If you love American music, it’s more than likely that in 2016 your favorite songwriter either published a bestselling memoir, died, or won a long-shot Nobel prize. This means that you probably read a greater-than-average number of essays and considerations about songwriting itself, and about some of the biggest extra-musical questions surrounding it: Can songs be literature? Is country music inherently conservative or radical? How do lyrics and artistic personae inspire generations of sociopolitical change?

The year was so full of gleaming, deserved paeans to legendary songwriters that it went basically unnoticed when Smokey Robinson received the annual Gershwin Prize for Popular Song at a D.C. gala concert less than 10 days after the presidential election. This is only fair; the Gershwin Prize is a perfunctory award from the Library of Congress for wealthy musicians who are already buried in accolades. (Previous winners include Billy Joel, Stevie Wonder, and Paul McCartney.) The ceremony, which for Robinson was hosted by Samuel L. Jackson and debuts on PBS tonight, is essentially a chance, like the White House Correspondents’ Dinner or—theoretically—inaugural balls, for professional Washington to buy a night of Hollywood glamour with federal prestige.

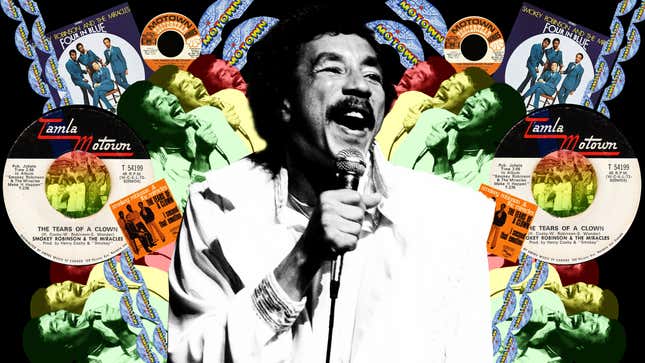

Still, the bestowal of a silly award is a chance for retrospection, and given all the hosannas sung for various heroes over the last 14 months, it is past time for someone to say what should go without saying: Smokey Robinson is the greatest American songwriter.

I find it shocking that anyone would argue otherwise, though surely some will. Funny as it sounds, Smokey Robinson has always been a little overlooked. Everybody loves his songs, but few people are his devotees. Unlike Motown peers like Wonder or Marvin Gaye, he is not often credited with a full-blown masterpiece LP. (A particular oversight, seeing as he’s released at least two.) With his high tenor, 50-year baby face, and steadfast focus on pleading romantic ballads, he’s never been terribly cool—there were always other artists, at Motown and elsewhere, who were more groundbreaking, soul-bearing, poetic, or any of the other descriptors we use to discuss serious songwriting achievement. He somehow even avoided winning a Grammy until 1988, and that award perversely came for a song he didn’t even write. For many people, especially non-black people, Smokey Robinson is best known for giving the world the high points of wedding receptions and oldies stations.

Even if this was true—if he had merely composed a half-dozen songs, like “You Really Got a Hold On Me,” “My Girl,” and “My Guy,” that most human beings could recite in their sleep—that should grant him immortality. But for a time, especially in his earliest years, he was considered more than a confectioner. In 1968, the height of artistic and socially relevant pop music, Rolling Stone opened a profile of Robinson by declaring he was “the reigning genius of Top 40.” Robinson was a decade into his career as an artist and vice-mogul of Motown, and the concept of album-length statements was still new enough that his talent for the three-minute form could be admired for the awe-inspiring gift that it was.

“Since the Beatles and the Beach Boys dropped out of the single-then-follow-up-album pattern aimed at the AM teenage listener, William ‘Smokey’ Robinson has had the field to himself,” wrote reporter Michael Lydon.

The rest of the piece focuses on his craftsmanship—not his vocal prowess, lyrical themes, or numerical chart success, but his shocking facility with pop structure. “By now Smokey doesn’t know how many songs he’s written. Some never made it, but there have been dozens of hits, each in its own way perfect. There’s no formula, but all have a certain liquidity, a subtle and simple elegance. Smokey makes it look easy. There is a strong beat, a sure bass, and then a seductively harmonized melody whose turns are exactly matched by the lyric’s mood.”

Lydon repeats the old anecdote that Bob Dylan once referred to Robinson as “America’s greatest living poet,” a line I find even more poignant now that Dylan has immersed himself, at the very moment of his Nobel crowning, in the classics of Tin Pan Alley. (He recently announced his third straight record of Sinatra-era big-band standbys, this one a triple album.) But back in the ‘60s, in the beating heart of Motown’s infamously factory-like creative setting, Smokey Robinson was the one whose work already read like Cole Porter:

You’ve got a smile so bright, you know you could have been a candle

I’m holding you so tight, you know you could have been a handle

The way you swept me off my feet, you know you could have been a broom

The way you smell so sweet, you know you could have been some perfume

From the start, Robinson mastered the virtues of the Great American Songbook and its down-home cousin, the country standards: His songs were linguistically clever, emotionally direct, melodically indelible, and never overlong. By marrying these elements to a finger-snapping beat, he and Berry Gordy essentially created modern pop music as we know it. The Swedish Academy credited Dylan with “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,” which is fair enough, but Smokey Robinson perfected that tradition, and updated it for the era of black-led pop.

