There were few thrills in preadolescent life as dependable as the voice of Troy McClure. That first resoundingly confident "Hi!" triggered a Pavlovian response like no other single syllable: Here, without a doubt, comes a belly laugh.

Half the time, I laughed without knowing what the joke was. McClure's prolific fictional career included "such films as" Gladys the Groovy Mule, Son of Sanford and Son, They Came to Burgle Carnegie Hall, Man vs. Nature: The Road to Victory, Alice Doesn't Live Anymore, and Today We Kill, Tomorrow We Die. When I was 10 or 11, these were all gibberish to me. It would be years before I understood exactly what kind of person McClure was even supposed to be spoofing. So why was he so funny?

For one, there was the base absurdity of him, this man with the infinite filmography who still needed to jog viewers' memories. There was his ceaseless optimism, his willingness to tape one more patently worthless spokesman job after a lifetime of forgettable crap. And of course there was that voice, a sonorous, practiced baritone that was often heard through hazy reel-to-reel classroom audio or the tinny speakers of the Simpsons' own TV. Troy McClure was a total pro, happy to tell you about a telethon, a slaughterhouse, a circus, an airport, bear attacks, or seatbelt safety, and all with the same insistent "What? And leave showbiz?" enthusiasm. He made nothing but garbage, and was always happy to share it with an audience. Even a suburban kid with no cultural knowledge beyond The Simpsons could recognize the humor—and the truth—in that.

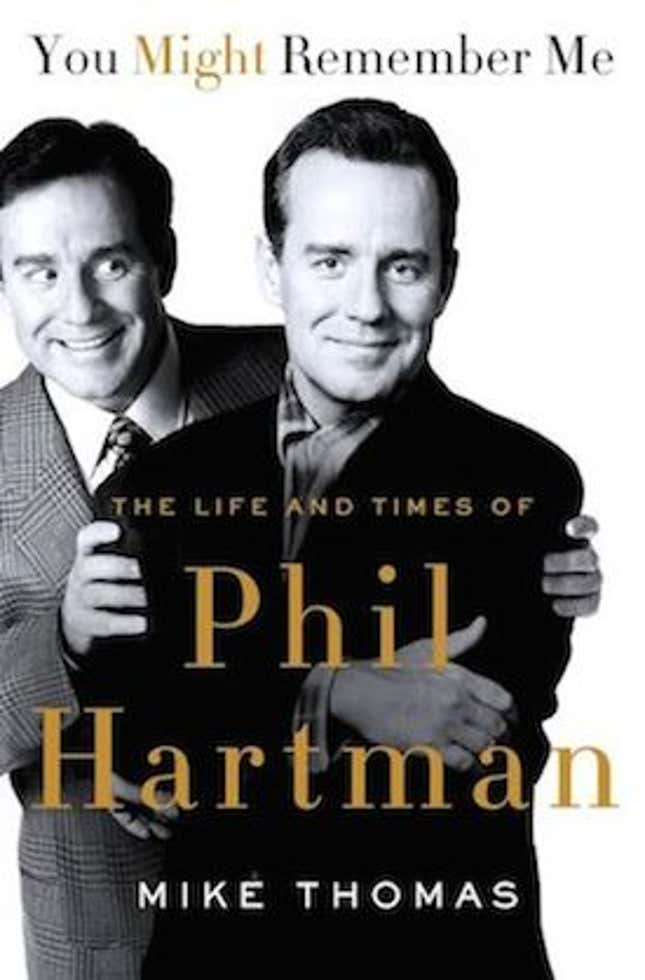

For 12 years, from his debut on Saturday Night Live in 1986 to his awful death in 1998, Phil Hartman—the voice of Troy McClure, and one of the most prolific guest stars in Simpsons history—lived in that zone where shamelessness and pride meet and amplify each other. Mike Thomas's scrupulously researched (and perfectly titled) new biography, You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman, is the first book-length attempt to understand just how a guy who made smug unlikeability a stock in trade was so beloved for so long. (In Grantland's recent SNL cast bracket, he made it to the Finals, bested only by Will Ferrell.) Unlike his colleagues Dana Carvey, Mike Myers, Adam Sandler, or Chris Farley, he never had a breakout role, but he played such a broad gallery of hucksters, shysters, and frozen-grinned lugs that he certainly owned a type.

The classic Hartman character is all too happy to tell you how successful he is, and all too oblivious to how pathetic he sounds. He's often some kind of performer, someone who knows how to keep up a façade in front of an audience or a camera; the entire joke of, say, Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer is that he's actually a fine lawyer—eloquent, logical, and convincing. More often than not, he played pitchmen like McClure, unlikeable dunces perfectly attuned to the by-numbers ad copy for Colon Blow or a torrent of mechanical gibberish. He may not have had a "Living in a van down by the river!" or a "Schwing!", but for a too-brief time, Phil Hartman was the Caruso of American bullshit.

