Today Sports Illustrated published a story about how Manny Pacquiao, boxer and sitting Phillippine senator who said gay people are worse than animals and that drug dealers should be killed, is a wise man who just loves boxing. It was very well received by Manny Pacquiao.

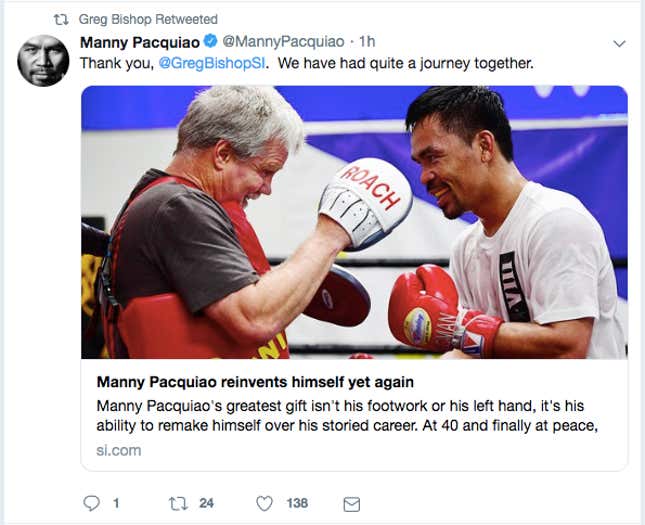

Written by Greg Bishop and titled “Manny Pacquiao Reinvents Himself Yet Again,” the profile—loosely hooked to the not-at-all contrived exercise of looking at some old photos of Pacquiao—takes stock of the boxer’s life and career, or at least the parts that can be used to portray Pacquiao as a sympathetic figure ahead of his upcoming fight this weekend.

The piece follows the well-established pattern favored by a certain breed of sportswriter who can’t imagine balancing access to a famous athlete with any sort of criticism of the famous athlete: Present-tense opening scene of the famous subject being famous (“Breakfast has just ended at his mansion in Los Angeles, where members of his entourage dispense gobs of hand sanitizer”); unsubtle transition to a time in the past when the person was not famous (“His eyes linger on a laptop. His mind drifts back in time”); and a vague discussion about how the person has changed (“So many Pacquiao iterations, so many career turns, so many revenue streams created”). Then follows the briefest of references to bad things the person did that manages to distance the writer from them, reframe them as an obstacles for the subject to overcome, and avoid actually asking the subject about them, all in one efficient paragraph:

How did he come back from the losses, the knockout, the brink of divorce? How did he repair the damage done by the inexcusable comments he made on same-sex marriage that drew the ire of gay rights groups and cost him sponsors, including Nike? He kept fighting. For the money, of course, but also for his family, his career and his damaged reputation.

Finally, the writer presents the subject as a sobered, changed man, who is “at peace.” The story ends with a scene at Pacquiao’s mansion, where he’s being waited on by his entourage:

He’s asked if he might fight until age 50, like Bernard Hopkins did. He’s not sure, he says. But he can see his future, his next reinvention. He wants to become the first person to be president of his country and world champion at the same time. And, yes, that sounds both crazy and not implausible, given everything else that happened to Manny Pacquiao, in large part because of Manny Pacquiao. The best and the bad.

It’s strange, in that moment, to think back to Frosted Tips Pacquiao and Up All Night Pacquiao. Crazy to imagine how high he rose and how far he fell and square all that with the man hosting this breakfast, who seems both wiser and content and like he knows he’s near The End and wants to stay in the moment, to remember what he went through and why it matters and how it led to right here. The pictures tell that story, tell why he is still fighting, better than the boxer can.

What is this supposed to mean, exactly? What’s “strange” or “crazy” about squaring Pacquiao’s long and successful career with the image of him living in luxury and having breakfast served to him by his entourage?

This is the kind of empty pontificating that’s produced when a writer is straining to avoid confronting any of the less savory, and thus inherently more worthy of examination, parts of the subject’s character. Instead of stopping to consider what it would mean for the people of the Philippines if Manny Pacquiao, a bigoted politician who advocates for state-sanctioned murder, actually achieved his stated goal of becoming president of his country, Bishop zooms right ahead to the writerly ending he wants: nostalgia for Pacquiao’s ongoing boxing career. “Sticking to sports” is basically never a feasible goal, but it’s an especially insufficient approach when the subject of the profile has a contemporary career as a powerful politician and ambitions to become president.

When the subject of a profile praises the profile, it usually means the reporter should have dug a bit deeper or been a bit more critical. When the profile in question is about Manny Pacquaio, included only quotes from Pacquaio and people in his camp, made only a glancing reference to Pacquaio’s bigotry while ignoring other alarming parts of his political beliefs, and Pacquiao not only praised the profile, but expressed gratitude for it, the reporter has essentially performed the job of a flack. And when that reporter then retweets the subject’s gratitude, it’s safe to say the plot’s been lost entirely.