New York Giants defensive end Jason Pierre-Paul is scheduled to face off against ESPN and reporter Adam Schefter in a Florida federal court next August. At issue is a tweet Schefter posted in 2015 containing two photos of Pierre-Paul’s medical records.

Pierre-Paul claims that ESPN violated his privacy by publishing the photos; ESPN asserts that the publication was protected by the First Amendment. ESPN had the case transferred from state to federal court and attempted to have it dismissed, but the judge allowed Pierre-Paul’s claims of invasion of privacy to proceed.

This case bears a number of similarities to the Hulk Hogan invasion-of-privacy lawsuit, funded by Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, that led to a $140 million judgment against Gawker Media, the soon-to-be-former owner of the website you are currently reading. That was a state case and Pierre-Paul’s is federal, but both are lawsuits brought in Florida by a public figure against a media organization for publishing visual evidence that a story was true. ESPN is even using the same law firm, Levine Sullivan Koch & Schulz, as Gawker Media. (Given that you’re reading this, you probably know about and have your own opinion on the Hogan case; given that I work here, you probably know mine, and thus can adjust the number of grains of salt with which you read the rest of this piece accordingly.)

It’s likely that ESPN is highly interested in settling with Pierre-Paul without going to trial. But even if that happens, the lawsuit has already had an enormous impact on media organizations, and you don’t have to care at all about Schefter or ESPN to understand why.

Between technological disruption, cratering public confidence in its work, thin-skinned billionaires attempting to put publishers out of business, and a major-party presidential candidate who wants to make it easier to sue news organizations, the press is in retreat and under attack in a way that it hasn’t been for decades. Now, as the powerful seek to operate unchecked, the courts are opening up the question of whether it’s even legal to publish true things about public figures.

On July 4, 2015, Jason Pierre-Paul severely injured his hand in a fireworks accident. Over the next day NFL reporters advanced the story, reporting that the accident had happened, that Pierre-Paul had been hospitalized, that his hand was injured, and that he’d burned his palm and fingers. At that point the flow of information ceased; for three days there were no substantive updates on Pierre-Paul’s condition, as even Giants officials who traveled to Miami to see the free agent in the hospital were turned away.

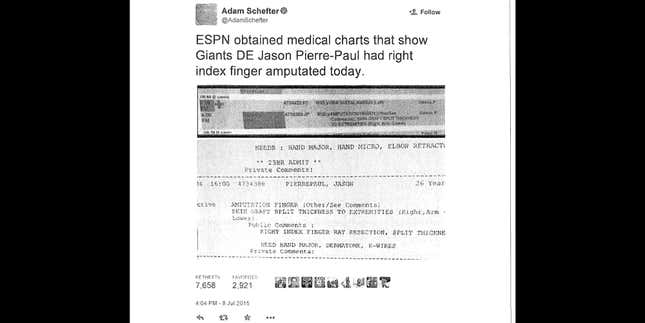

That information drought ended on July 8, when Schefter reported that Pierre-Paul’s right index finger had been amputated, and posted photos of hospital records to prove it.

Everybody agrees that Pierre-Paul is a public figure, and that Schefter had a right to report on his condition. What Pierre-Paul takes issue with is the publication of photographs of his hospital charts—“while the amputation may have been of legitimate public concern, the Chart itself was not,” he argued in his initial legal filing.

Unsurprisingly, ESPN’s motion to dismiss ridicules this idea (emphasis mine):

Plaintiff’s lawsuit proceeds on the theory that while it was legitimate for Mr. Schefter to report the details of Plaintiff’s medical treatment in the form of words contained in a news report, it was unlawful for him to definitively corroborate his reporting by also providing two photos of a small portion of a page of hospital records that contained essentially the same words. Put another way, Plaintiff’s theory is that it is fine to quote from a document, but it is unlawful to attach a photo of similar words as they appear in the document. That proposition is meritless, as a matter of both law and common sense.

