Tom Scocca is leaving us, after a combined six and a half years at Deadspin, Gawker, and the Special Projects Desk. Here’s how we’ll remember him.

Sam Biddle

One time I had an anxiety nightmare that consisted entirely of Tom Scocca walking up to me in a dark room (I was seated) and saying, “You’re a bad writer.”

Anna Merlan

I could talk about all the times that Scocca has miraculously edited my stories, adding single words or minutely adjusting paragraphs to somehow make the whole shitty thing hang together in a coherent whole, but I think that would make him uncomfortable and unhappy. Instead:

When I first started working at Gawker Media, back when there was a Gawker Media, we all sat together at long tables in a big room, a room that was alternately deathly silent and filled with some troll garbage someone put on the Sonos. Hillary Crosley Croker and I sat next to each other, and one day she could not get her computer to work. We tried to turn it on. Nothing. We stared at it and debated whether to call the IT people. This went on for some time. People started to look annoyed. Scocca, who sat next to us, quietly asked if we’d checked to make sure it was plugged in. In unison, Hillary and I whirled around and glared at him, as if to say, Can you believe this fucking condescending male piece of shit right here?

Seeing whatever was going on with our faces, Scocca apologized. Approximately two minutes later, we determined the computer was not plugged in.

We’ll be a measurably worse place without Tom here, but I will always cherish the memory of hotly despising him for several minutes, followed by immediately having to say I was sorry.

Kelly Conaboy

One time at karaoke I put in “Hanging on the Telephone” and Tom sang it with me and then told me it was a good pick. Thanks, Tom!

Jason Gay

I sat next to Scocca twenty years ago at a newspaper in Boston. It was the same, just without the Internet, or at least the Internet as we know it. I feel like I’m saying I saw a band in a small club. He’s the smartest person I’ve ever met, and I’ve met at least five baseball managers. Scocca was mad at Nike a lot. He also had a jaunty pair of red pants.

Gabrielle Bluestone

Tom is one of the smartest, sharpest people I have ever met and I feel extremely lucky to have had the opportunity to work for him. Getting edited by Tom was the intellectual equivalent of going to the car wash—he takes your messy copy and half-baked ideas, hits them with those soapy rubber things, shoves them through the air thingy, and ultimately produces something you might actually be proud to be seen in.

This metaphor also makes sense because both car washes and Tom are completely inscrutable to me. It took me three years to work up the courage to talk to Tom in the Gawker kitchen, and it didn’t go very well (I may have gotten nervous and accidentally said the word “dildo,” it’s hard to say), but not long after, we discovered a wealth of common dislikes that yielded a delightful ongoing conversation that outlasted my GMG tenure. I like to think that no matter where we are, we’ll always be able to look up at the same bad tweets and smile.

Leah Finnegan

Tom ... what is there to say. My life goal is to get a compliment from Tom. In the editing process, his icy silence meant I’d done something very wrong. I live in fear of it to this day.

Veronica de Souza

Tom and I were desk buddies for a few months, but we will always be birthday twins. The people contributing to this post will no doubt link to some of Tom’s “best work” so I’ll do the same: This is the best thing he’s ever written.

Bye, Tom! I will miss our slacks.

Jack Dickey

Is there any topic on which you wouldn’t be thrilled to read Tom Scocca? An object lesson: He wrote maybe a dozen posts about baseball in his time at Deadspin. This one from 2012, on his Baltimore Orioles (“They are bad, and maybe they are hopeless, but they are not hopelessly bad”), consists of several thousand words spotlighting replacement-level shortstop Robert Andino. I can’t make it through even Andino’s Wikipedia page without falling asleep. But in Scocca’s hands his tale turned into nothing less than the best story the site has ever published about baseball or fandom. He’s just that good.

Jordan Sargent

I think I can speak for all but like three writers Tom ever edited when I say I have no idea if he likes or respects me even slightly.

Tim Marchman

It’s been years since I wrote anything that meant anything to me that Scocca didn’t edit, whether in the talking ideas out before writing sense or in the him writing the best lines (the ones I would have written if I could have) and providing all the connective tissue sense or in the him producing his own copy of my draft after I’d deleted it in a fit of anxiety and then patiently constructing the piece for me while I fulsomely apologized sense. I can’t really turn to him to edit this, so I’ll leave it there.

Max Read

A lot of people—I am one of them—will tell you that Tom Scocca made them a better writer when they really just mean that he wholesale rewrote the bad copy they’d filed into something good. But I also mean that he made me a better writer because I no longer use the lazy descriptor “massive” except when referring to things with actual mass. In 2014, Scocca sent this short memo around to Gawker writers; it is surely not the first time the word massive has been forbidden to a newsroom, but as a lesson in the importance of words and the power of specificity it has stuck with me ever since:

What do Egyptian protests, a fatal wildfire, Jay-Z’s data-mining app, and the NSA’s spying operation have in common? Not much, really. So let’s strive to avoid calling them all ‘massive’ in headlines and leads. It’s a piece of newswriting jargon that essentially means ‘newsworthy,’ which is sort of implicit in the fact that we’re writing about them. Better to go ahead and use those eight characters saying what the news is. Or if the noun in question actually is something big or immense or sweeping, aim for the very best synonym from that family. Thank you very much.

