On the same day a federal judge approved a billion-dollar settlement in the NFL concussion litigation, Rickie Harris told me a story I’d wanted to hear for a long time. It’s a legend from his days with the Florida Blazers, possibly the worst-managed franchise in professional sports history.

The Blazers played in the World Football League, which was founded in 1974 with dreams of becoming an NFL rival. The team had two owners, four home cities, and five names before it held one practice. The operation started out underfunded and, with no major network willing to anger the NFL by giving the new league a television deal, it never found enough revenues to cover expenses. Most Blazers players—a mix of NFL refugees like Harris and rookies right out of college—didn’t get paid for weeks at a time. Some didn’t get paid at all. Yet head coach Jack Pardee, forced to pay for locker room toilet paper out of his own pocket, used victimhood to bind his squad. The Blazers made it all the way to World Bowl I, the first and only WFL championship game.

The specific tale I’d been chasing for years held that just before kickoff of that big game, one of the unpaid Blazers took a stand on behalf of his penniless brothers by snatching the coin from the coin toss—-and keeping it. I’d heard long ago that Harris, the Blazers’ defensive captain, was that guy.

Yup, says Harris: “They called ‘Heads!’ and I scooped it up and said, ‘At least I get paid this week!’” We’re both laughing at the punchline.

He says the purloined coin was a 50-cent piece. (“One of those big ones.”) He doesn’t have it anymore, though, and doesn’t know what happened to it.

“But I still have the story,” he says.

“I scooped it up and said, ‘At least I get paid this week!’”

Yes, he does have that story. And, minutes after first telling it to me, Harris starts telling me about taking the World Bowl coin again, exactly like he did before—-“They called ‘Heads!’”—-with identical enthusiasm and an identical punch line and with identical laughs in identical places. A bit later, he told it all over again. He couldn’t stop.

Harris, 71, has lots of stories any sports fan would want to hear at least once. He came to the Washington Redskins in 1965, part of the earliest wave of black players on the last NFL team to integrate, and played during a golden age. In the first several weeks of his first season as a pro, he went up against such mythical figures as Jim Brown of the Cleveland Browns, Bob Hayes of the Dallas Cowboys, and Johnny Unitas of the Baltimore Colts. He played a season under Vince Lombardi, who earned naming rights for the Super Bowl trophy by being the winningest coach in NFL history. And Harris’s WFL stint, short as it was, was a goldmine of giggles.

The unconscious repetition of the coin-stealing anecdote, though, is a symptom that Harris’s stories from the gridiron came at a great cost. The same game that provided him with such entertaining and even historic material did horrible and irreversible damage to the brain where all those great stories are kept. Have just one long conversation with Harris, who counts himself one of thousands of plaintiffs in the recently settled class action suit, and you can come away envious of the ballplayer’s lot or scared that the game still even exists. Or both. His life can be used to celebrate football, or as a cautionary tale.

“I’ve got dementia,” he told me several times between wonderful recollections of a football life, many repeated again and again during the same interview. “The doctors tell me it’s blunt force head trauma. I’m usually okay if you ask me about 20 years ago; 20 minutes ago, we might be in some trouble.”

The daring young man in the flying wedge

Rickie Harris grew up in South Central Los Angeles in the 1950s. He starred at quarterback at Fremont High School, but, standing about 5’9” and weighing less than 150 pounds, even he thought he was too small to play football at the major college level. He could high-jump almost seven feet in high school even before the Fosbury Flop took hold, however, and he thought that was going to be his way out. After a stint at junior college, the University of Arizona indeed did offer him a track scholarship, but asked him to play football, too.

The coaches made him a kick returner. Harris, not entirely kidding, jokes now that he wasn’t that fast, but came to college with all the tools a return specialist would need thanks to a childhood spent running from the Slausons, a Crips and Bloods precursor among black L.A. street gangs. “It was a rough place then,” he says.

