Nearly 30 years ago, on the day before he was to play for a national championship, Andrew Gaze was on the defensive.

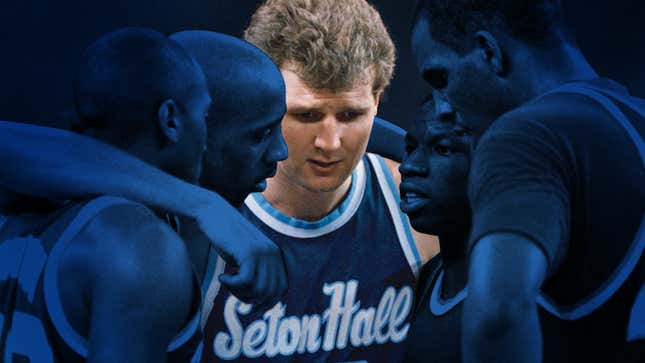

A native of Australia, Gaze was 23 years old. He had already played in two Olympics, and he had already been a dominant force in Australia’s semi-pro league. He enrolled at Seton Hall the previous fall with the intention of staying for one year—and one year only, though the school did make an effort to try to get him a second year of eligibility. This being the era when college players at big-time programs were expected to stay in school for three or four years, press accounts of Gaze frequently referred to him as a “mercenary” or a “ringer” or a “hired gun.” And so, on the day before Seton Hall’s Pirates were to face the Michigan Wolverines in the 1989 title game at Seattle’s Kingdome—seven months before the NCAA signed its first $1 billion agreement for broadcast rights to its men’s basketball tournament—Gaze sat through a pre-game press conference filled with questions about his intentions as a student-athlete.

“If the credits were useless, I wouldn’t be here right now,” Gaze said that day, according to the Hartford Courant. He later added, “It would be stupid to say I’m not here for the basketball.”

It would be stupid to say Gaze was not there for the basketball, even to this day. But it nonetheless caused something of a furor after Seton Hall lost that title game by one point because of a controversial foul call in the waning seconds, and then four days later Gaze got on a plane and flew back to Melbourne for good.

“I can understand why they would have to look at it,” Gaze told me recently by phone from Australia. “But it was all hunky dory. There was no deceit or anything like that.”

Gaze didn’t go straight to the NBA, and a few others before him had jumped to the old ABA after only one year. But this is the story of college basketball’s first true one-and-done.

Gaze literally grew up in a gym. His father, Lindsay Gaze, had a lengthy career as an international player and coach, and is now in the Naismith Hall of Fame. Lindsay Gaze was also the longtime general manager of the Victorian Basketball Association, an AAU-like development program. When Andrew was growing up, the family’s home was in the official GM’s residence, which was attached to a nine-court facility used by the Melbourne Tigers, the club team Andrew played for (and Lindsay coached) both before and after his stint at Seton Hall.

“You go out my back door, and you’re basically in the venue,” Andrew Gaze, now 51, told me. “I can’t remember a day in my life without basketball because I was born into that environment.”

Gaze went on to become the greatest basketball player in Australia’s history. A sharpshooting 6-foot-7 small forward, he was also a gifted passer and defender. “Andrew was just far superior to most kids his age in terms of not only shooting, but experience and also basketball IQ,” John Carroll, a Pirates assistant coach at the time, told me.

Gaze is a five-time Olympian, a FIBA Hall of Famer, a 15-time National Basketball League first-teamer, a seven-time NBL MVP, and a two-time NBL champion. He even played parts of two seasons in the NBA, winning a ring as a deep reserve for the 1999 San Antonio Spurs, for whom he averaged three minutes over 19 games. These days, Gaze is the head coach of the NBL’s Sydney Kings.

Hey, here’s Gaze starting a little scuffle by cheap-shotting Vince Carter during an exhibition tune-up before the 2000 Olympics:

P.J. Carlesimo was aware of Gaze by the time the Australian National Team came to the U.S. in 1986 to play a handful of exhibition games against Big East schools. And before Gaze had finished tearing through several of the league’s teams with 40-point performances—including 46 points against Seton Hall, the team Carlesimo coached—Gaze had Carlesimo’s full attention.

“I mean, it was ridiculous,” Carlesimo, the future NBA head coach and current television analyst, told me. “He [scored 40-something] like four times in eight days. I just had a hunch he could play in the league.”