Patrick George

I merely want to say that everyone who reads and enjoys our family of work owes Scocca a debt of gratitude. There were scores of stories that his deft editing hand made better, even on Jalopnik. “On Smarm” is required reading for all of my new hires and it always will be.

He also wrote a car review for us once, but people liked the one Hamilton Nolan wrote better. Sorry, Tom.

Alex Dickinson

Tom is a known genius but what no one ever talks about is how he has the best hair at GMG. He’s caught me staring at it. I will miss you, Tom.

Dave McKenna

I’ve known Tom Scocca since early in the century, when we worked together at the Washington City Paper. Back then he stored his guitar amp at my house, which is only worth mentioning because his amp had a volume knob that went up to 11—like the Spinal Tap gag, but for real. Even after he left City Paper, he still lived nearby and we stayed in touch. One day me and Tom and our mutual friend and D.C. typist Dan Steinberg met at a coffee shop. We were each fathers of one young child at the time, and I think we chose the place because it had a playroom. I was enjoying a rare conversation with grownups and totally ignoring the offspring until a ruckus broke out and I had to pay attention. I saw my four-year-old hurling chairs across the room at Dan’s three-year-old, who shrieked with glee at every tossed chair she dodged. But the most startling behavior in the coffeehouse that day came from Tom’s two-year-old, who was standing at a chalkboard in a corner of the coffeehouse while all the chair-throwing hell was breaking out around him and he was writing out ... math problems. I’d never seen anything like it. I mean, everybody knows Scocca’s a brainiac, but this was ridiculous. A two-year-old! I wanted to place a 911 call to MENSA. So while I haven’t heard what Tom’s gonna do next, I hope he’s giving up the blog life to manage the kid, since I’ve been sure since that day at the coffeehouse that we’d all eventually be working for him anyway. I’ve even got a chore for the father/son geniuses: I think the dynamic duo should go back to Scocca’s actual hometown, Aberdeen, Md., to solve the Ripken kidnapping case. Can’t wait for the movie! Good luck cracking that caper, and with all else, Tom.

Tom Ley

For most writers, particularly young ones, the internet is a minefield that is also patrolled by wasps. The dissolution of the old barriers to publishing has given a lot of people opportunities they would not have had in the pre-internet era, but it has also put every writer, at all times, every day, one false step away from self-destruction. All it takes is one ill-conceived Medium post, one self-absorbed personal essay, one poorly executed profile, and suddenly you’re a tragedy. A cautionary tale.

Worse things can happen. Some writers earn enough early success to land paying jobs at publications where nobody cares to edit them, and they go on to produce unremarkably bad bodies of work that never get them called out in public, only laughed at in secret.

Tom Scocca is the guy who stops people from doing that to themselves. Scocca was an editor at Deadspin when I started here, and I was intimidated by him. I’d never been in a newsroom before, but I knew that Scocca was precisely the kind of no-bullshit writer and editor that I didn’t want to embarrass myself in front of. That feeling of inferiority quickly gave way to the deepest feelings of appreciation.

Scocca had no idea who I was, or any reason to believe that I belonged here, and yet he treated me and my (mostly bad) writing with the utmost care. He took ill-conceived ideas and made them palatable, turned poorly written sentences into actual insights, and never made me feel stupid or inadequate while doing so, even though I mostly was. He made me less stupid. Eventually, all those edits imprinted some wisdom on me, and gave me the tools I needed to actually become a functional writer on the internet.

The internet is mostly bad, as is most of the professional writing being done on it, but people like Scocca stand against the tide of shit. He takes his job as seriously as anyone can, and he never shirks his responsibilities to the writers in his care. Every publication in the world would be greatly improved by the presence of Tom Scocca, and whoever gets him next should appreciate their good fortune.

Julianne Escobedo Shepherd

Tom Scocca once offered me one dollar to tweet something rude. I did it because it’s fun to be rude if you’re correct, but did not take the dollar because I would have tweeted it for free. More importantly, he walked all the way across the office to give me the dollar, because he is the kind of person who keeps his promises.

Lindsey Adler

Scocca once told me that I should “never trust an epiphanic writer,” and also asked me for advice on what type of skateboard to buy for his son. Proud to have had the pleasure.

Albert Burneko

In my professional capacity as, uh, a guy who has been writing stuff on the internet only for this one website and only for a few years, I have not worked with many editors, so saying any one of them is the most this or least that that I’ve ever worked with does not mean very much. Tom Scocca is the most meticulous and exacting and demanding editor of argument and argumentation that I’ve worked with, sure. But I have a lot more experience lowing takes at patient listeners than I do submitting my writing to editors, and Scocca is also, by quite some distance, the most meticulous and exacting and demanding audience for argument and argumentation that I’ve ever encountered.

