Howie Rose was never one to use a canned line, but this called for something special, something that would convey the size of the moment. On May 27, 1994, as the Rangers clung to a 1-0 lead over the Devils late in the third period of Game 7 of the Eastern Conference finals, words began to form in the radio play-by-play announcer's head.

Now there's one more hill to climb.

"That's how I was going to end the game," he says now. He had it all planned out, too. He would deliver the line, then immediately defer to the crowd's roar, "to punctuate the euphoria that was evident coming through the radio."

If they could hang on for a few more seconds, the Rangers would have a shot at winning their first Stanley Cup in 54 years. Rose knew the stakes as well as anyone. He'd been a fan of the team since his childhood in Queens, a former season ticket holder, in fact—Section 429, Row G, Seat 11, near the Eighth Avenue subway line on the 33rd Street side of Madison Square Garden.

Less than a minute before the final horn, Rose braced himself. Then, with 7.7 seconds to go, Devils forward Valeri Zelepukin managed to jam a shot under Rangers goaltender Mike Richter's left pad. Agonizingly, the puck slid into the net. Rose felt like swearing, but instead simply stated the obvious: "They score on the rebound! Richter is furious!"

And so was Rose. The Devils had tied it. "There was incredulous anger in my voice," he recalls. The goal sent the game to overtime and caused hundreds of thousands of existential crises across WFAN's coverage area.

He didn't know it right away, but for Rose, the goal was a blessing. It forced him back onto his instincts, back where broadcasters' careers are made.

In early 1994, Stéphane Matteau suffered an existential crisis of his own. On March 21, the Blackhawks traded him and Brian Noonan to New York for future All-Star Tony Amonte and the rights to prospect Matt Oates. Matteau had played for Rangers coach Mike Keenan in Chicago. Still, the move shocked the 24-year-old left wing. He'd been sent to the best team in the league. What did it want with him? "Oh my God, I'm just going to be a spare player," he later admitted thinking. "I'll be on the fifth line, just waiting in case someone gets hurt."

But to his surprise, Matteau quickly became a steady contributor. In his first game as a Ranger, he scored late to salvage a tie in Calgary, his first NHL stop. In a dozen regular-season games with New York, he finished with four goals and three assists. The Presidents' Trophy-winning Rangers plowed through the Islanders and the Capitals in the first two rounds of the playoffs before the New Jersey series, which quickly turned brutal. Two of the first three contests went to double overtime, including Game 3, which Matteau won for the Rangers by zipping a backhand shot past Devils goalie Martin Brodeur. The winger called the goal lucky. "I just put my stick down," Matteau told the New York Times, "and I saw the puck at my feet."

After the Devils improbably took a 3-2 series lead, New York captain Mark Messier—to the squees of the Post and the Daily News—guaranteed his team would win Game 6. He backed up his prediction by scoring a hat trick, leading the visiting Rangers to a 4-2 victory. Two nights later, at the Garden, the teams met in Game 7.

Ask New Yorkers about that time and they'll get that look in their eyes, the one that tells you you're about to spend the next 15 minutes listening to someone ramble on about Paul O'Neill or John Starks. But 1994 was a special year for New York sports fans. Not only did the Rangers finally look like a championship contender, the Knicks were rolling toward their first NBA finals appearance in 21 years, and the Devils, Islanders, and Nets all made the playoffs, too. Seemingly every night for months, a local team played an important game. "The number of divorces in New York must've multiplied by a significant number that spring," says Eric Spitz, then WFAN's assistant program director.

To Rose, Devils-Rangers felt familiar. Back in 1971, New York and Chicago played a seven-game marathon in the semifinals. Down 3-2 in the series, the Rangers managed to win the sixth game, 3-2, when Pete Stemkowski scored in triple overtime. But naturally, they lost Game 7.

"I just had to continue to pinch myself that I was actually now broadcasting a series with very similar ramifications and significance," Rose says. And now here he was, on that warm Friday, May 27, broadcasting from the radio booth that in those days was perched directly above the hallway the Rangers used to enter the ice. (It's better known as the tunnel from which hobbled Knicks center Willis Reed emerged before Game 7 of the 1970 NBA Finals.) Rose adored the location, which gave him a near-perfect view. By the end of the night, he'd need it.

