I’m standing in Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn, New York, a place Ali and Jake LaMotta trained in decades ago, and Johnny Rodz is giving me shit because I told him I like The Wrestler.

“Is that what you really think wrestling is?” I’m repeatedly asked in a condescending tone.

I tell him I like the work of the film’s director, Darren Aronofsky, and that it seemed, at least to an outsider like me, to be a fairly accurate depiction of what life as a pro wrestler is really like. Its scenes certainly felt more authentic than anything I’d seen in Hoosiers or Any Given Sunday. Rodz agrees with these points, but he didn’t like the scene in which Mickey Rourke’s character, Randy the Ram, is shown taking steroids. “I don’t give a fuck about Aronofsky,” is how he concludes a 40-minute conversation about the movie.

If there’s anyone who should know what wrestling is really like, it’s Johnny Rodz. He’s a WWE Hall of Famer who has been in the ring with the likes of Andre the Giant and Roddy Piper, and was, to hear him tell it, instrumental in their rise to superstardom. Since retiring from the sport, he’s become a well-respected trainer whose past students include S.D. Jones, Taz, Tommy Dreamer, Matt Striker, and the Dudley Boyz.

That’s why I’m at Gleason’s, the place where Rodz runs his wrestling school. I want to learn what a wannabe WWE star has to go through before he can even think about oiling up and strutting into the ring in front of thousands of rabid fans. I want to know where wrestlers come from, and I want to know who fine-tunes their skills. Other sports have AAU teams, high school powerhouses, and big-time college programs acting as a pipeline, but wrestling has people like Johnny Rodz, a 74-year-old man running a wrestling school out of a tiny office in a dingy gym.

“If you call this is a school one more time, I’m gonna fucking kick you outta this place,” Rodz growls at me. I quickly learn that Rodz hates it when people call his program a school. While on the phone with a potential customer who wants to know how much it costs to attend Rodz’s school, the old wrestler barks, “Going to a wrestling school is a silly thing to do if you want to do professional wrestling.”

According to Rodz, wrestling schools mistakenly offer students a fixed end date. $1,500 might get you six months, and only six months, of training. Or they’ll charge several hundred bucks a month, excluding gym fees. Rodz insists he runs a club or dojo. Because for $3,000, he gives his students a lifetime membership. Wrestling schools are “stealing money from people who are stupid,” as Rodz puts it. But wrestling clubs give their members the time necessary, perhaps years, to actually learn enough about wrestling to become professional.

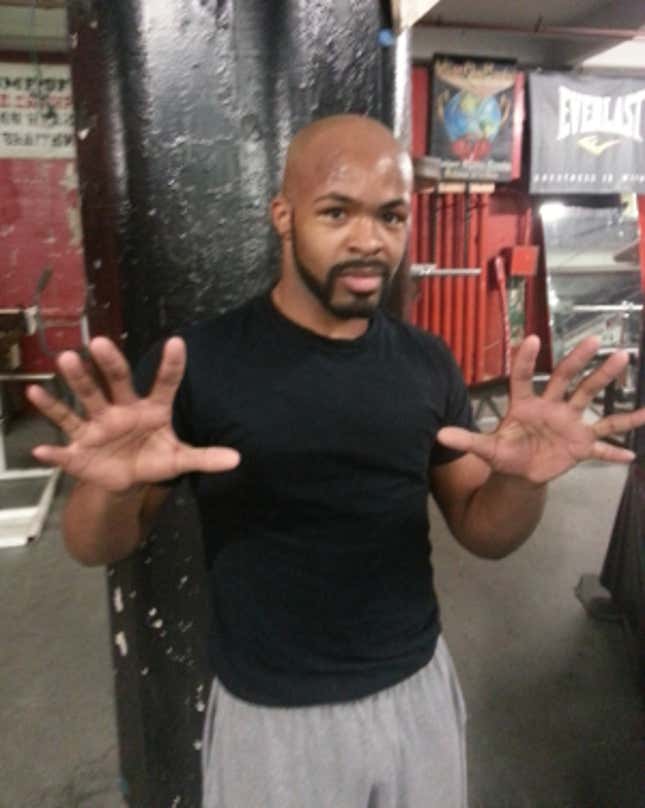

Rodz spends nine hours a day, four days a week, training his students. He gives them hands-on, in-ring instruction, and is assisted by other trainers and friends from the wrestling business. Some of them, like former student Mark Davalos, now 50, volunteer their time. “I’m fucking nobody,” Davalos says of himself. “But I know what I know. I know who I’ve taught. And that’s good enough for me.”

