Rory Best should have stayed in Carton House with the rest of the Irish national rugby team. Instead, the captain and starting hooker sat in Belfast’s Laganside Crown Court alongside his teammate Iain Henderson, watching the trial of two other teammates for the alleged rape of a 19-year-old woman in June 2016. Paddy Jackson, Ireland’s trusted and surefooted back-up at fly half, and Stuart Olding, one of Ireland’s best prospects at the center position, stood accused of raping the woman, unnamed for legal reasons, in Jackson’s house.

The appearances of Best and Henderson were as important as a big hit or a turnover in the early stages of a rugby match; a message was being sent to the accuser. In texts to a friend in the immediate aftermath of the incident, the woman said she was afraid to pursue the rape claim against Jackson and Olding to avoid “going up against Ulster Rugby” (the club all four men played for). Indeed, she wasn’t just taking on Jackson, Olding and the other two defendants—Blane McIlroy, who also has a handful of Ulster appearances to his name, was charged with exposure, while Rory Harrison was charged with perverting the course of justice and withholding information—but also the whole organism of Ulster Rugby, led Best, who sat watching in the gallery.

Best is one of just five players to have appeared more than 100 times for the Irish national team. A soft and somewhat reluctant speaker, he is the kind of leader who plays on with a broken arm. In leaving the Irish team’s training base in Carton House, a luxurious Georgian estate in Maynooth, County Kildare, Best, in choosing to attend the trial, made the first serious misstep of his career. Three days out from the beginning of the Six Nations, rugby’s European championship, the on-field spearhead of Irish rugby was in the courtroom’s public gallery, under the direction of the defendants’ lawyers, nominally to lend support to friends and colleagues, but more likely to intimidate a woman who had the temerity to take on the favored sport of Ulster’s middle class. His appearance in court and subsequent refusal to discuss it caused a huge backlash. Some fans called for Best to be stripped of the captaincy and the hashtag #NotMyCaptain became the first of three hashtags to define a case that would dominate Irish social media for its duration.

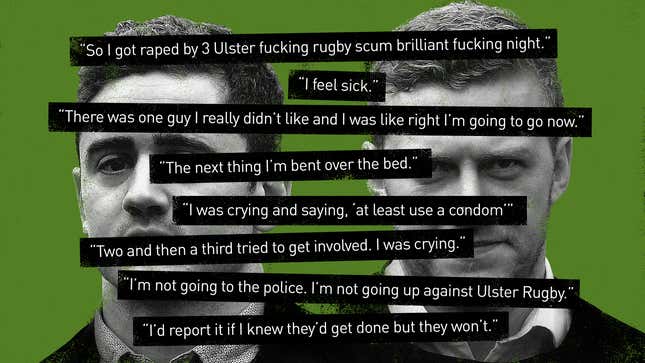

The story of how two of Ireland’s best young rugby players were accused of rape can be told through the texts of the parties involved, starting in the VIP section of Ollie’s Club in the Merchant Hotel in Belfast. The four defendants left there in two taxis headed for Jackson’s house at 2:30 a.m. on June 28, 2016, accompanied by four women, including the accuser. At 5 a.m., the woman left Jackson’s house in another taxi with Harrison; the driver would later testify that she was “crying/sobbing throughout the journey.” What happened in between, according to text messages retrieved from the woman’s phone, was that she “went back to their house … There was one guy I really didn’t like and I was like right I’m going to go now. Went to get my shoes but my clutch was upstairs… and Paddy Jackson came up behind me. He’d already tried it on earlier and I firmly told him where to go. The next thing I’m bent over the bed. I have bruising on my inner thighs. I feel like I’ve got bruising. They were so rough I’ve got my period a week early.”

Asked if there was more than one attacker, she replied: “Two [who she identified as Jackson and Olding] and then a third [identified as McIlroy] tried to get involved.” A text from Harrison, who she referred to as a “really nice guy,” asked if she was “feeling better” at noon on June 28; the accuser responded “what happened was not consensual which is why I was so upset.” In WhatsApp group chats the next day, Olding, Jackson and McIlroy referred to themselves as “legends” and “top shaggers” who were doing “a bit of spit roasting” like “a merry go round at the carnival” on a girl who “was very loose.”

After spending June 28 at Brook Clinic, a sexual health center in Belfast, and the Rowan Sexual Assault Referral Centre in Antrim, the woman called the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) on the morning of June 29. The PSNI contacted Ulster Rugby to arrange for Jackson and Olding to come to Musgrave Police Station on June 30, where they were arrested. McIlroy was arrested later the same day, while Harrison provided a witness statement. The next day, another witness, Dara Florence, told police that what she saw when she entered Jackson’s bedroom she didn’t believe to be rape.

