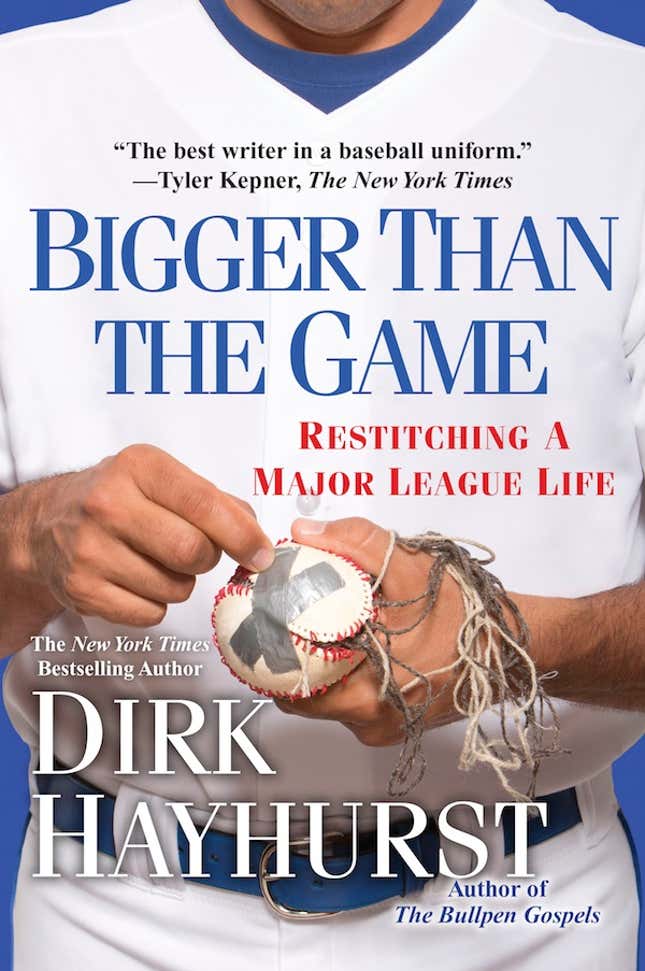

From Bigger Than The Game: Restitching a Major League Life (Kensington).

"You should go to the beach, honey," Bonnie said during one of our daily phone conversations. "Get out of that apartment. It will do you good."

"I don't really want to go to the beach," I said.

"Then go to the mall and walk around."

"Guys don't go to the mall and walk around just to go to the mall and walk around, Bonnie. Not unless they're douchebags trying to hit on underage girls, or eighty-year-old men getting their exercise."

"Then go buy yourself a PlayStation and kill something. That always makes you feel better."

"I have one at home. I'd just be wasting money if I bought another. Besides, this place doesn't have a television."

"You're making enough. Buy a television and a PlayStaion."

"Meh . . ."

"You feeling okay? It's not like you to turn down a chance at buying a television and a gaming system. For goodness sakes, you asked for it on your wedding registry and now you're not interested?" She laughed, but when I didn't follow suit, she calmed, cleared her throat, and asked, "Honey, what's wrong?"

I paced around the apartment as I talked, stopping in front of random things, like the crappy art on the wall, or curtains covering the baby-doll heads.

"I don't know," I said. "I feel crappy and I have no reason to. The last couple of days I've been having these weird feelings at the ballpark."

"What do you mean?"

"Like I'm lost."

"Are you depressed?"

"No," I snapped at her, "I'm not depressed. I'm getting paid to heal. I'm accruing big league service time. I'm pocketing the per diem. I'm a damn major leaguer, living the dream. I have no reason to be depressed."

"You can still feel depressed. You don't have to have a reason."

"I'm not depressed," I said again.

"Okay, well, tell me what else you're feeling."

"Well, these last couple days when I've come home from rehab, I get this feeling like I'm trapped in the apartment."

"Oh honey, you need to get out of that place."

"I know, but that's the strange thing, Bonnie. I get all worked up, grab my keys and head for the door and just before I open it, I stop and think about where I would go that would be fun, and nothing comes to mind. Shopping, the beach, even spending money on video games; nothing moves me."