Davalos typically makes the roughly three hour trip from Lansford, Penn., three days a week because he believes it’s the older members of the dojo’s duty to come back and help educate the younger wrestlers. He loves being around the ring. “Inside those four poles, you can do things you can do nowhere else in the world,” Davalos tells the trainees. “I’m not here to hurt you. I’m here to fuck you up. Mentally, physically, emotionally, so you can learn to live without fear. Because you are going to need that if you want to become a professional wrestler.”

Davalos is not one to sugarcoat the wrestling business. “Every promoter is a pimp. And wrestlers ain’t nothing but sports hoes,” he tells me. But he sincerely believes Rodz’s program is a great place to learn the trade. “If every promoter is a pimp, then Johnny Rodz is a madam. Because he knows what it takes to do the job.”

As Rodz likes to say, he was “born in the hills and raised in the concrete jungle.” He didn’t start attending school in his native Puerto Rico until he was 11 years old, because the school was more than five, scratch that, seven miles away from home. The way to school was hilly, and the valleys would fill up with water when it rained. Because Rodz’s parents worked, he had to make the trip on his own. It wasn’t until he was 11 that he was tall enough to trudge through the flooded areas without fear of drowning. By the next year, Rodz’s family moved to New York, and he was bumped from first to fourth grade.

“They put a kid in fourth grade that didn’t speak English. I was 12 years old. How the fuck can you go to school when you are 12 years old and you don’t know what the fucking ABCs are all about? You see it. But you don’t understand it. It’s hard man. It’s hard,” Rodz says.

As a teenager, Rodz attended a vocational school to study auto repair. Given his poor academic standing, the school found it easy to toss him out when he got into a fight with his classmate at age 18.

So he started saving up, little by little, to pay for training to become a pro wrestler, because that was an occupation he could pursue without education. He “shined fucking shoes,” delivered telegrams, mopped floors, and saved every dime. In his desk, there’s a line of nickels he got as childhood gifts; he saved them in case he ever needed money for training. He still keeps them in a Styrofoam case covered in plastic to show his students what real discipline looks like when they whine about their situation.

Rodz keeps a thinly trimmed black mustache, with some grey sprinkled in, which spreads out above his top lip. His hair is gone, and you can see sandpaper-colored speckles on his tan dome as it reflects his office’s incandescent light. His neck is draped in jewelry. Some of it, like the Jesus Christ medallion, are a throwback to his native land where “everybody was religious.” The 18-carat diamond pinky ring comes from growing up in Little Italy. He appears wider and shorter than his wrestling days, though it’s tough to size him up in the baggy wool sweaters he wears. When he demonstrates striking techniques to his students, I’m fairly certain he’d still whip my ass in 30 seconds.

When I tell Rodz that his description of his upbringing paints a pretty grim picture, he backs away from melodrama but maintains his appeal to grandiosity. “Don’t feel guilty,” he says. “I’m a worker. I’m the best worker you are dealing with. You don’t know what a worker is. I’m a worker. I’m a performer. I’m not an actor. I’m a Real McCoy,” he says.