He went unpicked in the 1965 NFL draft, but Washington signed him as a free agent on the recommendation of Charley Taylor, an Arizona State alum and 1964 draftee who’d seen him return a punt for a touchdown during an ASU/UA derby. Harris says that even though he’d never planned on being a pro football player, once he got to training camp, he wasn’t going to leave.

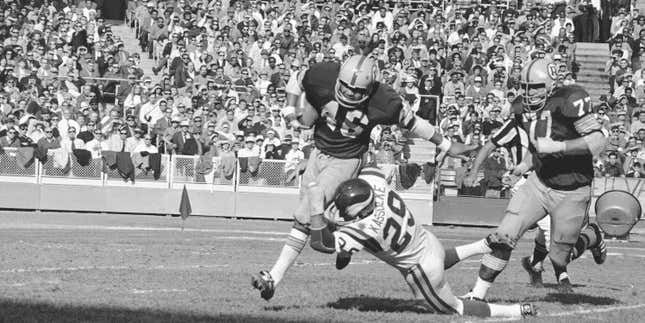

Rickie Harris brings back a punt against the Minnesota Vikings, 1970; photo via AP

Harris impressed coaches and media right away with a playing style that flaunted a total disregard for his personal safety. After an August 1965 preseason game against the St. Louis Cardinals in which Harris had two long punt returns to set up scores, the Washington Post’s Dave Brady wrote that Harris “personally launched a program to outlaw the fair catch, a play-safe maneuver that so often takes away from the fan the most exciting runs in football.”

The paper’s columnist and idolmaker, Shirley Povich, also took note of Harris’s performance. “[I]f on this night at Richmond he wasn’t making a place for himself on the Washington team,” he wrote, “the coaches were not looking.”

The coaches had indeed been looking. NFL rosters allowed for only 40 players per team in 1965, so to get the most out of his new athletic return specialist, whose first contract paid $10,000, Skins coach Bill McPeak had him learn the cornerback position during training camp. And because of injuries to the team’s veteran cornerbacks, Harris opened the season, and his pro career, in the defensive backfield rotation.

In his first real game in the NFL, Harris faced the defending champion Cleveland Browns and their all-timer running back, Jim Brown. Harris was listed by Washington as weighing 179 pounds at the time. He laughs at that stat. “I called that my ‘program’ weight,” he says. “I only weighed 146 when I got here and I didn’t gain much weight. But they didn’t want me to look like a wimp.”

Even at the inflated weight, Harris seemed underarmed to go against Brown, whose official weight of 228 pounds seems to sell him light. The week of his debut, a reporter from the Post asked Harris why he thought he’d be able to tackle Brown.

“I will have to,” Harris responded.

Brown wasn’t his usual dominant self, but visiting Cleveland won, 17-7. The following week, Harris was opposite Bob Hayes, who’d returned to football with the Dallas Cowboys after winning a gold medal in the 100 meters at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Harris remembers the strategy he employed against the World’s Fastest Man: Stay off him. “I knew that Bob Hayes couldn’t beat me in the 100 if you gave me a 10-yard start,” he says.

Then on came the Baltimore Colts and Johnny Unitas. There was no trick that worked against Johnny U. at that time. “He knew our defense better than we knew it,” says Harris. “He picked us apart.” The Colts won, 35-7.

Harris’s greatest contributions came on kicks, where he replaced a fleet of Skins, most notably Bobby Mitchell, as the go-to return specialist. Mitchell broke the color line for Washington, which hadn’t integrated its roster until 1962 and was the last NFL team to do so. Owner and founder George Preston Marshall had been told by the Kennedy Administration that if the franchise remained all-white—its fight song at the time vowed to “fight for old Dixie”—it would not be able to use D.C. Stadium, the then-new venue built on federally owned land. Harris says he was well aware of the racial situation in D.C.

“My mindset was catch the ball and run. If they kill you, okay.”

“I knew that [Marshall] didn’t want me here, and I was only here because the government made them sign players like me,” he says. “But it wasn’t real integration when I got here.”

