On Thursday, the national basketball team of Ireland beat Andorra, 63-56, to stay alive in FIBA’s European Championship for Small Countries, held all week in Serravalle, San Marino.

The win came in the final game of the group stage of the tournament, and a day after an 11-point loss to Malta, a squad led by 7-foot-5, 320-pound Samuel Deguara of Mono Vampire of Thailand, had the Irish teetering on elimination from the tournament. But Ireland will now face Norway in the semifinals on Saturday, a win-or-go-home game. And that means Pete Strickland’s story lives on.

The Irish national squad, a historically woeful outfit representing a country of 4.5 million folks whom almost to a man or woman don’t give a rip about basketball, is currently coached by Strickland, a lovable Yank with a cinema-friendly story if there ever was one. Think Hoosiers meets The Quiet Man, with some hints of The Hangover. As a young man, you see, Strickland devoted two years of his life trying to make Ireland care about the game, and briefly succeeded. Decades later, he was asked to take another shot, and now, at 60 years old, he’s taking it. A title for the Irish here, longshot that it is, would give Strickland’s story the happy ending Hollywood loves.

Nobody is confusing the San Marino tournament with that other international sports extravaganza currently taking place on pitches in big stadiums all over Russia: All games of the Small Countries competition are played at place called Arena Domus, so small it could pass for an American middle school gym, yet even with free admission the bleachers were nowhere near filled for any group stage games. FIBA is streaming all contests live and without charge on its website.

But folks from anywhere, even those who don’t innately crave the hardwood game, can be heartwarmed by Strickland’s Irish basketball tale. It’s a sweet story full of clashing cultures, booze, youthful breakups and middle-age makeups. And, sure, basketball. Lots of basketball.

Strickland is not Irish; he was born in New York and grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, where he still lives. But Strickland has always loved basketball as much as anybody loves anything, and learned to also love Ireland after basketball brought him over there in 1980. The former Pitt point guard emigrated to Cork to play for the Neptunes, a team in the Super League, a national professional confederation. Strickland stayed only two years, but while there he became a pivotal figure in launching a brief and bizarre basketball boom all over Ireland, the only era of relevance the game ever had in the history of the country.

While Strickland was no slouch during his playing days in the U.S.—he left Pitt as the school’s all-time assists leader—he was nevertheless used to being surrounded by greater players. He went to high school in the mid-1970s at DeMatha Catholic, a Hyattsville, Md., prep that for decades has been second to none in producing hoops talent, and while there played alongside such phenoms as NBA Hall of Famer Adrian Dantley and future All-American college players and NBA first-round picks Kenny Carr and Charles “Hawkeye” Whitney, as well as current Notre Dame head coach Mike Brey.

But even if he didn’t stand out at home, Cork had never seen anything like Strickland. Hanging From the Rafters, a retrospective of Ireland’s basketball boom, has a chapter devoted to Strickland, who author Kieran Shannon wrote had immediately upon his arrival wowed the Neptune fans who packed Parochial Hall in Gurranabraher by showing he “could handle the ball like Hendrix could handle a guitar.” Early in his first season, he was asked to take over as coach of the team, while still serving as the starting point guard.

Shannon’s book also explains how the young foreigner won over lots of Irish sportsmen by taking on a sort of Johnny Appleseed role and spreading the American game throughout the Emerald Isle. Strickland volunteered most of his free time toward giving clinics to lots of folks who’d never dribbled a basketball before.

“Pete became a missionary, a basketball missionary,” Shannon told me. (The 2013 documentary, We Got Game: The Golden Age of Irish Basketball, is based on Shannon’s book.)

