Originally published on Sportsgeekonomics.

When the "Summary of Postseason Football Institutional Bowl Expenses" comes out each April, someone digs into a major bowl's numbers and pronounces that one or both of the teams that participated in the bowl game lost money. Generally speaking, nothing could be further from the truth, and this false impression likely stems from the fact that these articles are written by experts at sports, rather than experts at finance. (The same problem might emerge if I were accepted as an expert on the relative merits of a 4-3 vs. a 3-4 defense). But because this sort of reporting is widely accepted to be true, the public dialogue over the football post-season has certain misperceptions baked into the debate, and there is potential for bad policy decisions to emerge because of bad economic analysis about the profitability of the BCS bowl system.

For example, in 2011 Craig Harris of the Arizona Republic and USA Today wrote the following (and not to pick on Craig Harris—this is a common story that seems to run annually): "Virginia Tech lost big on the field—and financially—in the 2011 Orange Bowl."1 But while Harris's depiction of Stanford's on-field "drubbing" of Virginia Tech was accurate,2 with respect to the supposed financial bath that the Hokies took, his analysis misses the mark.

Virginia Tech is a member of the ACC. The schools that constitute the ACC have made a series of decisions to share revenues and expenses of teams as relates to postseason football participation. As one example, the ACC members have agreed to pay a good deal of each bowl participant's expenses to attend the bowl they are invited to (though not all of those expenses). As another example, the ACC members have agreed to share equally any revenues that its members receive from bowls, after accounting for some portion of the participant's expenses. So basically, this is straight out of Karl Marx: Revenue comes in "from each according to his abilities" and expenses are paid out, more or less, "to each according to his needs."

When Virginia Tech goes to the Orange Bowl, there are really two economic transactions. The first is the basic, capitalist one—Virginia Tech goes to the Orange Bowl, receives a payment, incurs some expenses, and then receives some ancillary pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits. The second transaction is the "socialist" one—Virginia Tech surrenders much, but not all, of the revenue it receives and in exchange gets much, but not all, of its expenses covered.

(As was pointed out to me by Twitter commenter @uvaeer, the money may never actually reach Virginia Tech, as it may be sent directly to the ACC, but that accounting detail doesn't change the underlying fact that the Orange Bowl paid for Virginia Tech to play in the game, whether Tech keeps the money or not. If the state garnishes the wages of a deadbeat dad for child support, we don't say his employer didn't pay him.)

The problem with the economic analyses one typically sees is that they confuse the question of whether the Orange Bowl is profitable for Virginia Tech with the question of whether ACC membership is profitable for Virginia Tech (and more specifically, whether the revenue- and expense-sharing rules of the ACC with respect to BCS bowls are profitable for Virginia Tech). Those are very different questions. This is why it is important to understand the economics, because if you don't, you end up getting the analysis backwards. Answering the second question (is the ACC screwing Virginia Tech?) but thinking you are answering the first question (is the Orange Bowl screwing Virginia Tech?) results in people thinking that going to bowls, even major ones like the Orange Bowl, is bad business, when in fact, as I show below, it is a massively profitable enterprise, even before all of the very lucrative intangible benefits are considered.

And in case you think I am focusing on ancient history, talking about the 2011 Orange Bowl with the 2014 edition looming, the same is true for the 2012 Orange Bowl, where Clemson lost 70-33 to West Virginia, and where news reports focused on how they supposedly lost money on the trip.

And just last week, the following piece appeared in USA Today, describing, among other things, how dissatisfied Florida State was with the fact that it lost money on the required purchase of tickets for the 2013 Orange Bowl.

"What would be ideal for conferences would be to have no ticket commitment, and what would be ideal for the bowl would be to have the whole stadium committed to the schools and conferences," said Carparelli, who is also senior associate commissioner of the American Athletic Conference. "Somewhere in between, the economics have to work for both parties."

It didn't work for Florida State last season. The school reported to the NCAA in a document obtained by USA TODAY Sports that it was "very dissatisfied" about having to buy 17,500 full-price tickets to play in the Orange Bowl, where the Seminoles defeated Northern Illinois. FSU sold a small portion of that allotment and needed help from the Atlantic Coast Conference to pay $2.1 million for unsold tickets. The loss caused FSU to exceed its expense allowance by $1.4 million, and the school cited the easy availability of cheaper tickets as a reason.

