Major League Baseball saw attendance decline for the fifth straight year, falling to a mere 28,198 fans per game, the lowest mark since 2003. It’s a trend that has already prompted much public hand-wringing from baseball barons and the sportswriters who care about them: MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has said the sport needs to work harder to appeal to fickle millennials, though far more likely theories are that too many teams are setting ticket prices too high (as I theorized here a few weeks back) or giving up on competing before the season even starts (which Rob Arthur calculated is responsible for about one-third of the attendance drop at Baseball Prospectus about a week later).

The latest pontificating came from The New York Times, which ran a long article on Sunday about baseball’s attendance decline (“Baseball Saw a Million More Empty Seats. Does It Matter?”). Because it’s the Times, the article, which took four people to report, tried to cover too many things at once and also included lots of confusing charts—excuse me, data visualizations. (Why does “Average Yearly Ticket Sales” show per-game averages, exactly?) But its upshot mostly came down to two points:

- It doesn’t really matter to teams how many fans show up to games, not when they’re making record revenues (up 70 percent in the last 10 years) thanks to charging fans more in media rights fees to watch at home.

- More MLB teams (18 out out 30) are experimenting with subscription-based models where fans pay a monthly fee to go to an unlimited number of games.

These are sort of unrelated, if not downright contradictory, arguments: If teams don’t much care how many people are showing up to the ballpark, why are they offering new lower-priced ticket options to get more of them to show up? The article hints at a generational explanation (“baseball executives believe it is attractive to younger fans, who are used to paying for subscription services like Netflix and Spotify”) without any evidence at all, suggests that watching baseball on TV doesn’t create real fans (“nearly everyone in baseball agrees that the surest way to create lifelong fans is to have people play the sport and attend games”)—and then points to a reason why teams wouldn’t want to do this in the first place:

“If teams lower ticket prices too much, they could devalue their product and drive away those customers who still pay hundreds or thousands of dollars each season for a premium experience.”

That is not quite right: Rich fans aren’t going to stop going to baseball games just because they have to rub elbows with young cheapo subscribers. (At least, most aren’t. And you can placate the exceptions by offering them special entrances and special clubs and the like.) What is true is that customers may be driven away from spending big money when they realize that they can have a very similar experience by spending a whole lot less.

(Let us pause here to note that spending “hundreds or thousands of dollars each season” isn’t actually a lot. Those discount subscriptions to Oakland A’s games, for example, run $33 to $75 a month, which comes to $198 to $450 a year, which is “hundreds” right there.)

This is something I noted briefly in my “What’s the Matter With Baseball?” Deadspin piece, though I ended up trimming some of the discussion for length. Here’s the bit that ended up on the cutting room floor:

In fact, there’s a fair bit of evidence that pricing some fans out of going to games is intentional on the part of team owners. In his subscribers-only newsletter, former SBNation baseball editor (and sometime Deadspin contributor) Marc Normandin notes that remarks by team execs about keeping prices high to “protect the investment” of season-ticket holders have an obvious subtext: “The investment the teams want to protect is the chance that those season ticket holders will once again pay an absurd amount of money to guarantee the same seat for 81 home games in the following season, even though there are empty seats all over the park they could choose to pay for when they feel like a game. If season ticket holders take too much notice of the fact that they don’t need season tickets in order to attend MLB games on the regular, then teams won’t sell as many season tickets.”

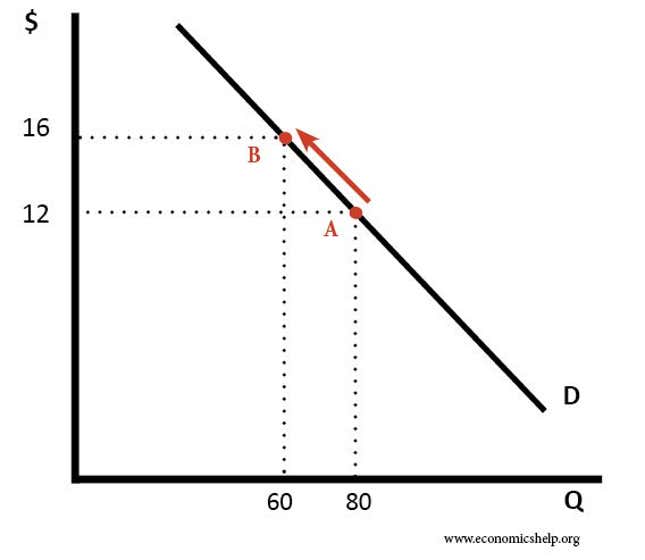

What’s going on here is an attempt by team owners to navigate a longstanding microeconomics problem: How to capture all of the value under a demand curve. Allow me to illustrate using one of many basic demand curve illustrations all over the internet:

When you raise prices (in this case from $12 to $16), fewer people buy your product (in this case 60 people instead of 80). Since your revenue depends on the number of items you sell times the price—we’ll ignore the cost of producing more items for the moment here—you want to set prices at a place that maximizes the area of the rectangle under the curve. (In this case, both prices earn you the same amount, $960.)

Ah, but what if you could capture revenue representing all the area below the diagonal line? That would mean selling your product for more money to people who are willing to spend more, while simultaneously selling it for less to lure in people who will only buy at a low price. Which is exactly what teams try to do by selling “premium” seats vs. cheap ones.

It’s precisely that dynamic that airlines try to exploit in selling business class seats vs. economy, or that streaming video services do by offering HD vs. SD movie rentals, or really that any industry does that offers separate premium and discount options, at wildly disparate price points—sometimes, with absolutely no relation to the actual cost to the company. What from the consumer’s point of view may look like an attempt to cater to every specific need is also a profit-maximizing strategy: The more you can slice up the market into ever-smaller gradations of demand, the better you can squeeze the most cash out of customers who are willing to part with it, without driving away those who are less eager or able to spend big bucks.

The trick, then, is not to let the premium payers get tempted into buying the cheaper alternatives. So there need to be hard lines of distinction: members-only clubs for those who pay more, in-seat wait service, strict rules about who can and can’t use which bathrooms.

Getting back to the Times article, we now have the missing link between team owners not caring too much about attendance and simultaneously caring so much that they’re offering all kinds of new ticket deals: It’s not a contradiction at all. Of course teams want to sell as many tickets as possible, but only if it doesn’t cut into their existing high-priced sales. Things like membership cards for standing-room only admission, then, are their way to try to have the best of both worlds: Keep on gouging rich fans, while getting less well-heeled or more casual fans to pay whatever they’re willing for a lesser version of the same product.

In other words, though the Times article hedges on answering the question posed in its headline, Betteridge was right in this case: Baseball’s attendance problem isn’t so much a problem as the logical outcome of a marketing strategy. If MLB teams wanted to sell more tickets, they wouldn’t need to suss out the particular desires of phone-happy younguns or the exact calibration of how many home runs is too many; they could simply lower prices, and maybe start spending enough money on players to give fans some reason to come out and watch, and the seats would fill with fannies. Which means the logical corollary is: If stadiums are empty, it’s because team owners would rather have it that way—at least until they can figure a way to have their cake and eat it too.

Neil deMause has covered sports economics for more publications than even he can shake a stick at. He’s co-author of the book Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money Into Private Profit, and runs the website of the same name.