Thirty years ago this spring, Bob Irsay, the prototypical bad sports owner and an obstreperous public drunk, moved his Baltimore Colts to Indianapolis. His son, Jim Irsay, the current Colts boss, has sucked the fun out of the anniversary for Indianapolitans with a scandal that, in its sad and sordid way, offers a sort of tribute to his old man. Meanwhile, in Baltimore, any residents old enough to remember back that far will never forgive the elder Irsay for his semiconscious uncoupling of their city and his Colts, even though he's been dead since 1997.

Instead, we'll dedicate this anniversary to the brothers of Sigma Chi, Gamma Chi chapter, maybe the only people who remember the move fondly today. They were Irsay's moving crew, the dudes who did the physical work of relocating an NFL franchise, who bubblewrapped a bogus Vince Lombardi Trophy and desecrated Art Schlichter's jersey and snuck off with some Colts memorabilia. The role they played was large and largely forgotten: USA Today, in one of the larger retrospectives on the move published recently, gave all the credit to the Hell's Angels. Like hell! The only gang that moved the Colts was one made up of frat boys from the University of Maryland.

"It really could be a movie," says Duffy Welsh, a fraternity member and one of the Mayflower mercenaries. "I remember so many scenes of that night. Just crazy."

Thirty years later, with Bob Irsay dead and Jim Irsay in disgrace, it's time we find out a little more about that move. Who were these frat boys doing Irsay's bidding? What did they see on that dark night of the Baltimorean soul? And did anyone actually make off with Frank Kush's pants?

William Hudnut was mayor of Indianapolis at the time. He was previously a Presbyterian minister and a one-term U.S. congressman. He'd made development of the downtown the focus of his mayoral administration. The centerpiece of his plan was the RCA Dome, an $80 million stadium that Hudnut convinced the locals to build, largely with tax revenues, in the hope that it would butch up Indy's milquetoast image and land the city an NFL team. He put Indianapolis's name in the hat alongside Phoenix, Jacksonville, and Memphis when he heard the Colts might bolt Baltimore, and he buddied up with Irsay, a man his own mother described to Sports Illustrated as "the devil on earth."

Hudnut's next-door neighbor, an Indianapolis native named John B. Smith, quickly offered to lend a hand, and some wheels, if that would help bring Irsay's Colts to Indy. Smith was in a unique position to assist: His grandfather, Burnside Smith, had run Mayflower Transit beginning in the 1920s and turned it into one of the world's biggest moving companies, and Johnny B., as he was known around town, had risen to chairman of grandpa's company.

"We had a conversation to the effect that when the time came, if it came, he would move the franchise for free, pro bono, for the city," Hudnut says.

Hudnut told Mayflower to stand by. He remembers getting a call from the Colts' general counsel, Mike Chernoff, just before noon on March 28, 1984, with news that the Maryland legislature was on the verge of passing a bill that would give the city of Baltimore the right of eminent domain over the Baltimore Colts, and that the governor would sign such an edict. If he really wanted the Colts in Indy, Chernoff told Hudnut, say the word right now. Hudnut said the word. Chernoff "said they had to get out on short notice because if the governor signed it and made it law they'd be tied into litigation," Hudnut says. "So I called Johnny B. and he got his vans on the road."

But the team still needed bodies to load up the Mayflowers. Enter the frat boys.

Joe Ponzo, then a junior at Maryland and a Sigma Chi brother, remembers hearing the phone ring on the second floor of the frat house on the College Park campus and taking the call from a Mayflower supervisor that got it all started.

"We had a lot of guys who worked part-time for Mayflower, and they said they needed a lot of people that night and they were paying $10 an hour," says Ponzo. "So I went to the lunch room and told the guys. Everybody said no. So I go back to the phone and he said he'd go to $15. They said no again."

Ponzo says he had too much schoolwork to take on any moving job, but he bargained hard on behalf of his brothers and ultimately goaded Mayflower into upping the rate to $20 an hour—"paid in cash," he says. (In today's dollars, that's $45.48 an hour.) The Mayflower recruiter would not give Ponzo any details about the move other than the pay and an order to be ready at 11 p.m. for a bus to pick them up. A horde of Sigma Chis signed on anyway. No official count has ever been made by the frat, but estimates on the size of the Sigma Chi contingent range from a dozen brothers to 20.