Craggs would just cram his smarter, sharper, more succinct version of the argument into the blog wherever it fit best, in whole paragraph form, rendering the entire rest of the thing sadly redundant, and leave my byline at the top so that the praise that one paragraph and no other then received would hit my ears like a fart noise. Marchman would shave and sculpt in the best faith, honing the argument to the least bad version of itself but still at a fundamental level generously upholding the implicit arrangement that if I really wanted to publish a stupid-ass take on the internet for the whole world to see, his business was to facilitate my doing so. Scocca would not even open the editor. He would not displace a single mark of punctuation. He would just read the draft and then, in a series of Slack messages, tease it neatly apart into its basic components so that I could see how bad and stupid they were for myself, trusting that shame would move me to replace them with parts less bad and stupid, and then to assemble those parts less badly and stupidly. Then at some point I would go “Shit, man, I don’t think I’m smart enough to do what needs to be done here” and he would just write, for me, the couple of sentences that, when placed in the right spot, stitched things together just so.

What I would be left with, in the end, was this: I was (am, always am) tying language into stupid messy complex rhetorical knots just to bellow, bluntly, like an oaf, what pretty much always boils down to this is good or much more often this is bad, just these big boulderlike apocalyptic John the Baptist (or more probably Chicken Little) proclamations. This is what it means to be a big dumb idiot. Scocca, by almost total contrast, uses—discerns, first—the infinitely neater and more specific and more elegant arrangements of words and clauses and sentences that lead to observations so nuanced and sophisticated that I can’t even fucking understand them. That... well, maybe that’s not the only kind of smart, but it’s one kind, I think, and can’t really tell. I suspect it.

This made him a great resource. It also meant that in the pretty rare instance that a blog of mine warranted Scocca’s attention, it was always terrifying. I will have to rely on my Inner Scocca from now on, my integrated Scocca Voice, but frankly my Inner Scocca is a lot stupider than the real thing. This is bad, is mostly what he says, but he only says that. He does not dress it up with a lot of bullshit; he knows he doesn’t have to, and that’s something.

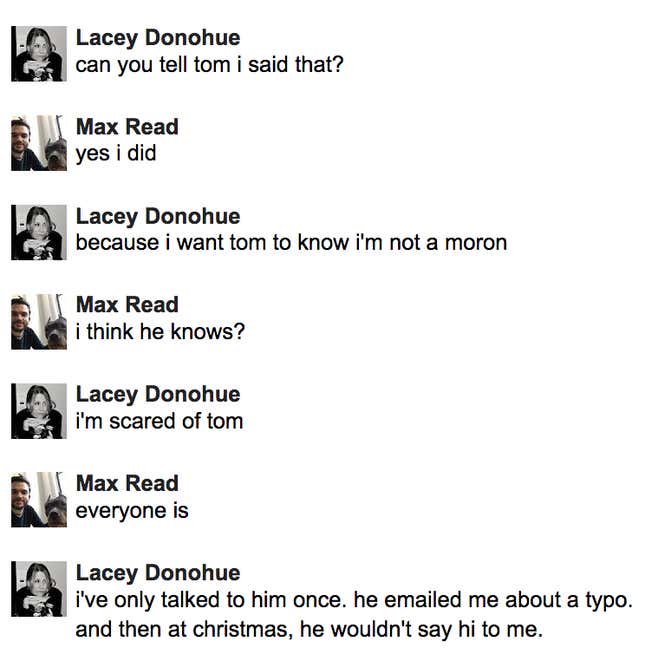

Lacey Donohue

Four years ago—a lifetime in Gawker years—I had the following chat with Max Read:

It’s a conversation that I think many of us in Tom’s world have had. These conversations always revolve around three basic feelings:

- Tom fucking hates my copy

- Tom fucking hates me

- Fuck, how can I impress Tom?

What people don’t realize in the moment, the moment where you’re trying to figure out how you’ll ever have a career because Tom Scocca hates your writing and simply hates you, is how lucky of a moment it is. Because sure, it’s embarrassing and awful and unsettling and you want to die, but at the end of the day, holy shit:

I get to live life knowing I’ve been edited by THE Tom Scocca. I get to live a life knowing Tom Scocca mostly doesn’t hate me. And I get to live life knowing that while I’ll never truly impress Tom Scocca (very few things impress Tom Scocca outside of a good seafood delivery from Fresh Direct), I got to work with Tom Scocca. I’d do anything for him because once I moved beyond his amazing hair and stern edits and forced my way into his life, I was lucky enough to befriend one of the greatest humans in this shitty world.

Fuck, I’ve written too many of these at this point to try and be funny.

I miss you, Tom. Thank you for agreeing with me that more than two drinks is always too many, but thank you for never judging me as I head for drink number five. Thank you for believing in me. Thank you for believing in Gawker. Thank you for always fighting and never ever giving up. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Congratulations on winning the suicide pact. Now all four of us can officially start living. No one deserves it more than you.