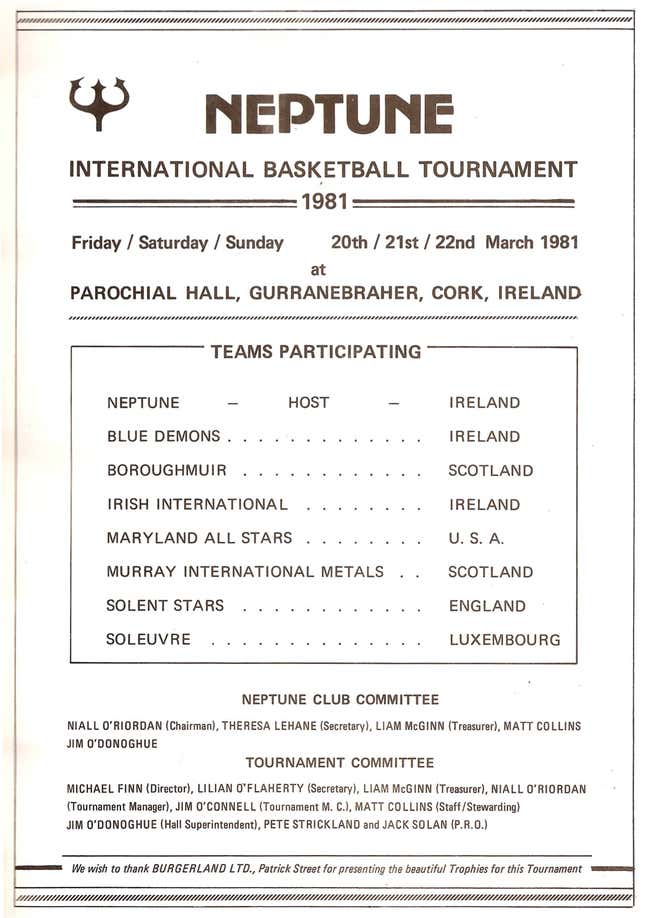

Strickland’s brightest, shiningest moments in helping inspire the hoops boom, and the primest reason his basketball biography teems with cinema friendliness, came from his role in the inaugural Neptune International Basketball Tournament in March 1981. Strickland’s first year in Cork had been such a hit with locals (Shannon insists the title to his basketball tome, Hanging From the Rafters, came from him seeing fans literally hanging from the rafters inside the overstuffed gym at Neptune’s home games) that club management decided that the city was ready to host squads from all over for a global exposition. Neptune officials got commitments from middling clubs from England and Belgium and around Europe, plus the Irish national team and Neptune’s crosstown rival, CC Blue Demons, and convinced Burgerland, Cork’s only burger joint, to promise to bankroll the event.

But the bosses told Strickland that the sponsorship money, and the fate of the whole shebang, depended on whether a squad from America showed up—and made it clear that it was up to him to deliver one. Despite their believe in his basketball powers, the truth was Strickland had no great connections to American basketball.

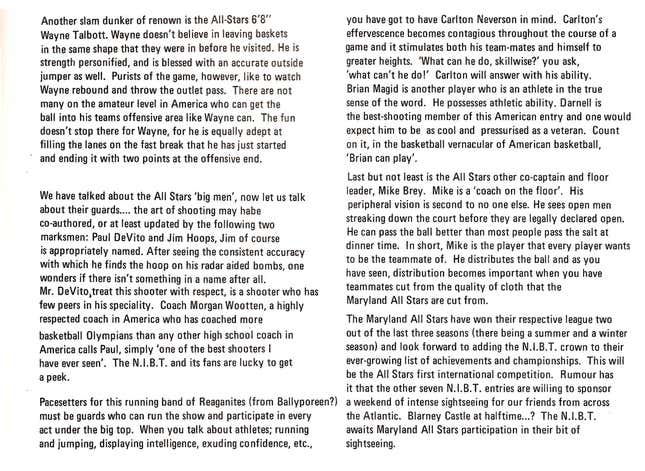

So the only way he met his obligation was by calling up a bunch of high school buddies he’d played with or against during his days at DeMatha and asking if they’d cross the pond and pose as American basketball stars. In exchange, they’d all get a free trip to Ireland. Soon enough, he’d assembled a passably talented squad, which included Brian Magid, a former high school All-American guard who’d played at the University of Maryland and George Washington University before being drafted in 1980 by the Indiana Pacers, and, Brey, his DeMatha teammate who at the time was playing for G.W. and still had a year of college eligibility left.