Understand: The Big East at this time was college basketball’s premier conference. Between 1982 and 1990, all but one of the league’s nine teams would make it to a Sweet 16. Six would reach a Final Four. Three would be national runners-up, and Georgetown did it twice. Two would win the whole damn thing. But in ’86, Seton Hall was still the absolute dregs of the league. A tiny, diocesan Catholic school situated in South Orange, N.J., between the urban blight of Newark and the wealthy sprawl of Maplewood, Seton Hall had little tradition to draw from. The Pirates won the NIT in 1953—when winning the NIT was actually considered a bigger deal than taking the NCAA—but that was ancient history. Their on-campus gym still had a stage just behind the baseline at one end. Bill Raftery coached the Hall from 1970-81, and he barely won more games than he lost. An April 1989 Newsday story described Seton Hall during the Raftery era as “essentially a commuter school where students left the concrete campus at 3 o’clock to get to the jobs that kept them in school.”

There was even a time when students at other Big East schools would contribute to the Pirates’ booster club so as to snap up Seton Hall’s unused allotment of Big East tournament tickets.

By 1985-86, the Big East was enough of a draw for Seton Hall to move its conference home games to the Meadowlands Arena in East Rutherford, right next to Giants Stadium. It was Carlesimo’s fourth season. His first winning campaign wouldn’t come until a year later. But soon after Gaze wowed them during that ’86 tour, Carlesimo, Carroll, and athletic director Larry Keating had Gaze on their radar.

“He was one guy that I kind of earmarked that might come to the States,” Carroll remembered.

Keating remembered Gaze telling him, “Well, we’ve been coming here for a couple of years now, and you’re probably the 10th school that has said the same thing to me. And none of the other nine ever followed up.”

The following summer, it was Carlesimo’s turn to coach a team of Big East All-Stars on a tour of Australia. And because Big East commissioner Dave Gavitt had a scheduling conflict, Keating went too.

“Totally coincidentally, by the way,” Keating, now a special assistant to the AD at Kansas, told me. “It had absolutely nothing to do with the fact that we were recruiting Andrew.”

The Pirates made their pitch, but Gaze was dead set on playing for Australia in the 1988 Olympics, and he wanted to spend the year preparing with his teammates. But Carroll, who would later coach the Boston Celtics on an interim basis, never gave up. He spent the next year calling Gaze regularly—not the easiest task in those days, considering the cost and the 14-hour time difference.

“You know what it took just to make one phone call to him?” Carroll remembered. “That’s all I ever did. Because I knew what it would have meant if we got him. I knew it.”

“John Carroll was just super persistent,” Gaze recalled.

Gaze had already completed two years at the Footscray Institute, which is now Victoria University. But he missed a lot of schooling in the run-up to the Olympics, and he and his parents saw what Seton Hall was offering as a chance to get in two semesters of course work while also competing at American college basketball’s highest level.

Gaze just wouldn’t be able to enroll until after the Olympics. Which, for Gaze, didn’t end until a loss to the U.S. in the bronze-medal game on Sept. 29, several weeks after the fall semester began.

Gaze was listed as a junior upon his arrival at Seton Hall that October. He joined a senior-laden Pirates team that had earned the school’s first NCAA bid the year before. The NCAA that year allowed athletes who competed in the Seoul Olympics to skip the fall semester but to continue to play their chosen sport. Gaze and Pirates big man Ramon Ramos, who played on Puerto Rico’s Olympic team, decided to enroll in their fall classes anyway, even though they were several weeks behind.

(I pause here to note the NCAA’s arbitrary adherence to the concept of the student-athlete in cases like these. This was the same NCAA that a few years earlier had passed Proposition 48, which took a year of eligibility away from athletes who failed to achieve certain academic benchmarks including minimum scores on standardized entrance exams—a rule that disproportionately affected black athletes. Yet here was the NCAA allowing athletes to compete even if they weren’t going to class. More on this later.)

Gaze seemed to fit right in with his veteran teammates, but in the beginning, his naturally laid-back nature caused him to be a bit gun-shy.

“He came over, and for the first, like, 10 days, he literally never shot the ball in practice,” Keating said. “He was so concerned about fitting in with these four seniors who owned the thing and it was their team. Finally after about a week, P.J. pulled him aside and said, ‘Andrew, what the hell are you doing? You are the best shooter on the team, and maybe the best in the country. You gotta shoot the ball.’ As soon as the other guys realized it they told him, ‘Yeah, we need you.’”

The Pirates got off to a fast start, opening the season at the Great Alaska Shootout with wins against Utah, Kentucky, and defending national champion Kansas—Roy Williams’s first loss as a head coach. The Hall ripped through its non-conference schedule with a 12-0 record and had risen to No. 10 in the polls when it defeated No. 5 Georgetown in the school’s first-ever sellout at the Meadowlands. As the season wore on, Gaze’s scoring prowess would reveal itself—but only sometimes. The Pirates had four double-figure scorers, led by guard John Morton, who would be a first-round pick that summer for the Cleveland Cavaliers. They also played ferocious interior defense, a prerequisite for survival in the bare-knuckle Big East of the 1980s. All that balance meant that one night, Gaze might score 17 points in the first 10 minutes. Another night, he might barely score at all.