Dom Cosentino

When I began my first stint at Deadspin as an editorial assistant in July 2011, the site’s roster included Tommy Craggs, Barry Petchesky, Emma Carmichael, Luke O’Brien, Jack Dickey, Drew Magary, and another relatively new hire named Tom Scocca. The editor-in-chief? A.J. Daulerio. Scocca was supposed to replace Craggs, but Craggs’s departure hit a snag, a pink gorilla got involved, and somehow Daulerio got to keep both Craggs and Scocca. “Welcome to the A-Team,” Daulerio told me just before my first day at 210 Elizabeth Street. Christ, look at those names I just listed. That’s a Hall of Fame lineup, from top to bottom. I often felt like the bat boy or the popcorn vendor.

Understand: 210 Elizabeth had this dark, weird-ass newsroom that was church-mouse quiet; to communicate like fully evolved humans (i.e., by talking) was by no means prohibited, but it often felt that way. Anyway, Scocca sat next to me, where he would write posts stuffed with subtle and thunderous brilliance in between bouts of completely eviscerating my copy. We rarely spoke, in keeping with custom, and so I was terrified of him. That feeling of inadequacy, I now know, was entirely self-inflicted: There was a genuine esprit de corps that permeated that era of Deadspin. At the time, I was too dumb and insecure to realize how much I was learning from people like Scocca. I was a part of the A-Team, and I’m eternally grateful for that.

Also, I’ll never forget the look on Scocca’s face as we high-fived right after Notre Dame finally put out its statement confirming the Manti Te’o story, maybe an hour after Tim Burke’s and Dickey’s post was published. And ever since Scocca karaoked “Mele Kalikimaka” at the going-away drinks that concluded my first stint at Deadspin, I’ve been unable to hear that song without thinking of him. I hate that he’s leaving.

Conor Friedersdorf

Subject: Re: Tom Scocca roast

Thanks, Keenan, but I’ll pass; wish him my best as you send him off.

Cheers,

Conor

Sent from my iPhone

Jack Shafer

Tom always withheld his best work from Gawker and the Gizmodo organization in favor of Twitter.

Kavi Reddy

Tom gave me some of the baby advice: don’t buy too much crap, a bassinet is pointless because a baby can sleep in a box, etc. Also, Tom’s sweet account of cooking pasta with anchovies for his family in my all time favorite Gawker post, almost made even me (often accused of being cold and an unemotional robot) tear up.

Tim Burke

Tom Scocca is an alchemist, and in my seven years here he has transmuted my garbage sentences into golden paragraphs more times than I can count. Everyone should be so lucky as to have his influence making us look like such better, more clever, more insightful writers than we really are at least once in their life. That’s an incredibly awkward sentence, and I don’t even know if the point gets across, but I feel quite confident were he to edit it it would come out much more beautifully. And so we will all very much miss his brilliance, for as enriched we were by his presence we will be as diminished in his absence.

Mike Ballaban

I asked the rest of the Jalopnik staff if they had any Tom Scocca memories. “Remember to spend a week doing it and have no clear point,” Raphael Orlove said. “Just word salad for a while.”

Scocca wrote for Jalopnik once. Once. We had started a series where we would encourage non-car people to drive all sorts of fun cars, both because it provides a variety of viewpoints our readers might not normally get, and because it’s healthy. After getting Hamilton Nolan into an absurdly fast and expensive Lexus, we decided to put Scocca into a Camaro. He’s got that Camaro-driving look, of course.

He informed us that he had kids, and that a Camaro, with its tiny back seat, couldn’t possibly work. So instead we got him a different car, a Cadillac CTS V-Sport. Not quite a Camaro, but still, with Tom Scocca writing the review it was sure to be gold. He’d written for Slate a couple of times, after all.

We got back 3,240 words that barely made any sense, a large portion of which concerned the philosophy of proper seat adjustment. It sat for months, unedited, as we had no idea where to even start.

“What’s the main thing you want readers to understand about this car?” we asked.

“The identities we construct through and around our consumption of commercial products are tissue-thin and contingent,” he replied.

No, we don’t know that means, either.

But frankly, we didn’t care. Tom Scocca was, is, and always will be, one of the greats. So we made it the headline. And we didn’t change a single one of his 3,240 words. Even if they didn’t make any sense.

We’ll always be indebted to Tom for the immense support he’s given all of us at Jalopnik over the years. He’d poke and prod at a number of our larger features as a matter of course, always providing insightful comments that we’d never dream of ourselves. What mattered more, however, was “On Smarm.” No one could quite encapsulate the guiding ethos of everything this company did like Tom. No one could quite embody exactly what were we going for with every short dumb bloggy post we did without his ideas supporting it.

We still have no idea what his review was about.

Kashmir Hill

It was one of the great joys of my last year to have Tom read a draft of one of my stories and then to bombard me with Slacks expressing his outrage at the facts therein which would perfectly sum up all the big ideas the piece touched on. I would then steal that language and inject it into the story. “It’s not stealing!” he wrote back once. “This is what I type the words in the box for.”