Harris says he was assigned to be Taylor’s roommate, and that he realized no black players were rooming with white players. Taylor, a future Hall of Famer, would be his roommate throughout his entire tenure in Washington. If there were an odd number of black players on a road trip, Harris says, “Bobby Mitchell would get his own room, because he was the superstar.”

Redskins historian Michael Richman says that segregated rooming wasn’t exclusive to the Skins in 1965. “There was always a story about a quota system in the NFL,” he says, “where teams kept an even number of black players on the roster, so they could room together.” (Brian Piccolo and Gale Sayers of the Chicago Bears, the brotagonists of the blockbuster made-for-TV movie Brian’s Song, often get hailed as the NFL’s first interracial roommates. But they weren’t paired up until 1967; Washington’s Brig Owens, a black defensive back, and white tight end Jerry Smith broke the roommate color barrier the previous year.)

Harris finished second in the NFL in returns in 1965, and made the all-rookie team alongside Sayers and Hayes. He was a starter on defense by the end of the season, and retained his return duties during what would be a six-year run with Washington.

The Redskins had only one winning season during Harris’s stay, the one in which he got to play for Vince Lombardi. In 1969, the coach hailed as the NFL’s greatest bizarrely jumped from a front-office job with the Green Bay Packers, the two-time Super Bowl champs and perennial contender with whom he’d built his reputation, to lead a Washington squad that was a second-division fixture. The team’s 7-5-2 record, after 13 years at or below .500, hurt Lombardi’s career stats but only enhanced his legend.

Harris got in Lombardi’s doghouse once, when he threw a football into the stands after running back a punt for a game-winning touchdown in an October game home against the Giants. He then became only the third player ever fined by the league for that infraction, under a brand new NFL rule put in place allegedly for fan safety. (It cost him $100.) “I’m going to fine him, too,” Lombardi barked after the game. The future Hall of Fame coach told the press that he was more upset that Harris hadn’t made a fair catch on an earlier punt.

That wasn’t how Harris played the game. Whether it was throwing his smallish body in front of hulks like Jim Brown or refusing a fair catch, fearlessness was a Harris trademark. “Harris is the daring young man in the flying wedge,” Davy Brady wrote about him in the Washington Post, “disdaining the dangers of a suicidal phase of the sport.” A November 1967 Post profile noted that “the enduring wonder is how he absorbs all those lumps from kamikaze tacklers on the kicking teams.”

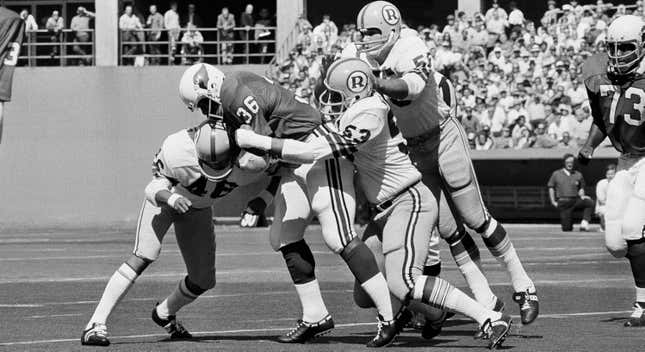

Rickie Harris (left) and teammates hit the St. Louis Cardinals’ MacArthur Lane, 1970. Photo via AP

“It’s worth the gamble to try to make some yardage,” Harris explained.

Harris now says he was afraid—of losing his job. So he never felt like protecting himself was a realistic option when a punted football was coming his way.

“My mindset was catch the ball and run. If they kill you, okay. But catch the ball and run!” he says. “I took a lot of chances. I got my ‘bell rung’ a lot. But it was a life or death thing for me. If I didn’t catch the ball and run, I wouldn’t be here long. The coaches never told me that. They didn’t have to. I knew that. So I wasn’t going to fair catch. Nobody pays you to fair catch.”