"How long have you felt this way? When you got to spring training? After the surgery? When you got hurt?" There was a great deal of concern in her question barrage. "Honey, how long have you been feeling bad?"

I had shambled back into the bedroom and sat down on the tiny rolling desk chair and was now absently picking at one of the unicorn stickers atop the desk.

"I don't know, maybe since last year? Mostly after that fight in the locker room. I remember I felt really strange for a while after it happened. I even stopped eating and I didn't know why."

"Wait. Stop. You've been feeling bad since last year?"

I got a piece of the unicorn up, but it tore and left me with half a paper head.

"Not bad, just not good. But, you know, I just chalked it up to writing the book and all the stress of being in the big leagues. It wasn't a big deal."

"You stopped eating. That's a big deal."

"I was still pitching well, and I got the book done."

"That doesn't matter! Why didn't you say something?" I flicked the half head from my fingers and put my head down on the table top, the phone sandwiched between my head and the desk. "Honey, why are you yelling at me?" I asked. Then, jerking up, "Wait. Have I been, uh, you know, less of a man in the bedroom? Oh God, I heard that can happen. When you're feeling weird it's like your mind has a link to your . . . Oh God. Bonnie, be honest, has my not feeling good somehow impacted my male potency and you just weren't telling me?"

"What? No! No, your potency is perfectly potent. I'm just really concerned. You really should tell someone how you're feeling before you stop eating again, or worse."

"Who do I tell that to, exactly? And what do I say when I do it? Do I walk up to Alex and say, 'Hey Al, I know there are a million guys in the minors who would love to have my job and that I'm making big-time money to be here, money you didn't have to give me, but I'm feeling really sad and I don't know why. It's probably nothing, but my wife told me to talk to you about it. Side note, she's worried about my performance in the bedroom."

"I am not! Will you stop with that? Honey, if you can't talk to Alex, then talk to the other guys on the team about it."

"Oh my god, I absolutely can't do that." I was standing now and waving my arms in the air, like I was trying to prevent a plane from landing.

"Why?"

"You can tell your teammates a lot of things. That you're angry, that you want to get drunk until you can't see straight, that you need them to keep a secret about you cheating on your girlfriend. But you just cannot talk about your emotions. I told you what happened when I did that before I started writing, remember? Baseball players don't do that."

"Why?"

"Because, think of what it sounds like, Bonnie: weakness and whining. A guy is making more money in one night than most of the population is making in two weeks while playing a game for a living and he's sad inside; boo-hoo. And do you think guys on the team are going to feel bad for me? Me, after what I've done? You think coaches are going to tell me, 'It's okay son, you don't have to be mentally tough to do this job'? Hell no!

"Look," I continued, scaling the bed and flopping into the hole in the mattress, "you work with special-needs children for a living. You know people look at mental issues differently. Remember when your client, Ian, had that freak-out, screaming and hitting himself because he was overstimulated and the secretary burst into your office and threatened to call the cops on him if you didn't get him under control because she was afraid?"

"Yes," Bonnie said.

"She didn't understand that child had an issue. I know the team wouldn't understand if I say I'm having an issue. I've seen it happen before and it changes the way people think about you. Furthermore, I don't even know if I'm having an issue! We're just talking about feelings right now, is all. We're just talking about feelings. I'm not talented enough to stay in this game if I'm going to write, be injury-prone, and get labeled as a head case."

"But there has to be someone you can talk to about it. You can't be the first person in the big leagues to deal with stuff."

"We have a team psychological doctor, and if worse comes to worst I can talk to him."

"You should talk to him now. Why wait?"

"Because I can handle this. I'm just being a little irrational right now. This is a new routine. I recognize it, and if I can recognize it I can control it. It's fine. I'm fine. We're fine. Okay?"

It took her awhile, but finally she said, "Alright. But what are you going to do to deal with it on your own?"

"I have a technique that's worked for me before. Don't worry, honey. I'm a professional, remember?"