Even after they'd boarded the bus alongside several veteran Mayflower movers and decamped for College Park, the brothers weren't told where they were going. That level of secrecy seems unnecessary, given that this was years before cellphones and social media. But the unknown caused the youngsters' minds to race.

"We were thinking it had to be CIA or something in D.C.," says Welsh, whose father, George Welsh, was the longtime football coach at the University of Virginia and the U.S. Naval Academy.

But the buses headed north, away from the nation's capital. It wasn't until they turned at the exit sign on the interstate for Owings Mills that it dawned on Greg Gaston, who now hosts a sportstalk show mid-days on WHBQ-AM in Memphis, what was going on. The Sigma Chis prided themselves on being a jocky frat. They knew where the Colts headquarters were located.

Gaston recalls a little grumbling among some of the brothers once they figured things out. Maybe they should pull out of the job, someone suggested when the bus rolled up to the training center parking lot. Baltimore was only 30 miles from the Maryland campus, after all. Even though the Colts were in the dumps at that time and football fandom within the fraternity leaned far more toward Joe Gibbs's gang in Washington, which had appeared in the Super Bowl the previous two seasons, there was still some loyalty to the blue horseshoe.

"I grew up idolizing Johnny U. and his hi-tops and that buzz cut and then Bert Jones," says Gaston. "And here I am, moving the Baltimore Colts! I was moving my favorite team!"

Nobody backed out in the end. The allure of being allowed inside an NFL team's headquarters, and the money Mayflower was paying off the books, proved more powerful.

Brother Bill Kynast says he immediately snuck off to an office inside the compound in hopes of alerting the world outside that Irsay's plan was being carried out. He tried to phone up George Michael, a D.C. sportscaster whose kitschy Sports Machine show was just then getting underway. How cool would it have been to break the news to him? Hey, I'm in Owings Mills right now, and I'm moving the Colts!

"But I never got through," Kynast says, "because somebody at the main switchboard [at the training facility] kept getting on the line, and then I heard footsteps and I didn't want to get in trouble."

To a bro, the Sigma Chi members recall that the early stretches of the gig found them acting more like looters than movers, as the temps launched an intramural competition to steal the coolest Colts memorabilia.

"The place just looked like everybody who worked there, all the players and coaches and everybody, just expected they'd be back," Welsh says. "So everything's just lying out: helmets, workout stuff, cleats, clothes. And I don't remember seeing supervisors in there. So we're like kids in a candy store. Everybody was on a high. Guys were showing off the jerseys and stuff they found, and shoving shirts in their pockets."

Welsh remembers flaunting his locker-room find of a jersey belonging to Art Schlichter. He was the former Ohio State quarterback whom Bob Irsay had famously forced his general manager to take over Brigham Young star Jim McMahon with the fourth pick in the 1982 draft. It was quickly discovered that Schlichter was a compulsive gambler, almost Irsayishly dysfunctional in his way, and in 1983 he was suspended for the entire season by the NFL's commissioner, Pete Rozelle, for his involvement with a group of Baltimore-area bookies that had been busted by the FBI. At the time of the move, he was embarking on one of several failed attempts to clean up his act. (Schlichter, now regarded as one of the biggest busts in NFL history, has been in jail for most of the past 30 years and is currently housed in FCI Terre Haute, a medium-security federal prison. He's two years into a 10-year sentence for selling phony Super Bowl tickets.)

There were other scores. Gaston recalls a brother coveting Curtis Dickey's game-worn gear. "Guys put on whatever they could find, and put their clothes on top," Gaston says. "These 155-pound guys are walking around looking like 180-pounders. Like nobody could tell."

I began asking Sigma Chi members for tales of the Colts move in 1999 for a column in Washington City Paper. Hal Stein, a brother now living in the Richmond area, told me at the time that his assigned chore was to put jerseys in boxes. Instead: "It was like, one in the box, and one in my pants," Stein said.

The thievery got so bad that Mayflower management called a timeout in the middle of the night and gathered the workers in a meeting room. A company official told the crew that so long as everybody agreed to stop stealing and to pile up any illicit bounty they'd already filched in a corner of the room, Mayflower wouldn't get anybody in trouble.

