Ron Fellows played cornerback for the Dallas Cowboys and Los Angeles Raiders from 1981–1988. He intercepted 19 passes and scored three touchdowns, including two on interception returns. Now 61 years old and living in Sacramento, Calif., Fellows suffers from Alzheimer’s, and his cognition is gradually declining. What follows is a description of life from the perspective of Debra Fellows, Ron’s wife since 2002, as told to Dom Cosentino.

Just recently, Ron’s best friend, who played for the Raiders, called me and said, “He’s getting worse isn’t he, Deb?” And I said, “Yeah.” And he hasn’t seen him in person for a couple of months. He said, “I can hear it on the phone ... He’s angry all of the time.” And I said, “Exactly.”

The one thing he does that has always cleared his head is golf. And I had another guy call who he golfs with, and he said, “Did I do something to offend him?” And so I had to explain—and I had explained it to him before, but he still wasn’t getting it. He has two grown sons that are twins and they’re 21 and they have autism. And so after I pointed out some of the similarities, suddenly it all dawned on him that that’s what was happening. All of us are withdrawing from people on the outside.

Other people don’t see that. Ron was diagnosed about four and a half years ago with Alzheimer’s. One of the biggest frustrations of all of the wives or kids or whoever is the caretaker of the person with something like this, is that nobody gets it. You try to explain it to the family, the extended family who isn’t around the person all the time—my husband’s family, most of them live in Kansas, and back in that area—and I get comments like, “Oh, he just had his mind on something else.” It’s always an excuse, and whether it’s denial, or just not understanding, I don’t have a clue anymore, and it’s extremely frustrating. Countless wives are going through the same thing. How do we get the general public to get it?

I talk with people who are living the same nightmare, because you don’t have to explain yourself, and it gets exhausting to explain yourself. I mean, how do you describe it? And that’s what’s so frustrating to me, because it sounds so benign when you talk about individual little things, but collectively they’re huge.