One of the photos appears to be a printout of a hospital record, while the other appears to be of the hospital’s electronic health record system. Besides the specific details of the procedures Pierre-Paul underwent—which he concedes Schefter can report on—all that is displayed is hospital administrative information: the time of surgery, the names of the surgeons, the file’s record number.

Pierre-Paul will undoubtedly make a more specific claim at trial about how the disclosure of this information violated his privacy, but for the time being he simply claims that it caused unspecified damages greater than $75,000, and that the release was “highly offensive to a reasonable person of ordinary sensibilities.”

Pierre-Paul’s suit also asserted that by obtaining and posting the photos, Schefter had violated Florida’s medical-privacy statute. The judge dismissed that claim, ruling that the law doesn’t apply to third parties like Schefter. (Separately, Miami’s Jackson Memorial Hospital, where Pierre-Paul was treated, fired two employees for “inappropriately” accessing his medical record. The hospital also says that “related litigation” has been settled, while one of the fired employees is suing Jackson Memorial, arguing that she didn’t access Pierre-Paul’s medical record.)

There is an important distinction, often blurred, between questions of journalistic ethics and of legality. The question of whether Schefter should have posted the photos, this is to say, is different from the question of whether he was legally allowed to.

In an interview with Sports Illustrated that Pierre-Paul cited in his filing, Schefter said that “in hindsight I could and should have done even more here due to the sensitivity of the situation.” But he also defended his reporting, saying that “in a day and age in which pictures and videos tell stories and confirm facts, in which sources and their motives are routinely questioned … this was the ultimate supporting proof.”

Pierre-Paul derides this logic in his initial filing, and his opposition to ESPN’s motion to dismiss includes 13 pages of negative tweets in response to Schefter’s tweet containing the photos. As someone who follows the news and as a citizen, though, you should want Schefter to have published those photos, and you should support laws that allow him to do so.

For far too long, journalism was in practice less the art of informing the public than of keeping information from it; a published story was a limited sample of the material reporters actually knew, filtered through invented codes of ethics and propriety. Sportswriters in particular were incredibly friendly with their subjects, routinely burying negative stories about them in exchange for access.

This is why disreputable gossip reporting and muckraking have always existed, and why the public benefits from them. Real events in the real world tend not to be pleasant and tasteful, and the work of documenting and explaining those events sometimes has to be unpleasant and distasteful in turn.

So against the various theories of restraint and suppression stands the principle that journalists should, in practice, share as much information as possible: Give readers the context they need to draw their own conclusions, instead of telling them what the conclusions should be. Publish documents in full, rather than merely quoting or paraphrasing a few lines. Let readers see photographs and videos, rather than simply describing them. Describe the sourcing and mechanics behind the reporting.

Even if Schefter somehow overstepped some line of “ordinary sensibilities” in publishing the photographs, his instinct to do so was the same instinct all journalists ought to have—and one that a substantial body of case law encourages American journalists in particular to cultivate.

On a more practical level, Schefter is also correct when he says that “sources and their motives are routinely questioned.” A factual assertion, no matter how thoroughly reported, will reach more people if it is accompanied by direct corroborating evidence.

“The idea at the time is that we would be the place that posted paper to the internet,” Bill Bastone, editor of The Smoking Gun, which specializes in obtaining and publishing source documents, told me about its founding in 1997. “We learned quickly, much to our dismay, there were a lot of people out there who would say, ‘I am so happy to see the underlying documents because I don’t believe what I read in the newspapers, and I want to see the primary source documents.’”

The public’s trust in the media is at an all-time low, with only six percent of Americans saying they have “a great deal of confidence” in the press and 41 percent saying they have “hardly any confidence at all.” Whether or not Americans should have more faith in the press—and for reasons that would take a book to begin to describe fully, the press bears heavy responsibility for the predicament it finds itself in—the fact is that they don’t.