I shook the bottles of oxycodone and sleeping pills like maracas, then sat them on the kitchen counter and opened the refrigerator. A twenty-four pack of Yuengling lager stared back at me. I pulled one of the cold, sweaty green bottles out of the box and popped the cap off. Then I shook out a pair of sleeping pills from its bottle and swallowed them with a swig of Pennsylvania's finest suds.

I'd been feeling things I didn't understand, but I decided that I didn't have to understand them. I just had to turn them off. The sleeping pills made it all go away. Without them I'd get home around noon, fiddle with the Internet, panic about how I was wasting my day, get in the car, go nowhere, get out of the car, go back into the apartment, hate myself, feel strangely emotional, hate myself some more, call Bonnie, tell her everything was fine, then lie in bed for a few hours, wondering why I couldn't sleep. With the pills it was clean, simple, easy. I'd pop a few after my rehab, go to sleep and wake up around six a.m.—after fourteen or so hours of sleep—rested and ready to face a day of pink weights and social isolation.

By early March, however, I was taking a trio of pills every afternoon, along with several beers. I didn't think anything of it, honestly. Normal tolerance building. It was similar to how I made it through my first year with the Blue Jays. I learned it from watching other guys on the team. I believed that I just needed to ride out whatever it was that was making me feel down . . . and that I shouldn't have felt down in the first place, since I was making such great money and would have my job all year.

Because I didn't have the cross-country-flights-screw-up-my-sleep excuse to get more sleeping pills should my supply run out, I started mixing in the oxycodone (which also made me drowsy), or more alcohol, or both. I never turned to hard liquor because that sounded like something a guy who had a problem would do, and I did not have a problem. I just liked sleeping.

I rationed out the pills to make sure they'd last, stocked up on beer, and made sure not to spend too much time at the park, where I often felt isolated in the training room, inadequate because of my injury, and angry because of Brice. As long as my routine didn't change, I'd make it through spring training by hitting my internal snooze button repeatedly. I projected that I'd run out of pills just after spring training, by which time I'd be throwing again and Brice would be gone. That, I believed, would make all the difference in whatever was bothering me.

Of course, this was all based on the assumption that things wouldn't get worse.

One afternoon, after my pink weight lifting came to a close, I sat slumped and weary on my blue training table with an ice pack lashed to my shoulder by a tan bandage roll. A white plastic digital timer was clipped into the folds of the bandage with an alarm set for twenty minutes, which had long since run out. The water from the pack was expanding across my workout shirt in a damp, gray splotch, and trickling down my arm to my elbow, where it beaded and dripped onto the floor below.

The training-room doors shot open and in flew a flock of Blue Jay pitchers, squawking and chirping as they came. They were the first of the bullpen throwers and, throwing routines now finished, they'd come in to do their arm maintenance program. Brad Mills, a talented, left-handed pitching prospect and friend, was among them. He requested a pair of ice packs, which a trainer lashed to his arm with a tan elastic bandage, and then he sat down next to me.

"How's it going in here?" he asked.

I blew out a sigh. "Living the dream. How about you?"

"Same old. Work on drills we use once a year, then throw a bullpen."

"Sounds heavenly. How'd your pen go?"

"Good, I guess." He shrugged, but only his unwrapped shoulder moved.

"You guess?"

"They want me to work on a slider, or a cutter, something with that cross-plate action." He shook his head. "Thing is, I don't want to add something that I'm not confident in, then spend all spring training getting beat on a hunch they have. You know how often you hear that, right? Guy comes into camp, coaches all want him to learn something new, player does his best to please them, gets his ass kicked, then spends the whole year in Triple-A because he wasn't true to himself."

"Work on it while they're watching, then do what you want in games," I said.

"What if they ask if I'm throwing it?"

"Say you are. Have your catcher say you threw a couple good strikes with it. Then, so as not to be obvious, have him say"—I raised my left arm and made quotes—"'it's got the spin, it wants to break,' or something. You won't be the first guy who bullshitted your way through a new pitch."

Mills nodded, and smiled.