"The price of the tickets were too high and the secondary market had tickets at a much lower cost, which made it impossible for us to sell our allotment," Florida State reported on an official survey form afterward.

(I should note that the author of this article, Brent Schrotenboer, does add in a caveat that if you take the money the ACC teams get from other bowls, Florida State came out ahead. But that misses the point, which is that you can't look at one element of a multifaceted transaction and make a rational economic judgment about the entirety based on that one line item in isolation. Nor should you confuse cross-subsidies with the underlying profit of an activity. The Orange Bowl profit is not coming from the ACC's participation in other bowls; the Orange Bowl itself is profitable and a proper analysis would show that, even without need to look to revenue from the Belk Bowl, etc.)

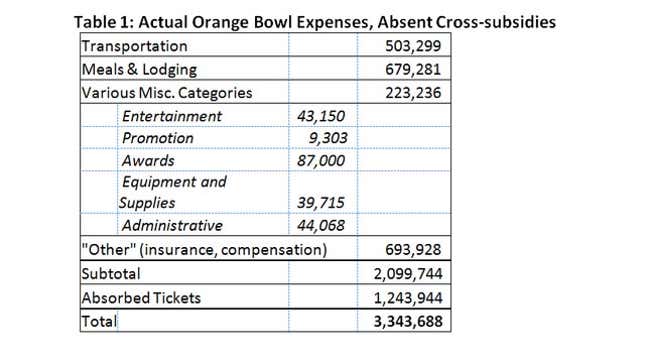

Anyway, let's start with the simple question of whether going to the Orange Bowl would be profitable if Virginia Tech or Clemson or Florida State were not involved in a "makers-vs-takers" agreement with its fellow ACC members. This is a very simple calculation. First we need to look at the revenue the Orange Bowl paid out: $22.5 million. Next, we need to look at the total unsubsidized cost to Virginia Tech of attending the game, including travel, accommodations, the purchase of unsold tickets, etc. This latter category, unsold tickets, often gets people into a frenzy about how bowls exploit schools, and I will discuss that later in this analysis, but for now, let's just accept the fact that the Orange Bowl did make Virginia Tech pay for tickets that went unsold and include that in the total expenses of attendance.

According to the 2010-11 Virginia Tech bowl report, the team had $1.725 million in expenses that the ACC covered. Virginia Tech treats this as revenue (because effectively the ACC sends them a check) but for us to look at the pure Orange Bowl/Virginia Tech transaction, we're going to ignore that money because it has nothing to do with the Orange Bowl deal and everything to do with Virginia Tech's deal with the ACC. Actual expenses include just a shade over $500,000 for transportation, a little under $700,000 for meals and lodging, and another approximately $225,000 to cover Entertainment ($43,000), Promotion (9,000), Awards ($87,000), Equipment and Supplies ($40,000), and Administrative costs ($44,000). Combined, those costs total something very close to $1.425 million. Then Virginia Tech also list another approximately $700,000 in "other" expenses, which the school describes as consisting of "insurance, supplemental compensation, wages, and FICA," so this sounds like where all the bonuses paid out to coach Frank Beamer and his staff are hidden. So that brings the total expenses up to $2.1 million. And then finally, Virginia Tech states that it had just under $1.25 million in unsold tickets that it (and the ACC) had to pay for. While the out-of-pocket cost to Virginia Tech for this item was only $46,301, that's only because of the ACC subsidy (which we want to keep out), so including the full cost of those tickets brings the total Orange Bowl expenses up to a bit over $3.3 million.3

