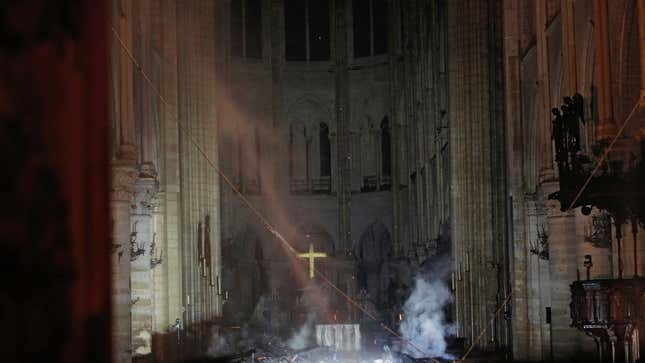

By now you’ve seen that Notre-Dame de Paris, the historic medieval cathedral in Paris, spent much of Monday being consumed by an uncontrolled inferno. Its stone body, which dates back centuries, appears largely to have survived the conflagration, as did the bulk of the religious relics and art within the cathedral. But the damage is a catastrophe nonetheless, because a fire can’t tear through a place as significant as Notre-Dame without doing knee-buckling damage to humanity. The torrent of videos of the fire devouring the cathedral’s roof and toppling its steeple, while Parisians could do nothing but watch helplessly, was enough to make you want to scream, or cry, or pull your head off. It was just what it looked like: a monument to our shared human heritage going down in flames.

As the old church burned, Osita Nwanevu of the New Yorker asked a good and also depressing question on Twitter:

I think the answer is close to zero.

Very few things built in recent years, and maybe none, will ever contain nearly as much history or beauty or meaning as a medieval cathedral or an ancient temple. Some of this is because they are not as old, but much of it is just because they are different; the kinds of hand-carved stone places of worship or memorial or monument that people and societies used to build, and now pretty much don’t, are just fundamentally unlike the things that people build now. What’s special and irreplaceable about Notre-Dame de Paris—or about Angkor Wat, or about St. Peter’s Basilica, or the Hypogeum of Ħal Saflieni, or any other members of their small class of buildings—isn’t just or even mostly that they’re very old, although it’s also no coincidence that these buildings got to be very old in the first place. They were built with eternity in mind, and are themselves both the manifestation and the record of the deeper devotion that called them into existence. The work of building them was a decades- or centuries-long collective act of prayer, by generations of people sharing a single wildly ambitious project. It was, from its conception, understood as something different and bigger than any other such endeavor. It wasn’t just a big church.

The cornerstone of Notre-Dame de Paris was laid in the year 1163; 87 years later, in 1250, its famous north rose window and western towers were completed. It underwent renovation and remodeling for years afterward, and has been wrecked or burnt and rebuilt a few times since. A cathedral of this sort is never quite finished, and that’s very near to the point of it, or as much a part of the broader point as beginning the work in the first place. In any event, in the 12th century some stonemason began working on a section of Notre-Dame de Paris knowing, as a matter of absolute fact, that he would not live to see the completion even of his own part of the broader project. And yet he took that job believing that, if he worked well and his work pleased God, maybe his great-grandkid would be there to complete it. On the far side of the project, another craftsperson made this choice, and another.

The end result has to last forever to make good on that faith. It has to be timeless and eternal and therefore outside time, so that the communion it hosts can include you there in the pew in 2019 as well as the artisan who sculpted that part of that arch over there 800 years ago; so much has to go right so that both of you can be present at, for example, the Last Supper, and so that all the prayers of everyone who ever has or will ever participate in that communion can be swept up into one sound, all calling out together from atop their speck of dust. In a building like this, everything you see is some once-living human’s life’s work—the articulation of somebody’s faith, somebody’s high soaring ambition to consecrate into permanence his love of beauty and devotion to a craft. You see it in the lovely and lovingly shaped curve of stone in a random sector of rib vault suspended dozens of feet above the top of some checked-out tourist’s head. Some other person’s life is legible in the fine, ornate metalworking around the altar. You could go to Mass every weekend for a lifetime and never particularly notice any of it, but it is written on every inch.

This is not how buildings go up in modern times, and not only or even mainly because technology and construction methods allow them to go up much faster than they did in the 12th century. The project, in constructing a medieval cathedral, was not to get the building up and completed and into use as quickly or efficiently as possible, so that the developer could begin charging rent on its interior square footage. The project was to make the most beautiful and most awe-inspiring possible work of devotion, to create the most permanent possible monument to the human ideals that inspired the project. The idea was to do this no matter how long it all took—to make the finished product vast and timeless and cumulative; such a building would invariably be filled with mystery, would hum with it, and would be worth tending and nurturing and loving forever.

Somebody’s vanity is in there, sure: The king or potentate or bishop or nobleman or whatever rich guy ordered the thing be built, sure. But that passing human ambition would, if it all worked, be engulfed and subsumed by the commitment of the people who did the actual work of making the building, and then again by the awe steeped into the stones by centuries of people who stood there and looked up and felt themselves in the presence of something vast and incomprehensible—maybe God or maybe the no-less-mysterious transubstantiation of all those individuated labors, over generations, into this unified thing. The building is the result, but it’s also a proof—a stone and wood and glass and plaster record of its own creation and meaning, a realization of that first baffling aspiration to make something worthy of containing the infinite.

I think it’s a bare statement of fact and not a curmudgeonly gripe to say that that’s simply not how a building—even a church, even a cathedral—gets built in this capitalist post-industrial world. A lot opens up in a city; nobody with the authority to do anything whatsoever bothers to ask, “How can generations of artisans and craftspersons and laborers work to erect a monument to the eternal in this place, the beauty and timelessness of which will overwhelm people and fill them with awe and make them feel that they are in the presence of the divine from now until the end of time?” That’s not practical, and it’s also not the scale on which anything happens anymore. Instead, a real estate developer—Donald Trump’s class of person, that is—buys it, and asks, “How soon can I get a sleek, efficient steel-and-glass container up into this lot and start making money off it?”

And that’s fine, mostly. Not every or even most buildings can be hand-made everlasting temples to the divine that take longer than an average human lifespan to construct, or it would be quite a bit harder to shop for a new pair of shoes. Probably there are good reasons to prefer society not apportion 87 years to the construction of fantastically ornate cathedrals anymore. But Hudson Yards and Jerryworld and the friggin’ Gherkin will not be standing 800 years from now. They weren’t meant to.

And even if they are standing, somehow, they will not be repositories of art and history and faith on the scale of Notre-Dame de Paris. They weren’t meant to be that, either. They’ll just be relics showing what buildings were like a long time ago, because they weren’t built with anything else in mind. They were only ever just buildings, modular and functional, in part and in whole meant to be replaced when they break. They only ever get old.