"Did they call you this off-season and tell you what they expected from you?" I asked. Mills was talented, no doubt about it, but the brass was right, he did need a cutter or slider. I wondered what else they thought of him.

"Alex said that I had a future with the club," Mills said. "That older guys were getting more expensive and that I would get my chances. He also said that I'd probably see some action in the same capacity that I did last year but, you know, anything could change in spring training."

I turned and stared at him. He'd just repeated everything Alex had said to me before my injury, almost verbatim.

Mills furrowed his brow. "What's wrong?"

Instead of answering, I opted to slump further down the Blue Jay color-coordinated wall.

I actually believed I was unique to the club and would become one of its future contributors. But there were dozens of guys just like me in this organization, with the only major difference being none of them were stupid enough to run out and get themselves injured. I was an idiot. A stupid, broken idiot.

"You think I should scrap the slider, then?" asked Mills.

"No," I said, "it's not that. You definitely should try the slider. It's just that—"

"Media." The voice rang from my left, opposite Mills. We both turned to regard "Brice Jared" standing with his hands on his hips, lip curled in a wry smile. When my eyes locked with his, he spoke again. "What's up, Media?"

"Brice," I said flatly. "Something I can do for you?"

"Nah, man," he snorted. "I'm great."

I said nothing.

"Saw you making friends with the reporters," continued Brice, loudly to make sure others could hear. "What is it, like three weeks into camp and you're already sucking off the media again?" He was referring to me talking with the gaggle of beat reporters that could always be found in the locker room when the team was there. They were my best chance at getting my book on the public's radar now that I was busted. I had to talk with them, beg them for some plugs.

"I wasn't talking to them about you, Brice, don't worry."

"You're making guys uncomfortable again."

"You're the one that's stirring shit up again. I've met some of your friends."

Brice shook his head. "Me? I didn't do shit. You do it to yourself. I really thought"—he put up two fingers for a trainer inquiring about ice packs—"that after last season you would have learned your lesson."

"I was kinda thinking the same thing about you."

"So that's it, huh?" He seemed offended, as if the conversation had only now become personal. "You gonna spend all of this year pissing this team off, too?"

"Don't go telling people bullshit like you did last year, and I'll bet no one will care."

"Someone's gotta warn them about the shit you're up to."

"And what is that? I didn't do a goddamn—" I stowed my anger when the trainer who'd made Brice's ice bags came to wrap him. I at least had good enough sense not pick a fight in front of the training staff. When the trainer got done strapping the ice on Brice, he gave it a few choice whacks to shape it to Brice's shoulder and elbow, then clipped a timer onto him and walked away.

"Thanks, Frosty," said Brice. Then he looked back to me and said, "Well, I'm sorry about your injury, but karma's a bitch, ain't it?" He shrugged and walked away, leaving me furious, but unable to think of anything fast enough to win the exchange.

"Good to see you guys are still friends," Mills said as Brice walked out.

"Oh, we're tight."

"You know, if I were you, I'd keep writing just to piss him off."

"If you were me? Shit, you're afraid of not doing something the coaches want you to do because you don't want to make them think you're un-coachable."

"That's different," Mills said. "We're talking about what a player thinks versus what management thinks."

"You think management isn't weary of me? Please. You have no idea the trouble that fucker got me into last year. I'm a liability now. Thank God Alex likes me or . . . Well, lets just say some of the guys on this team think I'm a time bomb. It's only three weeks into spring training, but if this keeps up I'm not going to have a job when I'm healthy." I stood up and pulled the end of the bandage free and began unraveling it. "Let me ask you something: If you'd come up to the big leagues last year and dominated, do you think they'd be asking you to throw a slider right now?"

"No, probably not," said Mills.

"Of course not. Hell, they'd probably be asking you what your secret was, so they could teach it to minors boys." I let the ice pack fall to the ground. "Success always makes right up here. I can't pitch right now, so I can't afford to piss anyone off. If that asshole keeps playing well and telling guys I'm sneaking around with microphones in my pants and feeding inside scoops to the media, my life will become hell. I'd be better off gone."