“We kind of had a team,” Carroll told me. “The addition of Andrew made us a great team. And I don’t mean that Andrew made us great; there were certain missing parts, and he helped fill in one of those missing parts.”

The Pirates would remain in the Top 15 the rest of the way. Though picked to finish seventh in the Big East by the league’s coaches, they ended the regular season in second place. Three of their six losses entering the NCAA tournament had come against Syracuse.

Seton Hall went into the tournament as a No. 3 seed in the West Region. After grinding out wins against Southwest Missouri State and Evansville, the Pirates took out No. 2 seed Indiana in the Sweet 16 by limiting the Hoosiers to three field goals in the final 15 minutes. They got No. 4 seed UNLV in the regional final after the Runnin’ Rebels knocked off top-seeded Arizona. Gaze had 19 points, five rebounds, three steals, and two blocks against UNLV. Defensively, Gaze was charged with sticking Stacey Augmon, one of UNLV’s all-time greats; he limited him to 4-for-12 shooting. The Pirates pulled away in the second half for a remarkably easy win. Gaze was named West Regional MVP.

All the while, Gaze was becoming a sensation, both in the U.S. and back home in Australia. News reports were heavy with clichés likening Gaze to Crocodile Dundee, while at least one television report ran B-roll overdubbed with the ’80s Australian band Men at Work.

“The thing blew up in Australia,” Keating said. “He became a legend.”

In the national semifinals against Duke, Seton Hall fell behind 26-8, only to roar back after a Duke freshman named Christian Laettner got into foul trouble, and another starter, Robert Brickey, badly bruised his thigh. The Pirates were too quick for the Blue Devils, and Gaze scored 16 of his team-high 20 points in the second half. Seton Hall won, 94-78, setting up a date with Michigan in the title game.

That game is best remembered for the ticky-tack foul referee John Clougherty called on Seton Hall point guard Gerald Greene (No. 15 in white) with three seconds remaining in overtime. Freshman Rumeal Robinson—who made just 64 percent of his foul shots during the regular season—famously drained two free throws to give the Wolverines an 80-79 win.

Gaze told me he was disappointed by the call, but that he never really took the time to reflect on it or to even watch it again until Seton Hall sent him a 20th anniversary DVD a few years back.

“I was more angry 20 years later than I was at the time,” Gaze said. “Having seen it again, in hindsight, it shook me for a fair amount of time. It’s almost like there was this epiphany of what would have been. Like, what would have happened if that decision hadn’t been made?”

Gaze told me that when he was back in the U.S. a few years later for another exhibition tour with the Australian team, he played a game that was officiated by Clougherty, and that Clougherty approached him and told him he had made a mistake by calling that foul on Greene.

“I told him, ‘Oh, no worries, mate,’” Gaze told me. “I thought it was very classy of him to say that.”

Two years ago, just before he retired as the ACC’s supervisor of officials, Clougherty made a similar admission to the Raleigh News-Observer.

“Given the timing of the situation and the magnitude of the game, would I have been better off to hold the whistle and see how the play finished?” Clougherty said. “Yeah. And I don’t run away from that.”

Seton Hall’s title-game loss to Michigan was on April 3. On April 7, Gaze flew back to Australia. On April 14, the New York Times did some patrol work on behalf of the NCAA by publishing a story in which the general manager of Gaze’s Australian club team admitted the club had paid $25,000 into a trust fund for Gaze the year before. The story, written in that classic Timesian tone of detached finger-wagging, purported to “raise questions about amateur and professional distinctions and the recruitment of top international talent into major-college sports programs.”

The morning the story dropped, John Carroll took a train to Philadelphia for a second interview for the vacant head coaching position at Penn.

“I was, like, well, I guess I’m not getting this job,” Carroll told me, though he did wind up getting hired at Duquesne a short time later.

The details about the trust fund remain murky; there was never any corroborating evidence of what the fund was used for, or even whether any of the money was used at all. But as was true of all potential NCAA scandals at that time, most of the coverage was refracted through the prism of the sanctity of the NCAA rule book: The Times quoted Gaze as saying the money was “more like expenses,” with Lindsay Gaze saying neither he nor Andrew touched any of the money, while Keating, Seton Hall’s AD, later told Newsday that Lindsay Gaze had assured him the fund was for expenses used to run the club team. Even today, in our recent conversations, Gaze, Carlesimo, Keating, and Carroll all assured me that no rules had been broken, and that Gaze was a model student. In the end, nothing happened, no punishments were handed down, and the story faded into the ether.

The subject still gets Carroll all kinds of fired up.