Tom’s perception of what should outrage people is finely honed and eloquently expressed. I’ll miss it.

Andy Cush

My best Tom Scocca story involves the most ambitious piece of journalism I’ve ever attempted, which he edited. Putting the story together took many months, and frequently felt like a slog: Tom asked me to make more calls when I’d already made dozens, dramatically altered the piece’s structure a day or two before we were slated to publish, urged me to go to Nashville for a single day just after Christmas to conduct an interview that would last only slightly longer than the duration of the flight. All of this was frustrating on some level at the time; more importantly, all of it made the piece much better than it would have otherwise been.

But my most vivid memory of Tom’s work on that piece has more to do with his ferocious and terrifying attention to detail than it does with broader instincts about reporting and storytelling. 2,000 words into a 10,000-word story that also included citations from police reports and court documents, I’d written a scene around a conversation I’d had with a source in the front yard of his house in Missouri. “A litter of newborn kittens rolled around in the overgrown driveway,” my draft read, a sentence that Tom flagged almost immediately after I filed it. He pointed out that truly newborn kittens are helpless creatures, incapable of seeing their mother in front of them, much less rolling around in the driveway. I couldn’t believe he’d zeroed in on this one extremely minor error, but of course he was right, and the fact that he found it is a testament to the rigor of his editing. We changed the phrase to “tiny kittens” instead.

Melissa Kirsch

I will never forget when Tom told me he had completed what was to be his most incisive piece of cultural criticism yet and would I do him the honor of publishing it on Lifehacker? Yes, I told him, I would be a fool not to, and so

“On Smarm” was unseated in the popular imagination.

Puja Patel

Jia always said he was a great editor.

Jia Tolentino

The first time I DMed Tom Scocca over Slack to make him edit something I was writing, I was so stoned that I definitely shouldn’t have been at the office and in fact I thought I was DMing Tommy Craggs. Gradually, over the course of a half-hour conversation, I realized that the obscure koans and abstract portentous observations I was receiving as feedback were not actually issuing from Craggs at all. From that point on, however, I sent Scocca every single thing I needed help with, and when he would get back to me, two weeks to seven months later, the experience of receiving the edit was like watching someone off-handedly cough up a series of golden keys. I never really understood what he was talking about, but that’s why those edits were so horrible and incredible: Every time, in the process of figuring out where those keys fit and what they led to, I learned how to actually write. It’s too bad that Scocca is dead now. RIP to one of my honestly bitchiest friends.

Kate Knibbs

I remember the first time I met Scokes with remarkable clarity. Shortly after meeting up for lattes at Cafe Grumpy, we witnessed an unfathomable act of violence, and swore an oath to never speak of what we had just seen. I keep my promises, so I can’t say what we saw. But I will say that it shaped Scodawg, maybe even acted as a defining life moment. It shaped me, too.

Adam Pash

If you’ve ever deeply contemplated a subject, and you feel a certain amount of pride in yourself and the smart take you’ve arrived at on that subject, don’t share it with Tom Scocca. With rare exception, he will think more clearly about it than you ever will, if only having considered it a few moments, and it will be annoying. Tom Scocca is an asshole in possession of a clarity of thought I’d never previously witnessed, and I regret our friendship.

Hamilton Nolan

Even in a corner of the writing world dominated by media feuds, Tom Scocca stands out for the purity of his commitment to feuding. He feuds not out of personality conflict but out of a sense of righteousness, and—more than anyone I can think of—he will never, ever stop feuding, because it is a matter of right and wrong. Tom Scocca is the only top-level editor I know who once commandeered the Twitter account of a publication with hundreds of thousands of followers in order to publicly tweet-feud with random nobodies on Twitter for an entire day about some story, before control of the Twitter account was wrestled away from him.

So he’s a real fuckin’ psycho nut and I admire his clarity of purpose and pray that he always uses his powers for good and against smarm.

Alex Balk

The weather in New York on July 17th of 2012 was warm and bright: I know this because Tom Scocca reviewed it, as he would go on to do some 1,300 more times, for my now defunct website The Awl. Of everything we published over what was almost a decade there was no feature more controversial than the daily assessment of the previous day’s weather. There were a variety of responses, from bafflement to disgust to outright anger. Some people felt personally and inexplicably targeted, as if Tom were doing it specifically to irritate them. I confess to going through some of that cycle myself: amused, confused, annoyed and confused again before finally reaching acceptance. What did it for me was Tom’s facility with language, with pacing, with expression. While it was never about less than the weather, it often rose to be about much more than the weather, and almost always what came through was a kind of poetry. That’s how I prefer to think of Tom, as a poet. And not some angry guy who yells at people on Twitter relentlessly. Jesus Christ, what’s the deal there? It’s always the people who you think are better than that who disappoint you the most. Anyway, good luck with whatever it is you do next, Tom.