"I don't know if it's that serious."

"It's that serious," I said. I threw my soaking wrap and towels into a laundry bin. "In the meantime, I play the social game. I've got to. There will never be a day when I get to round everyone up and have a press conference to address the issue and we all talk about it like civilized men. That's not how baseball works."

"It's a funny game," offered Mills.

"Oh, it's real funny. So why aren't more people laughing?"

"I thought you couldn't demote a player if they're injured on the big league roster," I said, standing before George Poulis in his little square office, holding an official Blue Jays memo in my hands. "Am I getting sent to the minors? Is that what this means?"

"No, no, no. That's where we do all the rehab assignments," George said. "It's not a demotion, just standard practice this time of year."

"But why wouldn't we just stay here? I mean, there is going to be like a million bodies over there." And there would be, since minor league camp is about five times the size of big league camp.

"You'll do your rehab when the minor leaguers are out on the field. Don't worry, we have Jep Jasper working over there and he's a really good guy. He'll take great care of you."

But I didn't want to be taken care of by a really good guy. I wanted to stay in big league camp. Over on the minor league side, there were no more five-star breakfasts. No more catered lunches. No more on-demand clubby service. No more extra-wide custom lockers. And no more access to the book-selling, joke-sharing, big league media crew. I already didn't feel very connected to the team, it's true, but getting sent to the minors was like getting unplugged altogether and thrown out of Neverland at the same time.

"I'm sorry," said George, "but you'll adjust. You can come to camp later, sleep in, go out and get breakfast. And of course you're still welcome to come over here after your treatment, you know, and hang out with all your friends."

"Right," I said, defeated. "All my friends. Of course."

"And we still get all your reports, so we know right where you're at."

"Great," I said.

"Great," George said. "You'll start reporting there tomorrow."

Outside George's training room office I wadded up the memo and threw it in the trash. At my locker, my Blue Jay-logoed equipment bag was already open and partially packed. Being on the big league side of the operation meant that the clubhouse staff knew everything you needed before you did. Usually it's a perk. This time it felt like a nail in my coffin.

A question from behind me: "Media, you leaving us?"

It was Brice. I knew the voice, but I did not turn to face it. "All the rehabbers are going over to the minor league side. Happens every year," I said, reaching into my locker's cubby to grab a protein-shaker bottle I'd brought with me.

"Oh, I know, but those guys will probably be coming back," Brice said.

"What's that supposed to mean?"

"Things are changing around here, man. Some good arms in camp, that's all."

"You don't think I can make it back to the bigs?"

"I don't think you can make it back to the bigs here," he said.

"You're an asshole," I said.

"Man, I'm just trying to be real with you. I told you way back in the day the shit you was doing was going to catch up with you. You didn't listen. Now things are changing around here and I don't think there's gonna be room for guys who don't listen."

"I'll be back, pal. Don't worry about me," I said.

"Media, I don't worry about you. But some of the others guys around here do. That's the problem. People talking about you, bro. People talking and it ain't good."

I wadded up my sweatshirt and slammed it into my travel bag, then turned to face Brice. "And what are those people saying? Huh? Funny how you're always around when people are saying stuff about me."

"I don't go looking for it, man." He held his hands wide.

"Yeah," I said, "but you always seem to find it."

"I guess you're just a popular topic," he said. "Kinda funny how popular you are, being hurt and all. I mean, it's like you wanna be hurt. It's like you don't care about the team no more. You just care about selling books. It looks shady, man."

"And that's what everyone thinks, huh? That I got hurt so I could sell books? Are you a fucking idiot? Do you even understand how—"

"See, there you go again. You're so smart and we're so stupid. You don't listen, man. You don't fucking listen. You can't take criticism, that's your biggest problem, that's why guys don't like you."

"What the fuck are you talking—"

"If I was you," Brice interrupted again, "I'd drag your injury out, man, play that Club Med card and collect everything you can. 'Cause I keep hearing things, you know?" He buzzed his finger around his head as if the voices were coming from secret sources.