Now for my promised tangent on the issue of mandatory ticket expenses. You will hear people decry the fact that the Orange Bowl requires Virginia Tech to stay at specific hotels at specific prices (which in 2011 resulted in a $700,000 expense), rather than negotiate a better deal to stay where it wants at a lower price. You will also hear how bad a deal it is that Virginia Tech (or the ACC) has to pay for the unsold tickets (which in 2011 resulted in a $1.25 million expense4). It is true that the Orange Bowl did impose these costs on Virginia Tech but at the same time it paid them $22.5 million. Would there be an equal amount of outrage if the Orange Bowl payout was $20.5 million, rather than $22.5 million, but the Orange Bowl provided free accommodation at the hotel of its choice and agreed to take back up to $1.25 million in unsold tickets for free? Because in terms of the bottom line (leaving aside who bears the risk, which I discuss below as my final point), those two transactions are the same. If it's hard to imagine anyone getting really worked up about the latter deal—$20.5 million, free accommodation for the entire Virginia Tech entourage, and no ticket purchase requirement—then maybe we should calm down our outrage over the former, which works out to be basically the same thing.

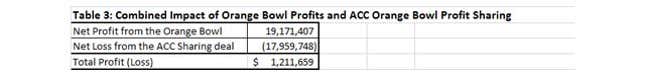

Anyway, even with those supposedly burdensome expenses imposed by the Orange Bowl, the deal is extremely profitable. Revenue from the Orange Bowl of $22.5 million. Total expenses of $3.3 million. Thus, Virginia Tech's profit from going to the Orange Bowl was $19.2 million. This is a far cry from any supposed financial loss the Hokies incurred. They made money hand over fist, and any analysis that ignores or confuses that fact is selling you a bill of goods.

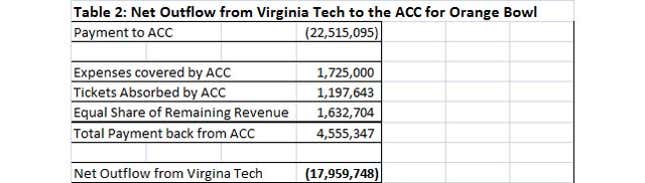

But, as we know, neither Virginia Tech nor Clemson is operating in an Ayn Rand individualist society. Both schools, as well as Florida State, belong to a scandalously collectivist organization known as the ACC. (I hope it's clear I am being a little facetious with the Rand references.) The ACC offers some pretty good benefits, including lucrative television contracts. And membership in the ACC actually helped Virginia Tech snag its coveted spot in the Orange Bowl to begin with. But while membership has its privileges, it also has its costs. So now we need to look at the other half of Virginia Tech's Orange Bowl deals—the one it made with the ACC.

This deal involved payments by the school to the conference and by the conference to the school. The former involved Virginia Tech giving the ACC all of its $22.5 million haul from the Orange Bowl. In return, the ACC gave Virginia Tech a $1.725 million expense allowance; the ACC absorbed just under $1.2 million in unsold tickets; and the ACC gave Virginia Tech an equal share (i.e., 1/12th which will become 1/14th for future sharing) of the remaining money, which works out to be about $1.6 million. This amounts to a net payment back to Virginia Tech of $4.6 million.

On its face, this is a horrible deal for Virginia Tech, yielding a net loss of just under $18 million. And indeed, that loss—$17.96 million—is large enough to almost wipe out Virginia Tech's Orange Bowl profits; the net of the two deals is only about a $1.2 million profit to Virginia Tech.

(Forgive me for a small aside but when I first did this calculation, it was giving me fits as to why the Hokies said they lost around $420,000 but that even when I reversed all of the transactions, I still showed a profit of $1.2 million. I put in a footnote asking for readers to help solve the puzzled and with help from one, I was able to figure out that Virginia Tech was actually including ZERO dollars of Orange Bowl revenue, rather than 1/12th as I had assumed they would. If you back out the $1,632,704 that represents Virginia Tech's 1/12th share of the Orange Bowl money, you comes within a dollar of a perfect match, so puzzle solved!5

(However, the solution to that puzzle is actually really revealing. It means that for the Hokies to show a loss on its trip to the Orange Bowl, they had to make an accounting assumption that their revenue from the Orange Bowl was zero. Literally, it zeroed out every penny the Orange Bowl paid it (and to the ACC) and then showed a financial loss! Should we really be surprised that once $22.5 million are left out of the analysis, the accounting comparing the ACC's partial defrayal of Virginia Tech's expenses shows that Tech spent a little money? Would ANY business look profitable if first you zeroed out the revenue? I'm almost speechless at this discovery. But anyway, back to the analysis …)

To emphasize this point again, the fact that Virginia Tech negotiated a very lopsided deal with the ACC, in which it transferred a gross $22.5 million (and a net $18.0 million) to its fellow conference members even though those teams did not go to the conference's most prestigious bowl game, says nothing about the profitability of the Orange Bowl and everything about the nature of the ACC and its efforts to "share the wealth."