“I know guys who have finished the NCAA tournament on a Saturday or a Sunday, and they’re out of Dodge on Monday,” Carroll told me. “What’s the difference between Andrew and a fifth-year player now, who transferred—a fifth-year graduate student? Don’t you think those guys are rent-for-hire players? Your next story ought to be about how many of these guys who are fifth-year players actually stay for their second year and get their degree. That’s a fucking joke.”

There’s a direct parallel to be drawn between Gaze’s situation and the current discussion about one-and-dones in college basketball. Gaze wasn’t aiming for the NBA draft in 1989, but he did get to define his own experience as a college athlete—an avenue the NCAA typically only keeps open for everyone but the athletes themselves. The same athletes the NCAA refuses to compensate because of its attachment to a false premise of amateurism.

Gaze insisted to me that he earned credits during his brief time at Seton Hall, and that he never would have enrolled had it not been for those credits. A spokesman for Victoria University confirmed to me that Gaze did eventually earn his degree, in 1996, some seven years after he blew out of South Orange. But that was never the point. What was the point was that Gaze got to parlay the experience he had playing against top-flight U.S. college competition into an incredibly successful career as a professional basketball player back in Australia. And there was never anything wrong with that.

The NCAA tournament now brings in $770 million each year just from television rights. That number will climb to $1.1 billion in 2025. Even in 1989, when Gaze was putting teams coached by Bob Knight, Jerry Tarkanian, and Mike Krzyzewski in the trash can in succession, the tournament was a multi-million-dollar cash cow. And even as Gaze was being held to some phony amateur ideal, he and his teammates spent the entire duration of their three-week NCAA tournament run away from campus. Because the NCAA decreed that the Pirates had to play in Tucson, Denver, and Seattle, Seton Hall decided to stay on the West Coast until it was finished playing basketball. Classwork? Well ...

Here’s the Boston Globe, from April 4, 1989:

Carlesimo then maneuvered into a lengthy discussion of Seton Hall’s commitment to academics, noting that center Ramon Ramos was the Big East’s academic player of the year. Carlesimo said players attend study hall two hours a day, four days a week, and a tutor has accompanied them during the tournament.

Given their location in the hub of the Big East conference, the Pirates are able to travel to and from games at night, thus rarely missing class time during the regular season, according to Carlesimo.

“These kids, I guarantee you, have missed less class than any team in the country playing at this level of competition,” he said. “It’s probably safe to say that they put more time into their academics than into their basketball. Every one of our kids is going to graduate.”

Who’s to say whether any of that was bullshit? According to Keating, every player but one from that 1988-89 Seton Hall team eventually earned his degree. After all, Seton Hall likely did do everything by the book. As a former NCAA official told me, on the condition of anonymity, “Back then, I can tell you for certain, that if Seton Hall found a guy from Australia, and they got him in for one year, and he was really good, that wasn’t an NCAA issue—it was a Seton Hall issue. They probably found a way around a rule, which every school does every single day.”

That Gaze was an international player—the Boston Globe in 1990 estimated that there were “approximately 135 foreigners from 36 nations playing NCAA basketball” back then—made the situation that much more difficult to define and regulate. How would anyone categorize the education he got in Australia? How might the courses he’d take in the U.S. match up? Should he have to take a standardized test?

“All of those things were just kind of blossoming at that point,” the ex-NCAA official told me. “What happened—and what continues to happen—is there are a set of rules and regulations, and every school is looking at those regulations and saying, ‘OK, how do we not violate them, but get an advantage over the school down the road?’”

This is the kind of dissonance the NCAA requires to prop up its system. The same system that once sought to shame Andrew Gaze for asserting his agency as far as he was allowed.

Twenty-eight years on, Andrew Gaze has developed a more clear-eyed view of the NCAA. Jack Purchase, the son of his best friend, just finished his sophomore season at the University of Hawaii. Purchase’s experience in having to live according to the NCAA’s byzantine regulations has been instructive for Gaze.

“There’s an element of hardship there, that if he’s not subsidized by his parents, he can’t live,” Gaze told me. “His parents are saying it’s costing us a lot of money for him to be there, and he’s on scholarship.”

(Purchase comes from a family with means. Many other players do not.)

Gaze isn’t certain that paying players is the answer; as he put it, the current system—at least in basketball—allows smaller schools like Villanova and Gonzaga to compete with larger programs. “I think that’s one of the beauties of the entire competition,” he said. “You don’t want to compromise that, but there’s got to be a way where—some of the hardships that college players are going through is wrong.”

College basketball’s first true one-and-done understands the reality. He doesn’t need to be defensive anymore.

“The school is generating a lot of revenue out of those athletes,” Gaze told me. “Hawaii might not be; I don’t know all the ins and outs. Maybe you don’t have to make them independently wealthy, but at the very least there should be some conditions where they shouldn’t be out of pocket.”