If he was a little man in a big man’s game on the field, he lived large off of it. Various Post profiles over the years drew attention to his impressive wardrobe. “His sartorial highlight in headgear was a floppy brimmed ‘Three Musketeers’ hat, one side snipped to the crown with a clutch of feathers,” noted one reporter. “His ‘mod’ civvies match his personality: a maroon grass cap, turtleneck shirt with horizontal gold stripes and lime wide-wale corduroy trousers,” another wrote. A third piece described Harris dressing in an “Edwardian” ensemble for a visit to Chicago, with an overcoat that had “lapels that could conceal violin cases.”

To what does Harris credit his fashion sense? “I was from California,” he says.

He made friends in high places, too. Harris used contacts he’d made through football to get offseason gigs with some of the country’s top power brokers. He got involved with the Office of Economic Opportunity, a federal agency that had been started by Sargent Shriver to help President Lyndon Johnson fight the War on Poverty, particularly in Indian Country. Through that he got to know Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, Shriver’s brother-in-law.

Harris stuck with OEO after Kennedy’s 1968 assassination, even though its bailiwick would soon be shifted, under Richard Nixon, to the War on Drugs. Harris got friendly with OEO director Donald Rumsfeld in 1970, when he was invited to be part of a group of pro athletes sent on a cross-country junket with something called the Mod Corps, which dispensed the administration’s anti-drug propaganda.

A portion of the Mod Corps spiel Harris gave to his impressionable audiences was printed in a July 1970 story that appeared in the Afro-American, a paper with a primarily black audience: “Yes, I have taken pep pills from a licensed physician to get me through a football game, but that’s far different from a pusher on the street.”

After he got out of football, Harris became less reluctant about getting his narcotics from a pusher on the street.

A debacle of historic proportions

The NFL was done with Rickie Harris before he was done with football.

George Allen, the father of Washington’s current team president, cut Harris when he took over as head coach before the 1971 season. New England picked him up for two years, but cut him before the 1973 season. He didn’t want to give up the game, though.

Rickie Harris, bottom, in a preseason game against the Chicago Bears, 1967. Photo via AP

“I knew I had a couple more years in me,” he says.

So the World Football League came around at just the right time. In the spring of 1974, franchises were doled out and new owners began signing a few stars in their prime. Miami Dolphins Pro Bowl running backs Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick and star receiver Paul Warfield jumped to the WFL to play alongside NFL castoffs and rookies right out of college. When the new league offered Harris a chance to get back into football, he jumped.

“I figured you still had 11 men on the field, and that field is still 53 yards wide and 100 yards long,” he says. “So it’s football! What’s the difference?”

Actually, there were some differences between the NFL and WFL versions. The new league moved the goalposts from the goal lines to the end lines, added an overtime period for tied games, eliminated preseason games and extra point kicks, and—as if Harris had been consulted in writing up the WFL rule book—banned fair catches. He thought he’d found the perfect landing spot when D.C. was awarded a franchise, initially called the Washington Capitals, and Jack Pardee, another ex-Skin, was named head coach.

Harris can’t be blamed for not knowing he was jumping into a debacle of historic proportions, but huge hints that this new team was headed for trouble popped up immediately. The original ownership group, headed by an oceanographer named Joseph Wheeler, was forced to drop the “Capitals” nickname under legal threats from Abe Pollin, who had founded an NHL team by the same name only a year earlier. Thus were the Washington Ambassadors born. Then the Ambassadors were told that Skins president Edward Bennett Williams would be exercising a clause in his team’s lease at RFK Stadium that allowed him to prevent any other football franchises from using the facility. That forced a move to Annapolis and another name change, to the Washington-Baltimore Ambassadors. No suitable stadium being available in Maryland, the operation moved to Norfolk, Va., and changed its name to the Virginia Ambassadors.

As the Tidewater move was planned, however, Wheeler confessed that the millionaire investors he’d told league officials about when he was awarded the franchise didn’t actually exist. So WFL brass turned the franchise over to Rommie Loudd, a personnel man from the New England Patriots who’d never owned a sports team before. Loudd moved the operation to Florida and christened his team the Orlando Suns, only to find out that the WFL already had a squad called the Sun based in Los Angeles. Finally Loudd chose a name that stuck—the Florida Blazers—and the football side of the organization could get to work.

