

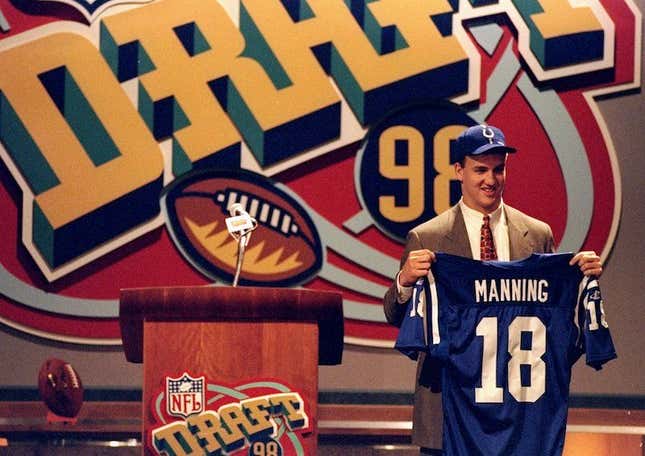

Manning returned to Tennessee and threw for 3,819 yards and 36 touchdowns as a senior. He was the SEC player of the year and a runner-up for the Heisman Trophy. The Vols finished 11-2 and ranked seventh in the final AP poll, and Manning’s status as the prize of the draft was not affected by a blowout loss to co-national champion Nebraska in the Orange Bowl. The Colts drafted him No. 1 overall in 1998.

As it turned out, the ’97 Jets improved to 9-7, with O’Donnell making 14 starts. But they lost three of their last four and missed the playoffs. And O’Donnell wound up in Parcells’s dog house. In June 1998, Parcells cut O’Donnell after he refused to rework his contract. Vinny Testaverde, then 34 years old, was signed on as a replacement soon afterward and guided the Jets to the 1998 AFC Championship Game.

The Jets were a popular preseason Super Bowl pick in ’99 (seriously), but that optimism evaporated when Testaverde tore his Achilles in Week 1. Parcells quit after that season, and Bill Belichick lasted one day as his “HC of the NYJ” replacement before resigning abruptly to torture the Jets (and the rest of the NFL) from New England. Chad Pennington, Brett Favre, and Mark Sanchez provided the Jets with some fleeting rays of sunshine in the years that followed, but Jets quarterbacks in this century have mostly been shadowed by black clouds. The same Colts that drafted Manning, meanwhile, had Andrew Luck—another sure-thing quarterback—fall into their laps when again they had the No. 1 pick in 2012. An aging Manning finished out his career in 2015 by winning the Super Bowl—his second—with the Broncos.

There’s no telling what might have actually happened had Manning jumped to the NFL a year early, but it’s difficult not to imagine some kind of bright future for the Jets. The piercing reality is the Jets are tied with the Broncos and 49ers for most quarterbacks drafted (11) since 1999, though unlike the Broncos and 49ers, they haven’t made the Super Bowl in all that time. The Jets are forever mentoring quarterbacks. And after not drafting one last week, they are about to enter 2017 with Josh McCown, Bryce Petty, and Christian Hackenberg as their passing options. How’s that for scarcity?