“Nobody thinks anyone is straight anymore, in terms of the account that you provide someone,” said Bastone. “I always think, when some public figure dies, no one can ever believe that someone just died. There are already conspiracy theories about it and false flags and ridiculous shit that gets churned up, so why would anyone believe any thing else?”

This distrust has very real and negative consequences. Donald Trump lies daily, and these lies are dutifully debunked by certain sectors of the media. But in part because Roger Ailes, Matt Drudge, Andrew Breitbart, and their cronies spent the last two decades successfully indoctrinating a generation of conservatives in the belief that the mainstream media was liberal and therefore not to be trusted, half of the country doesn’t believe the debunkings. When Trump hijacked Fox News, Breitbart News, and other merchants of right-wing outrage to win the Republican primaries, establishment Republicans who for years had benefitted from and cynically fanned the flames Ailes had stoked were unable to stop him. Why? Because they’d taught voters not to listen to the press.

The public reaction to Schefter’s publication of Pierre-Paul’s hospital records reflects social changes more profound than those surrounding just the press. There has been a dramatic shift in the past few years in how the public feels about privacy.

In the early 2000s, when the share of Americans using the internet at home had just passed 50 percent, being online still felt anonymous. Siloed portals like AOL and Yahoo dominated access, and the average user had a sense that the barriers being broken down were principally the ones that had separated ordinary people from powerful ones: celebrities, government officials, the media.

As the internet became more central in daily life, and as users began building public identities across Gmail, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other services, people began to feel more personally exposed. They became aware that their internet behavior was being endlessly mined to offer up disturbingly precise advertising; their naked pictures were shared with strangers for pornographic purposes; widespread breaches of financial information became commonplace; and Edward Snowden and other whistleblowers revealed just how indiscriminately our own government vacuums up our metadata.

This sense of vulnerability, and an accompanying desire for privacy protection, has come on rapidly. One surreal aspect of the Hogan trial and its coverage was how disconnected the discussion of Gawker’s Hulk Hogan post in 2016 was from what the discussion had been when it was published in 2012. The fact that Hogan’s sex video had been widely covered four years earlier—and that two different courts had deemed the publication of illustrative video clips from it newsworthy—seemed to have become retroactively unthinkable.

And in the journalistic death-struggle for a share of declining ad revenue, denouncing a competitor for supposed privacy violations is a handy cudgel. The New York Post gleefully covered and cheered Hogan’s victory in the civil trial against Gawker Media. Three months later, the Post was publishing the sexts and selfies of Anthony Weiner, acquired and reproduced without his consent, on its front page.

To a certain degree, privacy norms in journalism are self-regulating. Many journalists would be uncomfortable working at gossip rags; many Americans think these publications are trash and don’t support them; and many advertisers are uncomfortable associating their brands with them. When publications overstep boundaries and are sued—every publication, no matter how upstanding, eventually gets sued—they settle cases or have to waste time and money on lawyers getting frivolous suits dismissed. The structure of the system has several strong, built-in mechanisms to limit invasions of privacy.

What a lawsuit like Pierre-Paul’s is positing, though, is something more structured and severe: a new formal principle, defining a medical record as inalienably private and unpublishable. But you don’t have to stretch very far to see a scenario where much more than the Giants pass rush would depend on private medical records. For months now, conservative internet sites have asserted that Hillary Clinton is unhealthy and unfit to be president, a conspiracy theory Donald Trump has promoted that recently crossed over into the mainstream. Trump’s own mental health has been the subject of speculation. If either presidential candidate had a possibly debilitating condition, and a journalist had the medical records to prove it, publication would undeniably be to the public’s benefit.

Given this, the specific premise of Pierre-Paul’s suit—that there’s no need for the public to see images of actual records when words will do—is insidious. The more indirect the evidence in a story is, the easier it is to deny or downplay. This isn’t a hypothetical, and NFL fans know it better than almost anyone.