Because commercial contracts had already been signed, though, training camp was held back in Virginia. And as the WFL’s 20-game regular-season schedule commenced, it became clear to the players that Loudd was every bit the deadbeat Wheeler was. Paychecks showed up late or not at all, even early in the season. A few weeks into the campaign, only the squeakiest wheels were getting paid anything.

WFL stars Larry Csonka, John Gilliam, Jim Kiick, Calvin Hill, and Paul Warfield at a press event with league president Chris Hemmeter, 1975. Photo via AP

“Rommie Loudd would look you dead in the eyes and lie,” says former Blazers quarterback Bob Davis, a New York Jets castoff. “Talk about a crook. What a creep. And we played for him! For nothing.”

Yet Pardee somehow kept the Blazers from letting the blatant financial woes take their eyes off the prize. “Pardee’s philosophy was basically, ‘We’re not getting paid, but what do we have to lose by trying to win a championship?’” recalls John Ricca, a rookie defensive lineman with the Blazers, fresh out of Duke University. “He told us to just keep at it and maybe something good will come of it. And everybody bought into it. I think it was maybe the greatest coaching job in the history of sports.”

Ricca says he got about $15,000 of the $30,000 in salary and bonuses called for by his contract. Running back Tommy Reamon, the league’s leading rusher and MVP, now says he went the whole year without getting one check.

Harris can’t recall how much money he got with the Blazers. He does remember that he never entertained any thoughts of packing it in.

“I was thinking, ‘What else am I going to do? Go home and still not get paid?’” he says. “I think everybody felt that way. Not getting paid became the glue that held us together.”

According to Blazers teammates, Harris brought his old willingness to sacrifice his body for the team with him when he jumped leagues. “I tell you, Rickie Harris was a tough football player,” recalls Davis, “I mean, he would stick his head in there, baby!”

The Blazers went 14-6* in the WFL’s regular season and won the Eastern Division. The only time the lack of cash caused discord, as Ricca recalls, came in the postseason. To make sure players got on the plane to Memphis for the semifinal game, Blazers management handed out paychecks for the first time in weeks just before leaving town. When the flight landed, Walter Rock, a Blazers offensive lineman and former Skin, found out in a phone call from his wife that the checks had been canceled by the owner while his employees were in mid-air.

“He hauled ass out of there, just quit,” says Ricca. “But everybody else stuck it out.”

The Memphis Southmen were the most moneyed team in the league, having signed Csonka, Kiick, Warfield and future Cowboys QB Danny White. But this game belonged to the squad without a payroll: The Blazers beat Memphis, 18-15.

Then came the World Bowl, and—according to legend and Harris—the flipped coin caper.

The day the money ran out

There is no known video evidence to confirm or counter Harris’s claim that he turned the coin flip into a profit center at the 1974 World Bowl. There’s apparently next to no video evidence, in fact, of the game at all.

“I’ve never seen a World Bowl tape,” says Richie Franklin, who runs a website called WFL Films and has been collecting WFL tchotchkes since the early 1980s.

The title contest was not shown on any major networks. It was, however, broadcast nationwide via TVS, a syndicated network founded by maverick broadcaster Eddie Einhorn.

Rickie Harris grabs an interception against Minnesota, 1968. Photo via AP

As a student at Northwestern in the late 1950s, Einhorn began negotiating broadcasting rights deals for college basketball games, which the national networks weren’t interested in at the time. In 1968, TVS produced the so-called “Game of the Century” between Lew Alcindor’s UCLA squad and a Houston team led by Elvin Hayes. But along with his passel of visionary attributes came an utter disdain for retaining film or videotape of any event produced by his outsider TV enterprise.

Einhorn is now a vice-president of the Chicago White Sox. If any footage of the World Bowl exists, he is unaware of it.