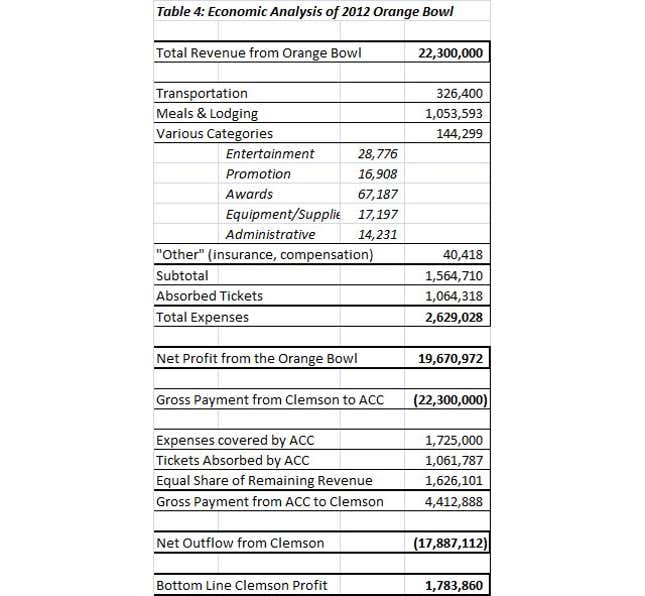

I've done the same analysis on the 2012 Orange Bowl trip that Clemson took. Rather than losing $185,000, as the newspapers reported, Clemson netted $19.7 million from the 2012 Orange Bowl. The math is simple. Orange Bowl revenue was $22.3 million. Total expenses were $2.6 million. Hence, a profit of $19.7 million.

Then, in a second transaction, Clemson surrendered all of its Orange Bowl revenue to the ACC; in exchange the ACC covered some of Clemson's expenses and gave Clemson a twelfth of the remaining profits. The result was a net payment by Clemson to the ACC of $17.9 million, leaving it with $1.8 million.

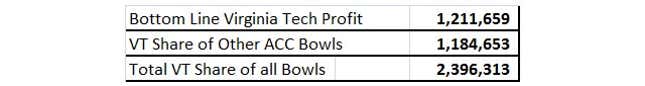

Moreover, don't forget that the money that flows into the ACC from Virginia Tech doesn't just disappear. Virginia Tech shares that money with its conference partners, just as they share their bowl revenues with Virginia Tech. So in addition to having a good portion of its expenses covered in return for surrendering a substantial portion of its Orange Bowl revenue, and in addition to the 1/12th share of the Orange Bowl money the Hokies got to keep, Virginia Tech also got another $1.2 million (just a coincidence, it doesn't equal out each year) back from the ACC from revenue from other schools' bowl payouts.

Table5A: Virginia Tech net profit, including other ACC bowls

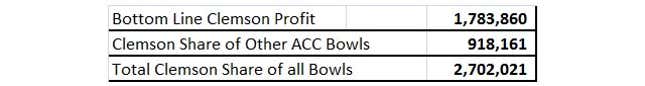

The same was true in 2012 for Clemson. Clemson's Orange Bowl profits went to the other ACC schools—around $1.6 million per school. In return, Clemson got a share of the other schools' bowl revenues, totaling around $900,000. In all, Clemson netted just over $2.7 million.

Table5B: Clemson net profit, including other ACC bowls

Brent Schroetenboer understood this aspect of things in his USA Today piece, but I think he overemphasized it as the reason the ACC is profitable with respect to bowl games. The Orange Bowl isn't profitable because it is subsidized by the Chick-fil-A Bowl. It is profitable, period. And then, the ACC takes away those profits and doles them out in a fashion that rewards Wake Forest for its 4-8 season, in almost equal measure as its champions.