As Thomas's book makes clear , nothing about Hartman's early life pointed to that fate. Born Philip Edward Hartmann in 1948 (he dropped the second N for show business), he grew up in Brantford, Ont., less than rich but ensconced in a mid-century suburban idyll of unlocked doors, a traveling-salesman father, a mom named Doris, BB gun misadventures among his seven siblings, and Latin mass every Sunday. When he was 10, his father moved the family to the Los Angeles suburbs, first to Garden Grove and eventually to Westchester, where Phil took up surfing and grew to love the outdoors.

Hartman started his show-business career by doing illustrations for his older brother's music-management company, including album covers for America, Poco, Steely Dan, and other clients; his most famous creation of this period was the Celtic-knot logo for Crosby, Stills and Nash. By the time he joined L.A.'s famed improv group the Groundlings in 1981, he was a financially stable professional in a company of starving artists. When he left five years later to take the job at SNL, he was 38 years old, the relative old man in a company of hungry, scene-chewing young talents like Carvey and Myers.

Thomas insightfully notes that Hartman's own creations tended to be throwback-Hollywood types, particularly his lifelong favorite character Chick Hazard, a hardboiled '40s-style detective. Many of the more recognizable faces he adopted—Sinatra, Reagan, Charlton Heston—were relics as well. This is how Hartman honed that razor-sharp vocal facility: His obsession with classic Tinseltown staccato dialogue gave every line-reading a sense of timelessness, like he just emerged from the background of His Girl Friday or Double Indemnity. Even in a contemporary guise, Hartman always seemed out of time. And that's because his essential character, the slick untrustworthy dunce, is indeed a national archetype.

Constance Rourke opened her 1931 study American Humor: A Study of the National Character with a depiction of an 18th-century Yankee housewares trader skipping gleefully through the South, selling pots and pans to skeptical rural villagers. Equally ingenious and diabolical, his type spread like mold wherever settlers moved, and brought with it an endless supply of sellable goods and weightless, friendly babble. Fundamental to his appeal, Rourke explains, was the fact that he was made of 100-percent baloney:

Masquerade was as common to him as mullein in his stony pastures. He appeared a dozen things that he was not … Listless and simple, he might be drawn into a conversation with a stranger, and would tell a ridiculous story without apparent knowledge of its point.

The British in particular seized upon this American character, inserting him into a series of 19th-century "Yankee plays" that were reliably popular on both sides of the Atlantic. "In each the Yankee was a looming figure," Rourke writes.

He might be a peddler, a sailor, a Vermont wool-dealer, or merely a Green Mountain boy who traded and drawled and upset calculations … But he was always the symbolic American. Unless he appeared as a tar his costume hardly varied: he wore a white bell-crowned hat, a coat with long tails that was usually blue, eccentric red and white trousers, and long boot-straps … Half bravado, half cockalorum, this Yankee reveal the traits considered deplorable by the British traveler; he was indefatigably rural, sharp, uncouth, witty. Here were the manners of the Americans! Peddling, swapping, practical joking, might have been national preoccupations.

What we have here is the archetypal huckster, a linguistically advanced simple man with pretensions to the upper class. Dressed in the veneer of respectability, he was always ready to peddle, to trade, to do business. Even if this character was mostly mythological, an invention of British tourists, it still entered the American consciousness fully enough to affect our conception of ourselves. So by the time sales and trading became the province of the well-to-do, he was something we looked out for and recognized in our midst. Sinclair Lewis's Babbitt, one of the best-selling American novels of the 1920s, is essentially a 400-page parody of this kind of goon. When the title character hosts his rotary club buddies and their wives for dinner, for example, he plies them with cocktails and the conversation gets self-lovingly salesmanish:

When, beyond hope, the pitcher was empty, they stood and talked about prohibition. The men leaned back on their heels, put their hands in their trousers-pockets, and proclaimed their views with the booming profundity of a prosperous male repeating a thoroughly hackneyed statement about a matter of which he knows nothing whatever.

Lewis wasn't the only famous satirist who perceived madness roiling just underneath the middle-class veneer. In his writing and particularly in his comics, James Thurber spent the 1920s, '30s and '40s filling the New Yorker with images of ostensibly normal, New Yorker-reading people just barely in control of their violent tendencies, sexual anxieties, and marital misery. When suburban sprawl became inexorable after World War II, literary writers tended to depict the quiet, picket-fence neighborhood as a tragic scene. The gentler, more surreal approach was left to comedians, particularly the boundary-pushing standup of Lenny Bruce, Shelly Berman, and Jonathan Winters, who saw any kind of perceived normalcy or authority as potentially, if not expressly, deranged.