Mark Updegrove, a New Jersey native, recalls watching his frat brothers, having fattened themselves on stolen Colts gear, beginning to thin out as they took advantage of the amnesty deal. The regular Mayflower staffers couldn't hide their hate for the collegians.

"All my guys from Sigma Chi, well, we looked like Michelin Men," Updegrove said. "I remember watching a friend of mine peel off more layers than an onion, and this one [Mayflower] lifer just started shaking his head with this look of utter disgust at all of us. 'That boy's got shoulder pads on! And he's got Coach's pants on! Look at him!'"

(Updegrove survived the Colts move and grew up to become a leading presidential historian and director of the LBJ Library in Austin, Texas. He hosted four of the five living U.S. presidents at the library during the recent commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act.)

Kynast now admits he was among the bloated frat boys in the meeting room to repent.

"I probably had four or five shirts on," he says. Given the chance to repent, he stripped down to "two shirts or one" and threw the purloined garments in a pile. His mates turned in most of their ill-gotten gains, also.

"I could not believe the amount of stuff that appeared in that corner," says Welsh. "It was a mountain."

The utter strangeness of the job impressed itself on Updegrove as he and his buddies broke down the Colts' trophy case, which contained baubles from the team's various NFL titles, including Weeb Ewbanks's fedora and what looked like the Lombardi Trophy from Super Bowl V. "So I'm holding these championship trophies and thinking about how great this team really was," he said. "Right away it hit me that leaving town in secret in the middle of the night just wasn't right for the Colts' fans, that what Irsay was doing was the ultimate sissy move."

That Super Bowl V trophy is a story unto itself. Turns out the Lombardi Trophy that got boxed up that night was likely a counterfeit. The original Super Bowl V statuette, the first championship trophy awarded with Lombardi's name affixed, was borrowed from Irsay in 1973 by Carroll Rosenbloom, who had owned the Colts before swapping franchises with the owner of the Los Angeles Rams (who happened to be Bob Irsay). Rosenbloom told Irsay he wanted to show off the trophy at a party he was throwing on the Queen Mary luxury liner in Southern California. The Colts shipped it west, where it remained despite Irsay's efforts to get it back from Rosenbloom. So at Irsay's insistence, the NFL made a replica Lombardi Trophy, which was kept at the Owings Mills compound until the move.

A Lombardi Trophy now sits at the Sports Legends Museum, located at Camden Yards. John Ziemann, deputy director of the museum, says this trophy was sent back from Indianapolis in 1986 as part of a settlement to end all lawsuits between the city of Baltimore and the Irsays. But he insists that nobody at the museum "can confirm or deny" if this is the original. "We don't know if the trophy is real," says Ziemann, who was also president of the Baltimore Colts Marching Band at the time of the move. However, former Baltimore Colts public relations director Ernie Accorsi told the Los Angeles Times in 2000 that offensive line coach George Young's name had been left off the inscriptions on the original, so he'd ordered that Young's name be added when the copy was made. NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy confirms the accuracy of the Times' tale. Ziemann, at a reporter's request, inspected the names on the museum's trophy and found "George Young." The frat boys, it turns out, had packed up a phony version of a trophy stolen by another team's owner. Everything about the move was a little seedy.

As night headed toward morning and the thrill of being surrounded by professional football tchotchkes wore off, the move became more like any other move. Crowds began gathering at the complex as word got around Baltimore about what was happening in Owings Mills. Fans and reporters were kept outside. Ziemann, who worked for a local TV station, watched the movers while standing among the banned. He didn't see any biker gang doing the work. "There weren't any Hell's Angels," he says. "I was outside and I saw the kids."

Some Colts employees managed to make it inside. These were the folks who would be most affected by Irsay's decisions, and the move concluded on this melancholy note.

"A receptionist came in and we're literally pulling the desk out from under her," Welsh says. "I remember feeling really sad about that when we left that morning."

The Sigma Chis did not accompany the Mayflowers to Indianapolis. The boys got back on a bus and pulled into College Park around sunrise. None of the choice memorabilia they'd toyed with in the night made it back to the frat. Instead, the only goods that the brothers will now admit to having brought into the house were Baltimore Colts stickers and matchbooks, a Colts welcome mat, a deflated football, and a trucker hat belonging to the team's loathsome and tyrannical coach, Frank Kush.