Rather than just throw up our hands in puzzlement at why one of the most American of sports has an underlying set of financial subsidies from the strong to the weak that would make Fidel Castro proud, let's think about why Virginia Tech and Clemson would voluntarily enter into such a seemingly one-sided and incentive-sapping agreement .

First there is the obvious, which has already been mentioned: In exchange for giving up almost all of its Orange Bowl profits, Virginia Tech gets to share in the lucrative ACC television contracts. As an independent, Virginia Tech would be unlikely to command Notre Dame-like television revenues. And similarly, ACC membership is what earned Virginia Tech its Orange Bowl bid in the first place. So as I mentioned before, membership clearly has its privileges.

But there is more to it than that. One way to think about this is to ask why the ACC doesn't agree to cover all of Virginia Tech's expenses. Instead, the conference has rules that cap the expenses it will cover for the school. The school incurred a total of $3.4 million in expenses, but the ACC covered only about $2.9 million of that, based on a flat $1.725 in expenses, plus an agreement to absorb about $1.2 million in unsold tickets. The decision to cap the reimbursed expenses is a choice all of the schools in that conference make. The sharing of the bowl proceeds could occur after all expenses are covered, which would effectively ensure teams don't lose money from major bowls, but there are good reasons not to do that.

Economically, if Virginia Tech spends money to send a donor down to Miami, they are going to reap 100 percent of the after-effect benefits of that trip. The donor is going to potentially give more to Virginia Tech, rather than, say, to Virginia. So if Virginia is subsidizing Virginia Tech's expenses, Virginia Tech has a strong incentive to spend more money when that spending of shared money generates private gains for Virginia Tech. As an extreme example, imagine if Virginia Tech just gave its boosters $1,000 in spending money when they got to Miami and called that an expense, and then told the donors to contribute the money back in February. While that is a pretty crass example of gaming the system, flying the donors down in a private jet instead of on a commercial flight has the same effect (it's just a little less obvious if they donate $1,000 for a $1,000 flight rather than for $1,000 in spending money), and so a conference needs to be careful when it decides how much of the school's expenses to cover. Without such a cap, it is unambiguously in Virginia Tech's interest to drive up its expenses to a much higher level, especially if those shared expenses will result in unshared outside revenues. The net result would be that the ACC Orange Bowl-related expenses would go through the roof. And so would the expenses from all of the other bowl games. And so everyone in the ACC, including Virginia Tech, would end up spending more to go to bowl games than it does now.

You've probably actually experienced this phenomenon in your own life, when you go out for dinner with friends and you know you're going to end up splitting the check equally. Someone orders a drink. All your other friends know they're paying for that drink, but only the guy drinking it will get the pleasure. So someone else figures he'd like to have his drinks subsidized by his friends too, and pretty soon everyone has ordered a drink, or two, and you end up with a much higher bill for drinks with your dinner than if you'd all been paying individually. Basically, the ACC caps the expenses it shares so that it can make sure its member schools don't run up the tab on the collective dime. And since Virginia Tech has to pay for everyone else's "drinks" when they go to bowl games, Virginia Tech benefits from agreeing to cap its own reimbursement because it means it has to reimburse everyone else less, both for the less prestigious bowls in 2011, but also in future years when other teams, like Clemson, make it to the Orange Bowl. So it's not so much that Virginia Tech wants a system where it can run the risk of losing money (through under-reimbursement of their expenses), but rather it's a system the ACC sets up (which Virginia Tech supports) to help hold down total conference expenses.

Nevertheless, Virginia Tech chose to spend more than its subsidy, so we know that the reimbursement level chosen was actually below the optimal amount—Virginia Tech still felt it had expenses it could lay out that were worth incurring. And so what's clear is that despite the seemingly socialist element of subsidizing Virginia Tech's expenses, the ACC actually picked a number below Virginia Tech's actual need (and thus also well below the inflated level you might get from the shared-drinks problem). The direct result of this is to lower Virginia Tech's profits by driving up Virginia Tech's portion of the expenses while still only giving the Hokies an equal share of the revenue. Why would the ACC choose to under-subsidize Virginia Tech expenses?