Jackson and Olding were released, then re-interviewed in October 2016, when Harrison was interviewed by police as a suspect for the first time. In his interview, Harrison told police that his phone had been wiped and that he had lost all messages, photos and data on it. Retrieved message logs were shown to the court, showing Harrison’s conversation with the woman, as well as a conversation with McIlroy after the arrest of Jackson and Olding where McIlroy said it was “a good night, I loved it,” and asked where the woman lived, what her name was and where she went to school. All the while, the pair continued to play rugby.

As a kicker and fly half, Jackson was Ulster’s principal score getter, scoring 162 points across 18 club appearances in the 2016-17 season. As Ireland’s backup fly half—the understudy to the legendary Jonathan Sexton—Jackson appeared in nine games while under investigation for rape and scored 89 points. Olding, a versatile player mainly used as a center, but sometimes at fullback, played in 14 games for Ulster, scoring 16 points. He was not selected for Ireland during the season, but his call-ups make it clear that he would have been had he played well enough.

In July 2017, with the rugby season over, the Public Prosecutions Office decided to press forward with the case. Jackson was charged with rape and sexual assault, Olding with two counts of rape. Ulster Rugby and the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) immediately released a statement saying that Jackson and Olding would be “relieved of their duties and obligations” in order to “allow the players time to address this matter fully.”

Before the trial began on January 29, all defendants pleaded not guilty to their respective charges (one charge of rape against Olding was dropped). On January 31, Rory Best and Iain Henderson appeared at Laganside Crown Court; three days later, Best captained Ireland and started at hooker, with Henderson at lock, as they eked out a 15-13 win over France to start their Six Nations campaign. In between this and a Best try in a 56-19 victory over perennial Six Nations whipping boys Italy the following week, every item of clothing worn by the woman on the night in question, her bloodied underwear included, was displayed to the court for all present to see.

Three days after the Italy game, Paddy Jackson denied having any type of intercourse with the woman, consensual or otherwise. Ten days later, Jackson claimed that the woman had mistaken his fingers for his penis, as he had been behind her, and then said that he “presume[d] she wanted it to happen.”

Ireland, without the injured Henderson, beat Wales the next day. Henderson returned as a substitute as Ireland wrapped up the Six Nations championship with one game to go after a victory over Scotland on March 10. In court the next week, Jackson’s barrister, Brendan Kelly QC, unloaded on the accuser, telling her that “drunken consent is still consent” and accused her of taking the morning-after pill to look like a “classic rape victim.”

On St. Patrick’s Day, Ireland beat England in Twickenham Stadium to confirm themselves as the best team in European rugby. In doing so they completed a Grand Slam—an undefeated Six Nations campaign—and also won the Triple Crown, a mini-tournament between Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales. It was a poetic victory, beating the old colonial master at their own game, in their backyard, on Patrick’s Day, but it was coloured for some by the sight of Best, a man who had so clearly tried to sway a rape trial less than two months before, receiving Ireland’s trophies.

The following week, apparently not wishing to be outdone by Brendan Kelly, Stuart Olding’s barrister, Frank O’Donoghue QC, asked the woman why she didn’t “scream the house down. A lot of very middle-class girls were downstairs,” he went on. “They were not going to tolerate a rape or anything like that.” His implication—that working-class people would tolerate a rape and that a rape taking place among middle-class people would be unthinkable—was clear to everyone.

The Irish rugby team represents a unified Ireland, the entire island rather than either of the partitioned states of the Republic of Ireland or Northern Ireland. Ireland’s four professional rugby clubs represent Ireland’s four provinces: Leinster, Munster, Ulster and Connacht. Six of the nine counties that make up Ulster also make up the state of Northern Ireland. Rugby is a middle class sport anywhere it’s played—predominantly former British colonies, alongside France, Italy and Argentina—and rugby players are afforded a god-like status anywhere in Ireland because it is the team sport the country has proven to be most consistently good at. In Ulster, rugby sits at an uncomfortable intersection of class and sectarianism. The accuser’s trepidation about taking on Ulster Rugby was validated when her underwear was exhibited to the court and she was portrayed as a silly little girl who regretted a consensual encounter. This anxiety was rooted in the knowledge that the majority of Ulster Rugby’s fanbase is the kind of people the state of Northern Ireland was created to protect: white, middle-class, Protestant males like the four defendants.