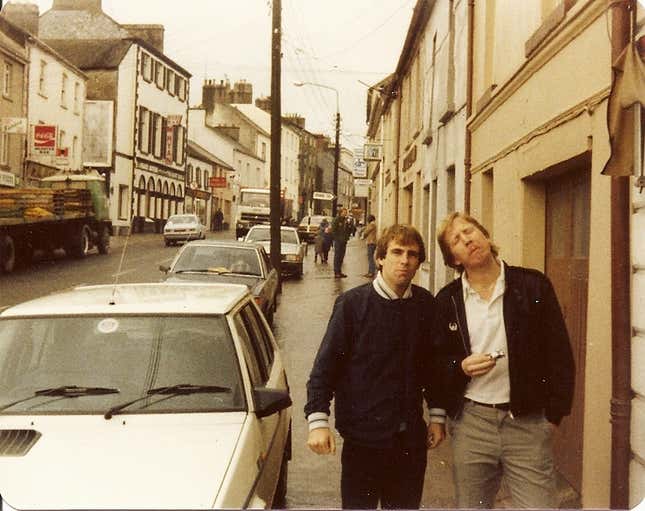

Strickland’s pals arrived together in Cork on St. Patrick’s Day and, despite spending the night power-drinking all the way across the Atlantic, immediately found themselves marching as the guests of honor in a parade before a crowd of townspeople that Magid estimated to number in the hundreds of thousands. One of the inebriated invaders, former D.C. Catholic League and Jacksonville University sharpshooter Paul DeVito, hurt his back running into a parade float so bad he had to be scratched from the tournament. (DeVito recalls, however, that his injuries did not prevent him from continuing drinking during his Irish excursion, and that memory is seconded by several sources.)

The official tournament program billed the U.S. team as the “Maryland All-Stars,” and described the squad as a “running band of Reaganites.” The Americans were tagged in the brochure as the tournament’s obvious “favourites,” alongside a claim that the squad had captured league championships in “two out of the last three seasons,” led by Brey, described as the All-Stars’ “coach on the floor.” In truth, there were no championships or even any leagues that this bunch was a part of. “We met for the first time at the airport,” Magid told me some years ago. “We never played [together] before Ireland.

Despite their lack of time together and their by-all-accounts ceaseless alcohol intake, the Maryland All Stars still whupped the Irish national squad to set up a match with Cork squad CC Blue Demons in Parochial Hall, which was packed with provincial fans to a hanging-from-the-rafters degree. The All-Stars were up by just two points with a few seconds left when a jump ball was called in the Blue Demons end of the court. A guard for the Cork club, John Cooney, got the tip and fired up a three pointer that went in as the buzzer sounded. The Americans were out of the tournament, and the locals went absolutely bonkers. Brey now recalls that “the people in Cork thought they beat Team USA.” (When Brey returned from Cork, he was suspended by the NCAA for the first three games of his senior season at G.W. for playing in a tournament against professionals.)

Steve Karr, a grad assistant for the team at G.W. when he answered Strickland’s call to cosplay a basketball player, told me the loss, and the locals’ reaction to it, only made the trip more memorable. “The Irish people treated us like we were great even though we weren’t,” Karr says “It was the only time I ever felt like a star.”

Tournament organizers were originally pissed at the result, thinking that no fans would show up once the Yanks were bounced. “They’re going, ‘Pete, you told us these guys were good! What happened?’” Strickland told me. But it turned out that having the foreign power at the hand of a homegrown hero like Cooney was great for business, not just for the rest of the tournament, which sold out, but for the game of basketball all over Ireland. Cooney’s shot was put on the cover of Basketball Ireland, the national basketball magazine. The sponsors were so happy they bought into the club, and changed the name to Burgerland Neptune, which went on to play before sell-out crowds (particularly in any derbies against Cooney and CC Blue Demons) and win several championships throughout the ‘80s and become recognized as the most successful squad in Super League history. By the end of the decade, the club had built the first team-owned arena in all of Europe—Neptune Stadium. And CC Blue Demons got sponsored by a major soft-drink company, Britvic, thereby becoming the first Super League team with a national sponsor. The way Shannon, Ireland’s premier hoops historian, sees things, these advents all can be traced back to Strickland’s efforts to grow the game, including the serendipitous or brilliant strategy to recruit an American squad that served as fodder for the locals for the fateful Cork tourney.