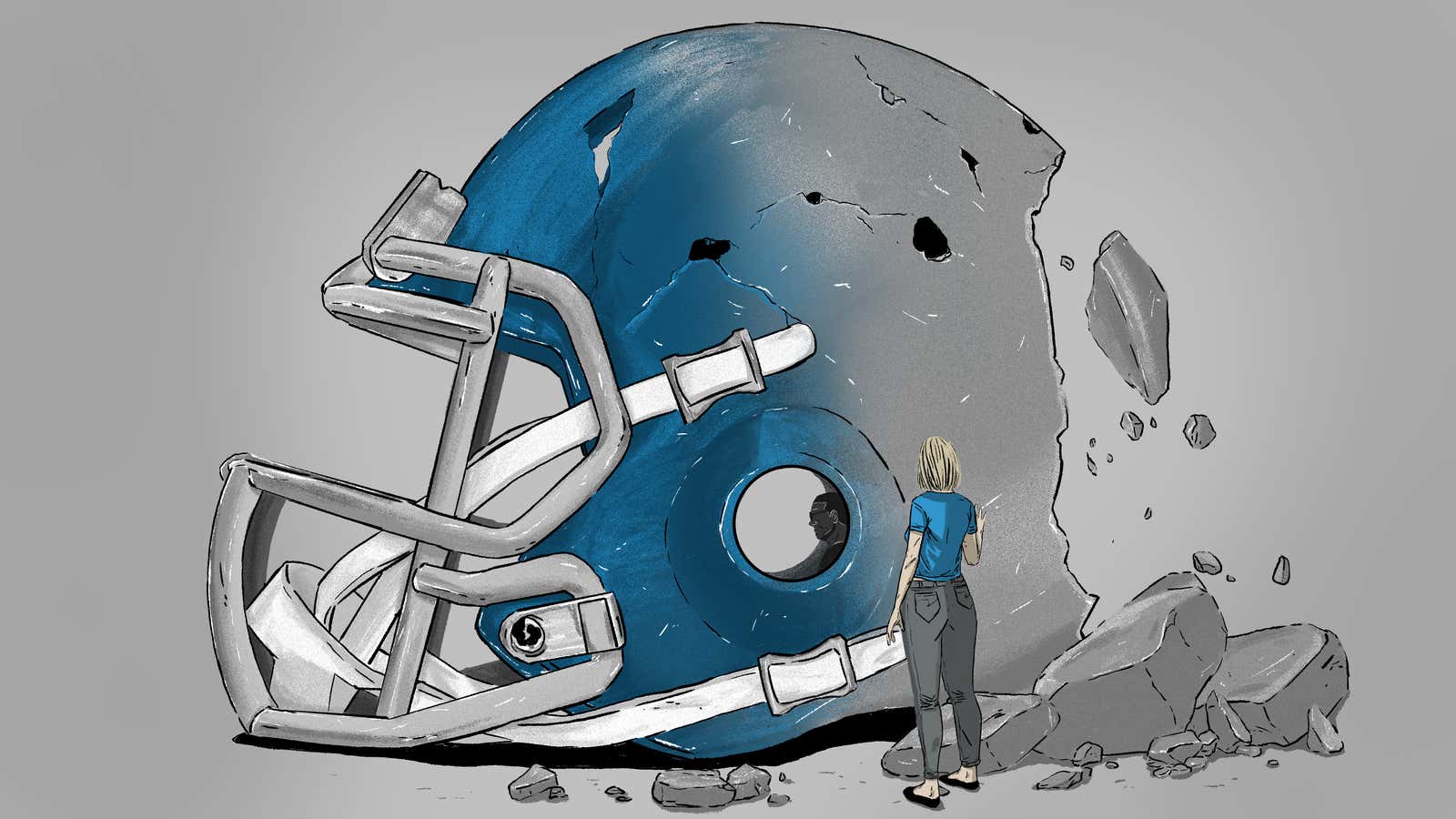

When you tell somebody he has Alzheimer’s, they immediately—and I have medical training—they equate it to their grandmother’s Alzheimer’s. Oh, they just sit and stare into space. And so now I don’t even use the word any longer. I say my husband has brain damage because I’m thinking, well, maybe they’ll understand it then.

How can I get people to understand? I have literally ended friendships because people didn’t get how my life adjusts daily according to what’s happening at home. There’s somebody that I’ve been friends with since we were in first grade. She and her husband and Ron and I had dinner together, and I talked to her, and I told her that Ron had Alzheimer’s from football, and explained some of the things that were going on. I had re-posted something having to do with Alzheimer’s on my Facebook page, and she proceeds to send me a text that said, “I just read your Facebook page. What’s going on?” I wanted to beat my head against the wall. I said, “I told you over a year ago that Ron has Alzheimer’s. That is not me describing Ron. I was re-posting an article that was an informational article, and I’ve been going through a lot.” And then I didn’t hear from her for another four months. Because they just don’t understand.

My husband is probably one of the most meek and mild-mannered guys you’d ever want to meet. And he has never had a sip of alcohol in his entire life, just because his dad was a mean alcoholic and he never wanted to be like that. But for about two months he was angry and biting my head off and hanging up on his best friend—zero tolerance for anything. They had just increased one of his meds, and so I thought, Maybe I’ll give him another week or so. Finally, nothing had changed, so I message the doctor and he put him on another medication, which now seems to be helping a little bit. You’re in that position where you don’t want to overmedicate them, but you also don’t want to live with that every day.

And then when I say he has anger outbursts, people just sort of brush it aside, like, No big deal, everybody gets mad once in a while. They don’t understand the intensity of it, and how out of character it is, especially for my husband.

Several weeks ago, I was getting ready to walk up the stairs, and I had just been really quiet because I didn’t want to engage; I didn’t want to get in an argument. This is when he was going through his really angry period. And so it was just better not to talk because everything turned into an argument of some kind, even asking him what he wanted for dinner. So I was getting ready to walk up the stairs and he said, “What’s wrong?” And I said, “I don’t know, I’m just feeling a little down today.” And he jumped up off the sofa—he was watching a Western—he jumped up off the sofa and said, “I can’t even watch a goddamn Western!” And so I had to put the emotion aside, and say, “Okay, it’s the disease.” There was nothing in that exchange that had anything to do with him not watching his Westerns. He asked me the question. And in retrospect, I probably shouldn’t have even bothered answering and just said, “I’m fine.”

During that two months when he was angry I had to move on and pretend it didn’t happen. About two weeks after he changed medications I talked to him about it, and I said, “We need to talk because this is really hard for me.” I said, “I need you to know that when the doctor changes the medication, it’s so that you are happier and you are able to function better because your brain is not producing whatever it is that is taking place at the moment. We’re not doing this because we want you to take so many pills.” I have to be very careful how I explain it to him. And he said, “No, I know.” He said, “I’m sorry for the way I’ve been. I can’t help it.” And I know he can’t. And that’s what’s so hard, and that’s what people need to understand. It’s impulsive, it’s quick, and it happens, and they may not realize it at that very moment, but they realize it. And then it creates more anxiety and heartache for them because they don’t want to treat people they love that way. And that’s the hard part. Because he doesn’t like it any more than I do. But I at least have the ability to realize it’s the disease.