He’s also a WWE Hall of Famer despite never holding a title or being a fan favorite. You can try to slur him as a jobber, but that misunderstands how integral good jobbers are to professional wrestling. Rodz was one of the best, and it’s why he shared a Hall of Fame induction class with Jimmy Snuka, Killer Kowalski, and Vincent J. McMahon. The veteran members and trainers in Rodz’s dojo tell me that Rodz was McMahon’s—Vince J., the father of today’s WWE CEO “Mr. McMahon”—number one trainer, a “tuning fork” the company used to see if players were ready to play. They tell me that he would “tame” new talent and let McMahon know if they were worth a shit. They say McMahon would get Rodz’s input on bookings, and would ask him if someone should turn heel. If not for Rodz, they claim, the world wouldn’t know who Roddy Piper is.

The glory days are long gone, though, and now Rodz spends a lot of his time dealing with people he calls nincompoops. Prospective students who call and ask if he can rework his schedule so as to better accommodate their training? Nincompoops. Vince K. McMahon? Nincompoop for making it all about TV. Darren Aronofsky? Nincompoop for making that dumb movie. Paul Heyman? Nincompoop for running ECW into bankruptcy. Me? Surely a nincompoop for not fervently following wrestling. Many of Rodz’s replies to my questions are punctuated with “but you’re not a wrestling fan,” even after I’m able to recognize the face of Al fucking Snow on a signed photograph hanging in his office.

He means nothing personal. Rodz just takes wrestling even more seriously than J.J. Watt takes football. He could be spending his retirement in relaxation, but instead he treks from Staten Island to Brooklyn four days a week and crams himself into his tiny office. He says operating a wrestling club is impossible to profit from if you truly want to provide adequate training time. He says he’s “broke” but doesn’t get into it any further. He says the “wrestling game can be a real bitch” and acknowledges the difficult odds stacked against someone looking to climb the professional ranks.

Dave Meltzer, a renowned pro wrestling and MMA reporter and editor of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, tells me that at most there are 200 people making a living wrestling. But there are thousands who want to do it. One way to boost the odds is by going to a school run by a well-respected wrestler such as Rodz. If the instructor has a good reputation, promoters will take a harder look during tryouts. But many people who sign up don’t realize how demanding the training can be.

“I know top fighters who have done pro wrestling. And I don’t know one of them who doesn’t say pro wrestling is harder … People think wrestling is easy. And it’s just like this fun thing. But you got to have a real passion for it and really want it. Because if you don’t want it, you’ll never last. It’s just so physically hard,” Meltzer tells me.

Charles Johnson Corchado, 25, comes all the way from West Hempstead. He joined the club at 19 to get out of the house and find an activity to help combat his depression. His ring name has changed from Charles Johnson to The Hand Johnson to 12 Fingers Johnson, but he finally settled on 12 Fingers Tarantula. In case you were wondering, yes, he does have 12 fingers. He’s cool with playing up the abnormality. “It’s perfect. It’s there. I don’t need to do anything for it. It’s just there.”

Ann Khozine, 17, can’t even wrestle in the club’s live events until she turns 18. Given the $70 monthly dues for Gleason’s and the $3,000 membership fee she owes Rodz, she’ll likely be making an investment greater than four grand by the time she performs in a show. She works multiple jobs in retail and is an instructor at a gymnastics camp. She also gets financial help from her mom, who agreed to pitch in as long as Khozine stays out of trouble.

“I started early because I didn’t want to wait,” says Khozine. “In my mind, I get two years of practice. And by the time I start doing it, I’ll be better than if I just started … My parents don’t want me to become a wrestler, because they think it’s stupid. But they know I wouldn’t stop bothering them until they signed me up. My mom knows this is the only thing I’ve ever really wanted in life. And I’ve been bitching about it since I was like five.”

Khozine rocks curly blue hair, lip piercings, a throwback Undertaker shirt, and forest-green wrestling shoes straight out of Vision Quest. Though she’s significantly smaller than the other wrestlers, and has only been in the club for a few months, her gymnastics background leads a few trainers to remark “she’s a natural.” While the maneuvers and slams often look raw and awkward at this stage in development, she’s already convincingly selling submission holds, rolls and pin attempts, and appears to have the necessary agility to jump off the ropes. At one point she puts her opponent in a figure-four leglock and maintains the hold, rolling him back and forth across the mat until he grabs the ropes to force a break.