But Strickland wasn’t around for basketball’s glory days. Not long after Cooney’s big shot dropped, Strickland began squabbling with the new Neptune ownership over the increased meddling in personnel matters, highlighted by Burgerland’s refusal to honor agreements made with American players he’d recruited for his second Super League season. By 1982, he was back in the U.S. and on his way to a long career as an NCAA assistant or head coach. As Strickland’s career thrived, with stops at D1 programs including Coastal Carolina, Virginia Military Institute, Old Dominion, Dayton, and North Carolina State. In 2013, he left his last gig as chief recruiter on Head Coach Mike Lonergan’s staff at G.W., and expected retirement to kick in.

While his career thrived in his home country, the game he’d strived to promote as a lad in Ireland had withered and all but died there.

But in 2016, Strickland took a call from an old pal from Cork, Francis O’Sullivan, a teammate of his on the 1980 Neptune squad and a guy he’d stayed in touch with through the years. O’Sullivan told him lots of folks with Basketball Ireland, the national sanctioning body, remembered him and his role in the boom years and wondered if he’d be interested in coming back across the Atlantic Ocean if the national team job was offered. He was told the job would be to put together and prepare a team for the 2018 European Championship for Small Countries. He said he’d consider it, and a formal offer followed.

Some signs of the hoopsless situation in Ireland: Not one player now in the NBA is from Ireland. Only one Irish native has ever made the league: Pat Burke, who was born in Dublin, but moved to Cleveland as a tot and grew up in the U.S. Correspondingly, the Irish national team has a really bleak past. Only once has an Irish team made an Olympic appearance. The Irish came to the 1948 London Games, with a roster made up mostly of army veterans battle tested by WWII but with no basketball experience. The team proved to be not just a national embarrassment but an international punchline. The Irish arrived in London without uniforms, went 0-5 and were outscored 336-82, good for 23rd place in the 23-team tournament. The Irish have avoided all Olympiads since. The men’s national team was abolished entirely by Basketball Ireland in 2009. FIBA scuttled the Irish group’s effort to revive the national team in 2013, citing an old debt Basketball Ireland owed the Switzerland-based sanctioning body.

But as Strickland thought about taking over the national team, he wasn’t dwelling on the things like the post-war Olympics debacle or looking for any old debts to be repaid from the back-in-the-day brouhahas with burger magnates that ended his first stint in Cork. When he thought back to his initial run with Irish basketball, it was that glorious rookie year with Neptune, full of adoration from the locals and teaching kids what dribbling was and, sure, the drunken shenanigans of the Maryland All-Stars. That run may have ended on a sour note, but the national team job, coming all these years later, offered the hope of giving his Irish basketball experience another, much more pleasant coda. He took the offer in November 2016.

And the Irish have been treating Strickland like a hero all over again. He’s been honored twice at the Irish embassy in D.C. since taking the Basketball Ireland job, and was named Gael of the Year for 2018 by organizers of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in the Nation’s Capital. That meant Strickland served as a guest of honor at a St. Patrick’s Day parade; though, unlike that last time in Cork, nobody in Strickland’s entourage obviously overimbibed or ran into a float.

And now more deja vu from ‘81: Strickland finds himself in another international tournament with the future of Irish basketball depending on the performance of a team he organized. A win for the Irish in San Marino could be as important to the game in Ireland as that loss by the Maryland All-Stars was back in the day. And, again, it’d give his basketball diary such a climactic ending. I texted Strickland after the Andorra game and asked if he had any thoughts about the implications the win had on his own story.

“Storybook STILL ALIVE!” he texted back.