Like thousands of other Rangers fans, Rose spent the end of Game 7 on tenterhooks. Zelepukin's goal was almost too much to take. "When you're less than 10 seconds away from the Stanley Cup final, the year when you win the President's Trophy, and people around the league think you're finally gonna break the curse and win the Cup, and you have that goal scored on you with 7.7 seconds remaining in the game ..." Rose says. "That to me constituted cruel and unusual punishment."

But as overtime began, his focus returned. By the time double overtime had arrived, he felt as if the Garden had been vacuum-sealed. "The entire world could be going berserk outside the building you're in and you wouldn't know it," he says. "You probably wouldn't care."

About four minutes into the second extra frame, Rose began narrating a play happening to his right, at the Eighth Avenue end of the Garden. From inside his team's zone, Devils defenseman Slava Fetisov fired a pass that hit New York forward Esa Tikkanen and ricocheted back into the corner. Before New Jersey blue liner Scott Niedermayer could retrieve it, Matteau swooped in. "My eyes were glued to the puck," Rose says, "I could see it on Matteau's blade as he carried it around the net."

Matteau shifted the puck from his forehand, then to his backhand, then to his forehand again. With the trailing Niedermayer hooking him, Matteau managed to free himself by swinging his body around so that his back was turned toward an ad on the boards. He finally had space, but remained hopelessly stuck behind the net. Drifting backward slightly, he somehow wrapped the puck around the near post. "I didn't aim at anything," he says now. "I would try that 100 times and I would score once." The shot hit Fetisov—who'd dropped to try to block it—then nicked Brodeur's blocker and slipped into the net. That instant, before most of the players had figured out what happened, Rose started shouting.

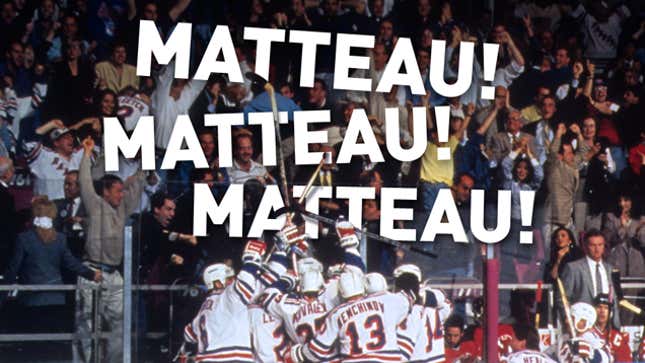

"He scores! Matteau! Matteau! Matteau! Stephane Matteau! And the Rangers have one more hill to climb, baby! But it's Mount Vancouver! The Rangers are headed to the finals!"

Matteau's goal at 4:24 in double overtime gave the Rangers a 2-1 victory. Rose's reaction was lucid, emphatic, and satisfyingly over-the-top. The scorer's name alone told the story, the way Rose let the second syllable of "Matteau" slip into his throat and roughen up a little, as if on the verge of coming apart altogether, the way he snapped off the full name —"Stéph! Ane! Matteau!"—in a ringing rhythmic foot, like the end of a toast. He even sneaked in New York's next opponent and his "One more hill to climb" line.

"What made Howie's call so great was the spontaneity and head-exploding joy of the moment," says Bruins play-by-play man Jack Edwards, who knows quite a bit about head-exploding joy. "He immediately captured the emotion of Rangers followers and inscribed one player's feat into our memories forever."

But seconds later, Rose started to worry. Color man Sal Messina openly wondered if Tikkanen, who'd crashed the net, had actually scored the goal. "I mean, can you imagine having the wrong guy after a call like that?" Rose says. "I'm going to have to run into a studio and start overdubbing, 'Tikkanen! Tikkanen! Tikkanen!'" Broadcasting from their booths up near the roof of the Garden, ESPN's Gary Thorne ("They score! They score! The Rangers have won the game! 1940 is history!"), MSG Network's Sam Rosen ("Score! Score! The Rangers win! The Rangers win!"), and the CBC's Bob Cole Chris Cuthbert ("Score!") all initially failed to identify Matteau as the goal scorer. But the radio guy had a better view than any of them. "I think that our broadcast vantage point made it possible for me to say with some certitude that it was Matteau's goal," he says. Watching the replay provided confirmation.