“We went looking a few years ago and found nothing from [the WFL],” says Scott Reifert, a spokesman for Einhorn. “He’d love to have it if it’s out there, but we’re not aware of any. Mr. Einhorn keeps waiting for something like what happened with the 1919 World Series, where somebody’s been holding the film for years and it just shows up. But as far as we know, that football game, and almost everything from TVS, is just gone.”

Mark Speck, an author and the preeminent WFL historian, says he hadn’t ever heard about the special coin being filched after it was tossed. “Harris was the Blazers’ defensive captain and would have more than likely been on the field for the coin toss,” Speck says. “Whether he took the coin and kept it I am not sure.”

There is at least one reference from back in the day to such an incident. In 1975, Sports Illustrated ran a long article chronicling the debacle-ridden reign of the upstart league, which had folded earlier that year after one-and-a-half seasons. In the piece, titled “The Day the Money Ran Out,” former New York Jets and Blazers lineman Larry Grantham tells about how he and his teammates struck back after going unpaid for a long stretch of the 1974 season.

“We were out on the field getting ready to play a game,” Grantham says. “We flipped the coin, won the toss and elected to keep the coin.”

Grantham doesn’t mention the World Bowl. But Tommy Reamon, the Blazers running back and the league MVP that season, now remembers hearing about “the coin toss issue” on the night of the World Bowl. And though Reamon, now a high school football coach in Virginia Beach, can’t recall all these years later whether the intrasquad rumors held that it was Harris who kept the tossed coin, he insists, “There’s some truth to that tale.”

The Blazers lost the title game by a point, 22-21, and folded immediately upon arriving back in Orlando. Harris latched on with the Memphis Southmen in 1975. But the team, and the whole WFL, closed up midway through the 1975 season. Harris had taken his last hit. His career was over.

A gift opens doors; it gives access to the great

Harris’s dementia was made part of the public record even before he signed on to the concussion lawsuit.

In December 2010, he was arrested in Fairfax County, Va., for driving under the influence of alcohol. It was the third DUI arrest for Harris since 2006. He was working as a security guard at the time, but he had spent the previous 25 years in and out of jobs and marriages. A gang of concerned friends had organized a reunion at a Northern Virginia church back in 1991 to tell Harris that after years of his cocaine and alcohol abuse they were just happy he was still alive. More than 200 folks, including famous former teammates, showed up.

“He lost his family. He lost his business. He disappeared on us for a couple of years,” Bobby Mitchell told the Washington Post at the gathering. “Where he’s been only he knows for sure. But he pulled himself back up, and I’m so glad to see him now.”

The spate of drunk driving arrests showed he was unable to stay straight. He faced serious jail time with the 2010 arrest. At the time, the issue of football-related brain damage—especially as relates to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE—was heating up. His attorney, John Keats, filed motions arguing that Harris’s injuries left him incompetent to stand trial. He brought in Paul B. Rosenberg of the Memory and Alzheimer’s Treatment Center at Johns Hopkins University as an expert witness. Rosenberg testified at a pre-trial hearing that Harris had gotten a “zero,” or the worst possible score, in a memory test he’d administered.

“I think that to assist with your own defense,” Rosenberg told the Washington Post in 2011, “you have to know what happened.”

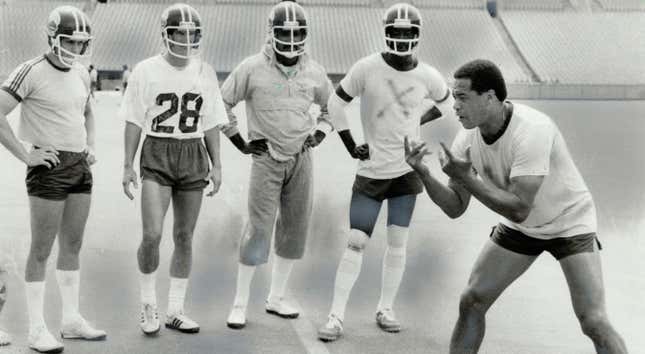

Rickie Harris works with members of the Toronto Argonauts as defensive backs coach, 1980. Photo via Toronto Star/Getty

The court, however, rejected that argument and ruled Harris was competent enough for the case to move forward. At trial, Anita Boss, a forensic psychologist, testified for the defense that Harris’s brain damage left him with almost no chance of passing field sobriety tests regardless of his blood alcohol level, which had been measured at the legal limit of .08 a few hours after his arrest.