Emma Carmichael

When I first met Scocca I was 22 years old and writing at Deadspin, where he’d just been brought on as our managing editor. I found him really intimidating, because he gchatted in complete sentences, resembled a very tall human dandelion, and had a tendency of staring, unblinking, in conversations, which is how I imagined him reading my copy every time I sent him something to edit. I had to give myself mini-pep talks just to send him drafts, because I was so certain he would tell me it was bad. It took about five months for me to get my first positive first note on a draft out of him, when I sent him some reporting from a NBA D-League tryout. “OK, it’s good,” he wrote back. “I want to squeeze the writing a little.” I had no idea what the second part meant yet, but I almost wept with relief anyway.

Scocca is an editor who teaches in parables and lines of questioning, so if you’re not listening closely you’ll miss his work completely. I learned a lot from him in that stretch of time at Deadspin because I noticed right away that he improved everything I wrote, and I figured I should listen closely. I’m very glad I did. Seven years later, we are now the only living members of a handful of small membership clubs, including “the club of people who have been unfortunate enough to edit both Gawker and Deadspin,” “the club of people who turned down a job that Chris Jones took” (what job? you’ll have to guess), and “the club of people who believe unconditionally that I (me, Emma) could beat Tommy Craggs in a game of 1-on-1 basketball.”

And while I’m grateful for the many years I got to spend trying to decipher Scocca’s edit notes, and for our shared exclusive memberships, I’m most grateful that he brought the next great blogger into the world. It’s truly his most important work to date.

I wish Tom the best on his male modeling career. I can’t wait to see him sporting a turtleneck in the next Land’s End catalog.

Ashley Feinberg

The first time I ever worked with Tom was right before I left Gizmodo for Gawker. I’d been wanting to make the move for a while, and the condition Craggs had laid out was that I had to at least try to make it work at Gizmodo for a little longer before jumping ship. I had no intention of actually doing this, but was going through the motions to reach my desired outcome. This meant meeting with Tom to work on some features I’d been putting and that I also had no intention of ever completing. I had never spoken to Tom for any extended period of time before this, mostly because I was terrified of revealing myself as an idiot to the smartest person in the company. That single meeting was probably one of the top three most productive and rewarding experiences I’ve had with an editor. Tom instantly was able to get a sense for the scope of the stories and ask questions I would never have considered. I walked away genuinely excited about writing them, until I remembered that I didn’t really ever intend to do that and then I just felt awful.

A few years later, when Tom and I were both working on the Special Projects team and maybe a day or two before I knew I was about to quit, John announced that there would be a slight re-org and Tom was going to be my dedicated editor. I, again, had an incredible experience discussing potential stories with Tom while knowing that I would never really complete any of them.

Tom, I promise that if I am ever lucky enough to work with you again, I will not immediately quit my job.

Brendan O’Connor

Tom Scocca is the most frustrating and brilliant editor I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with. I have learned many new words from him (“dispositive”) and acquired many new opinions (“Renting a car is a GREAT way to get a crash course in how completely broken everything is in this country.”) I will most miss eavesdropping on his phone calls with his many small sons, who seem to be constantly dropping guitar picks into their guitars.

Jim Cooke

Sometimes, Tom will make a joke or reference that is so opaque I might pretend to understand but then later need to google. He makes others around him better. I’ll go to Tom with an idea that I know could be made sharper, funnier, or is missing something and he’ll know exactly what it is. I will miss him, and this place will miss him.

Kelly Stout

Tom’s reactions to stuff feel like a good litmus test for how dumb something is. In our time together, I relied on this more times than I could count. Example: one time, after another website raked me over the coals for a post I wrote, I went to Tom to tell him how much that bummed me out. I needed a pep talk from someone whose editorial judgement I respected, but also from a friend. He delivered on both in the way that really only Scocca can. I reported to him what the critics of the post were saying, and he opened with, “Oh for fucksake.” It was just what I needed, because having Tom Scocca think your critics are idiots is good assurance that you’re in the right. I respect—and endorse—no one’s list of enemies and foes as much as I respect—and endorse—Scocca’s. I hope never to be on it.

Aleksander Chan

Tom is far too generous with his wisdom. I’ve lost track of the number of times he’s saved my ass—as an editor, as a counselor, as a friend. He’s been the invisible, guiding hand behind so much of what makes working here great, and none of us can ever thank him enough.

Keenan Trotter

A few months after I first met Tom, when both of us were working at Gawker, Peter Kaplan died of cancer. This was around the same time I was beginning to realize the extent to which Kaplan, the former editor of the New York Observer, had shaped the industry I had entered, and mentored or influenced many of the writers I followed and most of the editors I either worked for or hoped to impress. But even after reading Tom’s dispatch from Kaplan’s funeral, and looking up the names I didn’t recognize, I still didn’t quite get it: What was it like to be haunted by someone like Kaplan, to hear his voice in your head as you judged your efforts against what he might have said? What was it like to watch the place you grew into yourself as a writer and reporter be dismantled, bit by bit, by a mendacious actor?