In the Republic of Ireland, elite rugby players are typically alumni of elite private schools in south Dublin or Cork. In the north, they are usually products of elite grammar schools, which are not fee-paying, but are selective. Of the 36 players selected for the Irish squad against England, only nine did not attend a private or grammar school, and three of those are naturalized citizens not born or raised in Ireland. Jackson and McIlroy attended Methodist College Belfast, the record winner of the Ulster Schools Cup, where they won two cups. Olding attended the equally prestigious Belfast Royal Academy, Belfast’s oldest school. That the barristers of the accused would go all out was no surprise; the accuser spent eight days in total on the stand, with none of the defendants doing any more than a day in the box. The slut-shaming of the defendants’ WhatsApp texts was echoed in their legal teams’ lines of questioning, but it worked for them in the end. On March 28, all four defendants were found not guilty on all charges.

Through his solicitor Paul Dougan, Olding apologized for “the hurt that was caused to the accuser.” Jackson’s solicitor, Joe McVeigh, thanked the jury for returning a unanimous “common-sense verdict” and claimed that it was Jackson’s “status as a famous sportsman that drove the decision to prosecute in the first place.” The IRFU immediately announced that Olding and Jackson would remain unavailable for selection while it conducted its own internal review into the incident. The hashtag #IBelieveHer became Ireland’s most tweeted topic and rallies were held in Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Galway and Belfast in solidarity with the accuser.

But rather than taking the opportunity to lay low for a while, Jackson decided that it was time to create a fresh controversy. In the immediate aftermath of the #IBelieveHer hashtag, Jackson began defamation proceedings against the Irish senator Aodhán Ó Riordáin, who had tweeted (and eventually deleted and later, apologized for) his disapproval of the verdict. Jackson’s lawyer then threatened anyone using the hashtag with similar action. All this did was create the third and final definitive hashtag of the entire ordeal; #SueMePaddy quickly became the new number-one trending topic.

When Jackson eventually apologized for the woman’s torment last week, saying he was “ashamed” and that the backlash was justified, any sincerity was undercut by the earlier legal threats and gave the impression of a man who knew that the legal battle had been won, but the public one lost.

More legal developments came when it emerged that a juror was under investigation for contempt of court after discussing the case in an online comments section, and two people were questioned by police after naming the accuser online. Media outlets are also challenging Judge Patricia Smyth’s ruling that a ban on reporting court happenings that occurred when the jury was not present would be extended past the end of the trial; usual practice is that the restrictions are lifted once a verdict has been delivered, as it is no longer possible to influence the jurors.

A story with no end in sight took yet another turn when the Ireland and Ulster winger Craig Gilroy, who played on the same Methodist College Belfast team as Jackson and McIlroy, was suspended by the IRFU and Ulster after it emerged that he was the participant in the group chat that had asked “any sluts get fucked?” Gilroy will certainly be brought back into the fold at some point, but the attention is now turning to whether or not Jackson and/or Olding ever will. A crowdfunded ad in the Belfast Telegraph, Belfast’s biggest daily newspaper, asked both Ulster and the IRFU to sever ties with the players. Thousands have signed competing petitions calling on the IRFU to never let the pair play again, or, alternately, to be reinstated immediately.

It should be cut and dry for the IRFU. The Grand Slam victory, and the emergence of Leinster’s prodigious fly half Joey Carbery as back up to Johnny Sexton and Garry Ringrose and the naturalized New Zealand native Bundee Aki in the center, have rendered Jackson and Olding unneeded and unworthy of the backlash selecting them would rightfully cause. Ulster are not so lucky; they currently have the seventh-best record in the PRO14, a league made up of 14 clubs from Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Italy, and South Africa. Seventh is not good enough for the first Irish club to ever win the European Rugby Champions Cup, and as a team they have lacked the control a fly half like Jackson can supply.

But this isn’t about rugby any more, and after fielding two players under investigation for rape for an entire season, it’s unlikely that anybody empathizes with Ulster for their poor results. “We demand that neither of these men represents Ulster or Ireland now or at any point in the future,” the ad in the in the BelTel reads, accusing Jackson and Olding of falling “far beneath the standards” Ulster Rugby and the IRFU demand of their players, the most high-profile pros in Ireland. What happens next will determine if those standards only concern on-field talent, or if character matters too.

Odrán Waldron is a freelance writer from Ireland, whose work has appeared on VICE, New Socialist, An Poc and Pop Matters, among others. You can follow him on Twitter @odranwaldo and follow his writing at www.clippings.me/odranwaldron.