The jury deadlocked and the judge declared a mistrial. But Fairfax County retried Harris and got a conviction the second time around. Prosecutor Laura Riddlebarger told the jury the dementia testimony was a smokescreen. “It makes the defendant a very sympathetic defendant,” Riddlebarger said during closing arguments, “but it is not an excuse for driving intoxicated.”

Harris told reporters after his conviction that NFL veterans have their own acronym to describe their condition.

“All the old players talk about ‘Can’t Remember Squat,’” he said. “We call it CRS.”

Harris’s driving privileges were taken away permanently by the court. “He would never have been able to drive again anyway, because of his condition,” says Keats. Harris also got a six-month jail sentence, the minimum sentence allowed under Virginia law for habitual DUI offenders. Because of his health, the court allowed Harris to serve his time as home detention.

He served it in his ex-wife’s townhouse in Chantilly. He still lives in the basement. He says his ex-wife and mother of his two children took him back in when he needed a place after his arrests. “Might as well spend my Social Security and pension on somebody I know,” he says. (A source within the NFLPA says that somebody who played in the NFL between 1965 and 1972 would qualify for a pension of $2,000 a month, beginning at age 55.)

“All the old players talk about ‘Can’t Remember Squat.’ We call it CRS.”

After his convictions, Harris signed on to the concussion lawsuit. He says he’s depended on former teammate and ex-NFLPA staff lawyer Brig Owens to navigate him through the case. Owens, who has stood by Harris again and again during his most troubling off-the-field episodes through the years, declined to discuss his longtime friend’s situation.

The symptoms that have plagued Harris, including chronic substance abuse, long stretches of waywardness, and acute memory loss, are routinely found among the plaintiffs. Jason Luckasevic, the Pittsburgh attorney who began working with former NFL players in 2006 to put together the original concussion lawsuit, says he’s still stunned by the impact of the game on his clients’ brains.

“The loss of short-term recall is common,” he says. “It’s shocking when you experience that for the first time. You don’t keep dialing somebody up and five minutes later have the same conversation and 20 minutes later have the same conversation and then the next day call up and start it all over again. That’s not normal. It’s part of an overall loss of cognitive ability.”

To be eligible to get a piece of the $1 billion pie outlined in the settlement, NFL players must be diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease), Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, early or moderate dementia, or CTE, the last of which can only be diagnosed after death. Luckasevic says that three of his clients (Justin Strzelczyk, Terry Long, and Andre Waters) were found to be CTE sufferers after committing suicide. The length of a player’s career will also factor into how much money they can receive. There has been no ruling yet on whether playing in a professional football league other than the NFL will impact the size of an award. The maximum payout for an individual plaintiff is $5 million.

Harris, who is represented in the concussion suit by the Minneapolis firm of Zimmerman Reed, got notice on Friday alerting him to the settlement. He has no idea how much the deal will bring him or when any share might come. He knows he’s damaged goods, and that his playing days left him in that shape. But he got something out of the bargain already.

“The Bible says your gift will make a way for you in life,” he says. “My gift I guess was I was a heck of an athlete. I got problems, but I can get around. And, at the same time, I got out of South Central and worked for the Kennedys and Nixon and Donald Rumsfeld. I got on television. Like I tell my grandkids, ‘The only thing grandpa can do is some more.’ I wouldn’t trade the life I lived in any way.”

I tell Harris that his outlook is enviable. Within seconds he says, “The Bible says your gift ...”

To end our conversation, I thank Harris for letting me impose on his time and hear all the old football tales from the guy who lived them. He’ll have none of that.

“Thank you for remembering me,” he says. “It’s nice to be remembered.”

Contact the writer at [email protected]. Image by Jim Cooke, photo by Getty.