But this doesn’t come so quickly for everyone. One guy has trouble just rolling across the ring. He’s repeatedly told “It’s all about momentum” and to bring his hips in so he can get back up easier. He’s forced to practice his drills holding onto the ropes to gain better balance. Another likes to “jump just to jump” and Rodz warns him that he’ll kill himself on the turnbuckle if he doesn’t do it more safely. Many accidentally skip techniques that will save their bodies. They scrunch up during takedowns, instead of gracefully anticipating it and working it into the next series of moves. “You can take a chance with your vertebrae. Or you can take a roll, and come back,” a trainer yells.

The bodily toll wrestling takes is infamous, but taking a beating is only part of the game, as Meltzer tells me. It’s making sense of everything and quickly thinking on your feet, like these newbies are trying to do, that often gets overlooked. “And do it in a way that doesn’t look like you are remembering,” Meltzer said. “Where it looks spontaneous. And to get up when you’re hurt, because that’s all part of it.”

These are the little things that the average fan probably never notices, but are foundational to any successful wrestling career. An upstart wrestler can have all the strength and charisma in the world, but if they can’t safely execute a roll or learn how to play off their opponent’s movements on the fly, they aren’t going to make it. It’s within these imperceptible margins that Rodz’s mastery of the sport really shines.

You can see Rodz’s technical skills in a 1985 match against Bob Backlund, shown in the video below:

At the 2:22 mark, Rodz seamlessly rolls with Backlund’s reversal, and for a moment it appears as if the two are engaged in non-scripted grappling. Three minutes in, Rodz gracefully takes a bump as he summersaults out of Backlund’s slam. Then at the 4:22 mark, Rodz slams himself into the mat, giving the appearance that the fan-favorite Backlund overwhelmed Rodz with brute strength. Suplexes and flying elbows off the top turnbuckle are great, but every wrestling match is greatly improved by the presence of a technician who knows how to sell the spectacle of the little moments.

It’s this mastery that led legendary wrestling play-by-play man Jim Ross to say things like, “Bell to bell, Johnny Rodz is as good as anybody that this company has ever paid a paycheck to.” It’s what makes former wrestler and current talent scout Gerald Brisco call Rodz a “technician” and a “mechanic” who “could have a match with a broomstick.” It’s why Rodz gets a little fed up when people interested in joining his club call him up and ask if he “knows anybody in WWE.”

“Well let me ask you, do you know who you are talking to?” He says to one such person. “The first name on the website is The Unpredictable Johnny Rodz. He’s the guy who owns the World of Unpredictable Wrestling. And he’s a WWE Hall of Famer. If you don’t know The Unpredictable Johnny Rodz, then you don’t love wrestling.”

Two high school kids from East New York show up unannounced at Rodz’s dojo. Prospective members are supposed to call first and arrange an appointment, but Rodz meets with them anyway, and asks why they want to train here.

“I want to be trained by you,” the older one pipes up. “I want to learn things that I can use when I’m with my friends having fun.”

“You think wrestling is fun?” Rodz asks as his voice rises and eyes narrow.

“Eh … I didn’t mean fun. I meant, eh …’

Rodz interrupts the kid’s stumbling speech. He smiles, and says he knows what he means. He then asks them how they are going to pay $3,000 for a membership?

“I’ll do whatever it takes. I’ll save a little every time I get paid. I’ll use my next paycheck.”

When Rodz brings up the three grand again, the kid realizes it’ll take a damn long time working after school earning minimum wage at a fast food joint to build up $3,000 in disposable income. It’s clear he was expecting something cheaper. At this point, the kid, a junior, and his brother, a freshman, are just eating up Rodz’s day when he could be aligning his next show. And it’s clear Rodz would rather be doing that than haggling with someone who perceives wrestling training to be cheap and fun.

Instead of booting them out, though, Rodz tells them they can hang around and chat with the wrestlers here. He says they should finish school, then come talk to him once they’re more settled and able to start realistically paying for a membership.