Nearly five years later—after being edited by Tom hundreds of times, and witnessing the destruction of our old company and outlet—I am closer to getting it. This industry will break your heart, over and over again. Especially if you believe, stupidly and recklessly, in anything beyond professional advancement, in the idea that journalism is not about winning awards.

Tom may be best known for his meticulous editing and argumentative combativeness, but his own writing, especially his media criticism, always left a deeper impression on me. He genuinely believed—believes!—in the possibility of a better media, and sought to bring it about. He performed open-heart surgery on stories that seemed beyond rescue, stories that went on to become the ones by which Gawker Media is most fondly remembered. Even if they despised the process, every writer he edited became a better one. And I say this as someone who has disappointed Tom more times than I can bear to count.

One of the hardest things to admit is the fact that this world could be better, that the awful things that have happened did not have to happen, and of all the people in my life who helped me become who I am, it is Tom who risked the most to remind me of this truth, day after day, so that I will never forget it.

Tommy Craggs

One problem with roasting Scocca is that he’s my favorite writer and editor, and it’s hard coming up with even lovingly barbed things to say about someone who reliably made me look better than I am. Anything I wrote that I cared about, whether it was a feature or a blog post or an email or a text, I wanted Scocca to read first. One motif of this collection, I’m guessing, is the roasters’ fear of the roastee—fear, in particular, of his exacting intelligence. The greater fear was in not having Scocca around to read your shit before other people saw it. Even now I can’t shake the feeling that these sentences are stumbling pantsless and stupid out into the world. He edited the very best of writers during his time at Gawker Media, and he edited Nick Denton, too, whenever Denton would decide to affix that battered tin bugle to his asshole and blast out another of his fanfares. Everything got better under Scocca’s hand. The vanities in your prose fell away; all the scuffling and sniveling ceased. When we were smart, some measure of it was because of Scocca; when we were dumb, it was because of Scocca that we weren’t a lot dumber. I miss working with him every day, and I wish the zombie Gawker Media Group had the first idea of how much it’s going to miss him, too.

Another problem with roasting Scocca is that he is too smart and too sane to have suffered any of the usual roastable idiot humiliations of a Gawker Media employee. The best I can come up with is that, on the day he signed his papers with Deadspin, Scocca walked facefirst into a glass wall and dripped blood all over his contract, life being much less careful with its metaphors than Scocca is with his.

John Cook

No one ever knows what the fuck Tom is talking about. Because he’s hyper-educated, yes, and over-schooled. But mainly because at some point in any substantive conversation you may have with him, he will unilaterally elect to leap forward about 120 seconds without telling you. You’re talking about whatever it is you think you’re talking about, but he sees the exchange as it’s going to unfold and just ratchets it forward, leaving you to figure out the context of where he went and how to catch up, and—if you don’t want to look like an idiot—temporarily pretending to know what the fuck he’s talking about while you do so.

The first time I experienced this was during my first real conversation with Tom, which took place in 2013 on the rooftop of Gawker Media’s old offices in lower Manhattan. It was an expansive series of wooden platforms and planters, with expensive lawn furniture five stories up above Noho. The Gawker roofdeck remains an emotionally charged space for many of us who worked for the company at the time, a potent symbol of promise and hubris and aching regret. This was in January 2013. We’d been colleagues for two years.

It wasn’t the first time we’d spoken. Tom joined the staff of Deadspin in 2011. I was a Gawker writer at the time. I’d never met him, but I knew and admired his byline, and was impressed that A.J. Daulerio’s chaotic Deadspin had drawn a real-live New York Observer alum (trust me, that used to mean something) aboard. I regarded myself as a rare Gawker grown-up (father of two at the time), and Tom was another family man, so I figured he’d be an ally.

To give you a sense of the state of company-wide collegiality in those days, Tom’s introduction to the Jezebel writer he shared a pod with upon his arrival happened via a Tumblr post in which she decried “the Deadspin writer that sits next to me now” as her “Personal Space Invader.” I recall deliberately trying to break the company’s passive-aggressive on-boarding process by introducing myself in the kitchen. He shook my hand limply and said hello.

We didn’t speak for two years.

Then we were on the rooftop. My mission was to recruit Tom from his position as managing editor of Deadspin to become my deputy at Gawker, where I had just the day before been installed as editor-in-chief. I was baffled by the whole situation, which was a function of our mutual owner Nick Denton and suddenly departed former boss A.J. Daulerio rearranging the office furniture according to some unspoken new aesthetic. I was told that I was now in charge of Gawker and that Gawker’s Emma Carmichael was to go to Deadspin in an even trade for Scocca. I have no idea if anyone bothered to ask Emma her thoughts on the arrangement, but my assignment was to sell it to Tom. Apparently his old colleagues at Slate were making a play for him at the same time.