First, schools probably have an excessive desire to spend on winning, with respect to the collective ACC finances. Only one ACC team is going to get the ACC's guaranteed BCS bid, so except in those years where the ACC gets two bids (like this year, with Florida State going to the national championship and Clemson going to the Orange Bowl), the drop off from first to second place is fairly hefty.6 In a winner-take-all market, the total spending by all of the contestants may exceed the value of the pot. I may overspend a little if I think the extra $10,000 will push me over the edge, but you think that, too, etc. Since the ACC pretty much is guaranteed that $22.5 million regardless of who wins, those extra $10,000 here and there aren't growing the size of the collective profit pie, they are just frittering it away.7

But if the ACC can make winning a less attractive thing, financially, then each school is a little less inclined to overspend. One way to do that is to make it clear to the school that although there are all sorts of benefits from winning, a huge financial windfall from the Orange Bowl itself is not one of them. If the prize is a $19.2 million payday, an extra $1 or even $2 million here or there might seem reasonable to try to lock that in. But if schools know that the $19.2 million in profit from the Orange Bowl is going to be shrunk down to $1.2 million, incurring another $1 or $2 million starts to look less reasonable. In other words the ACC schools in aggregate want to make winning less attractive, financially, so that then each school is a little less inclined to overspend. So when the Hokies agree in advance to give up their millions to the ACC, they do it because they know this is good for them in the long run. Think of it as the Frank Beemer version of Odysseus lashing himself to the mast to avoid the Sirens' call of "overspending" on football.

But despite those disincentives, Virginia Tech still overspent. Why? Because no matter how much the ACC tries to make it undesirable to win, all of the off-the-books benefits make it good to win. Winning the ACC and going to the Orange Bowl has many spillover benefits beyond the narrow revenues and expenses of attending the Orange Bowl itself. Among these benefits are improved athlete recruiting (and thus more wins in the future), higher donations (and thus more profits), an improved non-athlete applicant pool (which can result in more students or better students, and most importantly, a higher price charged to those students, and thus more profits in a way that will never show up on the athletic department's P&L). All of these spillover benefits accrue privately only to Virginia Tech. With all of those extra private incentives out there, plus the general positive feeling that comes from winning, plus a small profit, it is no wonder Virginia Tech wants to spend more than the ACC thinks is worth subsidizing.

(Another aside: This is why schools generally still want to go to even the smaller bowls with smaller cash payouts. The off-the-books revenue benefits are high, so high that as the BCS evolved into the CFP and it looked as if smaller conferences might be shut out of the major bowls, those schools have worked to create more, not fewer, bowl games for the lower half of FBS football.)

With respect to any bowl, conferences have the standard problem of any organization that shares expenses but can't share all of the benefits. As a result, the ACC and its member schools are engaged in a very complex economic engineering effort. The balance is tricky. Long-run revenue is maximized when ACC schools excel versus other conferences, so presumably, all ACC teams want some spending so that its best teams can compete with the best of other conferences, or in the long-run its TV deal will shrink, etc. But in the short-run, there is little or no direct additional pecuniary benefit to the conference as a whole to any given team winning versus any other.8 And since every school gets tremendous non-pecuniary benefits from winning, it certainly looks like the ACC "overshares" the Orange Bowl revenue (i.e., it takes more of it than seems warranted, which is why people think Virginia Tech loses money) but the conference does this because it wants to dampen the competitive pressure that results in (so-called) overspending. But the ACC still allows Virginia Tech the chance to break even or even earn a small profit (on top of which Virginia Tech also garners all of the ancillary benefits) because the ACC doesn't want to outright kill Virginia Tech's (and the other ACC schools' ) incentive to win. The conference just wants to tame it a little.