"I don't give a shit what you hear."

"We both know that ain't true," he said.

"Why don't you get the fuck out of here and leave me alone?"

"Why? This is my clubhouse. Yours is on the other side of town."

I should have torn into him. Left big league camp with "knuckle contusion" added to my injury report. Instead, I felt like I was about to unravel. My emotions were wrong, busted, scrambled. Rather than focused, directed anger, the kind I had summoned in previous encounters with Brice, the kind that helped me get through tough jams on a baseball field, the kind that made me a ball player, what came coursing through me was raw, unchecked, emotional overflow. I felt my face flush and my eyes start to burn. I was going to cry!

I had to get out of there before it happened. I turned away from Brice, grabbed my bag and zipped it. Brice just stood there, watching me.

"Go fuck yourself," I said, heading for the door.

"'Bye."

I had to head back over to the major league side of camp for a mandatory security meeting. By this point in camp, some cuts had been made and the team was starting to bond, forming a sense of who was going to stick around and who was heading to Triple-A. In many ways, I was cut, and my presence around the club was like that of an outsider—like someone who gets kicked off a reality television show contest but then gets invited back for a reunion.

I sat in the back of the classroom, silent, listening to the guys joke and mock each other. Most of them had relationships off the field. In fact, they'd held a party in my absence that they referred to as their Boats and Hoes party, wherein players rented a boat, invited a ton of girls, dressed in yuppie New England boat apparel, and got obscenely drunk. Some of the guys I was rehabbing with were there. I had no idea until now.

The meeting was conducted by ex-law-enforcement officers. Their job was to cover all the pitfalls of the modern athlete's life. They warned us about things like getting your picture taken on cell phones in a bar, drinking and driving, and how, if you own a gun and beat your wife, statistics say she'll use the gun against you—which can be very bad for your career.

One of the guys asked, on behalf of another guy of course, if it was also true for the beating of boyfriends. The answer was still yes. Then a PowerPoint slideshow was done with a half-naked woman mixed in every three slides. Then some advice was given about what to do if a woman was stalking you. Then a volunteer was selected to wear beer goggles and play catch. It was a very comprehensive meeting.

At the end we were asked to sign a sheet saying we'd attended. Then we were given laminated cards with MLB security numbers on them that we could call if we, or anyone we cared about, were in danger as a result of the public nature of our job. I wondered if I should tell them that just about every night I was taking enough pills to wreck a car should I ever decide to leave the apartment and drive. After the beer goggles went on, however, and the jokes about guys beating their gay boyfriends, I decided this wasn't the time or place for that.

I took the card, signed the sheet, and thanked them for the show.

Before I left to head back to the minor league side of things, I made sure to hit up the big league breakfast spread. It was so good to see it again. I loaded up a plate and sat at an unoccupied table. The cafeteria was nearly empty by this point, since most of the guys had already eaten and were getting ready to take the field. I sat alone, eating and reading the latest USA Today until a group of relief pitchers came in for a cup of coffee and stopped talking when they saw me. I pretended not to notice, and kept my eyes trained on the paper, though I'd stopped reading, ears open.

One of the pitchers was Brice. The other was number 77. There were two others in the entourage and they all poured themselves one cup each, then took an extra empty cup so they could air-cool the coffee to a drinkable temperature by pouring the contents of the cup back and forth from one to the other. I knew the other two players in the group and yet, it was as if I did not know them. They were fellow relief pitchers with maybe three years of big league time between them. We'd been teammates at one point or another but not for long, and we were never close.

Stoically sifting their coffee, they filtered out of the room save for one player, "Jeremy Kitsch," who came over and stood in front of me at my table with his glove sitting atop his head like the butt of an acorn. He poured his coffee back and forth, steam rising from the white Styrofoam after each flushing.

"Hey dude, how are you?" I asked, looking up from my paper as if I'd just noticed him.

"Hey, man," he said evenly.

I watched him pour, waiting for him to speak. There was something he wanted to say, but it seemed like he was weighing the thought, passing it back and forth like he did the coffee.