It felt profoundly wrong and even dishonest for me to be telling this man, to whom I hadn’t spoken for two years even though we sat maybe 50 feet apart every day, how urgently I needed him by my side as I took on the role of leading Gawker. He seemed reticent, a bit confused by why any of this was happening. But the awkwardness began to fade as, together, we sketched out a shared vision of what we wanted the site to be—a pirate ship, black flag hoisted, knives at the throats of finks and phonies everywhere. We’re tossing ideas back and forth and then he just stops and says, “SMARM,” like it’s a one-word movie pitch, his eyes wide and smiling as he awaits a cheer of approval. I have no idea what the fuck he is talking about. “Sure, smarm too, all that stuff,” I mutter, trying to sound like I do.

One of Tom’s few kindnesses, to me at least, is his willingness to overlook those moments of pretending, and let you catch up without embarassment. I was supposed to have understood the years-long intellectual project he’d been gathering string on—smarm, the defining rhetorical mode of our time, the unseen ether in which criticism or analysis or argument is reframed as mean-spirited “snark.” Sure, I said. I’d love for you to write about smarm. Eleven months later, Tom pulled off what was in my view Gawker’s greatest triumph: a 10,000-word essay on smarm, headlined “On Smarm,” published on a gossip blog, that garnered nearly half a million page-views and got “smarm” trending on Twitter for an afternoon. It changed the way people thought about the internet, for the better, for a while. I giggled myself silly as our traffic- and influence-mad owner, astounded (as was I) at the prospect that a brilliantly rendered idea could light up the internet as brightly as a video of a cat being given CPR by a fireman, briefly set about re-orienting the company’s mission around the newly named snark v. smarm axis.

It was the third-best thing Tom Scocca has written: 1) being his eulogy for his father and 2) being his indictment for the murder of Gawker.

I don’t really know why we were on the roof, by the way. According to Tom, the weather that day was uninviting. “In the afternoon, up on the rooftop under a sky of rumpled gray cotton batting, it took a long time to realize that there was no acclimation to be had, and that the coolness had become an outright chill.”

I fucked Tom over. I demoted him—I told him (and myself) that it wasn’t a demotion, but it was—and named someone younger and more admired by my boss to take Tom’s place. I had reasons, but many of them weren’t mine. Tom accepted it and never, ever let me forget about it. Not in a hostile way, not in an angry or bitter way, but simply because it was something that had happened and he often found it relevant to remind me that it had. As Tom said of his father, he “saw things clearly, and he named them plainly.” It’s a comfort to know that someone will never let you get away with something. But despite my treachery, Tom has been an intense, ferocious and loyal defender of all of his colleagues, myself included. He will not stand an insult or outrage against one of his own, and he has publicly and privately defended me more times than I can count, and far more passionately than I could defend myself.

I do not believe that Tom does this out of affection. I do not believe he does it out of loyalty. He does it because he cannot bear error, and he cannot bear lies. We went through a multi-year, multi-faceted experience of profound and intense injustice together, Tom and I and our colleagues, and my capacity for rage and anger crapped out at about Month 7 of the ordeal. I came to believe that we were caught in a process against which anger was useless—and more important, I simply lacked the energy or internal courage to sustain any anger to begin with.

Tom, God bless him, rose to every occasion with a fresh supply. There was literally no insult or mischaracterization or falsehood or malefaction—in a ceaseless maelstrom of insult and mischaracterization and falsehood and malefaction—that passed beneath his capacity for outrage. I found myself saying “Let it go, concentrate on the bigger fights, what’s done is done.” But his rage sustained me. It is very easy, when the world is working its way on you, to get lost in the system that is chewing you up. Tom was a constant reminder that the world shouldn’t work this way. That the world is wrong. It is exhausting to hold that view. Tom is a marathon runner.

The closest I have ever felt to Tom was on the night that Gawker died. As I so often did over the years, I’d abandoned him (and the rest of our colleagues). I had a family vacation planned that I couldn’t get away from, and we knew what the last day of publication was going to be, so I figured it didn’t matter where I was. I was at a family cottage on the water in Edgewater, Md., not far from where Tom grew up, which is somewhere up near where the Susquehana meets the Bay—Havre de Grace? Port Deposit? Aberdeen? A modest boat ride away. It had been an emotional day of reading over Gawker eulogies in between boat rides with the kids. At the end of it, in the darkness after the games of flashlight tag ended, I waded through the mosquitoes alone down to the pier to smoke an illicit cigarette and have a drink. The moon was bright over the water, and I took a photograph and sent it to Tom, because I know he knew that kind of night on the Bay. I remember exchanging emails with him, thanking him, promising him that no matter what was going to happen that I would never fire him, and weeping at how stupid and foolhardy our little pirate ship scheme had turned out to be, how sordid and pathetic the ending. I wanted to throw that fucking phone into the water, but it was nice to know that Tom was on the other end.

The weather in Edgewater that day had been muggy and hot. In New York: “The once-dirty summer distance was clean all the way to where Sixth Avenue met the clouds. The light was bright, and even as it slipped away it left things luminous.”