In July 2014, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell suspended then-Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice for two games after he was arrested and charged with assault for striking his then-fiancée Janay Palmer in a casino elevator. (Rice entered and completed a pretrial intervention, leading to the charges being dismissed last year.) When Goodell made his decision to suspend Rice, he had access to footage of him dragging a limp Palmer out of an elevator, the police report, and a personal interview with Rice.

After TMZ published a second video, showing Rice striking Palmer in the elevator, the Ravens released him, the NFL suspended him indefinitely, and Goodell admitted that the NFL’s domestic violence policy was inadequate.

What had really changed? Not much. Goodell knew, or should have known, both that Rice had struck Palmer unconscious in the elevator and what that looked like. The material facts of the case didn’t change between Rice being on the Ravens and ultimately never playing in the NFL again; what changed was that visual evidence forced Goodell, the Ravens, the press, and millions of NFL fans to squarely reckon with what Rice had actually done.

But Jason Pierre-Paul is just an NFL player and his ability to play football doesn’t matter, you say. It’s not like he knocked his fiancée out in an elevator. True! But the First Amendment doesn’t only protect coverage of elected officials or of public figures accused of serious wrongdoing. Sports, entertainment, business, culture, technology, and a myriad of other subjects are of interest to millions of people, and worthy of critical coverage.

Some people are unquestionably private individuals; everyone would agree that publishing the medical records of a random toddler from Des Moines would have no public benefit. Between the poles of certainty represented by Clinton or Trump and our imaginary toddler, though, lies Pierre-Paul’s case. Given his public profile, the intense public interest in his health, his admission that Schefter was entitled to generally report on his health, and the very limited amount of information contained in the photos, it would seem Pierre-Paul’s case is much closer to the Clinton-Trump end of the scale.

If Pierre-Paul’s charts are off limits, or even conceivably off limits, where does the boundary fall now? The mere existence of the case puts journalists on notice that facts and documents, the basic materials of the job, might be unsafe to use. Forty years of what seemed to be established media law are suddenly being reopened.

U.S. District Court judge Marcia Cooke’s two-page order denying ESPN’s motion to dismiss Pierre-Paul’s lawsuit refers to the Supreme Court cases Bartnicki v. Vopper and New York Times Co. v. United States. The latter is the famous 1971 Pentagon Papers case, which held that the press can publish information of the public concern stolen by a third party, while Bartnicki held that the press cannot be held liable for third party violations of the law.

The importance of these cases should be self-evident. Together, they broadly establish that the press is allowed to possess, publish, and report on information of public concern as long as they did nothing illegal to obtain it. These rulings are what give the press confidence that reporting on newsworthy revelations from Edward Snowden’s NSA files, the Sony hack, or Wikileaks’s database of Democratic National Committee emails, won’t put them out of business or in jail.

But Cooke’s order goes beyond radically rethinking what types of corroborating evidence constitute an invasion of privacy when she gives credence to one of the main arguments Pierre-Paul advanced in his opposition to ESPN’s motion to dismiss: “Where, as here, a defendant accepts information from a source with knowledge of the illegality of the source’s disclosure, the defendant has unlawfully obtained the information and is not shielded against liability for subsequent disclosure.” In other words, if Schefter knew that his source’s disclosure of photographs of Pierre-Paul’s charts was illegal, the First Amendment, Cooke says, may not protect him.

Under current practical understanding of the relevant law, this argument holds no water. Pierre-Paul cites Boehner v. McDermott, a case in which John Boehner successfully sued Jim McDermott for disseminating a recording illegally taped by somebody else. The judgement against McDermott was eventually upheld after a 10-year-long legal odyssey, but that was only because one judge didn’t believe Bartnicki even applied to the case, and four judges believed McDermott had a “special duty of nondisclosure” due to swearing an oath to comply with House of Representatives ethics rules. Schefter, obviously, did no such thing, and thus could not have similarly forfeited his protections under Bartnicki.