“Shop Around,” one of his earliest hits, recorded in 1960, is just about the oldest music that still sounds halfway contemporary to 21st-century ears. Go back even one year to his very first Motown song, “Bad Girl,” and its doo-wop-by-numbers sounds like time-capsule shorthand for pre-Kennedy innocence. But “Shop Around” is bluesier and more rhythmically persistent. It sounds more like James Brown than The Flamingos, which means in 1960, it sounded like the future.

From there, the nonstop Hitsville approach sharpened Robinson’s instincts. The unwavering focus on radio-ready romance seemed to free him, as if, like a businessman who owns 10 of the same suit, he never had to think about what to wear in the morning. Every song was about L-U-V, and he found an apparently limitless number of metaphors for it: emotional connection, poverty, hunting, optical illusions, black-tie parties, illness, treacherous driving conditions. Occasionally, as in “My Girl” or “What Love Has Joined Together,” his songs were just litanies of different metaphors strung together with a chorus:

It would be easier to take the wet from water or the dry from sand

Than for anyone to try to separate us or stop us from holding hands …

It would be easier to take the cold from the snow or the heat from fire

Than for anyone to take my love from you ‘cause you’re my heart’s desire …

It would be easier to change all the seasons of the year

Than for anyone to change the way I feel about you; I love you dear

I don’t care whether these lyrics constitute poetry or literature; they are songs, and the way they sit inside a melody lends them meaning and effectiveness. In the case of “What Love Has Joined Together,” at least in the Temptations’ most famous version, the verses above are sung as staccato, repetitive beats that give way to a plaintive, pained, “I love you/ I love you from the bottom of my heart” in the bridge and then a soaring, grateful croon of the title phrase in the chorus. The emotion, as always, is tied to the movement of the words.

That’s why it’s surprising how wordy he could be. He found some pretty roundabout ways of saying his heart went pitter-patter. Take “Legend in its Own Time,” a 1969 chunk of explosive orchestral soul and one of the great forgotten songs of the first Motown era:

In the past there have many loves many men have written about,

But by the time those loves were recognized,

By the time somebody realized,

Most of them had gone and faded on.

But this love that I’m pledging will surely be a legend in its own time.

Forget about romance. Smokey Robinson was trying to make history, and this is why he’s the greatest. His songs weren’t about running around with girls, they were about finding the deepest possible satisfaction in life, a quest that left him vulnerable to the deepest miseries as well. His great subject wasn’t really love—it was devotion. He could stick around until you loved him:

Oh, you may not love me now but I’m stayin’ around

‘Cause you want my company

Just like push can turn to shove, like can turn to love

And it’s my philosophy that

If you can want, you can need

And if you can need, you can care

If you can care, you can love

When you want me I’ll be there

He’d even stick around if you didn’t like him:

Honey, you do me wrong but still I’m crazy about you

Stay away too long and I can’t do without you

Every chance you get you seem to hurt me more and more

But each hurt makes my love stronger than before

I know flowers go through rain

But how can love go through pain?

On the first-ever Motown hit, “Way Over There,” he pledged an early version of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”:

I’ve got a lover way over there on the mountain side

And I know that’s where I should be

Don’t you know

I’ve got a lover way over there across the river wide

I can hear her calling to me

Oh, she’s calling my name

So sweet so plain, I can hear her saying,

“Come to me, baby.”

I’m on my way

And then of course there is the song that crushes all others, his “Born to Run” or “Mama Tried” or “Like a Rolling Stone,” only it’s better than all of them. I refer, of course, to “Tracks of My Tears.”

Sadder than any country song, more beautiful than any jazz ballad, and more vulnerable than just about anything you can dance to, not even The Big Chill can undermine this fire:

Outside I’m masquerading

Inside my hope is fading

Just a clown oh yeah

Since you put me down

My smile is my makeup

I wear since my breakup with you

I won’t be watching the broadcast of Smokey Robinson’s Library of Congress concert, since we all already know what it will be: overwrought guest stars and a charmlessly professional backing band, interspersed with celebrity testimonials that will gloss over fascinating detours like his 1973 show of solidarity between black and Native Americans, “Just My Soul Responding.” (They also won’t mention his penchant for album-padding schmaltzy cover songs.) Smokey will be there with the same “I love everybody!” grin that he’s had since his teens. He’s still not cool, but no one in the last 60 years has repeatedly smuggled more poetic grace and emotional power into two verses, three choruses, and a bridge. They shouldn’t just give him the Gershwin prize, they should name it after him.

John Lingan is writing a book for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt about the last honky-tonk in the Virginias. He lives in Maryland, and is on Twitter.