The goal is a mildly profitable Orange Bowl, and the revenue and expense sharing needed to get there can make things appear as if the teams going to the most lucrative bowl are losing the most money. But they aren't. Not by a long shot. When the school that goes to the Orange Bowl chooses to spend a bit more than its extremely reduced share of the total direct profits (again, leaving aside all of the off-the-book benefits) so that the school appears to have an accounting loss, such as the reported $420,000 that the Hokies supposedly lost in 2011, don't blame the BCS or the bowl system in general; blame the express decision of the ACC (which of course is just the collective decision of the ACC schools themselves) to structure the system to minimize profits and reduce the incentive to spend on (a) travel and (b) winning. It is the after-the-fact impact of that economic engineering, corporate socialism if you prefer, that makes the Orange Bowl look like a money loser, not the Orange Bowl itself.

Finally, I promised to discuss the shifting of risk between bowls and schools inherent in the mandatory ticket guarantees and the requirement that schools use bowl-approved hotels at bowl-negotiated rates. All else equal, the Orange Bowl would rather not bear the risk of selling tickets if it can get Virginia Tech to pay for them in advance, leaving Virginia Tech to run the risk of not selling them all. Even better if the Orange Bowl can jack the face value up to a price above the likely market value and make Virginia Tech pay the Orange Bowl more than the likely revenue from selling those tickets. That may be the current situation, except that all else is NOT equal. In order to get Virginia Tech and the ACC to buy unsold tickets, whether those tickets are overpriced or not, the Orange Bowl has to pay Virginia Tech more money to come to the bowl than it would if it did not impose a mandatory ticket purchase. In a perfectly transparent, competitive market (which of course is pretty rare!), for every additional expected dollar of ticket cost you want the Hokies to eat, you have to pay them an extra dollar in revenue.

Of course, with that said, Virginia Tech would be better off if it could get all of the money it now gets but not have to run the risk of not selling the tickets. Virginia Tech would like to have the Orange Bowl assume those tickets will sell and pay Virginia Tech accordingly, but then have the Orange Bowl go out and make it happen, and have the Orange Bowl suffer any short-fall, rather than Virginia Tech. As college football moves into the playoff era, the conferences have realized they have enough leverage to shift this risk, effectively telling the bowls that if they want to stay relevant to the playoff situation, the bowls will have to bear the risk of unsold tickets, rather than the schools. As fans, I think this is good for us—the tickets may be priced more rationally because the entity pricing them (the bowls) will now also have to sell them at those prices.9 That entity (e.g., the Orange Bowl) will price into its decision to use, say, Groupon, to sell its leftovers with the impact it will have on the sale of the tickets to alumni, whereas currently, they may not care how much they depress the primary market by creating an active and inexpensive secondary market. But this shifting of risk, while important, is a second-order consideration. The bigger picture is that the current system effectively compensates Virginia Tech for bearing that risk by paying the school more to attend the Orange Bowl than it would otherwise merit if it weren't agreeing to bear that risk.

So another aspect of this story is that by moving to a playoff format, and putting the bowls at risk of being relegated to a distant second place, the schools are in the driver's seat in these re-negotiations. Not surprisingly, the risk is shifting to the bowls and profit is shifting to schools and away from bowls and their allies. What's astounding is that the schools resisted this so long.10 But as we move into the bold new era of a college football playoff, it's important to remember that as poor a product as the BCS system may be for truly determining an undisputed national champion,11 it has not been a money loser for the schools invited to the BCS Bowls, despite what many opponents of the system want you to believe.

Update: So, just as soon as I've published something with a broad audience, I've discovered one of the perils of having people actually read my work. I made a mistake. Not a huge one, but one I want to correct and explain. I got a very nice email from Brent Schrotenboer, the reporter who wrote the USA Today article on Florida State's complaints about having to pay full-price for tickets that had to compete with other tickets sold at a discount through Groupon.

I was focused on the article's explanation that having to pay for Orange Bowl tickets caused Florida State a "exceed its expense allowance by $1.4 million" because:

FSU sold a small portion of that allotment and needed help from the Atlantic Coast Conference to pay $2.1 million for unsold tickets. The loss caused FSU to exceed its expense allowance by $1.4 million

I noted that Schrotenboer added "in a caveat that if you take the money the ACC teams get from other bowls, Florida State came out ahead."