His facts were one thing, though. His emotions were another matter. During the postgame show on WFAN, Rose heard his call for the first time. He'd never come close to exploding like that on the air. Even if the outburst suited the moment, he was a little uncomfortable. He'd never sounded like such a rank homer. He remembered thinking, Oh, this is a little hysterical. Spitz, who also sat in the booth that night, recalls Rose approaching him after the game. "Spitzy," he said, "I think I blew it."

Spitz disagreed. He loved Rose's treatment. He likened it to the most famous radio call of them all: Russ Hodges's vivid description of Bobby Thomson's "Shot Heard 'Round the World" home run, the gold standard for off-the-cuff verbal grandeur. "The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!" is certainly the more famous of the two calls, but consider just how difficult a task Rose had. This wasn't Bobby Hull streaking down the wing, backing into the defense, and beating the goalie with a clean slapshot. Matteau's goal was a prayer of a play that developed in an instant. By the scorer's own admission, "It was a fluke."

At the time, however, Rose didn't think he'd done anything special. In fact, when he walked out of the Garden after Game 7, he felt defeated. His moment had come, and he'd butchered it. As he crossed 33rd Street, a man in his car yelled at him: "Howie, great call! Great call!" Rose assumed the admirer was simply caught up in the moment. But during his commute back to Long Island, he turned on WFAN and heard listeners and host Steve Somers gushing about the call. Rose found this both odd and uplifting. The Rangers had just notched their biggest win in 54 years, and fans were talking about him. "Yeah," Rose says, "I don't know that I needed my car to get home."

There are two kinds of great calls. There are the ones that capture the unfolding of a moment, that articulate what's happening on the screen with vivid and spontaneous precision ("He is moving like a tremendous machine!"). And there are the ones that capture the feeling of the moment, that find only enough words to remind you of their total inadequacy. A name, repeated in triplicate. What else is there to say?

Over the next 24 hours, Rose must've heard the call replayed on the radio 50 times. "I was just amazed by that," he says. Two weeks later, the Rangers climbed Mount Vancouver and won their first championship since 1940. After New York beat the Canucks 3-2 in Game 7 at the Garden, Rose drank from the Stanley Cup. During the summer, one of his two young daughters was photographed sitting in it. "Certain people have the perfect job," Spitz says. "Howie was a Ranger fan. He was that kid sitting up in the blue seats."

In the months following the Rangers' historic run, Matteau says, he didn't hear a single replay of Rose's call. The owners locked out the players in the fall, and without the internet or a cellphone, he lacked the resources to reminisce properly. When the season finally started in January, Matteau did pose for a few photos with Rose, although at first, the player swears, he had to be reminded of his connection to the broadcaster.

He doesn't need any reminders these days. Rose's call, Matteau says now, "was pure. You felt the 54-year drought. The pain, the joy."

Rose spent only one more season with the Rangers. Since 1995, he's been the Islanders' TV play-by-play man. These days, he also calls Mets games on WOR. But 20 years later, fans still approach Rose and scream: "Matteau! Matteau! Matteau!"

As for Matteau himself, after tallying six goals and three assists in the 1994 playoffs, he played another season and a half with the Rangers before the team traded him to the Blues. He retired in 2003 having never scored a goal as close in importance as the one he did in Game 7. Besides, how could he have?

In Montreal, where he lives, Matteau is rarely recognized. But when he's at a Rangers game at the Garden, fans serenade him constantly. "They're just happy to see me walking through," says Matteau, whose son Stefan recently was drafted … by the Devils. "I just keep walking and salute them."

Matteau and Rose talk every year, usually on the same day. Last May 27, as Rose prepared for that night's Mets game, he texted Matteau, who called back immediately. "They are linked forever," Spitz says.

"It's frankly a moment that you know a lot of broadcasters work their entire careers and never get an opportunity to have," says Rose. He's achieved the immortality peculiar to his trade: He'll be remembered forever for saying someone else's name. "I don't run from that at all. I've embraced it."

Alan Siegel is a writer in Washington, D.C. Contact him at [email protected]; follow him on Twitter @alansiegeldc.

Image by Jim Cooke; photo via Getty.