The legend among the Sigma Chis was that someone had made off with Kush's pants, not his hat. Alas, that appears not to be true. The hat would have to suffice as a token of fan vengeance. Kush's record in Baltimore was horrible (7-17-1 in the two seasons prior to the move, including a winless, strike-shortened 1982 campaign), and his reputation was even worse. John Elway disliked Kush so much that he threatened never to play in the NFL unless the Colts, who'd drafted the Stanford QB and future Hall of Famer with the top pick in the 1983 draft, traded him. So they traded him. Nobody other than Irsay was more responsible for the demise of the Baltimore Colts than Kush.

So what kind of human being would covet a cheap polyester cap stained with the body fluids of that guy?

A college kid.

"I had Frank Kush's hat," says Kynast with a laugh. "I loved that hat!"

Kynast says he held onto the keepsake long enough for trucker hats to become fashionable again, but lost track of it at some point in the new millennium, just as he's lost track of almost all the other loot from Sigma Chi's pillaging of Owings Mills through the years. A recent search of the basement turned up only a frayed sticker reading "Baltimore Colts Season Ticket Holder." The sad sticker remains stuck to a wooden note-card holder that he found stuffed in a box alongside other detritus from his college days: "Sigma Chi T-shirts, a pair of Jams, and Vuarnet sunglasses," Kynast says. The Colts sold just 23,000 season tickets the year before the move, so lots of excess stickers were lying around the team's headquarters in the spring of 1984. The kids knew Indy wasn't going to have any use for 'em.

Hudnut, 81, now teaches grad students at Georgetown University. He makes a point each semester of recounting without apology how he landed a football team for his city 30 years ago. When he was named to head up Georgetown's real estate studies program last year, the school illustrated the announcement not with a portrait of Hudnut but with a photo of the 2007 Super Bowl ring that the Indianapolis Colts had given him. He remains proud of his role in bringing a team to Indy, even if it meant one was ripped out of Baltimore in the middle of the night.

"Indianapolis didn't steal the Colts," says Hudnut. "Baltimore lost the Colts."

Gaston is similarly comfortable with his choices. He would move his favorite team all over again, too, alongside his Sigma Chi brothers. "They were going to move with me or without me," he says. "Why not be a part of it?"

Kynast's views on that night have evolved over time. He says he had no qualms about his frat's place in sports history for years after college. That changed when he moved to Cleveland for work, after Art Modell's Browns had deserted their fans for Baltimore in Colts-like fashion.

"I remember being in the bathroom of a bar that had a picture of Art Modell in the urinal," he says. "So I'm standing there, aiming at him, and I'm thinking, 'I worked for Mayflower when we moved the Colts.'"

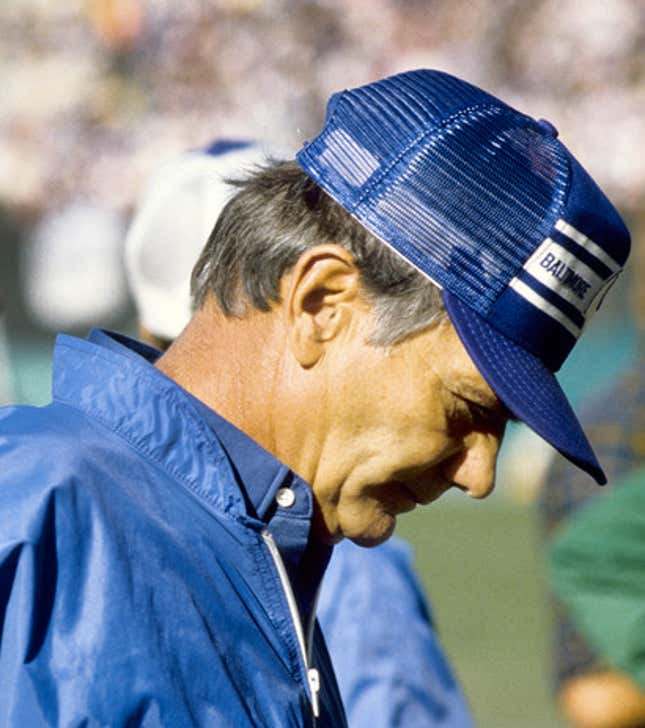

Image by Jim Cooke