Performances like this are what initiated the counterculture of the '50s and '60s, as R. Crumb—like Hartman, the son of a salesman who came to prominence because of rock-album art—made abundantly clear. For Crumb, any kind of gray-flannel-suit-dom was a pathetic attempt to suppress one's most terrifying instincts.

In the brilliant 1994 documentary about his life, Crumb speaks at length about "Japanese smiling disease," better known as "smile mask syndrome," wherein a person (typically one in a sales job) is require to grin so often that they develop depression. Steve Martin, the most popular stand-up comedian in the country at the time when Hartman was illustrating Poco's Legend and Steely Dan's Aja, essentially turned this idea into his bread and butter. With his white suit, strong chin, and cropped hair, Martin could come out and give a slow-burn monologue about believing in family while standing in front of a giant American flag. "And people say I'm crazy for saying this," he transitioned seamlessly, "but I believe that robots are stealing my luggage."

So when Hartman appeared on television in the mid-'80s, depicting the president as a deceptive mastermind, lawyers as cold-hearted sociopaths, and corporations as pathetically desperate, he was simply fulfilling the promise of generations of American comedy. It wasn't just would-be Babbitts or visibly repressed normals who were full of it; everyone was. Advertising and Hollywood had made us all image-crafters, performers, and sales experts.

In his final film role, a small but significant part in Joe Dante's 1998 masterpiece Small Soldiers—the director's third woefully underrated satire of the '90s, following Matinee and The Second Civil War—Hartman was cast as the dimwitted suburban father whose kids inadvertently invite the wrath of battle-ready action figures specially programmed with munitions expertise. It's a genuinely cutting film about the ways in which the military and entertainment industries have become intertwined, and Hartman's character, a genial, combat-movie-obsessed boob who thinks he's the right man for warding off this dangerous army, is given the most biting line. Watching an explosion-filled film on TV, he pauses between blithe handfuls of popcorn to tell his bored wife, "I think World War II is my favorite war."

You Might Remember Me contains some fascinating details about Hartman's scuttled plans for his post-SNL career, including a variety show and even a few revolving vehicles for Chick Hazard. Needless to say, none made it to air, though Hartman eventually enjoyed a successful second act as NewsRadio's Bill "The Real Deal" McNeal, another thick-headed smooth-talker with rage issues.

Hartman was once again the successful, supportive uncle in a cast of newcomers, and by all accounts he enjoyed the work. But here, as at SNL (and the Groundlings, where he helped create Pee-Wee's Playhouse with Paul Reubens before the latter took the show to kids' TV), Hartman couldn't manage breakout popularity. Something about his very consistency—Thomas has no shortage of quotes from coworkers about Hartman's ability to improve every scene—prevented him from achieving the surreal performative heights of someone like Eddie Murphy or Chris Farley. Or, for that matter, Jonathan Winters, Steve Martin, and R. Crumb.

Instead, Hartman lent his voice and his mannequin smile to The Simpsons, NewsRadio, and a few underwhelming movies, and always found time for surfing on his beloved Catalina Island. He left behind no great starring role or iconic sketch. In fact, one of the great joys of looking back at his career is the preponderance of one-off brilliance, like "Robot Repair" or the uniquely moving 1987 SNL short film "Love Is a Dream," which Thomas touts as a rare look at Hartman outside laugh-a-minute mode.

It's a nostalgia piece about an old woman's memories of a soldier she loved, and Hartman was clearly attuned to the studio-romance aspect. It was just one more '40s-style role for him to inhabit, and it's a beautiful few minutes of TV filmmaking, but Hartman never got the chance to write for himself, so otherwise he was stuck playing buffoonish authority figures, however brilliantly conceived.

And then, of course, came his tragic and brutal murder, which Thomas discusses tactfully but agonizingly. Shot in his sleep by his jealous, drug-addicted, and unhappy wife, Brynn, Hartman's murder left a gaping hole in the comedy world. Who else could play so many kinds of people? Who else was so beloved? Stephen Colbert, Steve Carrell, and of course Will Ferrell have since made their careers on blowhard characters, but Hartman was simultaneously more broad-ranged and more limited than any of them. It was rare to see him totally silly, but he showed that smooth voices and looser morals existed everywhere, from the President on down to lowly b-movie stars and suburban dads. When you heard his voice rev up, a parody of authority no matter what he said, there was always one message: You might remember me from … everywhere.

John Lingan has written for Slate, The New Republic, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and lots of other places. He lives in Maryland, and is on Twitter.

Image by Tara Jacoby.

The Concourse is Deadspin's home for culture/food/whatever coverage. Follow us on Twitter: @DSconcourse.