"Hey, man," Kitsch said again. "You think you could maybe take it easy with the media?"

"What do you mean?" I sat back in my chair.

"Well, you haven't been over here for a while, and the first thing you do when you get here is whore out to the media. It just looks bad, you know?"

When I'd come over to the big league side of camp that day, before the meeting started, I caught up with the media. They were in a scrum, pressed around the lone locker-room television, watching updates and highlights from around the league. I elbowed in, said hello, shot the breeze, asked them if they could plug my book, which would be out soon. If I was to make a run for any bestseller lists, I'd need their help.

"I was just trying to get some book pub, man. It wasn't like I was talking about you guys or anything. It wasn't any big deal."

Kitsch looked down at his coffee. "Nah, man," he said. "It's like, we're here trying to do our jobs and it's like you're here focusing on the media. It's like every time we turn around you're gushing about your book and that you're a writer and it's taking attention away from the team, and that's not right."

"It's not like that," I said.

"Maybe, but that's what it looks like."

"Well, it may look like that, but that's not what is going on here. The media is like free advertising, you know. Besides, I'm hurt, and on the other side of camp. I'm just trying to make the most of my opportunities."

"I understand, man. I think most guys know what you're trying to do, but I also think most guys think you're going about it the wrong way."

"What other way should I be going about it?"

Kitsch shrugged.

"Hey," I said, "Kevin Millar and his Cowboy Up bullshit were paraded around this locker room all last year and no one said anything to him."

"That's different."

"How so?"

"Millar's got his ten years in the Show. He can do what he wants, man." He made his final pour and placed the full cup into the hollow cavity of the empty one. "Look," he said, "it's just that, you don't have a lot of time and you're hurt. You're in there"—he gestured to the locker room—"whoring out to the media, joking around with them and it's like you're just using this to get a paycheck and sell books while some guys are in there dying to have what you have."

"You think I hurt myself so I could pull a Club Med and sell books?"

"I'm just saying . . ." Kitsch shrugged again.

"No, you're not just saying. You're accusing. You keep telling me what this looks like, you say you understand me, but you also want me to stop because it looks wrong. I don't get it."

Kitsch shrugged. "I guess it's not fair, man, but you know how it is. It's baseball. You could be right, but if the whole group thinks you're wrong, then you have to respect the group."

I said nothing. I looked down at my paper, furious at the flawed logic and yet knowing full well in this context it was law. I couldn't believe I was being accused of pulling a Club Med, what with all the pills I was taking just to endure the experience. I wanted to tell him, I wanted him to know exactly what the fuck I was dealing with just to have the opportunity to deal with it. But my face was hot and my heart was pumping. I looked around the room for all the exits, should I need to get up and run, and there, just outside in the hall, I could see Brice and 77 holding their coffee, quiet and watching me out of the corner of their eyes.

"What"—I coughed to make it seem like I was choking— "What do you want me to do?" I asked.

"Be more discreet. Guys think you don't respect the locker room. You're not even supposed to be here today and when you do show up it's like all you want to do is talk to the media. I mean, think of how it looks to them. Just have some respect."

"Not supposed to be here?" I shook my head. "If you all know it's not me trying to disrespect you, why does everyone feel this way?"

"That's how it is. Guys don't like it, so you have to decide if you want to respect them or not."

Despite my best efforts, Kitsch must have noticed my emotional state by this point. His tone changed, but the insult didn't. "Hey man, I know you gotta sell your books, but take the media outside with you or something. You know, where no one can see you talking to them. And maybe don't be talking about your book all the time. Talk about the team or something. Talk about the game."

"But I've been sent to minor league camp. I don't know what's going on with the team," I said, my voice uneven.

Kitsch shrugged again. "I'm just trying to help you out is all."

"Thanks," I said, now hunched over the newspaper.

"Yeah man, anytime."

From Bigger Than The Game: Restitching a Major League Life by Dirk Hayhurst. Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved. Reprinted by arrangement with Kensington Publishing Corp.

Image by Sam Woolley.