I narrowly focused on this sentence: "The bowls are profitable overall for the major football conferences when the revenue and expenses for all games are combined." But Brent very politely pointed out to me that's not what he was saying, as I would have seen if I'd focused on "Last year, the conferences collected a record $210 million profit from the bowls. But that profit was largely driven by the five games that constitute the Bowl Championship Series: $202 million from the Rose, Sugar, Orange and Fiesta Bowls plus the national championship game."

So that's my bad, and I apologize to Brent.

But fascinatingly, in Brent's email, he also told me that UConn insists it lost money on the Fiesta Bowl, which he attributed to a narrow focus on a single-year's worth of revenue-sharing agreements and accounting. So, without saying that Brent Schrotenboer believes this (I don't think he does), this actually gets right at the heart of my point, which is that bad accounting can fool some people (including UConn itself) into thinking the Fiesta Bowl is a money-loser, when in reality it's the nature of your conference agreement that causes the paper losses. If accounting has any purpose at all, it should be to inform businesses to make smart financial decisions, but UConn appears to have been fooled by its own accounting.

And so it is my small hope that by pointing out the difference between solid economic analysis and and expense report, I can help people sort out the difference between a school exceeding its conference reimbursement amount and actually losing money.

2 Among the highlights of this game were Shayne Skov's "12 tackles, including three sacks and five tackles for loss."

3 This is an approximate number that is the result of a lot of rounding. The actual down-to-the-dollar total is $3,343,688.

4 It's also not clear that the accounting entry actually captures the true cost of eating those tickets. Looking at Virginia Tech's 2011 Orange Bowl expenses shows that the school and the ACC ended up paying for unsold tickets with a total face value of $1,243,944 and treating that as a 100 percent loss. That overstates the true cost to the school and conference unless they are literally shredding those tickets. Who gets them? Virginia Tech or other ACC school employees? Then that's a perk to those employees that may allow for slightly lower pay scales at ACC schools. Donors? Clearly that's a perk that will grow future donations. In any case, a very big question is what happens to those tickets. It may not change the accounting, but to the extent the schools (both Virginia Tech and its conference-mates) benefit from those "absorbed" tickets, valuing them at zero is wrong.

5 Thanks to commenter John for pointing out this elegant solution to my puzzle.

6 And even if a second ACC does get invited, the current BCS rules result in the second team earning closer to $5 million in revenue rather than $22.5 million.

7 As a note, though that "just frittering it away" is in some sense the essence of economic competition, and the desire to avoid "just frittering it away" often the root impulse of anticompetitive price fixing. Throughout this analysis, I am assuming the ACC as a joint venture of a small number of colleges is not running afoul of the antitrust laws. To the extent it is acting anticompetitively, that doesn't change the reasons for the system, just its legality

8 Although, again, because the BCS provides a large payout if a conference produces a second BCS team, there is some benefit for having two good teams, but the incentive is much less and there is even less incentive for a conference to generate a third great team.

9 And similarly, if the hotel burden shifts, so that the school shops around and gets a better deal on hotels, rather than having to use the hotel that paid the bowl a sponsorship fee (i.e. a kickback) and in turn is allowed to charge a higher-than-market rate to the school, the total cost of hosting the bowl game will decline and so there are likely net benefits from untangling the cross-subsidies and the risk burden.

10 One possible explanation is that until very recently, conference commissioners did not share very much in the profits they helped generate and thus had little private incentive to generate profits. Perhaps the conference commissioners were paid so poorly that the perks and kickbacks they got from the bowls actually were more profitable to them individually, so they preferred the old system. One side effect of the fact that conferences are now sharing their profits with their commissioners (all of the major commissioners now earn over $1 million per year) is that they are less likely to act against the conference's financial interest for a free room on an $899 booze cruise.

11 For my own distaste for the BCS system, see my ESPN editorial.

Andy Schwarz is an antitrust economist and partner at OSKR, an economic consulting firm specializing in expert witness testimony. Follow him on Twitter, @andyhre.

Image by Sam Woolley.