He’ll have a decline, and then it evens out for a little while, and then—boom!—there’s another one. But every day, because you never know what to expect, is like walking on eggshells. He had a black-out rage a while back where he walked into the room and he was staring straight ahead, and he was ranting and raving about something—still, to this day, I have no idea what. And, usually, when I say, “Ron, calm down,” he will snap out of it and calm down. He then raised his fist—but he was still staring straight ahead with this blank look. It wasn’t directed at me, but still, you have that little question mark, like, Well, maybe? I know enough medically not to engage. And so he said, “Shut the fuck up before I bust your lip!” So I walked out of the room, and I just waited for it to pass, and a few days later I asked him, to see if he remembered. “Who were you so angry at?” He goes, “I never said any of that. I would never talk to you like that.” So he was completely unaware.

He’s black. My other fear is that he’s somewhere and he snaps because of his brain, and God knows how it would be handled.

The general public thinks, Oh, it’s just a handful of guys, because of the NFL PR machine. They’d rather spend their money talking about how we’re all family, and they take care of their family. The Raiders had their alumni weekend a few weeks ago. You know what they had at the alumni weekend? An NFL town hall meeting. And if you had any questions you had to submit them 10 days in advance. [They do that] because last year the Legends Community was doing their little thing and I asked—I knew the answers—but I asked about 10 questions so other people would have real information. And so they probably thought, Oh, if she’s coming again we better screen the questions ahead of time.

It’s a horrible hell to live through. These last couple months have just about done me in. You want them to have the best quality life that they can, but I don’t want him going around drugged all day long. So you have to reach a happy medium, and thank God I have great communication with both our family practice doctor and Ron’s neurologist. They responded immediately, but it’s hard, and not everybody has the luxury of that, either. Especially the ones that have to get these MAF doctors [mandated by the concussion settlement].

Ron was diagnosed in 2015. At that point in time he was symptomatic in many ways. At times I questioned whether it was blood sugar fluctuations because he was moody—I used to refer to him as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—and impulsive. It has been extremely noticeable in the last year, which is a frustration for me to see what is going on now, with what the NFL is trying to do with these men because they expect them to be sitting and drooling to acknowledge the fact that they have any neuro-cognitive issues.

Ron did collect a settlement payment, but the delays were ridiculous. The questions, the things that they would come back with, and seeing what they were asking when it was right there in front of their face, was the most maddening of it all. And I thought, if they’re doing that to us, when we know exactly what they’re doing because the information is there, what are they doing to everybody else? Dr. Shawn Kile, who is Ron’s doctor—he does research with Dr. [Bennet] Omalu at UC Davis MIND Institute—he wrote this scathing letter, basically saying, How dare you question my diagnosis? Because Ron had had a PET scan, he had had everything done, and they asked, Well, why didn’t you do a spinal tap? And Dr. Kile just lost it. He said a spinal tap is an invasive procedure, there’s a high risk of infection, it doesn’t need to be done if you have a positive amyloid scan. It’s, like, Who do you people think you are? So anyway, two days later Dr. Kile wrote the letter, and they approved Ron’s claim.

And that’s why I keep telling people to stop being silent. Because the silence enables them to continue the delays. I keep telling them you need to stop being afraid of the NFL. What are they going to do? You have all your proof right there. Stop fearing them. But it’s been that way for so many years. The guys used to never say anything because the NFL would get them. Now the whole dynamic for that is changing. They’re all angry. They’re fed up. These guys are treated like yesterday’s trash. And it’s not about the money. It’s about the dignity and the respect. Listen, Ken Stabler—when I saw that his claim was denied, I’m sitting there thinking, okay, he had late-stage colon cancer. Now, you know what would have happened if he had gone in [to visit with a BAP or MAF doctor] the last three months of his life, even he was even physically able to go in and get tested? Do you know what they would have done? They would have blamed his brain fog on the chemo. It was a bunch of nonsense.

You know, my husband caught Kenny Stabler’s last pass that he ever threw. He intercepted it—and he still has the ball. It’s kind of cool, but it’s just sad, too. It’s really sad. And on top of that, to deny Stabler’s family the Hall of Fame ring and the jacket? I mean that’s part of his legacy. He’s not alive to wear it, but the family remains.

What they need to do is just shut the hell up and just pay the family, along with Pam Webster, and all of the other ones, and have a little respect for the people that built the league.