It is important to note that Judge Cooke’s ruling was just an initial order, and that she was required to assume everything Pierre-Paul argued was true. But in her reasoning, Cooke signaled an openness to Pierre-Paul’s desire to extend illegality one step further down the food chain to Schefter, and all journalists, a result that has enormous implications.

“From a First Amendment perspective, it simply cannot be said that the simple acquisition by a journalist from someone who had no authorization to provide the information can make the journalist fairly characterized as having acquired it unlawfully,” Floyd Abrams, the lawyer and First Amendment expert who won the Pentagon Papers case and a slew of others, told me. “That sort of ruling would imperil a good deal of information.

“Someone has access to information, which is by its nature private, the person is not allowed to reveal it, a revelation is made to a journalist, and the journalist publishes it. If that makes the journalist on the same level with the hospital person who provided the information, that would be a real gash into First Amendment protection.”

As Abrams tells it, most notable First Amendment and privacy cases have dealt with the written word, simply because photographs and video are relatively recent inventions, and until recently it wasn’t easy to publish them. But with everybody now owning a smartphone and barriers to publication effectively gone, that has changed. The courts are grappling with these changes, and early indications are that they’re inclined to reverse, rather than promote, the longstanding trend of supporting the right of the press to publish accurate information. If a federal district court judge is going to seriously entertain the notion that Schefter isn’t protected by the First Amendment if he knew the actions of his hospital source were illegal, we’re through the looking glass.

Apart even from the question of whether Schefter may be tainted by someone else’s lawbreaking, the judge also wrote that “federal and state medical privacy laws, though not directly applicable to Defendants, signal that an individual’s medical records are generally considered private.” This would imply legal rules specifically written to govern professional obligations in the medical field are now a standard for judging journalistic decisions.

There are indeed laws which heavily protect medical records, but they only apply to a certain subset of the population; I am allowed to tell my friend that you have a flu, even though your doctor cannot. In contrast, the conduct at hand in the Bartnicki and Boehner cases—wiretapping, essentially—is illegal if anybody does it. If anything, Abrams argued, that means that the information disclosed in the Pierre-Paul cases should be considered less worthy of protection than the information in the Bartnicki and Boehner cases.

Even if Pierre-Paul’s suit isn’t ultimately successful, its even being allowed to continue in court is a weakening of law that has protected journalists for decades, that has emboldened them to pursue stories of incalculable benefit to the public.

This lawsuit is, among other things, a sign of how powerful the forces pushing journalism towards public relations have become. There is a reason why many of the most successful digital media operations are essentially branded-content studios masquerading as journalism shops—it’s because journalists and media organizations are afraid, and they should be. They’re afraid to publish information as the laws surrounding it are rewritten right under them, afraid of angering the wrong thin-skinned billionaire, and afraid of a public that not only doesn’t seem to mind, but if anything, is actively cheering these developments on.

There’s an irony here: Adam Schefter is a scoop trader, trading tidbits of information that lead to him breaking news that will just be announced by teams in a half-hour anyway. Among sports fans—or at least fantasy football players—there is an insatiable appetite for this type of news. But judged by the quote of unknown provenance that journalists love to cite—“Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed: everything else is public relations”—Schefter is a flack. There is something darkly comic about the fact that a crucial First Amendment case rests on him, of all people, having published something somebody else didn’t want published. But as we learned a long time ago with Larry Flynt, it’s usually the unlikeliest of characters whose actions define First Amendment law.

Even moreso, though, law is ultimately defined by the public whose democracy the First Amendment expresses and in theory protects. Despite what judges might have you think, their opinions are not necessarily based in scrupulous neutrality, but tend to reflect the prevailing moods and sensibilities of the public. A public that wants to be less-informed will find a way to be so; like their governments, the press the people get is in the end the one they want and deserve.