People showing up unexpectedly in Rodz’s office doesn’t happen every day, but it’s not exactly uncommon either. Gleason’s is a tourist stop. Sometimes people Rodz doesn’t know nor will ever see again come in, ask lots of questions, take loads of photos, and interrupt his work.

One day a group of German 20-somethings check in. Given their age and how excited they are to learn Rodz trained the Dudley Boyz, they fit the mold of Attitude Era fans. They ask if he wrestled Kurt Angle or Chris Jericho. Rodz just smiles and says, “No.”

He doesn’t tell them he earned $500 a night grappling at the old Madison Square Garden a decade before Jericho was even born, or that he took on legends much greater than Angle, like Andre the Giant and Bob Backlund.

Rodz tells me, “I made Roddy Piper be the champion. I help all these fucking guys be champions.” But the only thing he tells the tourists is to have a nice time in New York.

He pushes down his resentment when strangers accidentally waste his day, only to later grouse about how far behind he is on his work because of those unproductive meetings, and how he needs to make headway before he plugs the meter. While going on about these setbacks, or whatever else is bothering him that day, he’s liable to stop mid-sentence and go on a completely unrelated tangent. (“Are the Indians Mongonlians? Before we came here, we didn’t know what to call the Indians here. What did the Indians call it before we started calling it America? See I want to help you with my story, but you are talking to me, and you ask how I started.”)

Getting straight answers from Rodz sometimes takes a lot of endurance. But if you hold on just long enough, and get through a berating over film preferences or the mistake of calling his program a school, he’ll open up and sincerely share what he’s experienced and what he knows. He might even invite you to hang out and watch some of his old wrestling matches on DVD. He does this with me one day at Gleason’s, and I see him smile for the first time all day while taking in the grainy footage.

“You hear the people?” Rodz asks when the boos rain in on screen after he draws some heat. “They are waiting for him to kill me. See that’s what the whole thing is all about. Make the people go crazy … You have to be a tough guy to take all these bumps. That’s why I did that to the boxer, because he had no respect for me. I could kill him in two minutes. I could kill him in 30 seconds, never mind two minutes. But for the Real McCoys, that’s the difference. That’s real. I don’t want to hurt the guy to make the people go crazy. But if you fight me on the street, we don’t need to have a crowd.”

The boxer he mentions is a guy who, about 20 years ago, was foolish enough to suggest that wrestling was “phony” to Rodz’s face. The boxer took a jab at the old man, and Rodz quickly blocked the punch with his forearm, which gave the boxer a hyperetended elbow.

It’s 9:00 p.m. and Gleason’s is shutting down for the night. As the wrestlers migrate from the ring to Rodz’s office, he tells them about the time he had put over “some dickwad thief” and how being a professional is “being able to deal with assholes like that.”

They all gather around Rodz’s desk to tell him goodbye. As they’re putting on their jackets, Rodz tells them how his biggest wish is to see them all get tryouts and pass. “And when you get a tryout and they ask where you come from, that’s when you know they’re probably interested … But it’s a bitch, because you never know when that’s gonna come.”

Earlier in that very same office, a student came in wincing and pointing at a quarter-sized patch of skin missing from his elbow. He told Rodz the mat gave him rug burn. Rodz told him to quit putting his elbow down when he falls and rolls. Instead, push the arm out, and do a sweeping motion to take the bump more smoothly and spread the pressure across more surface area. There was Johnny Rodz, a master of his craft, imparting a small but important piece of knowledge onto one of his students.

Rodz then politely told the student to put ointment on the wound, and to cover it with tape. After the guy left, Rodz turned to me and said, “That’s what we call pussy. Ain’t no fucking way he’s gonna be a professional wrestler. You have to go through hell to be a pro wrestler.”

Illustration by Sam Woolley

Ross Benes has written for the Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Quartz, and Slate. His upcoming book about indirect relationships between sex, economics, politics, and religion will be published by Sourcebooks next spring. Follow him on Twitter: @RossBenes.