The Raiders recently had their alumni weekend. And even though Ron only played for them for two years, he has formed lifelong friendships with those guys. He has a lot of lifelong Cowboys friends, too. But there’s a different type of camaraderie with the Raiders alumni. The Raiders organization has actually made the effort to make them feel like family. And so I had declined the invitation because Ron had had a bad couple of months. The doctor changed his medication about eight weeks ago, and he’s starting to see a little bit better right now. So [former Raiders wide receiver] Mervyn Fernandez and [his wife] Brenda had talked Ron into just coming over for a couple of hours. But what was so heart-wrenching about it all was that as much as Ron had the desire to see his friends, he got over there and he talked to them for 15, 20 minutes, and then I was sitting there with Brenda and a few other people, and they turned around, and he was standing by the wall, by himself, just gazing around. And that is so not like the normal Ron; he’s usually very engaging and likes to trash talk with all of them. It broke my heart.

He’s just withdrawing. He’s not engaging with people because, first of all, his brain at times doesn’t allow him to, and secondly, as the disease is progressing he is uncomfortable because he loses words, so he feels as if he can’t have a conversation. And so when he only is on the telephone for 30 seconds or something and hangs up, people get offended, because they’re saying, Well, what’s wrong with him? And his family. They don’t understand. They all live in Kansas or Chicago, and they don’t understand that for a brief moment or two, he sounds like himself, but he’s not.

He will share with me, “I feel uncomfortable when I go to play golf because I start to have a conversation with somebody and I stop because I can’t think of what it was I wanted to say, and I’m afraid that if I started talking I won’t be able to say what I have intended to say.” And so there is this silence. That’s what was so striking about the alumni event. He has retreated to a quieter place or become very quiet in groups of people, or if it’s really noisy. But this was the first time so quickly into being someplace that he just was standing there looking around. And then all of a sudden I get this text message that says, “I’m in the car.” So it was time to go.

If you looked at Ron, you’d think, Gosh, he could probably still play football. He physically looks like the picture of health ... I don’t want him to be treated like an invalid. But I want people to just manage their expectations of him. I want them to not put more stress on him than what he’s dealing with. And I think that’s pretty much what all of the caretakers and wives and kids are feeling. They’re not okay. Don’t tell me they’re okay, or that they look fine. Nothing makes us more frustrated, because then you start doubting yourself after a while. And the last thing—the last thing—that I want to do is to embellish what is going on with him. I am trying to keep him as healthy and active and have as much quality time as I possibly can.

I tried to tell one of his sisters I am in a constant state of grieving. Every day, I lose a piece of my husband. Every day, I lose a piece of the man I fell in love with. And it’s heartbreaking to me because Ron and I have always had this really wonderful, happy, bantering relationship. He’s my best friend.

With our foundation, I have been working with one of the neuropsychologists here in town, and we’re going to start a support group for wives, and one for the men, that are separate, so that they can start talking with one another about it. And it’s great to have a support system online with other wives and all of that, but the physical interaction of being present and having somebody be a facilitator that is knowledgeable about the disease is also important. People don’t understand that they have brain damage. Ron has frontal lobe [damage], temporal lobe [damage], he has amyloid throughout his entire brain. He has 76 percent blood flow to his brain, and different parts of his brain fire at different times. So it’s not just one area that is going to present a certain group of symptoms. One day it might be personality, the next day it’s memory. But none of us know what we’re dealing with from one minute to the next. So you spend your life walking on eggshells.

It’s a full-time job. My life revolves around Ron. I may not be changing diapers or having to feed him or things like that at this point, but just managing everyday lives is a full-time job. I have to manage everything because I don’t want to destroy his self-esteem. Because he’s already struggling enough with feeling like he’s losing some of his manhood because he isn’t able to do the things that he’s always done ... Other people always want me to go here, there, and everywhere. I don’t leave him. I can’t leave him.

I think that what’s hard is that it’s not organic. It’s not just a genetic disease, it’s not something that just came along. First of all, he loved the game of football. But [his brain damage] was caused for people’s entertainment and for the owners’ pocketbooks. And that’s what’s hard for me. I can’t even stand to see a football game on because I know what’s happening to them. If he knew what he was doing, then there’d be a level of acceptance because he made an educated decision. But it wasn’t an educated decision because they hid the implications.

I want people to understand—not only for the well-being of the players, but for the caretakers. Ron gets really sad. He gets really, really sad. He said to me a few weeks ago, “I wish I would have met you sooner so I could love you longer.” And it broke my heart. We thought we had all this time to be able to enjoy one another.